Radically different as they are, Doug Liman’s agitated Jumper and Michel Gondry’s amiably limp Be Kind Rewind appeal to the same part of the modern couch-potato psyche—the part that dreams of sailing off the couch and merging with the action onscreen. Liman cunningly exploits our addiction to instant gratification: His hero can teleport himself anywhere, from two butt-lengths down the sofa to pick up the TV remote to half a world away for lunch atop the Sphinx. But Gondry, whose stumblebum heroes remake Hollywood blockbusters with one video camera and no budget, is the true transcendentalist. He wants to work through the standard-issue solipsistic superhero daydream and find, among pop-culture lovers, a source of communion. Neither film entirely works, but it’s fun to regard them side by side: a state-of-the-art escapist fantasy and its threadbare postmodern travesty.

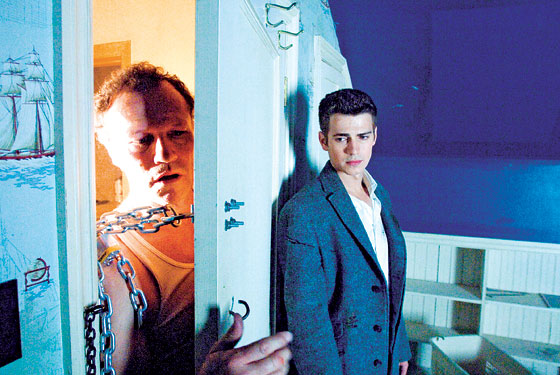

Jumper isn’t explicitly about movies, but its reality is virtual. David Rice, played by Max Thieriot as a youth and Hayden Christensen when he’s taller and less expressive, grows up with a drunk for a dad (Michael Rooker) and no mom. And when he’s liberated by his ability to “jump” (there’s no explanation for his gift, but who needs one, really?) he does what any alienated youth with superpowers would do—move to New York and rob banks. Later they’ll pander like mad, but Liman and his screenwriters make a bracing joke out of David’s refusal to use his talents for “good”: He watches on TV as Katrina victims call for help from their rooftops, then jumps to England to get laid. But something terrifying stands between David and boundless self-gratification: a murderous sect of Jumper-hunters called Palladins, who catch their prey in electrified spiderwebs, proclaim them abominations in the eyes of God, and disembowel them. The Palladins are led by Samuel L. Jackson with white fungus on his head—either it’s the worst rug ever or Jackson is a mushroom from space.

Jumper is so in sync with the language of modern action movies that it’s possible to look past its soullessness and go with the quantum flow. Jump-cuts are the rule in thrillers like The Bourne Identity (which Liman directed). Here, the faster and choppier Liman gets, the truer he is to his hyperkinetic premise. Fisticuffs begin on one continent, continue on another, and end in a third: It’s Around the World in Eighty Blows.

It would have worked better, though, with a livelier leading man. What is it about Christensen’s voice that’s so dead, even without dialogue by George Lucas? Is he trying to suppress his Canadian accent? The one he uses is from nowhere, and it wipes out the impact of his eyes, which occasionally flash with authentic anger. David has a dull affair with Millie (Rachel Bilson), the girl who was nice to him in high school. (It begins after a bar fight, when Millie says, “You’re bleeding a little; we should take care of that”—has that line ever not been a prelude to sex?) But the big disconnect at the heart of Jumper is that a guy who doesn’t walk anywhere doesn’t have an ounce of flab and even jumps to Fiji to surf the big waves. His muscles should have atrophied years ago.

Jumper has a lot of buzz, but I can imagine near riots at the nonending, which plays like the fade-out of a TV pilot: Almost everyone is still alive and glowering. If you’re a Hollywood executive, you can’t just deliver a hit movie anymore; you only get the big bonus for delivering a “franchise.” But I can’t see people lining up for a sequel—unless Samuel Jackson’s hair grows out and marches on Tokyo.

I can see Mos Def affixing powdered Astroturf to his scalp to take Jackson’s role in the Be Kind Rewind remake of Jumper, hurtling through space after Jack Black—who certainly looks like a couch potato. Def plays Mike, a clerk in a dilapidated Passaic, New Jersey, video store that still rents tapes—because the owner, Mr. Fletcher (Danny Glover with convincing salt-and-pepper hair), is stubbornly behind the times. How’s this for a setup? Mike’s crazy-paranoid pal Jerry (Black) gets electrocuted, picks up a magnetic charge, and inadvertently erases all the store’s tapes. Because the building is on the verge of being turned into condos, Jerry and Mike have to keep the money flowing in—which means shooting their own zero-budget versions of FX-heavy blockbusters like Ghostbusters, Rush Hour 2, and RoboCop. It’s “let’s put on a show” as “let’s make a movie.” Because this is a fairy tale, the customers who rent these tapes don’t come back with baseball bats but with fervent requests for more remakes—or “Swedes,” in the film’s distinctive patois. All would go swimmingly but for Hollywood’s pesky obsession with copyright infringement.

