If he weren’t famous, he’d be mistaken for a veteran of a long-ago war: khaki safari shirt on his back, scuffed combat boots on his feet, that wiry crest of a brow, rheumy eyes under heavy lids, lower lip jutting out like an ornery fish resisting a hook.

When Dan Rather sits on a bench in Central Park to tell how his 44-year career at CBS News ended in ignominy and humiliation, he is in fact still waging a war, a bitter and personal one. And the memories of the battles that undid him are still fresh on his mind. “Monday morning, about 8:49—and I think that is the time precisely,” he says. He’s recalling January 10, 2005, when he first received the 224-page report commissioned by CBS that excoriated his infamous 60 Minutes Wednesday segment on President Bush’s National Guard service. Of that report, Rather says, “When I read through it, all I could say to myself, on each page, is, ‘What bullshit. What pure, unadulterated bullshit this whole thing is. What a setup. What a fix.’ ” He nearly spits the word fix.

Three years later, Rather cannot forget. He’s suing CBS and its former parent company Viacom—along with Viacom’s chairman, Sumner Redstone; CBS chief Leslie Moonves; and former CBS News president Andrew Heyward—for $70 million. The core of Rather’s lawsuit is a mundane contract dispute over whether he received the airtime he was promised in his final year on CBS. But like Rather himself, it’s charged with hurricane-force drama, draped in a larger tale of conspiracy and corruption. He hopes that depositions and subpoenas can complete the unfinished business of “Rathergate,” proving not only that he was right all along, that his National Guard story was accurate, but also that CBS buried him so Sumner Redstone could shield Viacom’s corporate interests in Washington from White House blowback. “My opinion,” says Rather, “is that Redstone is the heavy in this.”

This is Dan Rather’s last big story, his crusade to save his reputation as one of the late-twentieth century’s great TV newsmen. “Look, I don’t want to be some Don Quixote out here tilting at windmills, without even a Sancho,” says Rather. “I think when people hear what I was told and what I was not told by CBS executives concerning the Guard story, that they’ll understand.”

But with much unproved, Rather’s claims have left him standing alone. CBS has already fired back, motioning to dismiss his case and calling his allegations “bizarre” and “far-fetched,” his motives purely ego-driven. In launching his attack, Rather risks what’s left of his credibility: If the case makes it to trial, it could uncap the biggest media scandal ever told—or reveal Rather to be the crumpled icon of a fading era, courting madness in the twilight of public life.

It was only three years ago that Rather reported the story that would cost him his career, but the world was a very different place back then. It’s easy to forget now, when prosecuting Bush in the press has become commonplace, that in the lead-up to the 2004 election, much of the mainstream media was in a defensive crouch. “This administration was hammering people for much less controversial stuff,” says a veteran TV news producer. “When they were at the height of their power, post-9/11, they would call about anything, yell about anything, pressure people about anything.” And it seemed to be working. Rather claims CBS dragged its feet on his scoop on Abu Ghraib prison abuse, which ran only after the network learned it was about to be beaten by The New Yorker. (CBS says it held the story because it wasn’t ready.)

With conservative groups attacking Senator John Kerry’s record as a Vietnam War veteran, Bush’s own service was vulnerable, and Rather and his producer Mary Mapes went after it. In the summer of 2004, Mapes obtained four memos purportedly written by Bush’s former commanding officer in the National Guard, the late Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Killian, expressing discomfort at having to “sugarcoat” Bush’s record. There had been questions about whether Bush had completed his required Guard duty as early as 2000, but no one had come up with definitive proof that he hadn’t. The Killian documents appeared to be the smoking gun. With USA Today on its heels, CBS felt it had to rush the story on the air—some say the heaviest pressure came directly from Rather. Rather says he repeatedly asked Mapes if the memos were authentic, telling everyone the story was “thermonuclear.” When Mapes said they were real, that was good enough for him. The afternoon before the broadcast, CBS News showed the documents to White House spokesman Dan Bartlett, who didn’t deny their veracity but instead argued that they actually supported elements of Bush’s own version of events.

