Last August, shortly after his arrival at the federal correctional complex in Butner, North Carolina, Bernard L. Madoff was waiting on the evening pill line for his blood-pressure medication when he heard another inmate call his name. Madoff, then 71, author of the most devastating Ponzi scheme in history, was dressed like every other prisoner, in one of his three pairs of standard-issue khakis, his name and inmate number glued over the shirt pocket. Rec time, the best part of a prisoner’s day, was drawing to a close, and Madoff, who liked to walk the gravel track, sometimes with Carmine Persico, the former mob boss, or Jonathan Pollard, the spy, had hurried to the infirmary, passing the solitary housing unit—the hole—ducking through the gym and the twelve-foot-high fence and turning in the direction of Maryland, the unit where child molesters are confined after they’ve served their sentences. As usual, the med line was long and moved slowly. There were a hundred prisoners, some standing outside in the heat, waiting for one nurse.

Madoff was accustomed to hearing other inmates call his name. From July 14, the day he arrived, he’d been an object of fascination. Prisoners had assiduously followed his criminal career on the prison TVs. “Hey, Bernie,” an inmate would yell to him admiringly while he was at his job sweeping up the cafeteria, “I seen you on TV.” In return, Madoff nodded and waved, smiling that sphinxlike half-smile. “What did he say?” Madoff sometimes asked.

But that evening an inmate badgered Madoff about the victims of his $65 billion scheme, and kept at it. According to K. C. White, a bank robber and prison artist who escorted a sick friend that evening, Madoff stopped smiling and got angry. “Fuck my victims,” he said, loud enough for other inmates to hear. “I carried them for twenty years, and now I’m doing 150 years.”

For Bernie Madoff, living a lie had once been a full-time job, which carried with it a constant, nagging anxiety. “It was a nightmare for me,” he told investigators, using the word over and over, as if he were the real victim. “I wish they caught me six years ago, eight years ago,” he said in a little-noticed interview with them.

And so prison offered Madoff a measure of relief. Even his first stop, the hellhole of Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC), where he was locked down 23 hours a day, was a kind of asylum. He no longer had to fear the knock on the door that would signal “the jig was up,” as he put it. And he no longer had to express what he didn’t feel. Bernie could be himself. Pollard’s former cellmate John Bowler recalls a conversation between Pollard and Madoff: “Bernie was telling a story about an old lady. She was bugging him for her money, so he said to her, ‘Here’s your money,’ and gave her a check. When she saw the amount she says, ‘That’s unbelievable,’ and she says, ‘Take it back.’ And urged her friends [to invest].”

Pollard thought that taking advantage of old ladies was “kind of fucked up.”

“Well, that’s what I did,” Madoff said matter-of-factly.

“You are going to pay with God,” Pollard warned.

Madoff was unmoved. He was past apologizing. In prison, he crafted his own version of events. From MCC, Madoff explained the trap he was in. “People just kept throwing money at me,” Madoff related to a prison consultant who advised him on how to endure prison life. “Some guy wanted to invest, and if I said no, the guy said, ‘What, I’m not good enough?’ ” One day, Shannon Hay, a drug dealer who lived in the same unit in Butner as Madoff, asked about his crimes. “He told me his side. He took money off of people who were rich and greedy and wanted more,” says Hay, who was released in December. People, in other words, who deserved it.

There is, as it happens, honor among thieves, a fact that worked mostly to Madoff’s benefit. In the context of prison, he isn’t a cancer on society; he’s a success, admired for his vast accomplishments. “A hero,” wrote Robert Rosso, a lifer, on a website he managed to found called convictinc .com. “He’s arguably the greatest con of all time.”

