Watching the coolly ironic documentary Full Battle Rattle, one’s heart goes out to Lieutenant Colonel Robert McLaughlin as he sits in a daze in front of his desert headquarters, having seen most of his battalion slaughtered the night before by Iraqi insurgents. “Am I a failure?” he asks, then answers, “Actions speak louder than words.” The poor man: He did his diligent best to bring order to the tiny village of Medina Wasl. His men murdered only a few innocent civilians, and he more or less averted civil war between Sunnis and Shiites after the assassination of the deputy mayor’s son (on video, to shouts of “Allahu Akbar!”). The worst part is that there he was on camera when the massacre of his men went down, celebrating the return of authority to the Iraqi mayor. (“Jobs are coming back to the community!”) Now he has to eulogize the dead. Then he has to pack up and head to Iraq and do it for real—and hope to God that life doesn’t replicate art.

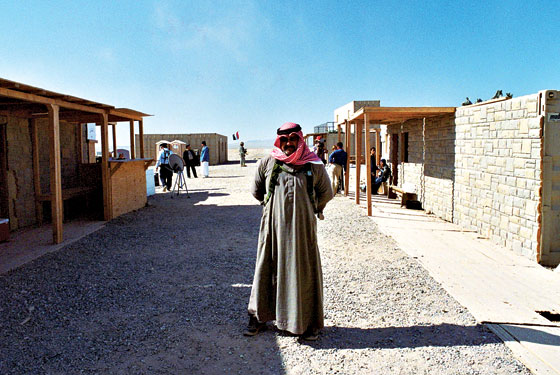

Full Battle Rattle is an indelible vision of modern war, a not-so-fun fun-house mirror of the Iraq occupation set in California’s Mojave Desert. The place, 1,200 miles square, is called the National Training Center—a billion-dollar “virtual Iraq” at Fort Irwin with an acting troupe of hundreds (many of them Iraqi immigrants), in which military personnel get a mini-jolt of what they’re in for. The film is freaky, amusing, and sickening in equal measures—part fly-on-the-wall vérité, part multiple-perspective Altmanesque tragicomedy. Soldiers writhe on the ground choking in their blood, and then Americans and Iraqis pick themselves up and stand in line at ice-cream trucks; it’s like Disney World with the fireworks aimed lower.

Directors Tony Gerber and Jesse Moss don’t lead with their politics, whatever they might be. And on one level, the mere existence of the center is reassuring: Conventional antiwar wisdom holds that the Cheney-Rumsfeld armchair warmongers had little regard for the welfare of young, inexperienced soldiers with no knowledge of Iraqi culture. That might have been true at the outset of the occupation, but now our tax dollars are at work creating a kind of alternate reality show in which “simulation architects” concoct intricate scenarios (miscommunications, suicide bombings) and devise meaty roles for Iraqis who worry they’re somehow betraying the folks back home. But they need the money—often to send to the folks back home.

The less reassuring part is that the situation—even fictionalized, softened, without the crucial components of lawless private contractors and reconstruction stalled by incompetence and fraud—is borderline hopeless. Full Battle Rattle begins as a showbiz comedy, with an almost stoned view of the occupation, but gradually the bottom crumbles and drops out. The plastic dummies of dead soldiers have wounds modeled on actual casualties—they’re horrifying. The reenactments, meanwhile, take on a mystical quality: The masks become real. The Iraqi actors—who know that the political (and physical) infrastructure of their country has collapsed, who still have families in peril—look askance (no matter what their script says) when McLaughlin tells them that the U.S. will guarantee their security. A soldier admits there are moments when he despises the Iraqis, even though he knows they’re actors. An illegal Iraqi immigrant, Nagi, who plays a policeman, works like mad to ingratiate himself with the officers: Maybe if he helps the Americans he will not be sent back, where he will probably be killed for collaborating. It’s a little like what happens to real Iraqi policemen—except most of them die.

The only subjects in Full Battle Rattle having a whale of a time are the Americans who play Iraqi insurgents. Gerber and Moss track their planning sessions; the men all but rub their hands with glee at the prospect of causing chaos instead of trying to prevent it. They get to pick off the enemy the way soldiers do in movies, the way Americans can’t in a war they should never have been fighting—here a catastrophic farce, a let’s-pretend that ends with a mass deployment to hell.

This season’s crop of computer-generated superhero blockbusters has been more than decent (even the shambolic Hancock has a good gonzo moment or two in the first half), but am I the only one who’s jaded by the sight of special effects throwing other special effects through walls? Two more biggies open this week, Hellboy II: The Golden Army and Journey to the Center of the Earth, and both have modest charms—enough to overcome my CG-ennui for at least a few scenes.