CBS declined to comment for this story, beyond releasing a statement saying the company is “mystified and saddened by the baseless and self-serving allegations and distortions of fact raised in [Rather’s] lawsuit.” So that leaves us with Rather’s version of what happened next. “The fact is, they caved,” he says. “They crumbled.” When the documents were savaged by right-wing bloggers and press critics, CBS News found it couldn’t prove their authenticity and backed down. And so, at the time, did Rather. After twelve days of scrambling to defend his story, Rather went on the air and said, “If I knew then what I know now, I would not have gone ahead with the story as it was aired, and I certainly would not have used the documents in question.”

Rather now claims the apology was “coerced” by CBS News president Andrew Heyward. Rather was still clinging to the story with both hands when Heyward asked Rather’s agent of 42 years, Richard Leibner, to mentally prepare Rather to let go. Later, the stunned anchor stood next to Heyward while his boss typed the script on a computer.

“I don’t believe what I’m hearing,” said Rather, slamming his fist on the dashboard. “You can’t do this,” he told Heyward. According to Rather, Heyward coldly replied, “It’s done.”

Rather went along with the company line—partly because he was shell-shocked, partly out of loyalty to the network where he had spent his entire career, and partly as an act of self-preservation. Rather believed that Heyward and Moonves would help him recover from the debacle and support his continuing efforts to prove the documents were real. “I love CBS News,” Rather says. “It was painful to me that we were going through this. And they’re saying, ‘Listen, we’re all in this together. You may not agree with everything we do, but [we’re] committed to your coming out of this as well as you can.’ ”

Two days after the apology, Rather’s faith in his employers was shaken. CBS announced it was commissioning an independent investigation into the flaws of his 60 Minutes Wednesday segment, to be co-chaired by former U.S. attorney general Dick Thornburgh, a Bush family friend and onetime Nixon confidant. Rather felt CBS was handing him over to his enemies for execution. When Heyward informed him that Thornburgh would lead the investigation, Rather was riding in a car in Manhattan with a CBS security guard assigned to him after he’d been mobbed by paparazzi. “I don’t believe what I’m hearing,” Rather told him, slamming his fist on the dashboard. “This is un-fucking-believable! You couldn’t have picked anybody who is worse.”

Rather says he told Heyward, “‘You can’t do this.’ And he very coldly said, ‘It’s done.’”

Already a chronic insomniac, Rather barely slept now, arriving at his office at 7 a.m. to make frantic calls to anyone and everyone, desperate to glue the story back together. After the 6:30 broadcast of the Evening News, he would stay on the set for hours going over the details. “He was crazed,” says a friend. “He looked exhausted.”

Rather and Mapes were told to cease their efforts to prove the Guard story, at which point Rather tried to hire his own private eye to continue digging. Heyward told him to stand down, that CBS would hire one instead. Rather says he was promised a copy of the P.I.’s report, although he never received one. (CBS claims its investigator, Erik Rigler, whom Rather now calls the “mystery man,” never found anything.)

At first, Rather refused to deal with the commission. “No good can come from this,” he remembers thinking. “It stenches of fix.” But again Heyward—along with Rather’s family and his agent—persuaded him to cooperate for the good of CBS. Rather and Heyward had known each other since the early eighties, when Rather plucked Heyward from the local New York affiliate to work at the network. Heyward promised they would get through the ordeal together. “He’d gone corporate long before this,” says Rather. “Nevertheless, I believed him.”

When he describes his eight-hour interrogation before the commission, Rather seems to relive the moment. He can visualize the seating chart of his inquisitors, pointing to exactly where Thornburgh sat. Former Associated Press chief Louis Boccardi was the only journalist on the panel, outnumbered by lawyers, Rather says, with two from Thornburgh’s legal team doing the bulk of the questioning. Thornburgh sat silent and coiled, waiting to interject “like a cobra strikes.”

“He’d get up right in your face: ‘Mr. Rather, you mean to tell me that after all of this you’d do a story with Mary Mapes?’ ‘Yessir, that’s exactly what I said.’ And then he’d shake his head,” says Rather. “I thought he was a total ass. He tried cheap Perry Mason tactics.”

