Andrew Cuomo, the attorney general of New York State, sat in his 25th-floor office, high above Wall Street, watching as months of his work burst onto national television. Down in Washington, D.C., Edward Liddy, the beleaguered head of AIG, was sweating in the witness chair as a congressional committee berated him for trying to sneak $165 million in bonuses past their righteous noses. President Obama was outraged, too, ordering the Treasury Department to try to reclaim the cash.

Cuomo sat back and watched the furor build to a crescendo. Since last year, he’d become the prime agent of populist rage, clawing back exorbitant bonus money here, venting anger on behalf of the taxpayers there. Cuomo turned up the tension with well-timed leaks and subpoenas, seizing on the juiciest details: partridge-hunting trips paid for with federal bailout money! Resort junkets! The public outrage had been a useful tool, forcing AIG to freeze payments to executives and, not coincidentally, making Cuomo wildly popular.

But Cuomo could feel the momentum shifting as he listened to Liddy testify. The AIG boss was reading from vicious death threats made against his employees. Cuomo had seen this turning point coming; his office had been checking out the threats. He knew the time for ratcheting up the pressure was running out. Cuomo’s threat to release the names of bonus recipients would soon start to look like pure demagoguery. And if, God forbid, some nut took a shot at some banker in his driveway up in Greenwich? Cuomo might be blamed.

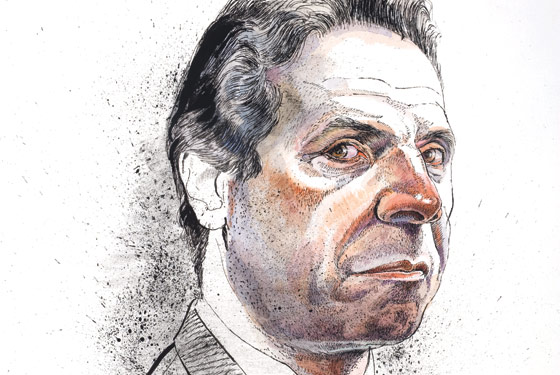

For most of his life, Cuomo had known only one speed: all-out attack mode. But 35 years in politics—from seventies street fights against Ed Koch to being his father’s right hand in Albany to serving as Cabinet secretary in the Clinton White House—had shown him that he had better learn to see around the corner, around the next three corners. The mistakes that nearly ended his political career came when he didn’t look far enough ahead or thought he could simply put his head down and bull his way through. The tendency had earned him a reputation as one of the darkest characters in New York politics—vindictive, arrogant, a bully with a nasty temper. Now, at 51, he’d found an appropriate target for his anger. But he’d finally learned when to back off.

Wall Street’s collapse has created a bonanza of juicy investigative opportunities for Cuomo, putting him on the national stage and giving him the opening to recast himself as a populist hero. Cuomo has craftily walked a fine line, knowing when to push and how hard, injecting himself into huge issues while staying mostly out of camera range. His office continues to rack up major successes—just last week, his ongoing investigation of the $125 billion state pension fund produced the arrest of another New York power broker, plus a $12 million settlement and a guilty plea from a corrupt hedge-fund manager, as he picked off aides and associates of former comptroller Alan Hevesi.

While Cuomo has been masterfully manipulating public sentiment, his erstwhile political rivals have been taking themselves out of the equation—Eliot Spitzer by sleeping his way out of the governor’s office, and David Paterson by racking up a string of unforced errors. Circumstances have conspired to set up Cuomo perfectly for a gubernatorial run in 2010. But his newfound political acumen will be tested over the next year. Last week, the pension-fund investigation reached higher up the rungs of political power, touching the Republican-connected Carlyle Group and Steven Rattner, the New York investor, Democratic fund-raiser, and Obama-administration car czar. Will Cuomo keep pushing the probe without fear or favor? Can he nudge Paterson aside without appearing to push too hard? Can he continue to ride the populist wave without running aground? “The Andrew Cuomo I first met 30 years ago would not be able to,” a veteran political consultant says. “The Andrew Cuomo of 2009 is absolutely capable of doing it.”