To call the narrative shambling and the acting amateurish is not wholly an insult, because Be Kind Rewind is determinedly unslick. Gondry, like many French-born filmmakers, has the Big Deconstructionist Idea. He’s exploring the gulf between the democratization of moviemaking and the daunting amount of money, technical resources, and personnel it takes to make anything that the mainstream audience will want to see. He’s also showing how far a little bit of wit and humanity can go. In The Science of Sleep and many of his music videos, Gondry’s designs are right on the border between CGI-miraculous and handmade—manufactured realities that draw attention to their childish surrealism. The funniest things in Be Kind Rewind are not the many moments in which Mike and Jerry look like Ed Wood’s worst nightmare, but when the pair finds expedient ways to do for pennies what would take Brett Ratner millions and be less expressive to boot.

A little slickness would not have been misplaced, though. Mos Def, a gifted actor, is on simpleton autopilot, and Black would be a better clown if he were physically more inventive. A narrative this outlandish requires the characters to act like borderline mental defectives, which reins in both Glover and Mia Farrow, who plays a kind of child-woman neighbor. Gondry might think he’s parodying dumb comedies in which poor people rally to save beloved institutions from foreclosure—but too often Be Kind Rewind just resembles them.

Fats Waller holds this ramshackle picture together. He’s Mr. Fletcher’s idol—the source of the old man’s dreams and civic pride, and the subject of the movie’s final act. It’s a soft ending, a little woozy (or, at least, it made me woozy). But it radiates the kind of optimism you don’t see in films about how new media is turning us all into passive voyeurs in our own hermetically sealed bubbles. This bubble is warm and inclusive.

With the simplest of means, the director Jacques Rivette has cut a path to the heart of Balzac’s The Duchess of Langeais, one of the author’s less transgressive studies in sexual obsession but dizzyingly potent in charting the pendulum swings of power between willful lovers. Rivette has pared the story down so that there isn’t a wasted frame. The Duchess, Antoinette (Jeanne Balibar), estranged from her husband, brings a battered military hero, General Armand de Montriveau (Guillaume Depardieu), into her orbit: She converses with him while wriggling on her settee; uses him to escort her nightly to extravagant functions; and preserves her “virtue” by airily withholding her sexual favors. (“She had so pretty an art of revoking the grant of yesterday,” writes Balzac.)

Balibar isn’t conventionally beautiful, but her face is pert, provocatively forward—you can see why Montriveau wants to seize her. Depardieu (Gérard’s son) is too stolid to capture the full range of the general’s emotions: What’s missing is the adolescent delight in the early scenes, when he’s giddy from the novelty of not holding the reins—a contrast with the Napoleonic near madman who emerges after months of denial. But Depardieu certainly evokes Montriveau’s masculine sense of entitlement and ease in commanding a secret male society with no checks on its power. No wonder Antoinette can only find (temporary) refuge in an order of Carmelite nuns.

Rivette has aged into one of cinema’s most ingenious minimalists. In The Duchess of Langeais he uses intertitles—bits of literary exposition—with cheeky understatement. It’s as if he’s reminding us that he doesn’t need pages of characters’ thoughts to show the fullness of their inner worlds. Even when the camera is still, the crosscurrents are electric.

BACKSTORY

Six months after The Duchess of Langeais opens here, a second Duchess will appear—another bewigged period film, but this one with Keira Knightley as Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire, a spendthrift and promiscuous ancestor of Princess Di. Although film studios labor for original titles, they can’t be copyrighted. In 2005, Slate dedicated a column to title duplication, pegged to the release of Will Ferrell’s soccer-coach comedy Kicking & Screaming, which bore no relation to Noah Baumbach’s 1995 debut, Kicking and Screaming. That same year, Paul Haggis released Crash, not to be confused (car troubles aside) with David Cronenberg’s 1996 film.

Jumper

Directed by Doug Liman.

20th Century Fox. PG-13.

Be Kind Rewind

Directed by Michel Gondry.

New Line Cinema. PG-13.

The Duchess of Langeais

Directed by Jacques Rivette.

IFC Films. NR.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.