There was no fire yet, not up here, but there was smoke. The six men sent to the fourth floor of the tenement couldn’t see more than a few inches in front of them. There was heat too. They could feel it and see it on the screen of a handheld thermal-imaging camera, surging behind a wall.

The call had come at 7:59 on a Sunday morning, the day after a January blizzard had shut down the city. There was still more than a foot of unplowed snow on East 178th Street off the Grand Concourse, and some of it was still swirling in 45-mile-an-hour gusts. Wind like that has a habit of working like gasoline on even the tiniest fires. Five trucks from five companies inched through the snow to converge on the tenement, a cookie-cutter version of thousands of other old buildings in the South Bronx. Engine 42 got there first; its men were stretching hoses from their truck and running them upstairs. Ladder 33 got there next, and a number of its men were sent to the third floor, where the fire was burning. The firefighters from Ladder 27 and Rescue 3 had arrived next; they were sent to the floor above the fire to clear it and keep the flames from spreading upward.

When the six men got to the fourth floor, they started searching from apartment to apartment, but they’d found no civilians (except the skinny guy and naked fat lady one of the guys saw hightailing it out of there just as they came up the stairs). Now they were in Apartment 4-L, feeling their way along the walls from room to room—six men loaded down with gear, sucking in air from their tanks—and soon they got turned around, lost in the smoke. Brendan Cawley, the probie with just a month on the job, kept seeing padlocks on the doors of every room and was confused; he hadn’t been around long enough to know how many apartments in this neighborhood had been converted into cheap, crowded rooming houses. This place had been chopped up, probably illegally. Random walls and carelessly thrown-up partitions created a maze. The men were trying to make their way to the source of the heat surge, but among the locks and the walls and the smoke, they couldn’t seem to get there. And there was another problem: The men didn’t have working hoses. First, there was a frozen hydrant; then, something seemed wrong with some of the hoses themselves. The six men on the fourth floor couldn’t fight a fire they couldn’t find—and if any fire did come, they had nothing to fight it with.

At 8:26 a.m., Curt Meyran, the lieutenant in charge of the Ladder 27 crew, checked in on his radio. He was asked about the status of the fire on the fourth floor. “Slight extension, slight extension,” Meyran said—meaning they still saw just smoke, no fire.

“Ten-four,” came the response.

Somewhere between 18 and 23 seconds later—still 8:26 a.m., maybe even as the responder was talking—a turret of flame roared up though the floorboards. None of them saw it coming—in an instant, all six were pinned against the windows that faced the back. “We need a line on the floor above,” someone barked into the radio. “We have heavy fire on the floor above. Rescue to Battalion. Urgent.”

In the background, another voice—no one’s sure whose—could be heard: “We got no water!”

The flames formed a wall between the men and the apartment door. Walking out was no longer an option. Meyran called in a Mayday and he and Gene Stolowski and Cawley stuck their heads outside for air. At the windows next to them were two guys from Rescue 3, Jeff Cool and Joe DiBernardo. They had lost track of the sixth man, John Bellew. It was 17 degrees outside, but even as their faces were freezing, the men felt a scorching heat on their backs. Leaning out, they could see a fire escape two windows away—but it was too far for them to jump.

Meyran called in a Mayday at 8:29. Seconds later, DiBernardo radioed an outfit on the roof: “Brothers on the roof, you’re gonna need to send a rope over the side. Roof team—send a rope over the side to the two-four side of the building.”

The flames were closer now. Jeff Cool could feel them at his neck. Cool had a wife and two kids. Meyran had a wife and three kids. Bellew had a wife and four kids. Stolowski had a daughter, and his wife was expecting twin girls in June. DiBernardo’s dad was a retired deputy fire chief. Cawley had an older brother who had died on 9/11.

Then came the transmissions:

8:30:43: “Mayday! Mayday 56! Man down, fell out the window!”

8:30:48: “Mayday! Mayday!”

8:30:49: “Fireman down in the rear! Two firemen down in the rear!”

8:30:51: “Two firemen down in the rear—let’s go!”

8:30:54: “Seventy-five, put your pumps…”

8:30:58: “Mayday! Mayday! Two firemen jumped from the top floor in the rear. We need a…”

8:31:09: “Brother in the…”

“Oh, man!”

8:31:15: “Start a mixer off—we got a whole company in the rear, they had to jump.”

8:31:23: “No way, no…”

“We got six guys…”

8:31:35: “Roof, let the rope down!”