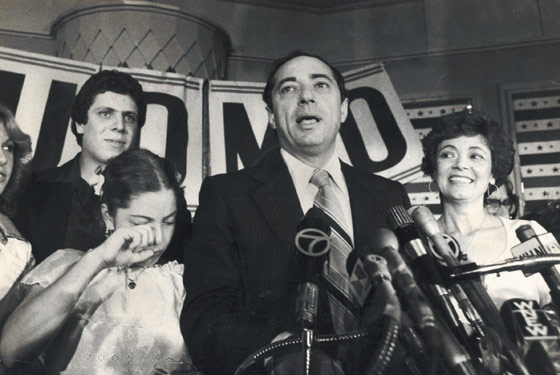

Andrew Cuomo has been obsessed with the governorship since his father Mario’s upset victory in 1982. Twenty-four-year-old Andrew had managed the campaign, and after the win, became his father’s counselor and hard-fisted enforcer until 1993, when President Bill Clinton brought him to Washington as assistant secretary of HUD. After Mario’s career-ending loss to George Pataki in 1994, Andrew focused on avenging his father’s defeat. In 2001, he returned to New York from Washington, where he’d risen to HUD secretary, and began to campaign.

The only problem was that Carl McCall, the state comptroller and New York’s first African-American statewide official, was considered next in line by many Democratic leaders. “Everyone told him it was a mistake,” a political friend says. “He wanted to do it because he figured he could take out McCall.” Without the support of the party, and with the enmity of black pols, Cuomo’s campaign went nowhere. He skipped the state convention, then quit the race one week before the Democratic primary. That debacle was followed a year later by the very public collapse of Cuomo’s marriage to Kerry Kennedy, the seventh child of the late Robert F. Kennedy. Cuomo’s lawyer was quoted in a Times story saying his soon-to-be-ex-wife had “betrayed” him. “It was the old Cuomo-family reflex: Turn every problem into a political attack,” a family friend says.

Cuomo’s friends say he’s been mellowed by his political losses and the breakup of his marriage, that he’s a sensitive man whose hard edge has always been exaggerated by enemies. “He’s a complicated individual in some respects, and he’s been evolving, a lot, over the past few years,” a longtime family friend says. “When you get the shit kicked out of you a couple times, it forces you to reevaluate what matters. I don’t want to say it humanized him, but he realized, as he said to me, that there’s a certain randomness to life. He used to think he could control everything, and he found out he can’t control much of anything. He’s become less obsessive.”

And more disciplined. Historically not one to shy away from the spotlight, Cuomo has lately allowed the attention to come to him. What’s particularly striking about his rise to national prominence is that it’s happened during a period in which he has turned down almost all interview requests, speaking to reporters primarily through conference calls.

His critics are not convinced that he’s a new man. “Are you kidding me?” scoffs an elected official who has known Cuomo a long time. “Whatever virtues and defects Andrew has have only been concentrated by age.” Perhaps he’s simply learned the subtler art of getting what he wants by persuasion rather than by force. Cuomo can be quite engaging. “He’s a seducer,” a political consultant says. “He genuinely likes people in a way Mario never did.”

Father and son are close and oddly distant at the same time, yet political allies to the end. In 2006, after Andrew had given up on running against Spitzer for governor and decided to try to succeed him as attorney general, Mario swung into action. The former governor was troubled by a bitter feud with Ed Koch that had simmered since the 1977 mayoral campaign, when posters reading VOTE FOR CUOMO, NOT THE HOMO appeared. The Cuomo campaign denied responsibility; Koch didn’t buy it. Now, with both men in their golden years, Mario thought perhaps they could finally let bygones be bygones. One morning at the Regency Hotel restaurant, long a prime spot for political players, he approached George Arzt, a longtime New York Democratic strategist. “Mario came over to me and said, ‘Isn’t it time that Ed and I finally settled whatever ill feeling there was?’ ” Arzt recalls. “I said, ‘What did you have in mind?’ Mario said, ‘Ed endorsing my son.’ ” Koch agreed. Though it was a nice gesture, Andrew didn’t really need his father to broker endorsements for him. He won the race easily.

“Andrew is orchestrating all of it to construct the conclusion that Paterson shouldn’t run. That’s his endgame.”

Spitzer, now governor, was extremely wary of Cuomo in the attorney-general post. “Eliot kept saying, ‘The first chance Andrew gets, he’s gonna fuck us. Mark my words,’ ” a former Spitzer aide says. And it wasn’t long before, in their eyes anyway, he did. In July 2007, after Joe Bruno, the powerful leader of the State Senate Republicans, accused Spitzer of using the state police to spy on him, Cuomo issued a rapidly assembled report that shed a harsh light on the tactics of the governor’s staff.