The first is Guillermo del Toro’s busy follow-up to his comic-book saga about a little devil (literally) who grows up to be a big devil (Ron Perlman) and fight squiggly FX while chomping on stogies. Hellboy’s persona is a parody of macho action heroes, but because of the red skin and horns and tail he’s forced to live in an underground government lair with a lot of fellow mutants—not a happy place for a natural-born hell-raiser. The original worked because Del Toro is a fan-boy who exults in both his hero’s crash-and-bash potency and his morbid spiritual dislocation. (He has always had a thing for subterranean caverns.) In the sequel, Hellboy and his darkly neurotic squeeze (Selma Blair)—she flames up when she’s mad—are at each other’s throats, while a white-faced demon prince (Luke Goss) with a mean martial-arts blade kills a lot of people with particularly nasty FX. Amiable fish-man Abe Sapien (Doug Jones) falls for the prince’s blonde sister (Anna Walton) and they all end up in Scotland fighting bigger FX. The best scene is when Hellboy and Abe get drunk and sing out raucously, which after Hancock suggests a trend toward superhero alcoholism. The economy?

Journey to the Center of the Earth, in which morose hunky scientist Brendan Fraser, his nephew (Josh Hutcherson), and a blue-eyed Icelandic babe (Anita Briem) roller-coaster down a mine shaft, fall into a chasm, and get chased by dinosaurs, is clunkier and more simpleminded. It would be barely passable under normal circumstances, but in 3-D it’s a circus of excellent FX. You get the always-good-for-a-laugh yo-yo-in-your-face, some spat-out mouthwash, many sharp objects, snapping dino jaws, a cute little bluebird, and even monster pus. With the glasses on, the image is a little dark, and the underground oceans and forests look fakey fakey. But who cares when the background is actually back and the foreground so fore it seems to tickle your nostril hairs? If today’s movies take place inside computers anyway, it’s nice when the technology can usher us inside, too.

In The Wackness, Josh Peck, of Nickelodeon’s excruciating (for non-tweens) sitcom Drake & Josh, plays a recent high-school grad who wheels around an ice-cream cart selling pot, some of it to his long-haired stoner psychiatrist (Sir Ben Kingsley), while lusting after the doctor’s willowy stepdaughter (Olivia Thirlby). The writer and director, Jonathan Levine, labors to establish the period (it’s 1994), which means a lot of white kids talking like rappers and ominous signs (for drug dealers) of a Giuliani crackdown on New York crime. The movie feels autobiographical—emotionally authentic (with a fair amount of bitterness toward women) and somewhat unshaped. The Giuliani stuff doesn’t come to anything, and Peck needs to learn that even dazed-and-confused teens don’t let their mouths hang slackly open all the time. The fun is watching Thirlby—second banana in Juno—do a tantalizing sex-bomb number, and Kingsley get to flout his knighthood by sticking his tongue down the throat of Mary-Kate Olsen.

The big film opening of June was the latest Pixar triumph, Andrew Stanton’s Wall-E, which screened too late (Why, Disney, why?) to be reviewed in this magazine’s double issue of two weeks back. You can read my full paean to its beauties here, but it’s worth restating the thesis: that the movie is essentially a parable of two children, Wall-E and Eve, who restore the connection between humans and the natural world. Pixar, a beacon for the future of film technology, has defined itself by telling stories of loss, decay, and the dark side of materialism, with a tension between childhood wonder (inspired by old toys, cars, movies) and the disengagement brought on by growing up in a fast-paced cyber world (CG-ennui, anyone?). It’s as if simple machines hold memories that aging humans forget. What a peculiar company this is, forward- and backward-looking, a technological Janus head, using all its computer resources to warn us that computers are stealing our souls.

BACKSTORY

After Hellboy grossed $100 million, you’d expect the sequel would be smooth sailing. When Revolution Studios went belly up, Hellboy II was left in limbo. Universal acquired the rights, but it was the boffo success of Pan’s Labyrinth—$83 million on a $19 million budget— that gave director Guillermo Del Toro leverage. Co-producer and Hellboy creator Mike Mignola told the video-gaming site IGN.com that the “old gods” and elves replace the first film’s “Nazis, machines, and mad scientists,” creating a new conflict: “I kind of equate it to the whole American Indian situation. The main difference is, What if the Indians had a nuclear warhead?”

Full Battle Rattle

Directed by Tony Gerber and Jesse Moss.

Mile End Films. NR.

Hellboy II: The Golden Army

Directed by Guillermo del Toro.

Universal Pictures. PG-13.

Journey to the Center of the Earth

Directed by Eric Brevig

Warner Bros. PG.

The Wackness

Directed by Jonathan Levine.

Sony Pictures Classics. R.

E-mail: filmcritic@newyorkmag.com.