Please don’t flash your nostrils at the camera,” Kal Penn’s publicist tells him, as if she’s said this countless times before. “What?” Penn says, grinning. “They said to act like I’m looking in the mirror in the morning. You’ve got to check for snot.”

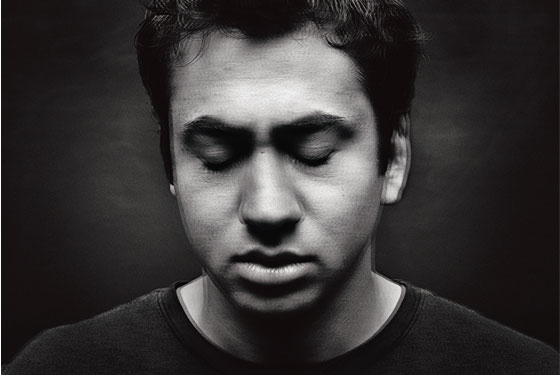

It’s a sleepy Sunday afternoon, and we’ve gathered in a photo studio nine stories above Noho to help document Penn’s graduation from (admittedly awesome) stoner flicks like Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle to a more serious sort of cinema. In a few days, he will open The Namesake—an independently financed labor of love by Mira Nair, based on the novel by Pulitzer Prize winner Jhumpa Lahiri, in which Penn plays Gogol Ganguli, the American-born son of Indian immigrants struggling against his parents’ traditionalism. The movie also happens to be the only notable item on Penn’s résumé that doesn’t feature exploding diarrhea, engorged dog testicles, or Neil Patrick Harris snorting coke off a stripper’s ass. (Asked if she’d seen any of his oeuvre, Nair laughed: “No! I can’t. I can’t!”) A suitably reflective shot will emerge from this photo session, yet in the meantime, here is Penn—loose, laughing, and churning out frames that look as if he’s just happened upon the world’s biggest bag of pot. Maybe he’s just a jovial guy. But somehow all the hamming comes across as an acknowledgment that turning his back on the dude movies that made him the most successful Indian-American actor of his generation isn’t going to be easy.

“Yeah, the majority of roles I get offered are very stereotypical. Look at the movies I started off doing, like [National Lampoon’s] Van Wilder,” Penn says of his breakthrough role as Taj Mahal Badalandabad, an Indian exchange student whose only desire is to study “the great American art of muff diving.” He’s shooting a Kumar sequel right now, and as for his recent stint as a terrorist on 24, he admits, “I have a huge political problem with the role. It was essentially accepting a form of racial profiling. I think it’s repulsive. But it was the first time I had a chance to blow stuff up and take a family hostage. As an actor, why shouldn’t I have that opportunity? Because I’m brown and I should be scared about the connection between media images and people’s thought processes?”

Black actors, of course, have had similarly legitimate complaints and concerns for the past 80 years. But for Penn, 29, the problem is slightly different—his is the only instantly recognizable Indian-American face in Hollywood, followed far behind by that dude from 30 Rock and that dude from Heroes and that dude from Lost (who’s British and 38, so doesn’t count). And this is progress. Three years ago, he had no competitors. The Kumar trailer simply billed him as “that Indian guy from Van Wilder.” Penn credits shows like Grey’s Anatomy for shifting Hollywood’s racial landscape. But he’s selling himself short. His own comic timing and ability to believably deliver a speech equating his mission to eat at White Castle with fulfilling the American Dream have made him a legitimate pan-cultural icon all on his own. Nair says that every exterior shot in The Namesake had to be redubbed because drunken guys couldn’t help shouting, “KUMARRRR!!!” when they spotted Penn. And it was the hero worship of Nair’s 15-year-old son, Zohran, and his best friend that helped get Penn the part.

“Oh, he’s God for them!” Nair exclaims. “They get so chuffed when Kal calls.” (That’s London slang for “excited.”) “I never knew of him, really. I was casting The Namesake, and these two boys showed me Kal on the Internet and said, ‘This is your Gogol.’ And I sort of pooh-poohed them. But at night I would put Zohran to sleep and he would say to me, ‘Mama, in the morning, tell me it’s Kal Penn. Mama, tell me in the morning it’s Kal Penn.’ Literally like a mantra!”

It was Penn, though, who had first approached Nair. He’s a big reader (and Lahiri fan) who guest-lectures at colleges on “media, race, and representation.” The University of Pennsylvania has even asked him to teach two classes next fall, one on Asian-Americans in pop culture and the other on the history of teen movies (“It’s more academic than you’d think”). He was trying to buy the rights to produce The Namesake with his Kumar co-star John Cho when he found out Nair was already directing it. So he sent her a letter—“a lovely letter,” Nair recalls, “full of very seductive things to a director. He said he was an actor because of me, because when he was in eighth grade he saw Mississippi Masala in a New Jersey mall and thought that people onscreen could look like him.” Nair had cast the role, but Penn flew out on his own dime to audition anyway. “I was thinking of a young Bollywood star who had grown up in the West,” she says. “But it was folly! Kal grew up a Gogol. He was the real thing.”

Yet Penn is eager to brush off comparisons between Gogol’s upbringing and his own childhood in suburban New Jersey—for one thing, he and his parents have always gotten along. “It’s sort of like saying, ‘Gogol drank a lot of coffee growing up, I drank a lot of coffee, therefore I relate to Gogol,’ ” he says. “Gogol to me is interesting because he’s tormented by being named after a Russian author who died a virgin. I mean, his being Indian isn’t interesting in the least.”

Just before we say good-bye, Penn stops to tell a story he says he’s never told before. It’s about the last movie he shot before The Namesake, “this awful movie called Son of the Mask.” The character was named Jorge, not written as an Indian, but Penn says the director insisted he do a really thick Indian accent. There were meetings and arguments, but Penn met him halfway. Then after the film wrapped, the studio flew him back for what was supposed to be routine dubbing owing to incidental noise, only to inform him that he had to redo all his lines in a thicker accent. Penn made up a story about a meeting he couldn’t miss, did the routine dubbing, and got out. “I was livid in the car, like, Why the hell am I wasting my time being an actor if these doors are constantly going to be shut in my face?! I walk into my manager’s office and am just like, ‘Don’t ever send me back to that place again!!!’ Then I spouted off a bunch of profanities about, you know, the state of things. He’s just looking at me with this smug look, and he’s like, ‘Are you done?’ I said, ‘Yes!’ And he goes, ‘Good, because Mira just called, and you’ve booked The Namesake.’ ”