Otherwise, Cuomo seemed determined to build a new image as earnestly working for his constituents: He won praise for forcing eighteen student-loan companies to clean up their acts and later compelled UnitedHealth, the state’s largest medical insurer, to stop shortchanging customers. The one place he didn’t seem to be racking up wins for the little guy was Wall Street. “The office was slow out of the gate on financial-industry cases,” a New York white-collar defense attorney says. “It was clear from the outset that the Cuomo folks weren’t going to engage in criticisms and activities that were directed toward the financial markets.”

A Cuomo deputy insists it was a matter of tone, not tenacity, and an intentional contrast to the way Spitzer had run the AG’s office. “Andrew came in and said, ‘I want to do it a little differently: I want to do it cooperatively. Let’s get industries to agree to reform themselves, by working with them, in ways they can handle, so it won’t kill the company,’ ” says the aide. “Andrew has wanted, as AG, to, whenever possible, not end up fighting in a personal way with Wall Street.”

But as the financial industry came completely unglued, he seized the opportunity for huge political profit with minimal risk. Cuomo issued requests for compensation information from all the major financial institutions receiving federal money; when banks dodged, he scolded them and issued subpoenas. Goldman Sachs and Citigroup, among others, eventually agreed to suspend or shrink bonuses for senior executives.

Cuomo’s policing of the excesses exposed by the financial-system meltdown has raised a sticky question, however: Did he have a role in enabling the boom in subprime mortgages that contributed to the disaster? As detailed by Wayne Barrett in an August 2008 Village Voice cover story, Cuomo, as hud secretary, pushed to expand the issuance of loans to low-income borrowers. Cuomo’s defenders say he merely wanted to make home ownership easier for consumers who had been unfairly shut out of the mortgage market—and that the mortgage companies ran wild only after the Republicans took over. “To say Andrew Cuomo is in any way responsible for what happened at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is absurd,” a Cuomo spokesman says.

If Cuomo’s tenure at HUD produced murky results, it’s even less clear what he’s accomplished in his battles with Wall Street. His record draws ridicule from veterans of Spitzer’s pugilistic years. “He’s been very, very weak on settlements,” a former prosecutor says. “In many cases he’ll find an issue and do a quick resolution that involves new industry standards or best practices and a smallish fine, and he’ll move on. As a lawyer and a regulator, he’s a lightweight.”

Less partisan observers, however, give Cuomo higher marks. “He was the first person to get a real settlement in the auction-rate-securities case,” says John Coffee, a Columbia Law School professor and expert in securities law. Cuomo accused banks of misleading investors about the safety of these bonds. “The SEC may have extended the settlement, but it wouldn’t have happened without Cuomo being there first.”

Even if it’s too early to tell if Cuomo has accomplished anything of long-term substance in his engagement with Wall Street, it’s clear that as political theater, it’s been a brilliant run. “The interesting thing about coming after Spitzer,” a New York defense lawyer says, “is that you can be pretty aggressive, pretty press-hungry, pretty self-congratulatory—and still look like a pretty reasonable guy.”

Ben Lawsky is surrounded by his boss’s growing fame. On a spring Friday afternoon, the 39-year-old attorney—one of Cuomo’s top lieutenants—is sitting at his office desk in the financial district. To Lawsky’s right, his computer screen is playing a 2007 video of Jim Cramer blistering Cuomo for investigating home-mortgage companies. To Lawsky’s left is a television, tuned to CNBC. Suddenly, a live shot from the White House lawn pops up.

“Hey, it’s my friend Ken Lewis,” Lawsky says with a laugh. A month earlier, Lawsky made the Bank of America CEO squirm as he deposed him for not surrendering the names of bankers who’d received millions in bonus payments.

Lawsky’s phone rings. It’s the office of Barney Frank, the Massachusetts congressman who, with Cuomo’s help, has been leading the Washington charge against profligate corporations. For the last six months, Cuomo’s office has been headquarters for the political and legal war on Wall Street.

“In October, Andrew had become very interested in these compensation issues,” Lawsky says. “His feeling was, if a bank or a firm was getting federal bailout money, they have new duties, of at least transparency and maybe even fiduciary-type duties to the taxpayers. When they put out bonuses, they should be justified. We spent a long weekend, with our biggest brains here, thinking a lot about New York law. What we were trying to figure out was, what was our basis to investigate this stuff? And we came up with this fraudulent-conveyance law.”