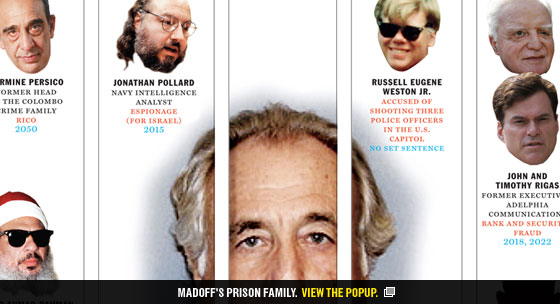

From the day Bernard Lawrence Madoff, prisoner No. 61727-054, arrived at the softer of Butner’s two medium-security facilities in handcuffs and shackles, his over-the-collar hair shorn close, his rich man’s paunch diminished, he was a celebrity, even if his admirers were now murderers and sex offenders. The Butner correctional complex, which includes four prisons and a medical center, already has its share of crime kings. Pollard, the Israel cause célèbre who spied for the Jewish homeland, lived in Madoff’s housing unit, Clemson (the dorms are named after Atlantic Coast Conference colleges). Persico, the former Colombo-family godfather, lives in nearby Georgia Tech. Omar Ahmad-Rahman, the blind sheikh who helped engineer the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, is in Butner. The Rigases from Pennsylvania, the father and son who bankrupted Adelphia Communications Corporation, are there—they wear crisp, pressed uniforms, which inmates assume they pay others to maintain.

Yet even in this crowd, Madoff stands out. Every inmate remembers the day he arrived. “It was like the president was visiting,” a visitor to Butner that day told me. News helicopters buzzed overhead, and the administration locked down part of the prison, confining some inmates to their units, while an aging con man with high blood pressure shuffled through processing, where other inmates fitted him for a uniform and offered a brief orientation: “Man, chill out and go with the flow, ” was the advice of one former drug dealer.

Quickly, the flow came to Madoff. From the moment he alighted, he had “groupies,” according to several inmates. Prisoners trailed him as he took his exercise around the track. (Persico had also attracted a throng when he arrived, but was disgusted and quickly put an end to it.) “They buttered him up,” one former inmate told me. “Everybody was trying to kiss his ass,” says Shawn Evans, who spent 28 months in Butner. They even clamored for his autograph.

And Madoff was usually more than happy to respond. “He enjoyed being a celebrity,” says Nancy Fineman, an attorney to whom Madoff granted an interview shortly after his arrival at Butner. (Fineman represents victims who are suing some of Madoff’s “aiders and abettors,” as she calls them.) Madoff seemed surprised and tickled by the lavish treatment, though he steadfastly refused to sign anything. Even in prison, he wasn’t going to dilute the brand. “He was sure they would sell it on eBay,” Fineman told me. “He still did have a big ego.”

Remarkably, that ego appears to have survived intact. H. David Kotz, the Security and Exchange Commission’s inspector general, investigated his agency’s failure to uncover Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, and Madoff volunteered to speak to him—he is, no doubt, the world’s expert on the subject. He quickly reminded Kotz of his stature—“I wrote a good portion of the rules when it comes to trading,” Madoff said. He insisted that he’d been “a good trader” with a solid strategy, explaining that he’d stumbled into trouble because of his success. Hedge funds—“just marketers,” he said with evident disgust—pushed cash on him. He overcommitted, got behind, and generated a few imaginary trades, figuring he’d make it up—and never did. Whatever his own missteps, Madoff saved his scorn for the SEC. He did impressions of its agents, leaning back with his hands behind his head just as one self-serious agent did—“a guy who comes on like he’s Columbo,” but who was “an idiot,” Madoff said, as recorded in the extraordinary exhibit 104, a twelve-page account of the interview that is part of Kotz’s report. Madoff is no ironist. His disdain for the SEC is professional, even if the agency’s incompetence saved his skin for years—all Columbo had to do was make one phone call. “[It’s] accounting 101,” Madoff told Kotz, still amazed.

Madoff’s ego was on display in prison, too. “Bernie walked around prison confident,” says ex-con Keith Mack, adding, with a trace of resentment, “he acted like he beat the world.” And to most inmates he had. Many—and I communicated with more than two dozen current and recent Butner inmates (though not Madoff)—can recount stories of his conquests, a good number of them related by Madoff himself. “He said something to me one day,” recalls an ex–drug trafficker, released in February. “He could spin the globe and stop it anywhere with his finger, and chances are he had a house there or he’d been there. I was pretty blown away.” One evening, Bowler, a drug trafficker (“I’m not a con man, I’m a businessman,” he wrote to me), sat next to Madoff watching a 60 Minutes segment about him. Prison authorities keep the volume off, and inmates wear headphones and tune in to the radio signal that broadcasts the sound. Bowler removed one earpiece. “ ‘Bernie, you got ’em for millions,’ I said to him. ‘No, billions,’ he told me.” Another evening, one former inmate was watching a TV news report on the auction of Madoff’s much-chronicled watch collection—he owned more than 40, from Rolexes to a Piaget. The watch featured that evening fetched just $900, and Madoff, whose only watch now is a Timex Ironman that he bought at the commissary for $41.65 and is likely engraved with his inmate number, called out, “They told me that watch was worth $200,000.” The inmates laughed along with him. They didn’t see any reason for Madoff to regret his past. “If I’d lived that well for 70 years, I wouldn’t care that I ended up in prison,” Evans says.

