Expect nothing and you won’t be disappointed. This is the mantra of the pessimist and the persecuted alike, the preemptive strike of those who tend to paint the picture a little blacker than it is. And then there is Joan Rivers, the orneriest creature ever to darken Hollywood’s door. She once told me that her husband, Edgar Rosenberg, who killed himself in 1987, lived by the heartwarming motto “Fuck them over before they fuck you over first.”

I have known Rivers for 22 years, long enough to know that she does not exactly share this view of the world, even if she likes to muck around in it from time to time. In fact, she considers it a flaw in her late husband’s character, one that set in motion the chain reaction that almost destroyed her career: In the mid-eighties, Rivers was one of the most successful comedians in the world. She was the highest-paid entertainer on the Vegas Strip and Johnny Carson’s permanent guest host on the Tonight Show, until she was lured away to Fox to host her own late-night talk show. Edgar, she says, was a toxic presence on the set of her show, fighting bitterly with Barry Diller and Rupert Murdoch over everything from office furniture to money. Joan and Edgar were fired after only seven months, and the fallout was devastating. She was excommunicated by Carson, her mentor, for leaving; she was effectively banned from late night, hardly ever invited to appear on Letterman, Leno, Conan. Her marriage fell apart and then Edgar swallowed a bottle of pills. Her daughter, Melissa, stopped speaking to her. Rivers fell into a deep depression, became bulimic, and considered suicide herself.

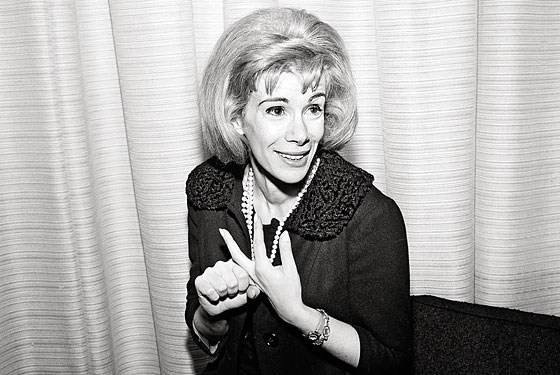

When I first met Rivers it was 1988, just a year after Edgar had killed himself. She was moving back to New York after fourteen years in Los Angeles and taking over Linda Lavin’s role in Broadway Bound, a gig that she says pulled her life out of its nosedive. It wouldn’t be the last time she found redemption through her work.

On a recent morning in early May, we are sitting in her study eating cake. It has been served to us by Kevin and Debbie, her butler and housekeeper, who have been living with her for twenty years in their own quarters in her grand apartment, a mini-Versailles on East 62nd Street. (“Marie Antoinette would have lived here,” Rivers likes to say, “if she had money.”) Joan loves cake, loves anything sweet. The Joan Rivers diet: You can eat anything you want before 3 p.m. and then nothing for the rest of the day. When she goes out to dinner, she puts a small pile of Altoids on the table next to her plate, which she eats one after another while barely touching her food.

We are talking about the peculiar turn of events her life has taken recently, how she is suddenly squarely at the center of the culture again—something that has escaped her since her Fox debacle. At the age of 76, it seems, she has been rediscovered. Much of it has to do with a new documentary about her life, Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work, which opens in theaters on June 11. Roger Ebert wrote, in one of the film’s many rave reviews, that it is “one of the most truthful documentaries about show business I’ve seen. Also maybe the funniest.” The film comes at the end of a remarkable year for Rivers, one that began when she won The Celebrity Apprentice (after one of the uglier reality-TV showdowns), outfoxing all those bimbos, has-beens, and two-bit poker players to emerge—somehow—as the sympathetic character. At long last, not fired! It’s unfamiliar territory for Rivers: to be the one people root for.

“It’s amazing,” says Rivers, shaking her head in disbelief. But then this: “People who have seen the film come up to me and say, ‘I never liked you until now.’ TV interviewers say, right in front of me, ‘Even if you have always hated Joan Rivers … you are going to love her and be mesmerized by this film.’ They spit right in my face and then spend the next ten minutes wiping it dry.” That is when she shows me the pillow she has embroidered that sits on a leather couch in her study: DON’T EXPECT PRAISE WITHOUT ENVY UNTIL YOU ARE DEAD.