To oversimplify, Cuomo argued that New York is a creditor of firms that take federal bailout money, and so the state’s lawyer—the attorney general—has the right to sue for fraud. “He has a very creative legal argument,” says Ed Morrison, a Columbia Law professor, “but the hoops he has to jump through to make it a credible case are very large challenges.”

Going to court, however, was almost beside the point; Cuomo pressed his case in the court of public opinion. He blasted “unwarranted and outrageous” company junkets at AIG, which created headlines just weeks after the government rescued the company with an $85 billion loan. Cuomo threatened to sue if his office didn’t get “immediate cooperation,” successfully pressing not just for an end to the junkets, but for freezing a $600 million bonus fund as well as $19 million due to its former chief executive.

During the winter, Cuomo and his lieutenants turned much of their attention to Merrill Lynch and its disastrous merger with Bank of America. AIG was selling off assets and seemed to be behaving itself—until late one Friday night in March. Lawsky was at the bar at Bobby Van’s, a steakhouse just across the street from the stock exchange, unwinding with other attorneys from the A.G.’s office after a long day in State Supreme Court. They were worn out from arguing that Bank of America should surrender the names of the executives who’d reaped millions in bonuses even as Merrill Lynch cratered. But around 9 p.m., Lawsky got a message on his BlackBerry that startled him.

An executive at AIG had news. The company had just sent out $165 million in payments for a “retention plan” in AIG’s financial-products division, the epicenter of the company’s losses. Lawsky traded a few e-mails trying to get more details. Then he called the boss.

Why hadn’t Cuomo stopped the bonuses back in the fall when he made the deal with AIG? Critics argue that Cuomo, having already achieved the headlines he wanted, didn’t dig hard enough. Lawsky insists that’s not the case. “We didn’t miss the existence of the plan,” he says. “We certainly didn’t know about any planned payouts, and we had a very strong expectation that they were going to come to us and talk to us. We were very angry when we learned that the Fed and Treasury had cleared these payments. We were outraged.”

The attorney general’s office worked through the weekend to get back into the fray. In phone calls with company lawyers, Lawsky demanded the names of AIG bonus recipients. “On Monday we’re calling AIG saying, ‘Where’s the list?’ ” he says. “Lists don’t take long; they have all this on a spreadsheet, they know who they’re paying.” So Cuomo turned up the heat, publicly releasing a toughly worded letter to Liddy and issuing subpoenas. Obama, finding himself playing catch-up, demanded that the Treasury Department move to seize the bonuses.

Near midnight, AIG e-mailed a list—one that itemized the bonuses by size, but with no names attached. Cuomo put the information to good use. “Barney Frank is getting ready to have a hearing,” Lawsky says. “So we crank out a letter on Tuesday that lays out some of this new information: The top guy got $6.4 million, the next four guys got $4.6, all the way down. And then he has his hearing, and after that is when it gets very hot.”

On Wednesday, Cuomo’s campaign got a weighty boost: A State Supreme Court judge ordered Bank of America to surrender the identities of its bonus recipients. AIG knew that it would be next.

But as the House was passing an overreaching bill that would tax bailout bonuses at 90 percent, Cuomo was quietly showing how much he’d learned, that now he knew when to change course and ease up. On Friday, AIG’s chief operating officer, Gerry Pasciucco, sent out an e-mail setting a 5 p.m. Monday deadline for staffers to say whether they planned to return their retention payments. Implicit in the message was something of a Cuomo ultimatum. “We have received assurances from Attorney General Cuomo that no names will be released by his office before he completes a security review,” Pasciucco wrote. “To the extent that we meet certain participation targets, it is not expected that the names would be released at all.” On Monday, Cuomo announced he’d persuaded nine of AIG’s top ten bonus recipients to give back their cash. All told, he recovered $50 million.

“Cuomo is pursuing the course the majority of voters want him to pursue, which is to recover bonuses. Are there brass knuckles being used? Yes.”

Lawsky insists that Cuomo wanted the names only to buttress his legal case. “We want to go one by one and say, ‘Okay, Person Z, you gave them $1 million. What possible basis was there? What are they doing that’s so important?’ And for that you need the names of individuals,” he says. “The list was simply so we could do a fraudulent-conveyance investigation. That got lost in the furor that ensued.”