Inmates were impressed by the sheer scale of Madoff’s operation and turned to him for guidance in getting their own ambitions on track. Madoff had always enjoyed being counselor to the wealthy and powerful. That had been part of the scheme’s seduction: Bernie, the scrappy kid from Queens, depended on by rich businessmen. “He wants to be remembered as a titan of Wall Street,” says Fineman, and one who subsidized the private schools and fancy vacations of his wealthy friends, even if it was with the funds of other investors. And to inmates he still was a titan.

Illustration by K.C. White

Prisoners crowded Madoff seeking investment advice—missing the fact that Madoff, being a con man, hadn’t invested for years. Other convicts saw in him a fellow entrepreneur, ignoring the obvious fact that his scheme wasn’t a business at all, just smoke and mirrors. But Madoff had amassed the symbols of success, and for criminals, that counts. They are an ambitious, if not always perceptive, lot—you can’t sleep all day and night and still be a drug lord. “They all have dreams of going home, starting businesses, and buying new cars and homes,” one inmate wrote me. One day, a guy known as Barkley trotted after Madoff, unusual in and of itself because prisoners aren’t allowed to run. Evans, nicknamed Solo (“because that’s how I roll,” he told me), watched the scene unfold. He remembers that another inmate yelled out as a joke, “Put that knife away.” When Barkley caught up to Madoff, he reacted as if he were being mugged and held out his commissary bag, ready to surrender it. But Barkley just wanted advice. “The guy was into real estate when he was out, and he wanted to ask the man some financial questions,” Solo told me by phone from Mississippi, and laughed.

But if Madoff was a respected financial adviser, he was also a mark. “People are not going to befriend you unless there is something in it for them,” one former inmate told me. With Madoff, some had an angle. “People were trying to get up under him,” says one ex-con. After all, everyone believes that an operator as cunning as Madoff must have a stash somewhere, and they also believe that, prisoner to prisoner, he might confide its whereabouts. “Where did you hide it?” White asked him one day while walking the track together. “It’s H20,” Madoff told White, making a gesture of water slipping through his hand.

Not all prisoners are part of the Bernie Madoff fan club. “You an inmate, not a convict,” Bowler needled him, pointing out, “You got less than a year in the bucket,” meaning he’d only just arrived in prison. That he isn’t a rat—he’s tried to take all the blame for his Ponzi scheme—and isn’t a child molester counts in his favor. But Madoff isn’t seasoned or tough. “He didn’t know how to take a shower,” says Bowler, now confined in a Lexington, Kentucky, facility. (At Butner, you don’t get undressed until in the shower itself.) He has a reputation for messiness, which isn’t respectful to a cellmate. “He wasn’t prison material,” says one ex-con dismissively. Madoff seemed helpless to some. This former inmate had given himself tattoos with a device he built from a beard trimmer, a toothbrush, and a Bic pen—“A real con can jerry-rig anything,” Bowler told me.

Fortunately for Madoff, he’d landed at Butner Medium I, “Camp Fluffy,” as those who’d experienced other prisons call it. Medium I, population 758, is filled with “soft” prisoners, those who might not survive other institutions, including pedophiles and cooperators (“rats”). The facility had been planned during a brief period of penal optimism and was designed to humanize the prison experience. The physical space resembles a campus, with landscaped yards and hedges shaped by inmates into giant globes. “There’s flowers and trees; you can lay out on the grass and tan,” an ex-inmate told me with a laugh. “There’s no bars. There are windows.” There’s a gym, a library, pool tables, a chapel, a volleyball court, and an Indian sweat lodge.

But however soft, prison is a hardship. And on his way to Butner, Madoff opened up to Herb Hoelter, the prison consultant known for helping ease celebrity prisoners onto their new paths—he’d previously worked with Martha Stewart.

“What do I do with my life now?” Madoff asked Hoelter.

