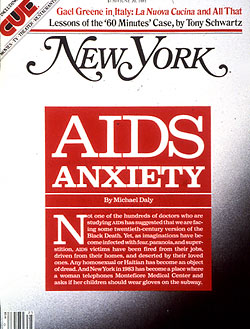

From the June 20, 1983 issue of New York Magazine.

On a Sunday morning last winter, model Susi Gilder flipped through a New York Times fashion supplement and came upon an advertisement that featured a friend who no longer looked like himself. The friend’s name was Joe Macdonald, and once he had been one of the hottest male models in the business. Now the face was drawn. The athletic build had melted away, leaving his body thin and wasted. And as she studied Joe Macdonald’s final appearance as a model, Susi Gilder caught a glimpse of the horror of an illness called AIDS.

“He looked very old,” Susi Gilder remembers. “The eyes were just very sad.”

Over the days that followed, everybody Susi Gilder encountered in the modeling world seemed to be talking about the photograph of Joe Macdonald. The gay men spoke of how terrified they were of suffering a similar fate. She remembers, “A lot said, ‘I think I’m going straight. I think I’ll try it again.’ Then they said, ‘You want to try it, Susi?’ “

This spring, Joe Macdonald died. Susi Gilder’s own misgivings about homosexuality had always been limited to a pang of regret upon meeting an attractive man who was not interested in women. She now began hearing women models who had shared this view say they planned to avoid using brushes belonging to makeup artists who were gay. After all, conjunctivitis was sometimes spread that way. Some makeup artists tried to reassure the models by saying that they soaked their brushes in alcohol.

When one model was greeted by a gay gentleman with a kiss on the lips, she ducked into the bathroom and washed out her mouth.

“Some of the models are paranoid,” Susi Gilder says. “They say, ‘Don’t kiss ‘em.’ They’re joking, but not really.”

Soon, even male models who had always been considered heterosexual became targets of this fear. One was a young man who had been recruited on the West Coast. He had a long mane of brown hair and a Tarzan-like build, and when he arrived in New York he aroused the passions of women models more than any male model in Susi Gilder’s memory.

“Everybody was saying, ‘He’s so cute,’ ” Susi Gilder remembers. “Everybody wanted him.”

Then Susi Gilder began hearing some of the women suggest that the young model had been in New York too long for them to be certain that he was still the strict heterosexual he had been in California. Although there was no evidence that this was indeed the case, the speculation caused a number of women to become fearful that the model’s beautiful body might harbor the dread contagion.

“They say, ‘How do you know? You don’t know,’ ” Susi Gilder says.

At the end of last month, Susi Gilder’s hairdresser showed her a newspaper article reporting that some doctors in the Bronx had come upon a case of AIDS that had been heterosexually transmitted. “He said, ‘See, it’s like herpes,’ ” she recalls. Susi Gilder says that while she still harbors no fear of being around gay men, she plans to have a discussion concerning monogamy with her boyfriend, Eddie.

“I’m going to beat Eddie and tie him up and say, ‘Don’t you dare,’ ” Susi Gilder says.

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome. At the Zoli modeling agency, on East 56th Street, and in the cubicles of the Everard Spa, on West 28th Street. Backstage at the Metropolitan Opera and in the locker room of the 6th Precinct station house. At an advertising agency off Eleventh Avenue and in the cellblocks at Auburn prison. Everywhere, talk of AIDS is erupting into conversations. One moment there is idle chatter about the Yankees or the new Lucas film. And then, suddenly, fear and reason are grappling with the specter of this fatal illness for which there is yet no cure.

Fear says that the number of cases is doubling every six months. As of May, there were 722 cases in this city. In two years, that number might reach into the thousands.

Reason says that AIDS has not broken out of the primary risk groups to a significant degree. A recent count showed that 72 percent of the victims were male homosexuals. Another 17 percent were intravenous-drug users. Just 4 percent were Haitians. And 1 percent were hemophiliacs.

Fear says that a 26-year-old sanitation worker in the Bronx came down with AIDS without any clear link to a risk group. Three women have also fallen ill for no known reason. Other victims include 25 city youngsters who apparently had infected mothers, eleven women who had sexual relations with members of a risk group, and ten people who received transfusions of blood that may have been tainted.