The argument is a bit disingenuous. Cuomo could have evaluated the job performances of financial executives while keeping their names private, but he wouldn’t have scored as many public points if he’d made that promise from the beginning. “Cuomo is probably pursuing the course that the vast majority of New York State citizen voters want him to pursue, which is to try to recover bonuses,” Coffee says. “Are there brass knuckles being used? Yes.”

Though Cuomo’s pursuit of bailout bonuses has been widely popular, some analysts worry about unintended consequences of the larger assault on executive pay. “We could end up with the worst of all combinations,” says Raghuram G. Rajan, a University of Chicago finance professor, where firms that don’t touch taxpayer money are “unrestricted and unrestrained, and attract the best people,” while those that do accept bailout funds are “better able to do business because of the government backing and the low cost of capital—yet have less-capable executives managing those greater resources.” Lawsky says Cuomo is consulting with Congress about exactly those issues, because “a lot of that is big-picture Washington reforms.” Or maybe even something a governor could tackle.

In his sparse public utterances, Cuomo says that he’s busy and happy in the job he has now. But friends just laugh when they hear it. “I don’t care what anyone tells you, including him: He’s bored with what he’s doing. The challenges are just not up to his appetites,” says one pal. “What Andrew likes about this AIG thing is that it gets press and he’s beating up on the big guys. But being the warm-up band for the big act just drives him crazy.”

Despite his protestations, Cuomo certainly seems to be lining up the pieces for a gubernatorial run. An inveterate political animal, he regularly solicits advice from strategists. “Every time he sees me, he says, ‘Am I doing what I’m supposed to be doing?’ ” George Arzt says. “I don’t know and wouldn’t tell him which companies to go after. [But] we go over some of the things he needs to be doing: Who he should be reaching out to, what group he needs to go before, what issues might be good to get into.”

Cuomo is also actively fund-raising. His pursuit of AIG and Bank of America has antagonized much of Wall Street, but the old sources of financial-industry political donations are hurting anyway. Fortunately, Cuomo counts among his friends private-equity and real-estate moguls who seem to be holding up just fine. Among these backers is Andrew Farkas, who gave Cuomo a job after he’d left HUD, and steered $800,000 toward his run for A.G. “All the smart money is going to Andrew already,” one Democratic insider says. “You’ll see it in the next fund-raising filing, the shift to Andrew from David. Andrew is viewed as the governor already.”

Privately, Cuomo insists there is no way he’ll run for governor in 2010 if Paterson is in the race; he’s learned his lesson about jumping the Democratic line, and he’s worked hard to mend fences after his 2002 confrontation with black leaders. But with Paterson plunging in the polls, Cuomo is doing everything he can to nudge the incumbent out of the race. In February, as Paterson was taking a beating over the messy selection of Kirsten Gillibrand for the open Senate seat, Cuomo accepted an invitation to speak to the state Conservative Party—a gratuitous show of bi-partisan strength. “Andrew is getting a little cute,” an Albany insider says. “It’s so Machiavellian; it’s the old Andrew emerging.”

In March, Cuomo hired fund-raiser Cindy Darrison, an ace who raised millions for Spitzer and the state Democratic Party. She’d recently been pushed out by Paterson, in the latest reshuffling of his campaign team. Hiring her, says a longtime Cuomo associate, was “a mental fuck-you to the Paterson people. It doesn’t matter whether she can raise a penny; this is just Andrew’s way of sending a message. And he’ll have other people saying, ‘I don’t know how Paterson can make it.’ ”

Coincidentally, unnamed Democratic players were recently quoted in the Daily News saying that Paterson has to turn things around by November or they’ll give up on him. That same day in the Post, a Cuomo spokesman kept the drums beating by criticizing the state’s recent budget deal, edging ever closer to a direct assault on Paterson. “Andrew sees all of these different pieces, and he’s orchestrating all of it at the same time, to construct the conclusion that Paterson shouldn’t run,” the Cuomo associate says. “That’s his endgame: that Paterson shouldn’t and can’t run. He does it indirectly and with sleight of hand, because that’s what Andrew knows best.”

He seems to be at the top of his game—actually, multiple games. He’s moving his political rival aside while feigning uninterest in the governor’s job, and positioning himself as a champion of the taxpaying masses as he lines up campaign money from business titans. He has been very good, but he’s also been very lucky. It’s a combination that state government hasn’t seen in a very long time. But Andrew Cuomo knows better than anyone how quickly the game can change.