As the commission’s investigation dragged on through the fall, Rather began to piece together his conspiracy theory. “As soon as we began to see that the company was wobbling,” says Rather, “I said to myself, ‘I think Redstone said to Moonves, Make this disappear. This is killing us in Washington.’” Now, everywhere he looked, he saw signs of his company’s caving to pressure from the Bush administration. Moonves told investors at a Goldman Sachs conference that the Thornburgh-Boccardi report would be delayed until “after the election, so it won’t affect what is going on.” In a Time magazine interview before the election, Redstone said his reaction to Rather’s report was one of “severe distress” and announced his preference of Bush for president: “I do believe that a Republican administration is better for media companies than a Democratic one.” It was an unusual political declaration from a media CEO. At the time, the Republican-controlled FCC had levied heavy fines against Viacom for shock jock Howard Stern’s on-air infractions, just as Viacom was lobbying the FCC for more media deregulation. Rather now suspects that Viacom’s top lobbyist in Washington, Carol Melton, suggested Dick Thornburgh for the panel to appease Republicans. (Soon after, Melton hired an outside lobbying firm to strengthen Viacom’s relationship with the GOP.)

Rather believes Redstone wanted him out because he was costing the company too much political capital. As evidence, he refers me to a paragraph buried deep in Edward Klein’s recent book about Katie Couric. Klein reports that Redstone declared in a board meeting, “I want anyone associated with that guy to go,” referring to Rather, because he was jeopardizing the company’s lobbying efforts on a major corporate-tax bill passing through the Republican-controlled Congress. Klein, a controversial journalist whose reporting on Hillary Clinton was pretty much discredited in 2006, insists the anecdote came from somebody “inside the room.” But another person who was present says Redstone never said that, although there were extensive conversations about Rather at Viacom’s board meetings. Subsequently, Viacom did lose its bid for tax breaks that could have saved it hundreds of millions of dollars.

On Election Night, Rather anchored the network’s coverage, staying on-air until 6:30 a.m. Four hours later, Rather says, he got a call from his agent telling him Moonves wanted him out of the anchor chair right away. He and Moonves had been discussing his retirement, and Rather knew his boss was angling for him to leave in the spring or fall of 2005. But the timing of the decision was suspicious. “This has to do with their relationship with Washington,” he recalls thinking. “If the election had gone another way, it might not have happened at that time.”

Rather’s shock turned to quiet fury. He stalked the offices, barely acknowledging staffers in the hallways. People referred to this mode as “Defcon 4.” “He got progressively, visually angry,” says a former colleague. “You don’t want to be in his eyesight when he’s like that.” His only release was commiserating on the phone late at night with Mary Mapes; he would announce himself as “Dan Rather, plus three”—meaning he’d had three glasses of bourbon.

A few weeks after the election, Rather and his agent met with Moonves to ask that Rather be allowed to stay on at the anchor desk until his 24th anniversary, three months away. Moonves reluctantly agreed, says Rather, and assured him CBS would stick by him. Afterward, Rather asked his agent to leave the room so he could have a private conversation with Moonves. Rather tried to appeal to his sense of justice. “I’m not sure there’s yet an understanding of what’s happening here,” he recalls telling Moonves. “We’ve done a true story, and they’re not denying it because they can’t deny it. And it’s very typical in American politics, whether Republicans or Democrats, what they look for is any place where they think you might be vulnerable and they try to make the conversation about that rather than the truth of the story. So I want to make sure, Mr. Moonves, that you understand.”

Rather describes the meeting as intense. “He listened very carefully,” he recalls. “‘I understand what you’re saying. We’ll get through this, and we’ll get through this together.’”

When his retirement from the anchor chair was announced, Rather went to the press with honeyed words for Moonves. “He actually watches news,” he told me in an interview at the time. “And he’s so sensitive to the CBS News traditions and history.”

When I read that quote back to Rather now, he darkens. “This is the way my mind works, small as it is,” he says. “I settle on something and say, ‘That’s where I stand.’”

Now, of course, he’s settled on something different. “Where I fault myself—and I fault myself on a lot of things—is that for the longest time I just refused to believe what my eyes saw and my ears were hearing.”

The atmosphere at 60 Minutes was poisonous for Rather. Deeply depressed, he was often heard to say, “I used to be Dan Rather.”