That’s the existential challenge of prison, especially for someone with a life sentence. And there aren’t obvious answers. There’s little meaningful to do—nothing “aspirational,” as a tax evader who’d served time in Butner complained. Free will is limited. “You sleep and eat and shit and shower when they tell you to,” a recent Butner releasee told me. Freedom, such as it is, is in the mind. “It’s your ability to think that’s not circumscribed,” explains Art Beeler, the warden until last year. But Madoff has never been an intellectual—he has the mentality of “an auto mechanic,” one hedge-fund manager told me. He keeps it simple, and it works. And so in prison, “Bernie adjusted better than I did,” says Hay, who slept a few doors down from Madoff. “He didn’t seem like he had any worry or stressed too much or had nerve or panic attacks, like I did. Going from an $8 million house”—his penthouse on East 64th Street—“to an eight-by-ten cell, I would feel smothered. Bernie never complained that I heard.”

At Butner, Madoff got busy lining up a new set of creature comforts, such as they were. He hired an inmate to do his laundry for $8 a month, Bowler says. “That was my hustle,” which is what prisoners call their side job, Bowler tells me. “I was charging $10, which is the going rate, but Bernie’s too cheap.” Once a week, Madoff takes his place on the commissary line, turning in his checklist of goodies to buy—“All sales are final,” it says on the sheet. An inmate can spend only $290 a month, but prices are reasonable. A radio goes for as little as $17.95, earplugs for 40 cents, sweatpants $18.85, and food is cheap: Macaroni and cheese, one of Madoff’s favorite meals, costs 60 cents, and a can of Madoff’s preferred drink, Diet Coke, is a bargain at 45 cents.

“Bernie never wanted for anything,” says Hay. Madoff’s lifestyle may have been turned on its head, but he adapted, a con man’s skill. He has, it turns out, a knack for thrift, a throwback perhaps to his less regal days in Queens. “You couldn’t get an ice-cream cone off him,” says Bowler. Another ex-inmate calls him “stingy.” He bought the necessities, a radio and headphones, jogging shorts, and that Timex watch. And he laid in provisions, snacks and food, storing them in the locker in his cell (you can buy a combination lock at the commissary for $6.25).

He receives a couple of newspaper subscriptions via the mail. Sometimes he relaxes atop a picnic bench bolted to a concrete terrace outside his unit, his arm folded over his eyes, or else he reads. Madoff likes crime mysteries by Dean Koontz and John Grisham, which he also receives in the mail, reads avidly, and then passes along. For a break, there is gambling, with the odds coming out of Vegas. Madoff has been seen with betting slips.

And Madoff threw himself into the prison-work world, applying for jobs as energetically as a new college grad. Madoff told Fineman that because of his age, he wasn’t obligated to work, but how else to fill the time? He’d always been industrious—keeping the con going was a continual hustle—and initially he’d hoped for a spot on the prison-landscaping crew. He proposed that he serve as the clerk in charge of budget. He had qualifications—he’d been chairman of NASDAQ. “Hell, no,” said the supervisor to Evans, laughing. “I do my own budget. I know what he did on the outside.” In an August 13 call-out sheet, which lists prisoners’ daily assignments, Madoff’s is maintenance. He gave out paint. Later, he was assigned to the cafeteria, where he walked around with a dustpan and broom, sweeping up dropped food for 14 cents an hour, the wage earned by new arrivals.

Prison is a tribal society, and people stick with their own. Some are loyal to their state of origin—there’s a Florida “car,” as any grouping of inmates is called, and a New York car. Or they segregate by race. “Even here in the low-security prison,” which is even less rugged than Medium I—“blacks hate whites and whites hate blacks; that’s just the way it is,” a convicted murderer wrote to me. Italians like Persico have their own car. Often Persico could be seen with Rosso, the founder of convictinc.com, and John Conza, a counterfeiter from New York, and, when he was there, Joseph Testa, the Brooklyn-based Gambino family member who was one of the mob’s most prolific murderers.

Some inmates organize themselves by “bid,” their sentence, and Madoff associated with a group that half-jokingly referred to itself as “the lifers gang.” Pollard the spy is a ringleader—though he has a release date, he’d been an inmate most of his adult life and so apparently qualified. “He kept everybody rolling,” says Hay, who sat with the group despite his shorter sentence. Pollard, now 55 years old, heavier and balder than when he was sentenced in 1987, wears a yarmulke everywhere—sold in the commissary for $2.60. Pollard is a hero to the Israeli right wing, which had pressed Bill Clinton and George W. Bush to pardon him. But at the chow table, Pollard is the group’s griot, a folklorist of prison life who entertains with ghoulish tales of past inmates, shocking even longtime cons. “He remembered one guy was mental and took a nurse hostage at Butner,” says Hay. “Outside, he’d abducted a bus full of children.” The kids were found dead. As a kind of punch line, Pollard added “retarded children.” Gary Karr, 62 and with a life sentence, is another participant in the lifers gang, and was Pollard’s cellmate at one point. He was believed to have been involved in carving up a couple of people in Texas, though inmates don’t usually hold a man’s crime against him. “Gary was right down good-hearted. I never knowed him to have a problem with anybody,” says Hay. Lee Summers, whose sentence runs through 2020, hangs around with them, too, as does Stephan Bullis, another lifer, who sent a bomb to his wife’s office, blowing off most of her left hand.

