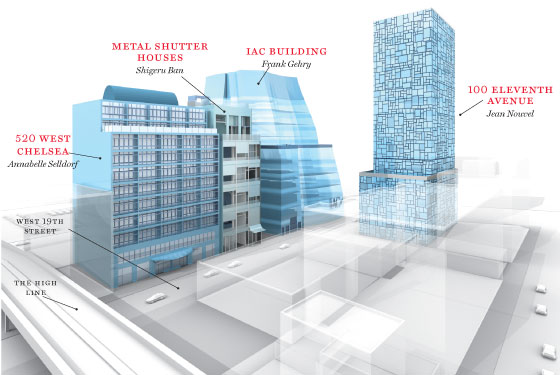

Until a few years ago, West 19th Street between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues was best known as the heart of West Chelsea’s parking-lot district, a windy, nondescript strip that ducked beneath the rusting High Line and terminated at the West Side Highway. A few art galleries and the Kitchen gave it a certain grunge glamour. Now, driven by the High Line at one end of the block, inspired by the presence of a Frank Gehry office building at the other, and invigorated by the financial premium attached to marquee architects, developers are transforming these few dozen feet of sidewalk into a living anthology of contemporary design. Within a couple of years, condos by Annabelle Selldorf, Shigeru Ban, and Jean Nouvel will cluster together here, marking the epicenter of Chelsea’s coming metamorphosis. No other city block in America will have such a concentration of high-end architecture. That’s partly because a year before it opens, the High Line’s elevated park is being billed as the amenity to end all amenities, and partly because the whole point of hiring a star to design an apartment building is to keep New York’s luxury-real-estate market on an outer orbit of its own. The architectural efflorescence of West 19th Street depends on the wealthy’s wanting to live in a new building the rest of us can only take pictures of, in a neighborhood just funky enough to make them feel like pioneers.

Gehry’s IAC Building—the one that made the street safe for fancy architecture—stands at one end, its white glass walls billowing like a lace curtain, with the Hudson just beyond. Its immediate next-door neighbor on the south side of 19th Street will be Ban’s Metal Shutter Houses, an eleven-story multimillionaire’s enclave by an architect who made his reputation designing shelter for the traumatized and poor. When residents are in an expansive mood, they can flick a switch and an entire glass wall at either end of the living room will roll upward like a garage door, opening their abode to the elements. In lockdown mode, the glass walls swing shut and a perforated metal screen rolls down, rather like a fabric shade or a store shutter. Call it bodega chic.

Happily, the 19th Street architects have found no need to reinvent the city from scratch: Chelsea is not Dubai. Ban’s shutters recall the neighborhood’s warehouse past; right next door, Selldorf reinterprets an old New York tradition with modernist flair. Her 520 West Chelsea wears a suit of curved terra-cotta tiles glazed in midnight blue—the kind of material we tend to associate with bathrooms now but that 80 years ago speckled this gray city with shiny white façades and flecks of brilliant color. Terra-cotta, with its combination of smoothness, texture, and deep hues, is making a modernist comeback, thanks to Selldorf as well as to Brad Cloepfil, who is just now covering the shrouded 2 Columbus Circle with glazed iridescent tiles.

Both Ban’s and Selldorf’s creations, which would be stars anywhere else, may get overshadowed by their more brazen neighbor across the street: Nouvel’s 100 Eleventh Avenue. At 23 stories, it’s tall for this area, and two of its façades will get a sequined look that could even divert the eye from Gehry. Instead of facing the building with a sheer glass curtain wall, Nouvel has specified windows of odd sizes, set at angles to catch the sunlight in assorted ways. Especially in the evening, the façade might evoke different memories of New York, as its shiny squares reflect the sunset like a disco ball. If Nouvel can make fine architecture out of a cheesy association, more power to him.