If Joan Rivers has a hard time taking a compliment, she has an even tougher time handing one out. “I will only praise someone who can’t take anything away from me,” she says with a mordant laugh. “People ask me all the time: ‘What do you think about Sarah Silverman?’ ” She switches into a comically polite-insincere voice. “Hmmm. She’s nice, I guess. I really haven’t seen her.”

She shoots me a get-real look. “She’s terrific. She’s very funny and very pretty. But why should I admit it?”

Even at this late stage in her 40-year career, Rivers is nowhere near ready to cede the stage to a younger generation. (As her former manager Billy Sammeth says in the film, “Right now they see her as a plastic-surgery freak who’s past her sell-by date … But God help the next queen of comedy, because this one’s not abdicating. Never will.”) I am reminded of an e-mail she sent me a couple of years ago, when she was at yet another low point in her career. I asked her what she thought of Kathy Griffin. “I am her friend but also furious,” she wrote. “She is the big one now. My club dates have simply vanished and gone to her. She will last as she is very driven. Like me, she wants it. But every time a gay man tells me, ‘Oh, she is just like you! I love her!’ I fucking want to strangle them. But, please God let someone give me credit. I feel so totally forgotten. The fucking New Yorker did this big piece on the genius of Rickles, who is brilliant but who hasn’t changed a line in fifteen years. Meanwhile, I am totally ‘old hat’ and ignored while in reality I could still wipe the floor with both Kathy and Sarah. Anyhow, fuck them all. Age sucks. It’s the final mountain.”

In late January, Rivers made her first trip to the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, to attend the premiere of A Piece of Work. Directed by Ricki Stern with Annie Sundberg, whose previous two documentaries were about wrongful convictions and Darfur (go figure), the film is essentially a year in the life of Rivers, who comes across as, if not the hardest-working person in show business, then certainly its most unrelenting practitioner. Ricki Stern is the daughter of her friends Marjorie and Michael Stern, a couple Rivers met five years ago “at a stuffy dinner party” in Connecticut, where she has a country home. “Marjorie was the only person who laughed out loud when someone said Demi Moore was talented,” jokes Rivers.

At Sundance, Rivers wears a slight variation of the same all-black outfit every day. Today: Donna Karan sweater, Chanel slacks, Manolo boots, full-length sable fur, huge sunglasses. Among the green and crunchy in their polar fleece and turquoise jewelry, she stands out like a whore in church. She knows she is anathema to this crowd, with her ostentatious plastic surgery, conservative streak, and glitzy lifestyle. Though she calls herself an independent and voted for Obama, she is constitutionally Republican. Friends with Nancy Reagan. Thinks we should just bomb the shit out of Iran. Ambivalent about feminism. Detests whining and victimhood and laziness. Hated Precious. “I got very annoyed,” she says. “I thought, Oh, get a job! Stand up and get a job!”

To Rivers, Sundance is a tribal gathering of the too earnest and the no fun—artistes in hypocritically expensive jeans. At one point, she sits down for an interview with the film critic Peter Travers and he asks her about her first trip to the festival. “Everyone here is an act-or,” she says. “ ‘Hi, I’m Deborah, and I am an act-or.’ Oh, fuck you. You are an actress.” Who’s funny to you? he asks. “At Sundance? I find no one funny.” She cracks up. Are you going to be serious while you’re here? he asks. “When I meet Bob Redford I will be serious,” she says. “If I recognize him after the face-lift.”

She travels around town in a black Escalade bursting with entourage: two assistants, Jocelyn and Graham, hair-and-makeup man Martyn and his boyfriend Digby, as well as Marjorie and Michael Stern. It is a rolling cackle-fest, Rivers slaying the group with metronomic consistency. She is a spoken-word Twitter feed, constantly streaming one-liners: sometimes shocking, sometimes vile, sometimes cruel, always hilarious. Not surprisingly, she is recognized everywhere she goes. As we are heading into a restaurant on Main Street for lunch one day, she is swarmed by a group of very young people with pierced lips and pink hair. Rivers, as a young film-industry guy tells me one night at a party, is considered cool to people too young to know her as anything but the outrageous red-carpet lady. As we head into the restaurant, the strangest-looking chick in the group yells, “I love you, Joan!”

