“The Chatterbox Cafe” is what Garrison Keillor calls the restaurant in his fictional upper-Minnesota town of Lake Wobegon, and it’s there I imagine him and Robert Altman having lunch to discuss A Prairie Home Companion, their fantasia on Keillor’s public-radio show. I’m not sure how much these two born-and-bred Midwesterners have in common philosophically: Keillor still grapples with his Lutheranism, while Altman treats religion more sardonically. But both men, famously taciturn, have spent their careers hovering on the sidelines watching extroverts talk past one another. That’s their point of overlap, and it’s enough to give A Prairie Home Companion an atmosphere both boisterous and holy. The movie, redolent of death, is a sort of wake, but a funny-sad one, teeming with music, corny jokes, and an ensemble of gifted performers who appear to be having an obscene amount of fun in one another’s company. That fun—and that sadness—is contagious.

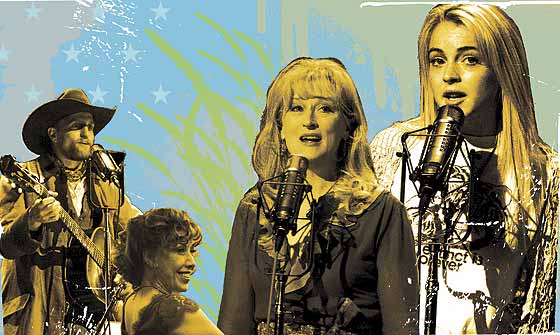

A lot of people have ridiculed the radio show over the years for what they see as elitism masquerading as folksy populism, but in the almost quarter-century I’ve been listening, what’s held me is the underlying melancholy. Big and weird-looking, rooted in a religion in which you were a sinner until proved innocent (which is never) and in a frigid place in which people were too hardy (and too buttoned-up) to dramatize their misery, Keillor could never be at home in his body. His transcendence came via that deep, plangent voice, and he went on to concoct a universe in which it could preside: a radio variety show–cum–church service, free of doctrine but with spirituals, skits, and even an oblique sermon (“News From Lake Wobegon”). The materials are shopworn, but in a good way: Keillor finds spiritual nourishment in the bric-a-brac of old radio, even in jingles for things like biscuits and duct tape. It’s not salvation, but it’s a tender mercy.Keillor sets the film on the night of the last broadcast of “A Prairie Home Companion”—here a parallel-universe show, not nearly as renowned, a casualty of its theater’s imminent demolition. Among the dramatis personae are characters from Keillor’s sketches made flesh: the detective Guy Noir (Kevin Kline), not so much radio’s rumpled gumshoe as a preening dandy, and the cowboys Dusty (John C. Reilly) and Lefty (Woody Harrelson), a rambunctious pair of pickers and crooners. The musicians are both real and fictional: bandleader Rich Dworsky; Robin and Linda Williams; Jearlyn Steele; and the Johnson sisters, Yolanda (Meryl Streep) and Rhonda (Lily Tomlin). And, of course, there is Keillor himself, both the center of the movie and a dazed bystander.

A virtuoso of flux, Altman is in his element. The camera travels up and down and side to side, trailing characters as they hurtle from dressing rooms to wings to lobby. You catch bits of babble from backstage personnel (among them radio regulars Sue Scott and Tim Russell and Saturday Night Live’s Maya Rudolph as a pregnant, harried stage manager). Altman lingers now and again on the stage—on Keillor’s musings or parts of numbers—but he’s easily distracted. A car pulls up with the Axeman (Tommy Lee Jones), a steel-spectacled, Scripture-quoting company worm there to watch the death of a theater. And on a more surreal note, death itself arrives in the form of a golden-haired woman (Virginia Madsen) who comes to enfold a performer in a loving embrace.

The ingenue-of-death thing is dicey, the staging a little flat; it’s only Madsen’s unaffected radiance and Kline’s over-the-top infatuation—she’s the dame of his dreams—that keep the device from being utterly risible. Sometimes you forget how great an actor is, then he or she is reborn in an Altman movie. It happens with Kline, a master of athletic deadpan who elegantly lights a cigarette and nearly burns off his mustache. Streep is just as brilliant. Her Yolanda is a goosy creature with sloppy cleavage and a Minnesota twitter: It might have been a caricature, but when she plays a performer, a childish joy breaks through her often overcontrolled demeanor. And if Tomlin’s face has become a bit of a mask in recent years, her dryness makes her Streep’s perfect foil—and her timing is as gorgeous as ever.

A Prairie Home Companion has off notes. Keillor’s writing is too glib for Yolanda’s high-school daughter, who pens bad poems about suicide, and the casting of Lindsay Lohan throws you out of the movie (although she’s not bad). And Keillor isn’t a film actor. It’s not that features are squashed in the middle of his big head. It’s that he’s simply too well defended—too insulated—to open himself up to the camera. Inexplicably, there’s no “News From Lake Wobegon,” which might have accounted for his defenses and connected some of the movie’s dots.

Altman has never been one for connecting dots, but even he can’t escape the insistent subtext. At 81, with an honorary Oscar (the kind that might as well be shaped like a tombstone), our greatest living American director has likely thought once or twice about the arrival of Virginia Madsen. But given the unruly vitality of this marvelous film, it’s also likely he’s thinking of her in more ways than one.

Yet another remake no one needs is The Omen, based on an empty 1976 horror vessel that caught the public’s imagination largely because of a juicy Jerry Goldsmith score and a state-of-the-art Rube Goldberg plate-glass decapitation. With minor variations, John Moore’s version is a beat-for-beat copy. It feels predetermined—and I don’t mean it was predicted in Revelations.

Last time, the joke was that all-American archetypes Gregory Peck and Lee Remick played the parents of the Antichrist—a joke that’s lost with the more naturalistic Liev Schreiber (does his word-processing program automatically change his name to “Live” the way mine does?) and Julia Stiles. The stunt casting in this one is Mia Farrow, once the Antichrist’s unwitting mom and now his witting—and devilishly cheerful—nanny. Moore is a resourceful director, but the Final Destination movies have set the bar pretty high on Rube Goldberg splatter.

There ought to be creepier overtones in a modern Omen, what with even non-religiosos like me worrying that we’re approaching the End of Days. The remake does open with (exploitative, offensive) footage of the World Trade Center collapsing, the space shuttle exploding, etc.—the sorts of disasters that make Pat Robertson nod and say, “That’s what comes of gay marriage.” Maybe it’s time to revise our notions of the Devil. The people who have put this world in peril believe that God is on their side.

BACKSTORY

Mia Farrow was famously entangled with Woody Allen for twelve years and one boldface adopted child (Soon-Yi)—and she married both André Previn and Frank Sinatra, whom she dishes on in the new issue of Esquire. “When I married Frank, my father had died recently, and people said, ‘Oh, you’re looking for a father.’ It’s hard for me to, um, deny or confirm. But what I will tell you is that he was the coolest, handsomest, sexiest guy. I don’t think there are many women of any age who could have resisted him … So you can talk ‘father’ all you like—he wasn’t anything like my father!”

A Prairie

Home Companion

Directed by

Robert Altman.

Picturehouse.

PG-13.

The Omen

Directed by

John Moore.

Twentieth Century Fox. R.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com