Reason says that AIDS appears to be the work of an infectious agent that can be transmitted sexually, perhaps by blood, or by contact between parent and child. There is no evidence that AIDS can be spread by casual encounters or through the air. And in the two years since the disease was first officially reported, not a single health-care worker has caught the illness from a patient.

Fear says that AIDS may lurk inside a victim for from six months to two years before the onset of symptoms. And during this time the victim can infect others. An airline pilot who shuttled between New York and Los Angeles apparently passed the illness on to four lovers in each city. In a three-month period, all eight lovers died.

And reason says that those who are not in fact seriously threatened should not let panic add to the sufferings of those who are already affected by the disease itself. Not one of the hundreds of doctors who are studying AIDS has suggested that we are facing some twentieth-century version of the Black Death. Yet, as imaginations have become infected with fear, paranoia, and superstition, AIDS victims have been fired from their jobs, driven from their homes, and deserted by their loved ones. Any homosexual or Haitian has become an object of dread. And New York in 1983 has become a place where a woman telephones Montefiore Medical Center and asks if her children should wear gloves on the subway.

One moment there is idle chatter about the Yankees or the new Lucas film. And then, suddenly, fear and reason are grappling with the specter of this fatal illness for which there is no cure.

One of those who witnessed the first stirrings of this fear was a 28-year-old AIDS victim named Michael Callen. He comes from a section of Ohio where homosexuality is considered at best a crime against nature. He was raised a Methodist, and he sang in the church choir. He remembers that he often prayed for relief from his sexual urges.

“I was tortured over my gayness,” Callen says. “I used to pray, ‘Please, if you’ll just take it away, I’ll be wonderful.’ “

There was no divine intervention, and Callen began reading all he could about sex. One writer suggested that homosexuals tend to congregate in bowling alleys. “I started driving around to every bowling alley I could find, all to no avail,” Callen says. When he was seventeen, he traveled east to pursue a singing career. After an audition, he needed to use a rest room. The nearest facility was full, so Callen went to the one on the floor above. He saw a group of men lounging by the stalls for a purpose he intuitively understood.

“I thought, ‘I am home, there are others like me,’” Callen said.

Over the next year, Callen pursued his sex life in toilet stalls, referred to as “tearooms.” He remembers, “It was smelly and sordid and dirty, and I thought, ‘This is my life.’ ” One day, a man slipped Callen a note written on a sheet of toilet paper. The note asked if they had met at the baths. Callen took another sheet of toilet paper and scribbled a message asking, “What are the baths?” The man wrote back, “Are you serious? Meet me outside.”

Soon, Callen was going to the baths every other day. There were no windows. There were no clocks. There was no music. There was only continuous, impersonal sex, often with men whose early lives had been as tortured as his own. “I was lonely and horny,” he says. “I was going to prove my parents wrong.” He had sex with hundreds of men before he had his first romantic affair, a passionate relationship with a police officer that shattered after a year. On a Christmas Eve, Callen ended up back at the baths, singing carols.

During his encounters at the baths, one infection after another invaded Callen’s body. He then passed the infections on to other men, who in turn passed them to still others. The medical charts of the men in the baths began to read like something out of Biafra. In 1979, Dr. B.H. Kean, of the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, called the baths a public-health threat. Kean wrote, “The patient would be treated for a second, third, fourth, and fifth time…. The patient has been infected again and again on a monthly basis.” The baths stayed open. And whenever Callen fell ill, there was always a pill or a shot that would allow him to return to the cubicles.

Then out of the swarm of microbes there appeared something that eluded all of the medications and was able to subvert the trillion-plus cells of the immune system. This was most probably a virus, bits of DNA coated with protein. While Callen coupled in the baths, the bits of DNA slipped into his blood cells and took over the reproductive machinery. More bits of DNA were produced, and more cells were invaded. After a time, Callen’s immune system became a junkyard. He began suffering fatigue and swollen glands. Finally, in December of 1981, he went to Dr. Joseph Sonnabend for a blood test.

“He said, ‘You are immune-deficient,’ ” Callen remembers. “I said, ‘What does that mean?’ He said, ‘Nobody really knows.’ ”

And so, a decade after fleeing a part of Ohio where homosexuality is seen as spiritual sickness, Michael Callen found himself alone in an apartment in New York with a physical sickness that threatened to kill him. He remembers, “I called my parents and said, ‘I’m going to get cancer.’ It was like a death sentence. I was just waiting to die.” The federal Center for Disease Control reported at one point that some homosexual AIDS patients had listed more than 1,000 sex partners. Callen sat down and began to compute his own total.