A few weeks before Sundance, I called Rivers to ask about the documentary and I got hit with her don’t-expect-anything-and-you-won’t-be-disappointed voodoo. Asked about Ricki and Annie, she cracked, “They don’t wear makeup.” Do you like the movie? Long pause. “They forgot to show that I actually enjoy my life.”

But now, in Utah, it is finally sinking in that the movie is good. The premiere is at a synagogue, funnily enough, and after a long wait in a makeshift greenroom there is a silly press conference and photo op, where Rivers, off the top of her head, makes the joke, since repeated, that she should have made a documentary about her life selling jewelry on QVC called Semi-Precious.

Rivers seems nervous on her way in to the theater. It is the first time she is seeing the film on a big screen in front of an audience. As we wait for it to start, she tells me a story about Prince Charles, with whom she has been friends for several years. (“Not inner circle,” she says. “Outer-inner circle.”) HRH sends her a Christmas gift every year, which, more than once, has been two very fancy teacups. “One year,” she says, “I took a picture under my Christmas tree with the teacups and wrote, ‘How could you send me two teacups when I’m alone?’ Another time I wrote, ‘I’m enjoying tea with my best friend!’ and I sent a picture of me in a cemetery. And he never acknowledges it! He never says to me when I see him”—doing his accent perfectly—“ ‘Ohhhh, funny funny funny!’ So this year I thought, I’m just going to write him a nice thank-you note. And the other day our mutual friend calls and says, ‘Just spoke to Charles! He said, “I can’t wait to see Joan’s note this year!” ’ ”

As the theater fills up, a steady stream of fans and well-wishers stop to chat. A woman in the aisle in front of us turns around and asks, “Doesn’t that bother you?” Rivers says, “Are you kidding? Forty years! Thank God they’re still doing it. I have many friends in the business they don’t bother with anymore, who are asked to step aside on the red carpet, and that’s more embarrassing.”

Rivers has always got her nose in a book. She devours them, several at a time. On this trip, there is Game Change. “Hillary comes off as furious and rightfully so. And you hate Obama in the end. He’s weak. Michelle is the tough one. Palin is a moron. McCain is an egocentric fool.” The other she is reading is George Carlin’s Last Words. “It reminds me why I hated him,” she says. “The arrogance, the self-congratulatory tone, the superior attitude, and then the selling out for any shitty award.”

It is a cliché but it is true. Most comedians are dreary bores: neurotic, self-obsessed, competitive, and no fun when they are not onstage. Not Joanie! She is funny in the way that your funniest friend is: aware of everything, well-read, opinionated. She also asks good questions. “Who do you hate?” is one of her conversation starters, and it always works because there is always someone to hate. At the moment, she hates Oprah, who she thinks is phony. “How can I help out Kitty Kelley,” she says. “Should I throw her a book party?”

Her single greatest gift is her ability, in the heat of the moment, to find the funny line. My recent favorite example also highlights the rarefied world in which Rivers sometimes travels. Not long ago she was invited to dinner at Lily Safra’s home at 820 Fifth Avenue. Safra owns the most expensive residence in the world, the $500 million Villa Leopolda in the south of France. Rivers was seated next to Carroll Petrie, a rich society lady who is deaf as a post, and the two of them were marveling over, oh, I don’t know, the dozens of Fabergé clocks in Safra’s house. Petrie said, too loud, “Doesn’t it just make you feel poor?” To which Rivers replied, “Carroll, name me one other person in this room who is playing Cleveland this weekend.”

