A car careers into Sheepshead Bay, with two children and a mother who can’t swim …

A cool October evening on Sheepshead Bay. Keith Gorman, a 42-year-old fisherman, is on Pier Five when he hears a tremendous racket. Everybody runs toward Pier Seven, where a silver sedan carrying a Staten Island woman and her two teenage daughters had smashed through a protective barrier and started sinking into the harbor. Pandemonium. Gorman fights through the crowd and dives into the water. One of the daughters is in the back seat screaming that her mother can’t swim. “I tell her to get out of the car,” Gorman says, and she scrambles out the window. The two girls climb onto the roof and are lifted to safety. Gorman turns his attention to the mother, who is waist-deep in water. “You gotta get out of this car,” he says. He rips off her seat belt, pulls her out by her arms, and pushes her onto the roof of the car. By the time the fire trucks and ambulances arrive, the car is completely submerged. Gorman signs papers declining a trip to the hospital, finds dry clothes, and goes to work.

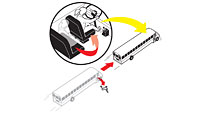

A school bus barrels toward a red light, its driver dead and nine campers screaming …

Rachel Guzy, a 16-year-old camp counselor at Magic Carpet Day Camp in Bayside, is in a school bus with nine campers, ages 7 to 14. With no air-conditioning and temperatures in the nineties, the bus driver, Salvador Ramon Fernandez, has the front door open. Guzy calls out a question to Fernandez, but no response: She looks up to see him slumped over the steering wheel, dead from a heart attack. Fernandez falls out of his seat, through the open door, and onto the pavement. The children begin to scream. The bus charges through a red light at an intersection, clips the back end of a minivan, and is headed for the line of cars parked along the avenue. Guzy, who doesn’t even have a learner’s permit, bounds into the driver’s seat, steps on the floor brake, and yanks the parking brake. The bus lurches to a halt. Guzy tells the screaming children not to look out the window at poor Salvador, then runs out to check on him. She calls 911 and tells the kids to stay on the bus until the cops arrive on the scene.

A drunken man falls onto the tracks as a PATH train approaches …

It’s 11:45 p.m. at the Christopher Street path station in late February, and roughly 50 passengers are standing on the platform. Terrence Kelsor, a path train station security agent, observes a seemingly intoxicated Caucasian male, upwards of 250 pounds, fall onto the tracks. “I immediately spring into action,” Kelsor says. “We’re supposed to dial a four-digit number on our radio and notify the train master to stop. I didn’t have time for that, though.” He can see a train approaching, and estimates that he has about ten seconds. “I begin counting to ten—one, two, three, four—and man, my adrenaline is pumping!” He gets on his belly and reaches down, half his body dangling over the tracks. The man is not responsive. As the other passengers watch, Kelsor (170 pounds, but “in pretty good shape—my wife can tell you”) grabs the man by the underarms—five, six, seven—then by the seat of his pants, and lifts 250 pounds of dead weight—eight, nine—onto the platform. Ten. The train roars into the station.