8:31:40: “Mayday! Mayday in the rear! We need EMS in the rear.”

8:32:20: “One, two, three, four, five, six who jumped in the rear! We need massive EMS here! Massive injuries!”

On the morning of January 23, 2005, six firefighters jumped out of four fourth-story windows of a tenement at 236 East 178th Street in the Bronx, falling 50 feet to the pavement. Two of them, Curt Meyran and John Bellew, died from their injuries; another four—Gene Stolowski, Brendan Cawley, Joe DiBernardo, and Jeff Cool—barely survived, sustaining massive injuries of their own that left several of them in the hospital for months and effectively ended their careers. Another firefighter, Richard Sclafani, died at an unrelated fire in Brooklyn that same afternoon, making that day the first since 1918 that men had died in two separate incidents in the city; the dual tragedies have come to be known as Black Sunday.

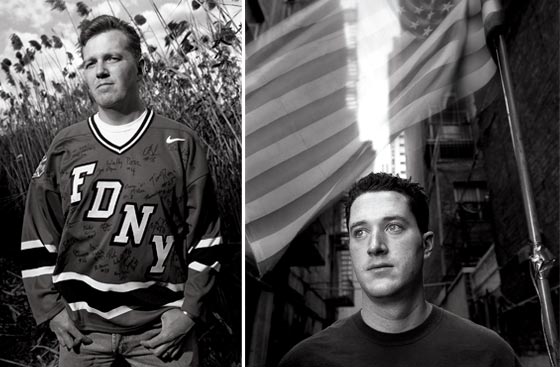

Now the surviving firefighters are telling their version of the story for the first time. To date, the men have spoken publicly only briefly, but because of litigation they’ve filed against the city, they’ve avoided giving a full account of what happened that day. In the past few months, however, the four of them have begun appearing at private firefighter gatherings to tell their story, and three of them sat with New York Magazine for their first extensive interviews, speaking out about controversies that have surrounded the fire for two years. Shouldn’t the department have outfitted the firefighters with personal-safety ropes—a piece of equipment that was once standard issue but was not provided at the time? Is the building’s landlord primarily to blame, for blocking off access to the fire escape with an illegal subdivision? Should the department have kept the six men on the fourth floor that long, given the problems with the hydrants and hoses? Or were the men themselves in part at fault for not making their situation clear to the officers on the ground? The survivors’ stories also reveal for the first time something much more personal: just how deeply the tragedy has affected them and their families. Their lives—once centered around straightforward concepts like action and adrenaline, honor and bravery—are more complicated than they once were. They are heroes, but they are lost.

It took the Ladder 27 crew longer than they expected—about six minutes—to make it just ten blocks. The blizzard was part of the problem, as was a double-parked truck on East Tremont Avenue. It didn’t help that they had the wrong address, though that was quickly corrected. When Gene Stolowski saw Engine 42 and Ladder 33 stretching hoses up to the third floor of the building, he knew this one was real. “I think we got something,” he told Brendan Cawley. “Let’s go.”

Curt Meyran, Stolowski, and Cawley walked into the front entryway, a wide foyer where they saw the first signs of smoke (John Bellew, the driver, came up a few minutes later). Up they marched, passing the guys from Ladder 33 on the third floor. But already, things had started going wrong.

At 8:05 a.m., about the same time that Ladder 27 had arrived, the driver from Engine 42 had reported the frozen hydrant. Outside, firefighters hustled to connect hoses to a booster tank on their truck, while others stretched hoses to hydrants farther away. For a moment, the third floor got water back, then lost it again; then the water came back but the pressure was too weak and the nozzle would shut. Now the hoses seemed to be frozen or ruptured: No one knew which. Without water, the fire was spreading unchecked.

When the Ladder 27 crew reached the fourth floor, Meyran told Stolowski to prop open the stairway door with his maul. Meyran, Stolowski, and Cawley slipped on their oxygen masks and walked into Apartment 4-L. Everything was pitch-black—no lights, no windows, nothing but smoke. Clothes and furniture were everywhere. Cawley had to feel his way around so he wouldn’t trip. In one of the bedrooms, he ran into another firefighter, knocking him to the floor; he looked at the uniform and saw a number three. He later guessed it was Jeff Cool, who’d made it upstairs with Joe DiBernardo and others from Rescue 3.