One of the most consistently subversive things about Rivers is her level of commitment to a spur-of-the-moment prank. I have seen her pull off dozens of them over the years. Once, coming out of Pat Wexler’s office, where she goes for her Botox and filler, she crawled on her hands and knees into a waiting room full of socialites and models and, screwing up her face to resemble a stroke victim, moaned out of one side of her mouth, “Look what she did to me!” Another time, she played a practical joke on Marjorie Stern and some unsuspecting diners at Sarabeth’s: “It’s like three weeks into the Bernie Madoff thing,” says Rivers. “I get there first, and there are two tables to pass before you get to our table. And one was like six Jewish ladies and the other was two Jewish couples. You could just tell. Very New York people. I grabbed the waitress and I say, ‘Please don’t say her name, because Mrs. Madoff doesn’t want people to know it’s her.’ I said it loud enough for the other tables to overhear it.” Marjorie, who has a Ruth Madoff aspect, takes the story from here. “I walk in and they are all staring at me. And I look over at Joan to see what the problem is and she says, ‘Ruthie! Sit here!’ At which point the entire place is stunned speechless. Forks suspended in midair.”

“They hissed at her,” says Rivers, crippled with laughter. When I remind her that there are six Jewish ladies who now think she is friends with Ruth Madoff, she yells, “I know!” and laughs even harder.

Rivers will take the piss out of anything. Shortly after I had lost a big job, she called, and when I answered the phone a bit too quickly she said, “Really? The first ring? So desperate.” And then she hung up on me. A few days after 9/11, she called and asked me if I wanted to meet her for lunch at Windows on the Ground. She pushes as far as she can as soon as she can. It’s compulsive.

In the film there is a scene where Rivers is playing some lousy casino in Wisconsin, and she does a bit about Helen Keller and a man stands and bellows, “It’s not very funny if you have a deaf son!” Rivers lets him have it. “Oh, you stupid ass, let me tell you what comedy is about … ”

“You go ahead and tell me what,” he says.

“Oh, please,” she says. “You are so stupid. Comedy is to make everybody laugh at everything, and deal with things, you idiot.”

At Sundance, an interviewer asks her about the moment. “If you laugh at it, you can deal with it, and if you don’t, you can’t deal with it. And don’t start telling me that I shouldn’t be saying it. That’s the way I do it. I would have been laughing at Auschwitz.”

One of the great misconceptions about Rivers is that she is mean-spirited and heartless—that there is nothing more to her than her comedy or her red-carpet patter. To the celebrities who are on the receiving end of some of her sharpest material she can seem cruel, but as a civilian she is surprisingly sensitive, someone who cries as easily as she laughs. At Sundance alone, she is brought to tears a half-dozen times. A journalist interviewing her on camera asks if she could sing a few bars of the song that’s been in her head lately. She demurs for a moment, saying she can’t sing, and then chokes out, in that raspy voice of hers, a few lines from “Send in the Clowns” (“Isn’t it rich / Isn’t it queer … ”). When she starts to cry, the guy asks her why. “Because that’s life. And I’m very tired. Life is very tough. If you don’t laugh, it’s tough. And ‘Send in the Clowns’ is a song that says you need that because it’s all … ” She chokes up again and then says, “Horrible.”

One day at Sundance while we are waiting for a screening to end, Rivers is approached by an older gentleman. “Excuse me,” he says. “I just have to interrupt.” Rivers looks up at him and cautiously smiles. “I want to thank you for bringing me joy in 1960 in Korea.” Her body language changes in an instant. “I was a gay soldier in peacetime Korea who was starved for Broadway,” he continues, “and you were performing with the USO troop.” He pauses to watch the memory dawn on Rivers’s face.

“Sheila … ”

“Sheila Smith! Yes!” says Rivers, stunned.

“Jack … ”

“Jack Edelman! Yes! Yes! Yes!”

“Patience Cleveland,” he says.

Rivers screams, “Patience Cleveland!”

“Richard Nealon.”

“And Jeanne … Jeanne Beauvais,” says Rivers. “The opera singer … How do you remember the names?”

“I was way up above the 38th Parallel in Camp Kaiser, Korea, and will never ever forget all of you.”

“That was my first traveling job that paid,” says Rivers.

“She was an ingenue. A young singer-comedienne. Light comedy,” says the man to Rivers’s entourage, who are hanging on his every word.