“I was thinking maybe a thousand, and then I was thinking, no it can’t be,” Callen remembers. “Lo and behold, it was more.”

As news of this illness spread, Callen noticed that many of his friends no longer greeted him with a kiss on the cheek. When he took a French fry off a friend’s plate, the other man left the rest of them untouched. A few sought Callen out and asked if some small malady was by any chance an early sign of AIDS. “At first, people would be real nice and say, ‘Oh, how are you?’ ” Callen says. “Then they would say, ‘Could you look at this little sore?’ ”

A slight fever or a bit of congestion was enough to send hundreds of others to physicians. A number of homosexuals consulted Dr. Kean. He recalls, “They say, What can I do?’ I say, ‘The best thing to do is get married.’ ” Other panicked men filled the West 57th Street office of Dr. Dan William. Usually, the complaint turned out to be just a cold or a touch of flu that served the patient with a warning to stay out of the baths and other places of random sex.

“I’d rather have a patient who is a little panicky or neurotic and is also alive five years from now than to have somebody who has his head in the sand and dies,” William says. “You can treat panic and neuroses.”

The medical charts of the men in the city who frequented the baths began to read like something out of Biafra.

Then, in greater and greater numbers, there were the ones who came into the office with a symptom that was more than just a scare. Many said they had spent considerable time in the baths. Others said they pursued quiet lives with few sexual adventures. For them, AIDS may have been less the result of an unfortunate life-style than of unfortunate luck. William would tell the patient to eat intelligently, avoid alcohol and drugs, refrain from smoking, and keep away from crowded places where he might pick up infections. There was no treatment for the disorder itself, and all William could do was watch the patient’s immune system disintegrate.

“People say, ‘Give me a pill, give me a shot, make me better,’ ” William says. “People believe that there is a simple answer for everything. People are very naïve.”

After being diagnosed, one 24-year-old AIDS patient was driven from his family’s home and left to live on the street. Another was evicted by his lover and forced to sleep in hallways while he had a fever of 104 degrees. When one patient died, his family refused to claim his body. A patient named Arthur Felson was fortunate enough to have a friend who stuck by him. Then the friend saw an erroneous report on television that the illness could be spread by everyday household contact. Terror of the disease apparently drove the friend to commit suicide.

“I just couldn’t shake it out of him,” Felson says.

In many hospitals, AIDS patients were placed in isolation. Nurses entered the rooms wearing gowns and gloves. A number also wore surgical masks. At the Veterans Administration Medical Center on First Avenue, some of the staff were reluctant to bathe the AIDS patients. Others had to be prodded to change the beds. One patient at Bellevue Hospital heard a knock and opened his door to discover that somebody had left his food tray on the floor and then fled. A patient at another hospital was told by his doctor that he could leave and go home to die, but was unable to find a housekeeper who was willing to risk exposure to AIDS.

At Lenox Hill Hospital, a nurse named Deborah Curran noticed that some of the technicians avoided drawing blood from AIDS patients. “A lot of times, they say, ‘I can’t get it.’ A lot of times, they don’t even try, and then some doctor has to do it,” she says. Curran herself felt the fear of contagion for the first time in her five years as a nurse when she was asked to remove an intravenous tube from a young man with AIDS.

“I didn’t even breathe until I walked out,” Curran says. “I walked in, and he was staring right at me, watching every move I made. I said, ‘I’m going to take out your IV,’ and he said ‘Okay.’ That was the only thing I said. I didn’t want to say anything else and have to breathe in.

At St. Vincent’s Hospital, a student nurse named Claudia Cozzi was assigned to a ward that housed as many as seven AIDS patients at a time. During one shift, another student accidentally stuck herself with a needle that had been used on one of the AIDS patients. Cozzi describes the moments that followed as “pandemonium.” The student was given a gamma-globulin shot, and then there was nothing to do but wait two years to see if she had contracted the illness.