Ten minutes passed as the six men from the two units did their job. The hoses still weren’t working, but they weren’t worried yet. “We’re thinking, The fire’s going out,” Stolowski remembers. “We’re thinking, This is a routine fire.” And after they smashed open a few windows in several bedrooms, the smoke began to clear, making the situation seem less urgent.

It was then that Meyran learned that the water wasn’t coming anytime soon. “We need to find a secondary means of egress,” he told Cawley. Cawley had already told him that he’d identified a fire escape. He and Meyran started feeling along the wall, trying to get to the hallway that led to it. But they were interrupted when the vibrating alert on their oxygen tanks went off. They each had just a quarter-tank left—enough in most cases to get out of a building. “Let’s go,” Meyran said.

They were on their way back to the stairwell when they spotted Stolowski, who had been in the next bedroom. His tank was already empty, and he’d pulled off his mask. They hustled Stolowski to a window, outside of which a team of firefighters on the roof had dangled a mask and supplemental oxygen tank. Meyran stood at the window. Stolowski, who was next to him with Cawley, had pulled the mask in and was on his knees, gulping air. “What I had planned on is, we’ll all take breaths and just walk out of the apartment,” Stolowski says. “Meyran had asked Brendan to take his mask off. I was going to give him the mask. That’s when the heat hit him.”

They didn’t see the fire as much as feel it. Cawley describes it as a wave of heat that smacked him in the head. Suddenly the probie was hearing Meyran calling Mayday. “I’m just out of the academy,” Cawley recalls, “but I knew we were in a world of shit.”

They were trapped at the window now, the three of them. Meyran told Cawley to take off his mask to prepare him for what they knew had to happen next. They were in the back of the building, staring into an alley ten feet below street level. If they jumped, they would plunge 50 feet.

The window wasn’t big enough for three men in helmets and masks with tanks on their backs to poke their heads out. So Meyran got on all fours, straddling the window—one arm and leg inside, one arm and leg outside. Stolowski and Cawley knelt at the windowsill, leaned over Meyran’s back, and breathed. “It was unbelievable that he could even think of doing that,” Cawley says. They waited for help, but by then, they knew there was no way out but the window.

Meyran’s place at the window made him the natural choice to jump first. Cawley and Stolowski held on to Meyran as he dangled from the windowsill. Stolowski let go of Meyran first, then Cawley let go of him. The probie watched as his boss fell to the ground. Cawley was next: Stolowski grabbed him and pulled him up and over the windowsill—but kept holding the probie’s coat, lowering him as far as he could before letting him go.

By then the fire was too strong for Stolowski to finesse his exit. He jumped out the window headfirst. Dangling on a window gate for a few moments, he could see through a lower window into the third-floor. If fire blows out that window, I’m gonna get cooked, he thought. Then he fell.

Jeff Cool had been walking toward Meyran, Cawley, and Stolowski from the kitchen when the fire came. He wound up standing at a window next to the one where the three others had gathered. Sticking his head outside, Cool was waiting for a rope from above—he’d heard something on his radio about the roof men—but help never came. At the next window, one bedroom over, Cool saw Joe DiBernardo, yelling into his walkie-talkie for help. A minute later, at 8:30 a.m., the heat was too much for both men. DiBernardo radioed again. “We’re bailing out of here. Hurry up!”

Cool pulled out a safety rope—one he’d bought months earlier at a trade show. He was the only one with a rope. He called over to DiBernardo, “I have nowhere to anchor it!”

“Throw it to me,” DiBernardo said. “I’ll anchor you.”

Cool threw one end of the rope. He wanted DiBernardo to drop first, with Cool anchoring him. But DiBernardo shook his head.

“You have a wife and kids,” he said. “You go first.”

DiBernardo lowered Cool out of the window. When Cool swung over the edge, he slammed into the side of the building, knocking the wind out of him. Either the rope slipped or Cool let go—even he isn’t sure—but then Cool fell. DiBernardo tied the rope to the window, lowered himself down, and then dropped.

None of the men saw John Bellew fall. But a lieutenant who was in the backyard told Cawley that he saw Bellew climb out, hang on for a few seconds, then release, just as Curt Meyran had. “It’s kind of consoling, I guess,” says Cawley, “to know that John knew what was going on and made the decision, rather than just jumping out.”