When the Thornburgh-Boccardi report landed in January 2005, Rather was spared: The panel concluded that he was not responsible for the failures of the Bush Guard segment (he was off covering a hurricane just before it aired) and that he wasn’t politically motivated; it even acknowledged that Rather “did not fully agree with this decision” to apologize on the air “and still believes that the content of the documents is accurate.” It wasn’t Rather’s proudest moment. All he had done was manage to avoid being the fall guy.

That honor would go to Mary Mapes, of course. Despite the fact that the panel could not determine whether the documents were authentic, Mapes was fired and three others—CBS News senior vice-president Betsy West, 60 Minutes Wednesday executive producer Josh Howard, and Mary Murphy, Howard’s senior producer—were dismissed. Rather blamed Heyward for not saving their colleagues. “I thought we were going to stick together through all this,” he told Heyward. According to Rather, Heyward said, “Dan, we’re so far beyond that it’s not even worth discussing.”

The plan seemed obvious to everyone except Rather: Mapes would be blamed, Rather would spend his remaining days doddering around the hallways at CBS (though certainly not producing news stories), and CBS would finally put this mess behind it.

At the time, Rather seemed determined to move on. He refused to cut off his relationship with Mapes, as CBS had requested (“I thought then and I think now that Mary shouldn’t have been fired,” he says), but he agreed to stop discussing the Guard story in public. He didn’t even seem interested in the news, which broke that spring, that a research assistant for Mapes had secretly recorded phone calls with CBS’ private eye, who on tape said he believed the Bush Guard story was “likely true” and speculated that CBS only hired him to prevent Mapes from suing. The day before his last Evening News broadcast, I shared that information with Rather, but the outgoing anchor was reluctant to fan the flames. Now those tapes are part of Rather’s lawsuit, but at the time he said it looked to him like “dots with no lines”—evidence that didn’t prove anything.

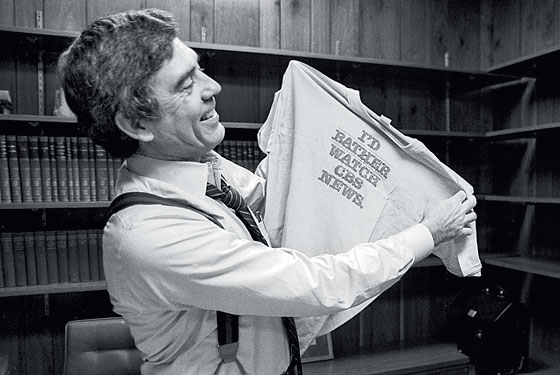

But the anger was seething just below the surface. The next night, Rather’s last as anchor of the CBS Evening News, he wore a T-shirt under his suit and tie that read F.E.A.—“Fuck ’em all.”

Rather still had a contract with CBS through November 2006, and as soon as he left the anchor chair, he began looking for stories to do at 60 Minutes. The trouble was that 60 Minutes didn’t want him. At a staff meeting around the time Rather was making the switch, the other correspondents told executive producer Jeff Fager that they didn’t think he was good for the program, that he had damaged the franchise. Mike Wallace, Morley Safer, and 60 Minutes founder Don Hewitt all slagged Rather in the press. “These guys came up behind me to deliver one big blow to the head while I was down,” he says.

The atmosphere at 60 Minutes was poisonous for Rather. Friends say he was deeply depressed. He was often heard to say, “I used to be Dan Rather.”

His main complaint was that he wasn’t getting any airtime. He recalls the big blackboard that listed the correspondents and their assignments: “Over in one little corner, it was in chalk—just about six inches in length and maybe four and a half inches in width—was ‘DR.’ And there was nothing under it.” And when the time came to shoot the group portrait of the primary 60 Minutes correspondents for the fall, Rather says he was left out. “Someone on the outside would say, ‘This is piddling stuff,’ but when you work there, it’s not piddling at all.”

Rather managed to get only three segments on 60 Minutes in 2005, and two of them ran on Christmas and New Year’s—clear attempts, Rather claims, to make him invisible. Lawyers for CBS argue that they were not contractually obligated to put Rather on the air, only to pay him.