Reassuring herself that no health-care worker had yet caught AIDS from a patient, Cozzi fetched ice packs for some and went to the cafeteria with special food orders for others. Often, she just stood by a bed and listened to a patient talk. Many spoke of their families. Others said they wished they had not been homosexual. Some refused to eat, and said they would rather kill themselves than continue to suffer. A few tried to deny that they were ill. They got out of bed and smoked cigarettes and wrote letters and made telephone calls until they were too weak to move.

Even with the odds of contracting AIDS from contaminated blood at less than one in a million, worried calls kept coming into the office.

“They get a daily weight check, and they just waste away,” Cozzi says. “They all know the outcome. That’s the trouble. They all know they’re going to die.”

One afternoon, Dr. Joyce Wallace, of the AIDS Foundation, sent Cozzi to the Federal Express office on Seventh Avenue with a padded envelope containing three biopsies. When the clerk saw the letters “AIDS” in the return address, he froze. He asked Cozzi to empty the envelope and she pulled out the three test tubes. “He said, ‘Oh my God, this is what everyone’s talking about,’ ” she remembers. “I said, ‘Relax, I’d be the first one to get it between the two of us.”

Sent to the main office on Eleventh Avenue, Cozzi presented her package to a supervisor. She remembers, “He said, ‘Oh, you’re the one who’s got AIDS.’ There were ten people in the room, and everybody shifted to the other side like I had leprosy.” The supervisor picked up a telephone and called the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta. A moment later, he turned to Cozzi and said that the C.D.C. wondered how she thought the AIDS material should be marked.

“He wouldn’t even let me touch the phone,” Cozzi says. “I said, ‘Label it “Cancer.” ’ ”

Hanging up the phone, the supervisor said the C.D.C. had determined that the material could be shipped if it was labeled as a carcinogen. “He said, ‘We’ll put it in some extra boxes, just to be sure,’ ” Cozzi remembers. Even after she put the test tubes in four boxes, Federal Express apparently had some difficulty convincing its workers to move the AIDS material any farther. The test tubes did not reach their destination for four days.

At the Greater New York Blood Program, the symptoms of AIDS were added to the screening questionnaire. Those who passed were then asked to disqualify themselves if they were members of one of the primary risk groups. This form was then folded three times, stapled closed, and coded with the type and character of the blood. Later, a lab technician studied the form and any blood then deemed potentially hazardous was set aside for research. Still, even with all the precautions, even with the odds of contracting AIDS from contaminated blood at less than one in a million, worried calls kept coming into the office of the facility’s medical director, Dr. Robert L. Hirsch.

“We get calls from just about every walk of life,” Hirsch says. “You’ve got to waffle. There’s little you can tell them. There’s so little we know.”

Over at the Emergency Medical Service, officials began preparing a memorandum advising ambulance medics to wash down any equipment that came in contact with somebody who might have AIDS. There was also talk that the city was considering the purchase of “S-tubes” that would protect those who had to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. An emergency medical technician named Eileen Sullivan read a pamphlet on AIDS and began using disposable gloves when she encountered someone who was bleeding. If a call involved somebody she suspected was gay or a junkie, she threw out any of the cheaper equipment she had employed. She soaked everything with alcohol for the rest of the day.

“We’re very paranoid about it,” Sullivan says.

In the 6th Precinct, a young police officer found herself frightened as she assisted a homosexual who had injured his head in a fall. She cradled the man’s head in her hands and attempted to slow the bleeding with a wad of napkins. She remembers, “At first, you feel itchy. The blood was the same color red, but I thought, ‘Oh, wow, I wonder if this guy’s got it.’ Then I thought, ‘Oh well, I can’t let this guy bleed to death.’ It was like a leper or something. You don’t treat people like that, but the fear is there. I found myself scrubbing with peroxide.”

During another tour, the officer arrested a man who had stolen some enamel plates from an antiques store in Greenwich Village. On the way to the station house, she rode in the backseat with her prisoner. She recalls, “He said, ‘I’ve got AIDS.’ I said, ‘Gee, I’m sorry to hear that, but I’d think you’d find a better way to spend the rest of your time.’ He said, ‘I need the money. I have a date tonight.’ ” Later, hearing that the thief had AIDS, the shopkeeper decided to drop the charges.