The bodies of six firefighters now lay on the ground. When Stolowski had let Cawley go, the probie had tipped backward and started falling headfirst. “I kind of tucked my chin to my chest because I knew I was falling upside down,” he says. “I didn’t want to land on my head.” He landed on his upper back, shattering his right shoulder, cracking his ribs, splitting his skull, and collapsing a lung. He used his right arm to pull himself up to a sitting position so he could breathe easier. Then he passed out.

Stolowski caught something of a break when the top of his shoulder pack got snagged on the window guard, swinging his body around—had he fallen headfirst, he almost certainly would have died. Still, the force of the impact broke his neck. He stopped breathing, but when a firefighter administered CPR, Stolowski awoke, feeling snow on his face. His oxygen tank had kept his head from snapping so far back that he would have died.

DiBernardo landed feet first, shattering everything from his waist down. “I didn’t even feel the cold,” he would say later. “All I felt was the pain in my legs.” Cool broke both his shoulders, fractured his skull in two places, shattered his pelvis in three, and broke thirteen ribs and an arm. But he was conscious enough to talk to two firefighters who held a shower curtain over him to keep burning embers from falling on him.

Eileen Bellew made it to St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx in time to say good-bye to John. When his body was taken out of the ER, 200 firefighters were packed in the hospital hallways, lining up in a double formation and saluting.

Racing in an FDNY van to the hospital, Jeanette Meyran tried to calm herself. There’s no chaplain with me? We’re good, then. We’re going to St. Barnabas, not the Burn Center? All right. She was ushered into the hospital past a gauntlet of TV-news crews. Firefighters escorted her through the crowds and into a waiting room. There was a man there she’d seen before, a man much shorter than Curt. It was Mayor Bloomberg.

“Mrs. Meyran,” the mayor said. “I’m so sorry.”

“Sorry for what?”

The mayor flinched. She hadn’t been told yet.

“He did it for the city,” he said.

“He did what for the city?”

The mayor tried again. “He didn’t make it.”

It took time for Curt to be cleaned up so that Jeanette could see him. In that time, she collapsed. Finally, she was brought through hospital hallways packed with firemen still wearing their gear, grime still on their faces.

Then she saw her husband. Curt looked exhausted.

“I knew him 25 years,” she remembers. “I knew his lip would dip a little when he was tired. But this just wasn’t real. And I just kept asking him to wake up.”

The two firefighters’ funerals were full-scale FDNY tributes—one in Pearl River, the other on Long Island, each drawing more than 8,000 people. Meyran’s 16-year-old son, Dennis, wore his father’s blue FDNY jacket. Bellew’s oldest boy, Jack, wore his father’s helmet.

Black sunday was instantly seen as one of the department’s darkest moments, and no sooner had the four surviving firefighters arrived at the hospital than people started looking for causes and attempting to place blame. First, there was the issue of safety ropes. The FDNY had long supplied firefighters with them, but had stopped doing so in 2000—ostensibly because they were too bulky and the men weren’t using them (some say cost was a factor). Now the question was whether the lack of ropes cost two men their lives and four others their careers. By April 2005, the four surviving firefighters and both widows filed notices to sue the city for not supplying ropes; the cases have since been consolidated, and the lawsuit is still pending.

Next there was the matter of the chopped-up apartment. From the day after the fire, the FDNY blamed the landlord for violating the fire codes and building a wall that kept the men from the fire escape. A year after the fire, the Bronx district attorney charged three people—the landlord and two tenants—for making alterations in the building; the case is still ongoing. If convicted, the three people charged could be the first in the city to be held criminally responsible for deaths because of alterations made to their apartments.

In September 2005, the FDNY filed a response of sorts to many of the questions about Black Sunday in the form of its official fatality report. The product of dozens of interviews and reviews of the transmissions and logs from that day, the report acknowledged that ropes might have been helpful that day but stopped short of recommending reissuing them departmentwide. The wall that blocked the fire escape was cited as a problem, as was the weather. But the report found fault elsewhere too—particularly with the men on the scene. For the first time, human error was suggested as a possible factor in the tragedy.

The six victims, according to the report, stayed on the fourth floor too long without a working hose line and failed to tell anyone on the ground that they were essentially trapped. Others were blamed, too—like the men on the ground who didn’t order the men back downstairs as soon as the hoses failed and the men working the booster water pump when the hydrant failed—who, the report says, might not have understood how certain new equipment worked. And Curt Meyran, the report found, didn’t identify himself properly with his first Mayday call.