At the cafeteria, Madoff sometimes ate with a guy nicknamed Muscles, an obsessive-compulsive fellow who takes half an hour to make his bed—Madoff must have empathized, since he’s famously compulsive himself. Pollard, a cutup, kidded Madoff about how much time they got. Pollard was loose and comical—“always happy,” one con tells me—and liked to work blue. Hay recalls, “They brought a young boy in for evaluation. He was small. I said to him, ‘Hey, boy, you got to be 18 to drink coffee.’ ” Pollard chimed in, “ ‘Yeah, but you’re old enough to suck all the dick you want.’ Pollard is a good-hearted guy.”

Gay inmates form another tribe. There are perhaps a couple dozen openly gay inmates in Clemson—straight prisoners continually conduct a census—and then secret ones who are gossiped about on inmate.com, as some call the grapevine. Gay inmates stick together, too; the lifers gang follows their goings-on with outward disgust and rapt attention. How much is it for a blow job? Three books of stamps, they were told, which raised a howl. (Inmates aren’t permitted to touch money, so stamps are prison currency; a book worth $8.80 at the commissary goes for $6 in the yard.) Much of the prison’s sexual drama swirls around the gay population. Inmates told and retold the story of Yolonda Burt, a preoperative transsexual in Medium I who had been stabbed in what was described as a lovers’ spat. Yolonda wrote me her view: “On November 7, 2009, around 8 a.m., an inmate attempted to rape me, and when I refused him, he cut me with a box cutter. On 12-28-09, he killed himself in the hole.” By hanging, as Hay tells the story.

Madoff enjoys the soap opera as much as anyone. But he seems to float above the prison’s hierarchies, as befits a celebrity. Early in his stay, Madoff sat on the boccie-ball court with Persico—they’re not as close now. He’s comfortable with black inmates, too, talking, mingling, occasionally even joking with some of them: “Why are you always picking on the white man?” His cellmate at one point was a black drug dealer, and they got along. And Madoff posed for White, the prison artist, who’s black. Madoff even signed the sketch, breaking his rule, says White, who secretly wrote on Madoff’s collar: FUCK MY VICTIMS.

Gay prisoners don’t offend Madoff, who is, after all, a sophisticated New Yorker. One evening on his way through the day room Madoff griped to the lifers gang, “All you guys talk about is ‘Queer this, queer that.’ Don’t you have anything better to talk about?” Madoff had been kind enough to advise Yolonda on how to raise money for her sex-change operation. He was even friendly toward a detested child molester—a cho-mo, as they’re called. Marvin Hersh, serving 105 years, was known by some in prison as the “Florida Monster.” He’s a former professor who took a Central American teenager into his home, cared for him like a father, and molested him several times a week. Madoff played Scrabble with Hersh in the TV room. Madoff’s social promiscuity, so unlike a veteran con, confused and irked some. “I started the rumor Bernie was a switch-hitter,” says Bowler, who thought it good fun.

Mealtime is a much-anticipated break in the prison day, one of a few pauses in a tightly enforced schedule. “Food is a very big thing in prison,” says Conza. “You could sit down with your friends.” At mealtime, tribes seek their own. In the chow hall, Carmine Persico almost always sat at the same table with Conza (now out) and Rosso and a fourth, sending one guy ahead to reserve it. “No one ever sat at Carmine’s table,” says one ex-con. “Out of respect.”

Persico also liked to use a microwave to cook for himself and his friends. “Carmine made the best spaghetti and white clam sauce I ever had,” says Conza, who was Persico’s cellmate for about a year. “He was an unbelievable microwave chef.” Inmates buy the basics from the commissary, then add vegetables stolen from the kitchen—an onion costs five stamps.