But Fager says Rather was actually given an enormous budget and three producers and offered ten segments for the next season. He says Rather simply didn’t produce high-quality material, though he did produce one of the most expensive segments, flying his crew to North Korea. “It’s a meritocracy,” says Fager. “We don’t air stories because you did them,” referring to Rather.

Rather felt betrayed by Fager, who was a longtime friend and a former executive producer on the Evening News. Fager wore a Rolex Rather gave him featuring the anchorman’s signature hurricane logo on the back of the dial. “I took Jeff out of obscurity,” Rather says. (Fager denies that Rather was responsible for his rise in the company: “I did as much for him as he did for me.”)

The next summer, Rather was told his career at CBS News was effectively over. He was offered an office and a secretary but no airtime. Though he was still owed one documentary on his contract, CBS turned it into a one-hour program called Dan Rather: A Reporter Remembers.

Two years into Bush’s second term, the discredited National Guard documents were little more than a footnote in the story of the 2004 election—never proved real, never proved fake. But getting squeezed out at CBS had made Rather realize that they were going to follow him to his obituary. The only way out of the predicament, the only way to redeem his reputation, was to finish the story he and Mapes had started. And so, within a month of leaving CBS, Rather set out on a quest to find out what really happened, hiring three investigators to help him prove, once and for all, that the documents were authentic.

Like Kennedy trying to solve his own assassination, Rather explored every possible conspiracy theory, from Karl Rove’s planting passable fakes to damage him to a National Guard employee’s typing up copies before the originals were destroyed. “I’ve been down every one of those rabbit holes and 50 more,” says Rather, “including people saying, ‘You come up with $200,000 in small bills…’ About that I say, ‘Listen, I’m not going to pay for anything.’”

The case against the documents had boiled down to two critical weaknesses: The first was their modern font spacing, which several experts claimed could not have been produced on an early-seventies typewriter. Then there was the source, Bill Burkett, a disgruntled former National Guard employee who, say the detractors, hated Bush and misled CBS about their provenance. Rather had always believed that the arguments regarding typeface were merely a right-wing distraction, and that pitting experts against experts was a no-win proposition. What he needed to do was to follow Burkett’s paper trail—if he could prove where the documents came from, he could prove their authenticity.

The reporting was difficult. Sources changed their stories from day to day. Tips led from far West Texas to the Louisiana border, from retired secretaries to a drunk in a trailer park. Several witnesses, including current and former Guard employees, refused to talk on the record, saying they didn’t want to be put through the ringer as Burkett had been. “We very quickly got into the miasma of the thing,” says Rather. “I wish we could have dealt all the time with priests and rabbis and angels, but that’s not the way it works.”

Here is what Rather, after his investigation, believes happened with Bush’s National Guard records: In 1998, as Newsweek first reported, Harriet Miers (then Bush’s lawyer, later his Supreme Court nominee) and her firm were paid $19,000 to examine Bush’s Guard record for “vulnerabilities” in the run-up to his bid for the presidency. Rather believes Burkett’s allegation that the documents were “scrubbed” rather than examined. “There have been documents that have been shredded,” Rather asserts. “That’s a fact.” (Former White House spokesman Dan Bartlett admits that he was involved in examining the records, but calls the scrubbing allegation “an outrageous claim … the type of conspiracy theory that gives politics a bad name.”)

According to this version of events, unknown National Guard employees purloined some of the damning documents before they could be destroyed. Then, somehow, they came into the hands of former Guardsman Burkett. Burkett’s story about how he got the documents is bizarre: He claims they were given to him by a mysterious (and some say fictitious) woman named Lucy Ramirez, who arranged to have them hand-delivered to him at a Houston cattle show. Rather believes this handoff did in fact happen but that it had been concocted to conceal the fact that Burkett and his buddies had stolen the documents themselves.

“This is how it appears to have happened, or a way it could have happened,” says Rather. “That’s a working and, I think, reasonable hypothesis.”