And as a medical technician reached for gloves and a cop scrubbed with peroxide, there was still no word of a cure. The casualties were limited to a few hundred homosexuals, junkies, and Haitians, and the government seemed reluctant to fund research. Dr. Linda Laubenstein, of New York University Hospital, says, “Don’t say there wasn’t enough money; say there wasn’t any money.” As the threat grew and the number of victims topped 1,000 nationwide, the U.S. Public Health Service suddenly called AIDS “the number-one priority.” The National Institutes of Health and the federal Centers for Disease Control put up $14.1 million for research in 1983 and pledged another $16.7 million for the next year.

At the AIDS Foundation, virologist Dr. Joseph Sonnabend suggested that the syndrome was the result of repeated exposure to a common virus, such as cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus. At New York Hospital, Dr. B. H. Kean theorized that AIDS was the work of a virus that had mutated into a more virulent form as it was passed rapidly from host to host. At Downstate Medical Center, Dr. Sheldon Landesman said that some scientists were speculating that a new virus might have been introduced from equatorial Africa or some other remote part of the world. At Harvard University, researchers pointed to the human -T - cell - leukemia virus.

As the threat grew and the number of victims topped 1,000, the United States Public Health Service called AIDS “the number - one priority.”

In the hospitals, physicians tried to fight the illness with chemotherapy, bone-marrow transplants, interferon, and a filtering of the blood known as plasmapheresis. Nothing worked, and the number of victims was growing every few hours. Twelve of Dr. Dan William’s patients died. Up at Westchester Medical Center, a neurosurgeon named Thomas Lansen removed a brain abscess from a 29-year-old AIDS patient only to see a second abscess develop a week later. Lansen went home that night saying he wished he did not have to operate on an AIDS case ever again.

“None of these people are getting better,” Lansen says. “You can’t help feeling that the operations we are doing are futile, but you have to try.”

Four inmates contracted AIDS at Rikers Island. Three died at Auburn prison, and 100 inmates there went on a hunger strike demanding that all homosexuals be banned from the kitchen. The state correction officers asked for protective masks and called for the isolation of all prisoners with AIDS.

After two members of the Metropolitan Opera company contracted the illness, baritone Gene Boucher drew up a flier listing the symptoms of AIDS. The flier was distributed by the American Guild of Musical Artists, and a copy was posted at the New York City Ballet. Some stationery stores began stocking AIDS cards. The outside of one card read, “Sick? While you are getting well …” The inside read, “Make a list of all the people you’ve infected.”

At the city Bureau of Preventable Disease, the telephone began ringing as many as 50 times a day with inquiries from fearful citizens. One caller was reassured that mosquitoes are not known to carry AIDS. Another was told that there is no reason to fire a maid simply because she is Haitian. One doctor who works at the office was stopped by a neighbor who wanted to know if it was still safe to visit Greenwich Village. Another neighbor asked if she should worry about working with a homosexual.

And there were a thousand other stories of fear. Dr. James Oleske received a call asking if it was risky to invite a homosexual relative who had AIDS to a christening. The widow of musician Charles Mingus found herself wondering if she should continue to swim in her building’s pool. “When I was growing up, polio was still killing people, and mothers wouldn’t let children swim in pools,” Susan Mingus says.

At St. Vincent’s Hospital, Dr. Joyce Wallace was called by a Wall Street firm that had an employee who had AIDS. Wallace remembers, “They said, ‘Everybody is hysterical. He says he has AIDS. Other people don’t want to work with him. How do we protect ourselves.’ I said, ‘Don’t sleep with him, and don’t share a needle with him.’ “

On Long Island, a woman confided to a close friend that her husband had come down with AIDS. Suddenly, none of the neighbors wanted their children to play with the woman’s daughter. The friend pressured the woman to take the daughter out of school. The sanitation men refused to pick up the woman’s garbage. She finally called the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and asked a psychotherapist named Diego López for help. López served as a marine in Vietnam, and the woman’s tale reminded him of the reaction of people in combat.

“When people are afraid, they create horrible things in their minds that don’t exist,” López says.

Back in Manhattan, a health fair that planned to offer examinations for AIDS was bounced at the last minute from P.S. 41. The school-district superintendent expressed fears that the cafeteria would be contaminated. The fair opened at a nearby community center. One woman came in and asked if her daughter was in danger of getting AIDS by attending a synagogue with homosexuals.