When the man leaves, Joan says, “We were on the DMZ line between North and South Korea. It was very scary but it was fabulous. Patience Cleveland was pregnant and was trying to have an abortion. We took hot sea baths in Japan. We got these two crazy marines to ride us over bumpy terrain in Korea. Nothing worked. And she went back to New York, went to a Chinese restaurant on West 46th Street and went down into the basement and got an abortion.”

Michael Stern says, “A Chinese restaurant? Did they do it with MSG?”

Rivers pauses for a nanosecond—wait for it—and finds the line. “Bite down on this egg roll.”

What strikes me as this scene unfolds is just how long Rivers has been this radically modern presence. One of the best things about the documentary is that it reminds you, with great archival footage of Rivers’s early TV performances, that she is the mother of a certain brand of transgressive female comedy. Would there be a Sandra Bernhard or a Roseanne or a Rosie O’Donnell or a Kathy Griffin or a Sarah Silverman, without Joan Rivers? “When I am onstage, I am every woman’s outrage about where they put us,” she says to me one day. “We have no control. And that’s why I am screaming onstage. We have no control! I am furious about everything. All that anger and madness comes out onstage.”

Rivers adored her mother. “She died in my mid-to-late forties,” she says. “She was so smart and funny. My friend Alice told me at her funeral that my mother once said to her, so proudly, ‘Joan isn’t just a star. She’s a superstar! And she did it all herself!’ It still makes me cry. Both of my parents got to see me host Carson, thank God. That’s all anyone wants: to have their parents see they’re going to be all right in life.”

Her relationship with her own daughter, however, has not gone as smoothly. Some of the more visceral scenes in the documentary are between Joan and Melissa. There is something in their body language, in the way they talk over each other, that gives you a glimpse into the dynamic: classic yenta behavior on Joan’s part; stuck in a sullen teenage gear on Melissa’s part.

Someone who knows both women well said to me recently, “The greatest thing about Joan is her bravado, her ability to just laugh at everything and push through. But her greatest weakness is that moment when she can’t push through and she really takes something in. She can become unreasonable and vindictive. And it usually has to do with Melissa, when she feels that Melissa has been wronged. When Melissa has an enemy it has to be Joan’s enemy. But Joan carries it to the level of a crusade.”

I ask Melissa if she thinks her mother is still reacting out of guilt over that terrible time in their lives. “I think she does have a lot of unresolved guilt.” But, she says, “as an adult I have such a clearer perspective and acceptance of who my mother is and why she does what she does.” She also concedes that she has plenty of baggage of her own. “I carry the burden of my father, in his note, saying to me, ‘You have to take care of your mother.’ I take that very, very seriously. I feel like she is my responsibility.” She pauses for a moment. “And yet! I feel like we have a really good relationship. And it’s very normal in abnormal circumstances.”

“All I want you to do, if we are sitting down and it’s after 6 p.m., is tell me the truth … Just tell me the truth and let me say to you, ‘Things are lousy and I’m sad.’ ”

Melissa was worried at first about the documentary. “Melissa is a very private person,” Joan says. “And she doesn’t understand show business. I will do anything on camera. You want me to do what?!?! … Hmmm. How much? … Okay!” When Ricki Stern showed Rivers a rough cut, she sent back three pages of notes. Most of her complaints were about what was not in the film: Where’s the red carpet? Nothing on QVC? You don’t show my triumph in Edinburgh! “And then there were certain things that you really shouldn’t put in, that Melissa objected to,” she says. “I talked about Edgar one night and it was very late and I was saying what I say very often, which is that I walk past his picture and give him the finger. Fuck you, what you did to us! Which is part of suicide. But it shouldn’t maybe be there. Melissa didn’t want to see that.”

But Melissa seems to be coming around: “The first time I saw the film it was very difficult to watch. She is showing parts of herself that I see and I understand and I was worried that other people wouldn’t understand. But from the response the film is getting, I think I was wrong. Because people do understand.”