Still, Rather is ultimately relying on the same source who got him into trouble in the first place. Why does he believe his documents are real now? There are two reasons: “First of all,” he says, “the story is true. Here is the proof that the story is true: Nobody has ever denied what was reported in the story. President Bush has not denied it, nobody at the White House has denied it, and nobody connected with the Bush administration has denied it.” (Actually, Bartlett does deny what CBS reported: “We believe the story is inaccurate, both the general thrust of it and the questionable sources they used,” he says. “I’m not a forensic specialist, but many people who are concluded the documents were fraudulent.”)

The second reason Rather believes the documents came from Bush’s file is a piece of information that he is privy to, but the rest of us are not—at least not yet. Rather says his lawyer has interviewed a credible eyewitness to the alleged shredding (and stealing) of the Bush documents who has agreed to tell the story under oath. But the witness refuses to come forward until Rather’s case goes to trial.

That leaves Rather twisting in the wind for now, a bit desperate for more information that will help him connect the dots. “If anybody knows anything,” he says, “now’s the time for them to come forward. If Burkett’s got something, now’s the time.” He repeats the phrase, looking for the right emphasis. “Now is the time. Now is the time.”

Rather won’t discuss when precisely he began thinking about filing suit. But one likely catalyst was Mary Mapes. In the fall of 2006, Mapes published a book, Truth and Duty, that defended the Bush Guard story and suggested a Viacom–White House conspiracy. What was in the book wasn’t surprising to Rather. What was surprising was that after its publication, Mapes hired a high-powered Houston lawyer named Mark Lanier to draw up a lawsuit against CBS, and CBS responded with a settlement before she had even filed it. What was in the suit that Mapes hadn’t included in her book? What would make CBS so eager to settle? The settlement required that Mapes sign a confidentiality agreement, and she couldn’t talk about it, even to Rather. (Mapes and CBS refused to comment on her suit.) Her settlement made Rather feel like he was the last of the Guard-story veterans left standing. The three other CBS staffers dismissed in 2005 had already settled as well—Josh Howard for $3 million. “Every other person has taken the money for silence,” says Rather. He thought of himself as the only one who could still uncover the truth.

Rather consulted several lawyers about the prospect of suing; they warned him that it was not only risky to face off against a $26 billion corporation like Viacom; it probably wasn’t worth the public scrutiny. “The likelihood is this will be long and it will be really tough—tougher than you imagine,” he recalls of the advice. “They’ll throw everything in the world at you, and don’t forget they have very deep pockets. They probably know your weakness, which is your family. And they have ways of putting pressure on pretty heavily with that.”

By the spring of this year, preparations for the suit were under way, with Martin Gold, the attorney who negotiated Rather’s acrimonious exit from CBS, interviewing potential witnesses in Texas. Still, Rather hadn’t quite decided to pull the trigger. He would spend summer evenings strolling alone along the tree-lined paths in Central Park, mulling it over in his head. He consulted a tight circle of people, and everyone had a different take on the situation. His wife of 50 years, Jean, told a friend she wished Dan wouldn’t fight this battle; she wanted to begin their life of retirement in Texas. Their two grown children, daughter Robin in Texas and son Danjack, an attorney in Robert Morgenthau’s office, urged him on. His agent didn’t support the lawsuit, not least because it would complicate his business with CBS.

Rather was anguished. “For two years he’s agonized about his reputation and finally said the hell with it,” says his close friend David Buksbaum, a former CBS News producer who accompanied Rather on several of his Central Park walks. “He couldn’t believe the company he bled for for 40 years would do it to him. It’s not about money, it’s not even about ego. It’s about vindication.”

Ultimately, says Rather, “I could not find a sufficient answer to the question of, Why not make a stand? If not now, when? If not you, who?”

Rather’s lawsuit has made him radioactive, even among his allies—many of whom would not speak about him on the record. It has also opened him up to criticism that he held on too long—both to his job and to the story—and, as CBS has stated in its legal rebuttal, that suing is his desperate attempt to return to public significance. Several of his former associates from CBS believe Rather should have bowed out gracefully like NBC’s Tom Brokaw. “He should have gotten out of this place a long time ago,” says a 60 Minutes producer. “He seemed to have no ability to make that choice and cross the line. He just moved the line.”

Rather insists he’s not just clinging to his public profile. “I can say truthfully I’ve never thought of it that way,” he says. “Being on television every day can be egocentric and it can develop an almost egomaniacal quality to it. That’s undeniable. And frankly, if you only do the anchoring work, you’re much more susceptible to that.”