The issue of whether the city is culpable for anything it did or didn’t do, it bears noting, was scrupulously avoided. But a month after the report was released, the FDNY brought back the ropes.

It’s a clear day just before New Year’s, and Gene Stolowski is standing in the driveway of his split-level house in the foothills of the Catskills, an hour’s drive from the George Washington Bridge, watching his 4-year-old, Briana, teeter on a bike with training wheels. Of the four survivors, Stolowski has endured the slowest and most painstaking recovery. He was given his last rites three nights after the fire when he developed a blood clot on his spine. Doctors took seven hours to place titanium screws in his skull and neck. He had eight more surgeries in the first two weeks and fought off infections and 106 degree fevers. Doctors gave him a 5 percent chance of survival. Then, weeks later, Stolowski moved his fingers. His physicians began to see hope for a recovery.

Briana was kept from seeing Stolowski for a month after the accident because he looked so scary. When Briana asked one day if her daddy loved her anymore, Stolowski’s wife, Brigid, decided to let her see him. “That’s not my daddy,” Briana said.

On February 22, 2005, Stolowski was released to a rehab center but given a 30 percent chance of walking again. He didn’t come home until the following September, eight months after the fire. On April 12, 2005, thrown into labor two months early by the stress, Brigid delivered twin girls, Kaitlin and Kailey. For the next year, Brigid was handling two newborns, a toddler, and a husband who couldn’t get to the bathroom on his own.

Stolowski’s firefighter pals built a shower on the ground level of his house and rigged it for a wheelchair. He walks now, with a limp, and he can hold the babies in his lap, even lift them. But he’ll always have a neck problem; he can’t turn his head more than a few inches in either direction. Sometime in the next few years, he’ll need another neck surgery. And money’s a problem: On permanent medical leave, he’s collecting just his regular salary now, no overtime.

The other survivors have lived through variations on the same grim themes. Doctors had to remove Jeff Cool’s vital organs from his chest to reduce swelling; he received 46 pints of blood and stayed in a coma for three weeks before being released from the hospital on February 18. He still walks with a limp, has constant pain and needs regular physical therapy, and, like Stolowski, was placed on permanent medical leave. Joe DiBernardo underwent eleven hours of surgery on his right leg and nine hours on his left; his coma lasted eighteen days, during which he twice received last rites. When he finally awoke, he was 40 pounds lighter—despite the addition of ten titanium plates and 60 screws in his lower body. On May 10, 2005, he was promoted to lieutenant, though it was clear he wasn’t going back on duty; that day, he took his first steps without a cane, and a few months later, he danced at his sister’s wedding. But he lives with chronic pain, and by Thanksgiving, he was back at Weill Cornell when some of the screws in his left leg had begun to shear off, ripping into his muscles. In January 2006, he signed his retirement papers.

Brendan Cawley’s mother pleaded with the doctors not to let him die. Cawley’s brother Michael, also a firefighter, was killed on 9/11—one son lost was more than enough. In fact, Cawley was the luckiest, relatively speaking, of the four survivors. Despite his multiple fractures and a brain hemorrhage, he was released from the hospital just six days after Black Sunday. At first, he thought he’d be back at the firehouse by September. “I didn’t have a shot,” he realizes now. For the next year, he was in physical therapy. He did light duty at the fire academy last summer, helping out instructors and hanging around with the probies. But then he needed another shoulder surgery in September and was placed back on medical leave. Kerry Kelly, the chief medical officer of the FDNY, has encouraged him not to give himself any deadlines. “She said to me, ‘Let’s get Brendan back to being Brendan again, and then being a firefighter.’”

The survivors and the widows share other common bonds—grief, guilt, doubt, anger. “I always tell the probies when they go out to the field that if you’re going to see this report, to take it in the bathroom stall and wipe your ass with it,” Gene Stolowski says of the fire department’s summary of the tragedy. It’s not that the report fails to deal with the ropes or illegal partition wall, he says. It’s that it weighs them equally with all the other factors; it assumes everything has the same importance. He particularly bristles at the notion that Meyran should have ordered the men out earlier. “Some guys can read this report and think that we were in an untenable position and should not have been in there. They don’t get the sense from this report that we were driven to the floor. You know, we weren’t hanging out in there for no reason. The shit hit the fan as fast as it could.”

Still, it’s not like Stolowski doesn’t replay the fire in his mind. “For whatever reason, I never went into the kitchen,” he says. He’s talking about how he might have found the hallway that led to the fire escape. “I don’t know why. Sometimes I kick myself in the ass. You always second-guess yourself.”