This summer, the family begins filming a reality show for WE called Mother Knows Best. Rivers has rented out her house in Connecticut for the season and is moving in with Melissa and her 9-year-old son, Cooper, whom Joan is crazy about. “He is funny,” she says, handing out her highest praise. “And he gets that I’m funny. He recently told me that he knew that I was famous. And I said to him, ‘You know why Grandma is famous? Because I make people happy.’ ”

Rivers says she is nervous about the show. “I don’t know if it’s going to wreck our lives. I think it’s going to be very hard on us because I don’t want it to be one of these stupid reality shows. We want it real, with real mother-daughter conflict and real problems.” Like what? “I want her to get married to the boyfriend and they don’t want to get married. I’m sorry, I am not comfortable with somebody coming down the stairs in his jockey shorts who is not married to her.”

Melissa responds: “She’s, like, completely supportive of gay rights and everyone should be able to do whatever they want, live and let live, and whatever makes you happy. She has no problem with, like a rhino and a ferret living together, and yet she can’t believe that I don’t want to get married again!”

There will be plenty of grist for argument. “Everything she does in the house gets me crazy,” says Rivers of her daughter. “The way she lives—very California. Have a sandwich over the sink? Excuse me?”

The way that Rivers lives is very old-fashioned and extremely formal, with her live-in butler and stiff dinner parties with finger bowls. “It comes from the way my mother was raised,” she says. “She came from very rich Russians who had servants. When they came here they were dead broke, but my mother remembered that from childhood. She always lived very formally, or tried to.” I tell her that people are surprised when they see the film by how grandly she lives—this foulmouthed comic in her gilded palace. “This business is such a mess. Nothing is set in stone. As I say in the movie, ‘You are standing on mud.’ So the formality, the rigidness of sitting down to a beautiful table, it’s a ritual. My bed is turned down every night. But that’s because I’ve just come from hearing someone say, ‘If you’ve always hated Joan Rivers … !’ I want things to look pretty. I should have been Martha Stewart. Martha Stewartvitz.”

Earlier this year, apropos of nothing, Rivers sent me an e-mail while she was out in L.A. visiting her daughter. “Just bought Melissa three hundred dollars’ worth of new place mats. God she must hate me.”

“That is a perfect example of what our relationship is like,” says Melissa. “So, my place mats are a little worn out! We all get busy. But my mother had the car stop on the way from the airport to my house. And showed up with all sorts of new place mats and napkins. Without asking me. That’s stepping over the line a little. I can’t take care of myself?” She laughs. “But luckily I needed the place mats.”

All this talk of proper homemaking reminds me of something Rivers said to me years ago. She was talking about the scene in one of her favorite movies, Rebecca, when Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine realize that their relationship is not what they thought it was. “Bad things can happen,” said Rivers, “even in a pretty house.” When I mention this to her now she says, “Sure did on Ambazac Way”—where they lived in L.A. “We were in Architectural Digest.” Pause. “Edgar still jumped.”

Joan Rivers will turn 77 on June 8. “Age is so frustrating,” she says to me in her study in New York. “I make deals with God all the time. ‘Give me ten more good years and I’ll call it a day.’ Age is the one thing that is absolutely coming at you. And right now, thank God, everything is working. I have my checkups and the doctors always say, ‘I can’t get over it!’ But I am pedaling as fast as I can. My manager was just here today. He said, ‘There’s very little left, timewise.’ But I can do it! I can do a radio show from anywhere! I just have to keep the pot churning. You cannot stop.”

People always ask Rivers why she doesn’t just retire, enjoy her old age. “But they don’t get that I love it,” she says. “All I ever wanted was this. I’m lucky, you idiots.” Here, she imitates her society-lady friends. “ ‘We’re going to the Kentucky Derby and then taking cooking lessons in Venice and then we are going on so-and-so’s boat and then perhaps five fun days with a group to the Galápagos!’ And you go, Why? I’ve done all that crap. That’s not retirement to me. That’s death.”

When I ask her how she fell in with that crowd, she says, “Sort of by mistake. I got friendly with C. Z. Guest and through her I met Jerry Zipkin and I had no idea that if Jerry and C.Z. said, ‘This Jew is okay,’ you were okay. You got in. Immediately. And it’s all very glamorous at the beginning. Going to the Metropolitan Opera, taking a table here, being on a committee there. Going out all the time all dressed up.”