In midtown, advertising executive Karen Smith found herself discussing AIDS with some colleagues over lunch. The talk turned to symptoms, and somebody remarked that one of the agency’s employees had come in with a reddish rash on his upper arms. Somebody else said that the man had recently lost a lot of weight. It was also noted that the man had developed a persistent cough. And Karen Smith suddenly felt less than comfortable to be sitting near the man’s desk.

“I started getting kind of nervous when he coughed or cleared his throat,” Smith says. “I say to myself, ‘What could I be breathing?’ “

A short time later, Smith was required to go over some work with the man. She remembers, “I had to stand close to this person, and I said to myself, ‘Keep calm. Even if he does have it, you’re not in danger.’ Another piece of me said, ‘Run. Turn around now and run. Just get away.’ I held my breath and then told myself, ‘Don’t be ridiculous. This isn’t going to help. You have to breathe sometime.’ Then I turned away and took a breath behind me.”

On another day, Smith went out to lunch with a friend who is homosexual. When it came time for dessert, they decided to split a piece of cheesecake. Smith assumed that the waitress would bring the piece on a single plate. The waitress instead cut the piece in half and served it on two plates. “When we ordered, I didn’t think twice,” she says. “But as I ate I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m so relieved. He could be infected.’ Then I said, ‘Oh, come on.’ You’re at war with yourself.”

Eventually, Smith discussed her anxieties with her psychoanalyst. During the session, the psychoanalyst handed Smith a copy of a newsletter concerning AIDS. “My shrink said she’s eating home a lot more. She’s worried about AIDS, too,” Smith remembers.

Invited to testify on the illness before a legislative hearing, Callen was told, “Don’tbring any AIDS patients.”

The death toll in New York reached 288. This included a prominent Brazilian fashion designer named Marcus Goncalves. Yet there are still crowds at the baths, which some New York doctors believe helped spread acquired immune deficiency syndrome in this city. Here men lounge with towels wrapped around their waists and slip into cubicles for sex whose hazards Dr. Dan William compares to driving a car at 120 m.p.h. while inebriated. At the Everard Spa, owner Irving Fine reports that business is down just 10 percent.

“You lost your business people, your married men,” Fine says. “And you can’t blame them.”

At the East Side Sauna, on 56th Street, the crowds tend to dwindle when AIDS is in the news. Then, after a few days, the men drift back. Manager Jim Schwartz says, “Certain people, when you start to talk about it, they leave. They want to be as ignorant about it as they can.” Schwartz now supplies prophylactics and uses a stronger germicide on the tiles.

“I know it won’t do a hell of a lot, but you do what you can,” Schwartz says.

Then there are the brothels, and the swingers’ clubs, such as Plato’s Retreat. There are doctors who feel that the sex that occurs here may soon prove to be as deadly as that in the baths. Dr. William says, “You can be absolutely certain the single swingers will likewise be affected by AIDS. It’s just a question of time. It’s just a question of the right person with the infectious agent. And then it’s just a jump into mainstream America.”

Among those who now feel safe is model Susi Gilder. Over a gulf-shrimp dinner at the Texarkana restaurant, on West 10th Street, she extracted a pledge of monogamy from her boyfriend, Eddie. When Susi made a visit to the ladies’ room, Eddie said, “I’ve been reformed by the Black Death.”

And among those AIDS patients who still survive is Michael Callen. In May, he was invited to testify before a legislative hearing on AIDS headed by State Senator Roy Goodman. Shortly before the meeting, an assistant called to ask Callen if he planned to bring anybody with him. Callen said he would be happy to round up some other AIDS patients.

“He said, ‘Oh, don’t bring any AIDS patients,’ ” Callen says.

A few days later, Callen was having breakfast with his lover in a coffee shop on Sixth Avenue. The lover is a drummer from Chicago named Richard Dworkin. The two men first met a year ago, when Callen decided to use the time he had once spent at the baths to form a gay band. He put an advertisement in a local paper, and Dworkin was one of those who answered. One night, Dworkin stayed late at Callen’s apartment. Callen remembers, “He made this pass at me. I was so shocked. I said, ‘Wait, stop, you don’t know. I’ve got AIDS.’ ” Dworkin decided that he was willing to take the risk, and the two men grew devoted to each other. After the bowling alleys and the toilet stalls and the baths, Michael Callen now lives whatever days he has left much like a good Methodist from Ohio.

“Love’s a funny thing,” Richard Dworkin says.