Then he turns wistful. “Yeah, I tell everybody I would go back tomorrow and do it again,” he says. “I will always say it’s the greatest job. To be able to do what we did—you know, just run into a burning building? It’s crazy!” He laughs. “I won most of the fires I was in. And I guess I only lost one. That was January 23rd. We lost.”

Unlike the others, Brendan Cawley is still hoping to get back to work, but even if he proves physically able, he still has emotional issues. “I don’t want to say I’m claustrophobic,” he says, “but when I think about what I had to do that day, I’m probably more scared now.” He has grown close to the widows and their families; being with them, oddly enough, helps assuage his survivor guilt. “I guess I can relate to their losses because I went through it, losing my brother,” he says. “But these poor kids, losing their dad, that’s hard. And it was so avoidable.” He says he owes a special debt to Meyran. “A lot of guys say he was the boss, he should have been the last one out,” Cawley says. “But I don’t know if I would have went if he didn’t go first.”

Joe DiBernardo was the only one of the four survivors who wouldn’t be interviewed for this story; going over Black Sunday again wasn’t good for his recovery, he said. But his feelings about the case against the landlord and tenants are clear. “They can lock them up, put them away forever on manslaughter charges,” he told a newspaper last year, “but that doesn’t change the fact that I’m not going to be a firefighter again, that I’m living with a broken body and there are two widows and all these fatherless children.” (All three defendants maintain their innocence. Ironically, one of their lawyers, Sam Braverman, has seized on the ropes issue as a defense. “The illegal subdivision did not cause their deaths,” he said last March. “If these firemen had ropes, my client would not be in jail right now.’’)

Even from his bed at St. Barnabas, Jeff Cool begged fire commissioner Nicholas Scopetta to bring back personal-safety ropes. Now he’s become an activist on the subject, lecturing at fire trade events and lobbying officials around the country. New York’s getting them is not enough, he says—though he says it’s clear why the men didn’t have them that day. “I’m telling you right now, it had everything to do with dollars.” As sure as he’s standing there, he says, the $375 rope he’d bought with his own credit card saved him and Joe DiBernardo. Now he wants national legislation for every firefighter to have one. Failing that, he’d like the National Fire Protection Association to change its standards to include personal ropes and harnesses for each firefighter. He’s also lectured probies on the subject, “but I think I scared the shit out of them, because I haven’t been asked back.”

Cool is just as outspoken on the question of the chopped-up apartment. “Here we are on the two-year anniversary of this fire, and there’s no end in sight on where we are with this trial,” he says. “We’ve got three criminals, safe as can be, walking around with their lives. They were enjoying Christmas, enjoying New Year’s. The four of us are screwed up beyond belief. Two of us are dead. And these guys are walking the street.”

On February 9, two weeks after the fire, with department personnel still chauffeuring her and the kids, Jeanette Meyran asked to visit the building where Curt died. She came away appalled. Even forgetting the fire, “the place was filthy,” she remembers thinking. Then she got mad. “I can’t believe he risked his life for people like that. Poor is one thing, filthy is another. This is what he was fighting for?”

Then, just as quickly, she softened. “I never knew this was what he faced every day. He risked his life—putting aside the adrenaline and the thrill-seeking. There was never an impossible situation for Curt. With him, there was always a way. He could fix it. He was so good at making us feel so secure. A few weeks later, I remember being at a mall with the kids, and my son turned and said, ‘Mommy—I feel so unprotected.’”

“It’s a dirty, dirty game,” said the widow. “Human error. Lines frozen. Hydrants. I know who to blame.”

Exiting the apartment, Jeanette made a statement to the press, who’d been tipped off to the widow’s visit. Inside, she’d seen a radiator and a TV console. Curt could have tied off to either one, had he been given a personal-safety rope. By the following October, when the city announced it was giving safety ropes to every firefighter again, Jeanette came to the event uninvited and said, “A day late and a dollar short, obviously.” Later, turning up at another FDNY event, she remarked, “I would not be here today but for a lousy piece of rope.”

As for the FDNY’s official report, she says, “It’s a dirty, dirty game. Human error. Lines frozen. Hydrants. If my husband had a rope, he might be here. If John Bellew had a rope, he might be here. I know who to blame. They died in that building. They worked for the City of New York.”