She levels me with a look. “And then I got bored to death. Nobody tells you the truth. I once asked one of the ladies, ‘Did you ever have an affair?’ And she stared at me like I was crazy. ‘Why would I tell you?’ she said. Another time, someone had just bought an apartment and I said, ‘How much?’ And she said, ‘That is really none of your business.’ And I thought, Fine. Then we are not friends and I don’t want to spend any more time with you. I was friendly with one couple who I no longer see at all. They would always say, ‘We’re such good friends.’ And then I found out that their daughter had a complete nervous breakdown. For a year, I was always told everything is wonderful. Well, then what are we wasting our time here at Elaine’s or Mortimer’s or Swifty’s? I don’t want to sit in Swifty’s and not say anything about anything. I just totally stepped away. Blaine Trump is one of the few people I am friends with out of that period. She’s honest. She will sit there and say, ‘Life is crap.’ All I want you to do, if we are sitting down and it’s after 6 p.m., is tell me the truth. Because we’ve all lied to each other all day long in business and we’ve all had these lunches and we’ve all ass-kissed to the point where I carry Chapstick. If I am going to sit down and eat with you, just tell me the truth and let me say to you, ‘Things are lousy and I’m sad.’ ”

One of the saddest times in Rivers’s life since I have known her was when her best friend Tommy Corcoran died a few years ago. Rivers spoke to him three times a day and he walked Melissa down the aisle at her wedding. When I ask her about the challenges of getting old she says, “The loss of friends. It’s the thinning out of people with whom you have a history, whom you adore. I feel amazing. I truly feel like I am 25. I walk everywhere. There’s nothing wrong with me. The mind is going better than ever. But I look at my living room at night and I see Tommy and the good times and that just really upsets me. There’s no one to call up. Nobody cares that you got home. That’s horrible. To go into your apartment and nobody cares that you came off the plane very late. And suddenly you develop tremendous attachments to your dogs. And then you know that it’s sick. They are animals and they love me, but it isn’t right to say, ‘My dogs! I’ve got to rush home to the dogs!’ They’ll be just fine without me.” There is a long silence as she looks up to keep the tears from ruining her makeup. “And the other thing with age is that you have no tolerance. You just think, Ugh, don’t. I’ve played this game. You just want to say to people, ‘I’ve been through it.’ ”

After the first day at Sundance, Rivers insists that I move out of my fleabag hotel and into a giant suite that is connected to her giant suite at the Stein Eriksen Lodge. “It’s already paid for,” she says, “and I will only use it to put on hair and makeup.” And so we become roommates for a couple of days.

When we get home at night, and she closes the door between our suites, I can tell she is staying up late. “My day starts when I get home and it’s finally over,” she says. “I take my bath and do my crossword. I call it puttering. I may read a book. I go through The Wall Street Journal, I watch television. I want two and a half hours with no one talking. I went to bed at 4 a.m. last night. I do that every night.”

In the morning, Rivers comes in wearing her nightgown and no makeup, and she and Martyn begin the lengthy beautification routine. At one point in the film, as Rivers is sitting in a chair getting made up for some event, she says to the camera, “It’s very scary when you see yourself totally without any makeup … Oh, it gives me the willies. Who is that person? So, I get up in the morning and the first thing I do is I get into makeup. I was never the natural beauty. No man has ever, ever told me I’m beautiful.” The insecurity is touching, and perhaps a clue as to why she has availed herself of so much plastic surgery over the years.

Rivers has had three big relationships since Edgar. “Spiros was my first one, my Greek shipping tycoon. That lasted four years.” Then there was Bernard, the cheap one. “He wouldn’t get a car and driver. A man who had $150 million. I was standing there in the pouring rain at Lincoln Center and he said to me, ‘You are so spoiled.’ I remember saying to him, ‘If you were an actor, Bernard, and had no money, we would be on the subway and I wouldn’t be saying a word. But you have $150 million, Bernard. And I’m wearing $700 shoes, and this is silly. What are we proving here?’ Bernard carried the ketchup back and forth to the Hamptons. Does that tell you everything?”