People invariably laugh when you ask them to analyze Rather. Even Rather gives a smile and admits that figuring him out “may be full-time work.” Still, everyone has an opinion. Some of his friends think he’s brave to take on CBS; others see it as a little tragic. “It’s kind of sad that he feels like he has to do this,” says one admirer. “It’s going to zap a lot of his energy.” Morley Safer thinks Rather is suing because he “enjoys being a martyr.” For his detractors, there is also the whiff of insanity that clings to such a quixotic cause. In conversation, Rather doesn’t seem particularly crazy. But the “Crazy Dan” theme—“Gunga Dan,” “Courage,” “What’s the frequency, Kenneth?”—still trails him.

“I’ve been a reporter for 58 years,” says Rather, not terribly happy that I’ve brought it up. “That old saying, as you go through life your friends fall away and your enemies accumulate—when you insist on being independent, sometimes with a capital I, people who are highly partisan politically, on all sides of things, when you don’t report things the way they want you to report it, they call you eccentric or wacky or biased or what have you.

“I’m not proud of this, but I fight back,” says Rather. “That’s just in my id.”

In the weeks I spent talking to him, Rather was still hustling like he’d be on the news each night at 6:30 in front of 7 million viewers. His schedule is packed with reporting trips for his current employer, financier Mark Cuban’s tiny cable channel HDNet, taking him to the Arctic Circle one week, California the next. Despite how few viewers can see his program, Dan Rather Reports—only 7 million people subscribe to the entire network—he still carries himself with the hallowed dignity of a Founding Father. His sonorous voice and Yoda-like phrasing (“Widely believed this may not be, but true it is,” he says at one point) now have a spectral force, like the ghost of televised evenings past. At 76, he’s modern enough to use a BlackBerry, but he types the word eye for the first-person pronoun. It’s a strange gesture that makes it difficult not to think of the CBS eye logo, forever embedded in Rather’s identity.

A judge will make a determination about whether to send Rather’s case against his former employer to trial early next year. CBS argues that Rather’s suit was filed after the statute of limitations and is baseless in any case. But Martin Garbus, the lawyer who represented Don Imus in his $30 million suit against CBS (which Rather says was not an inspiration for his suit), believes Rather has a strong-enough case that it will likely get tried. “It’s a good argument,” he says. “This is a bad time to be a corporate defendant and it’s a bad time to be CBS.”

Should Rather win, he says he’ll donate much of the money to the cause of investigative reporting and protecting newsrooms against corporate interference. He’s already written fourteen chapters of a book about the principles at stake, which he hopes to publish in the spring. On the park bench, Rather pulls a notebook from his pocket. “I still carry a reporter’s notebook,” he says. “Old habits die hard.”

He flips through the pages, each filled with longhand script in blue ink. At the top of one page is scrawled: “Why did you do it?” He begins to read. “The court action has at its core the protection of the rights of journalists, not to make them a journalistic private class, but to safeguard the liberties of us all by preserving one of the indispensable elements of responsible government, which is the right to report freely on the conduct of those in authority.”

He pauses and flips the page to a note to self, to “DR”: “I staked on this professionally my all. To some it may be folly, but I believe in it and I believe in its importance.”

He looks up from his pad. He’s inspired now. “Since I believe in it, why can’t I suck it up and speak up for it?” he asks, almost talking to himself. “Look, it may all go to hell in a hack. There are plenty of opportunities for that to happen. I was concerned about having … decider’s remorse. It’s not as if you can make this decision and go back on it.”

But in some ways, the decision was a foregone conclusion. “I’m a story breaker, I’m a storyteller,” he says. He finds several ways to phrase it, each more emphatic than the last. “I was a reporter, not just one who played one on television.”

As the sun lowers in the trees, Rather seems lighter, unburdened. “If I’m about anything at all—and I try to think I am—then it’s getting to the bottom of a story,” says Rather, “and this is, however anybody thinks about it”—he leans forward now, reporter to reporter, conspiratorial, a hint of danger in his eyes—“this is a good story.”

SEE ALSO:

The Documents That Started It All