The lifers gang had its own eating club, and Madoff sometimes joined in. For Hay’s going-away party, Pollard microwaved a pizza—a pizza kit costs $3.20 at the commissary. Madoff was there, and Pollard kidded him about putting on weight.

Life at Butner was pleasant, at least by prison standards, and yet in prison, danger is like static electricity, always in the air. Inmates aren’t known for their anger-management skills, one reason they are often exaggeratedly polite. “You’ve got to be careful not to insult anyone,” says one former Butner inmate, who has a law degree, “and everyone is waiting to be insulted.” As another former Butner inmate told me by phone, “Everybody is trying to do somebody in.”

Madoff had reportedly gotten into a scrape in December, according to the Wall Street Journal, and was taken to the prison hospital with fractured ribs and a broken nose. Madoff’s doings are big news on inmate.com, and every inmate seems to have his own version of the event. One held that the attack on Madoff was a reprimand. “He was arrogant,” one inmate reported. But Madoff insisted to his friends that he’d merely received the wrong medication. It made him light-headed, and he’d fallen. Those closest to Madoff believe him. “If Bernie had gotten beat up, I would have done something about it,” says one well-built New York con, who considered Madoff a member of his car. (The prison administration denies that Madoff was assaulted, as does his attorney.) Certainly inmates have reason to keep a fight quiet. Madoff knew that anyone involved in a fight, even a victim, can end up in “the shu,” as inmates call the hole—locked down for 23 hours a day, which makes regular prison life seem airy and fun.

Whatever happened, Madoff continues in his routines, seeking what small pleasures he can, and not revealing much. Over time, as his celebrity wore off, even inmates who lived close to him noticed that Madoff could be opaque and hard to read. He speaks when spoken to and sometimes stares off in the distance. At night, he paces the halls. Maybe it’s shyness; Madoff had long been socially remote, even at the Palm Beach Country Club, where he met a swath of his victims. “Maybe he’s the type to cry under his blanket,” one inmate who lived near Madoff told me. But there is at least one thing that troubles Madoff, and inmates tuned into this. Prisoners are shut off from loved ones—one seasoned ex-con lamented to me that he’d missed his nephew’s funeral and his son’s graduation. Madoff had been his family’s patriarch. His two sons, his brother, and his brother’s daughter had once earned a very nice living from Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, Madoff’s legitimate and very successful market-making business. Even in prison Madoff continues to think of himself as a family man. One day Hay told Madoff that if positions had been reversed, he would have fled: “If I had your money, I’d have been out of the country with a face change and everything else.”

Madoff waved him off. “I’ve got family,” he responded. He didn’t elaborate with Hay, but with lawyers he was more open. After all, no one knew Madoff better or, in a sense, cared more about him than the attorneys who sued him—they were part of his car. To them, Madoff dropped hints of the pangs he felt. Fineman recalls that while she focused on his Ponzi scheme, Madoff talked at length about his wife, Ruth. It was the only time in their four and a half hours together that Fineman felt any sympathy for him. Ruth and Bernie had been teenage sweethearts, and Madoff told Fineman the story of their meeting in high school, an innocent time when he was on the swim team and she was a popular, outgoing, fifties-style preppy. Fineman says, “He talked about how he’d gone off to college. He just missed her. So he moved back to New York. His voice had a different tone when he talked about her. It was the one time he was emotional.” Madoff’s sons are no longer a presence in his life—they’re still in legal jeopardy and have been counseled to cease communication with their father.

Ruth, though, sticks by him. “She was distraught and upset,” Hoelter was told. And though she’s no longer being pursued criminally, she’s ruined, too—at one point, she had to report every expenditure over $100 to a bankruptcy trustee.

Ruth visited Madoff at Butner. Returning to his cell after one visit, he reported wistfully, “She’s off to play golf,” something they’d loved to do together. Inmates sensed his attachment and “aggravated” him about it, as one told me. They’d seen pictures of Ruth in the media. She’s still a pert, smiling blonde who they assume is considerably younger than Madoff—another one of his trophies. (Madoff didn’t disabuse them of the notion, though she’s only three years his junior.) “I’m getting out, and I’ll keep her company,” they’d kid Madoff. Pollard, Madoff’s friend, rode him, too; Madoff better eat right and stay in shape. “You’ve got that young wife,” Hay added. Madoff laughs at the jokes. But he’s a realist. Despite the illusionary world he’d created, he always had been. “I got 150 years and I’m 71,” he responded. “I’m not worried about getting out of shape.”

Additional research by Sam Dangremond.