And then there was Orin Lehman, of the Lehman Brothers family, who served as New York State’s parks commissioner. He was a World War II hero who was injured in the Battle of the Bulge and had the use of only one leg and walked with metal braces. Rivers was with him for nine years, until she caught him cheating, in 2001, and threw him out. “I was mad about Orin,” she says. “Love of my life. Adored him. People would say, ‘Orin Lehman? Blech.’ Melissa never got what I liked about him. But he was amazing. A gentleman. He was elegant. He got everything. He was so brave. I loved the bravery. That this man walked. He willed himself to walk. I know it sounds strange, but he was very sexy.”

I ask her if she still hopes to meet someone. “Yes, but it’s very hard at this age. The pickings are so slim. I’d love to have somebody. And my terms are: Pay every bill I have and you’ve got to understand that I love my life and I love the theater. Talk about set in your ways. I love what I do, I love how I do it. I have my country house, I have my family, and I have my career. Where are you going to fit in? Call me a week from Tuesday.”

There is one man in particular she’s interested in. “He’s coming in February. He’s taking me to the dog show.” She laughs.

“Very, very rich,” says Marjorie.

“He’s from Oklahoma City,” says Rivers. “So it’s over already.”

And then she takes it a step further, paints the picture a little darker. “He’s a man in his seventies and he’s going to meet a very beautiful young woman in her fifties who will move in so fast, and he will feel so good, and she will show him a picture of her twat and it’s finished.”

Later that day, after a packed screening at the festival (“Listen to them laugh,” Rivers had said backstage, her eyes lit with joy), Rivers comes into my room and her mood has changed. “This is why everything sucks,” she says. “At the end of the day, no such thing as, ‘Ain’t it going great?’ We came here, we’re the toast of Sundance, Melissa calls me up beyond happy” about the good reviews for her new book about lessons learned on the red carpet. “The next call is from this man, who I have had dinner with three or four times and really clicked with. He asked me to save the week of February 14 because he’s coming in. Now he says, ‘Coming with a lady I’ve met that I know you will love as much as I do. Can’t wait to spend the week with you!’ My God. How about that? Nothing is ever a hundred percent. There’s no such thing as ‘everything is going great.’ ”

On the last night in Utah, Rivers and her entourage are going to dinner at an Italian restaurant to celebrate her assistant Jocelyn’s birthday. The snow is really coming down, so Jocelyn decides we ought to take the shuttle bus into town. Too dangerous to drive. “The diva is going out in style,” she says to her boss. “You can overrule us, but we all feel it’s the safest way.” We arrive at the restaurant and Rivers immediately begins to kvetch and worry about where we are going to be seated. But as soon as we settle at the table—a big round corner table with a beautiful view of the snow falling on the side of the mountain—her mood lifts. She ignores her mints and actually eats her dinner. She also knocks back a couple of glasses of red wine and before long is on a serious roll, telling funny stories and teasing the waitress (“You are never going to meet a man with that butch haircut”).

As we await the arrival of the birthday cake, Rivers launches into a story about a night in the early nineties when she performed at a big star-studded televised Comedy Central event at Radio City Music Hall. What I remember most about that night is how great she looked, how nervous she was in the limo as she ran her lines, and how she roared through her set and the audience went nuts. I have never once heard her brag about a performance. But now, at dinner, she is telling the group, “I walked in there and killed.” The disappointing part was what happened next. “They wanted to do, like, an original-cast moment. They wanted to put me up there with the Greats and the Has-Beens, you know what I’m telling you? I thought, What don’t you understand here? Don’t you put me out there with Phyllis Diller and Milton Berle. I was so angry that I wouldn’t stay for the finale. Into the limo!” She pauses. “But that night was a big night in my life.” And then she says, more quietly, “I was at such a low point then. And they were all coming over to me, all these comediennes, and each one has their own little show and I don’t. And they were all”—mockingly—“ ‘Thank you, Joan. I wouldn’t be where I am but for yoooou.’ ” She takes a big gulp of her wine. “You want to say to them, ‘I will show you how it’s done, pussycat. Follow that.’ ”