In January 2006, at a ceremony marking the first anniversary of the fire, Bloomberg and Jeanette met again.

“Jeanette,” she remembers him saying. “You have to stop this crusade. It’s been a year. You have to move on. Curt would not want his widow to live this way.”

“I appreciate your concern,” she remembers replying. “But how does that help me and my children?”

Bloomberg looked away from her. “Take care of this woman,” he said, and walked away.

“There’s a protocol for the FDNY widow,” Jeanette says now. “You’re in shock, then you go away. I’m not following that protocol.”

Eileen Bellew is also a party to the ropes lawsuit. But unlike Jeanette, she’s reluctant to play a part in any publicity about the tragedy. In a sense, culpability is a nonissue for her; she’s resisted making her husband’s life about any one issue. “I still have to get up every morning,” she said when the charges were filed, “and take care of four kids.”

Jeff Cool is retiring today. It is the Tuesday before Christmas, and Cool, wearing a black Rescue 3 golf shirt and dark-blue jeans, is at the FDNY headquarters in Brooklyn. “Why now?” someone he knows asks him in the lobby. The answer has to do with his medical benefits: He’ll still have three-quarter’s salary, but now that he’s sufficiently recovered, he’ll go to an HMO.

Cool takes the elevator to the office where the final paperwork will be done, wandering through a maze of gray cubicles and stopping at one in the back. There is a woman sitting there. He takes a breath.

“I’m retiring today,” he tells the woman.

“Regular or three-quarters?” she asks.

“Three-quarters,” he says. “Here’s the form.”

She looks at the form. “Oh, you’re Mr. Cool!”

“Yeah,” he says. “The chief told you about me?”

“Yeah. How you feeling?”

“Pretty good,” he says. “Well, I have pain every day. I’m lucky to be alive.”

“I hear that.”

It’s time to get a picture taken for his retired-firefighter I.D. “You’ll have to put a firefighter shirt on,” she says.

He glances at his Rescue 3 golf shirt—but she points to a gray filing cabinet behind him. Dangling from the lock on metal hangers are a few FDNY dress shirts with ties pre-done around their collars.

He has a choice: white or blue. He puts on a white shirt and black tie.

Jeff Cool has a recurring dream now where he’s back at probie school. An instructor he remembers is talking to his class of 109 guys, and he’s sitting there with the rest of them, listening. The instructor is talking about someone, he’s not sure who. But he’s saying, “He was a good firefighter. But he died. Look around at this class. Some of you guys aren’t going to make twenty years.”

And in the dream, Cool looks around and says to himself, “Well, we’ll see.”

That’s when he usually wakes up.

“Are you ready?” the woman says, fiddling with a digital camera.

“Yes.”

“Smiling is good.”

He smiles.

Flash.

Anatomy of a Fall

(1) Firefighters Curt Meyran, Gene Stolowski, Brendan Cawley, and John Bellew, all from FDNY Ladder 27, arrive at 236 East 178th Street in the Bronx at approximately 8:05 a.m. on Sunday, January 23, 2005. Firefighters Jeff Cool and Joe DiBernardo, from the FDNY’s Rescue 3 unit, arrive soon after that.

(2) With firefighters from other companies already battling the blaze on the third floor, the main site of the fire, Meyran, Stolowski, Cawley, Bellew, Cool, and DiBernardo are sent to the fourth floor to clear it and prevent the fire from spreading. The six men case the area, but their efforts are made difficult by dense smoke and the mazelike structure of the chopped-up tenement building. Because of problems with a hydrant and other equipment, the men are also operating without working hoses.

(3) A burst of fire erupts through the third floor, trapping the six firefighters in Apartment 4-L. Their attempts to find a safe way out are thwarted by an illegal partition wall (in red, above) that hampers their efforts to find a fire escape.

(4) With the flames inches from their backs, the six men are forced to jump from four windows—a 50-foot drop. Meyran and Bellew die from the fall. They are survived by their wives and seven children, ranging in age from 5 months to 16 years old. The four other men suffer multiple critical injuries, are left with permanent disabilities, and are forced to retire from duty. The four survivors and two widows later sue the city for not supplying the firefighters with personal-safety ropes. Pinning the blame on the partition walls, the Bronx district attorney charges the building’s landlord and two tenants with manslaughter, criminal negligence, and reckless endangerment. Both legal actions are ongoing.

Diagram: Anatomy of the Fall