High in the air, swirling above the grand riv-vu buildings of the Upper West Side, they were birds of prey: part of nature but not part of us. Closer to the ground, they might as well have been human. Perhaps that was because they were living a familiar New York real-estate story. Like many couples, this pair of red-tailed hawks, even in their first season together, knew where they wanted to be. The way the Upper East Side or Tribeca call out to some, Riverside Park called out to them. Or did it only call to her, and he simply went along? It wouldn’t be the first time such a thing was observed in nature. After all, she was older, by a few years; he still had the bright eyes and playful habits of the adoring younger male.

But she was all business. She would have understood that the neighborhood was far enough from kin and competitors to suggest they could make it their own. It featured unimpeded Hudson vistas, fine dining, and protected areas that seemed perfect for raising a family. That was important: February was almost over, and in April, if all went well, they would be parents. How could they foresee, with brains smaller than their eyes, that the needs of other parents in the neighborhood, other offspring, would come to trump theirs?

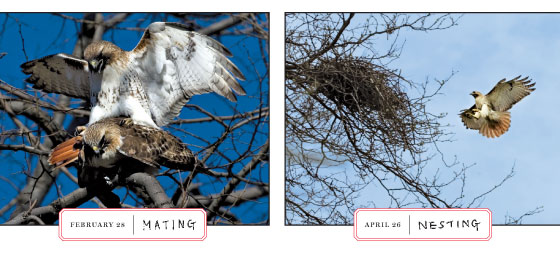

Work began on the nest at once. You might charitably have called it a fixer-upper, even though it was new construction. It was too far out, some said, on a too-low branch of a honey-locust tree, overhanging the northbound on-ramp of the West Side Highway at what would be 81st Street. Cars zoomed almost directly underneath, belching fumes. Wind and rain set it swaying.

Still, this was an idyllic time for the airborne pair, and also for the cooing and clucking humans below. The birds’ arrival in Riverside Park came at a moment when life was full of promise for urban raptors. Their population had never seemed greater. After the disturbing saga of Pale Male and Lola—those alpha red-tails of Manhattan society, whose twelfth-floor nest at 927 Fifth Avenue was removed by the building’s co-op board in 2004—this felt like a fresh start. That pair had become a cause célèbre, complete with tabloids, tragedy, and Mary Tyler Moore. This new pair, younger and closer to the ground, was a simpler gift, seemingly without history.

And so they immediately attracted the city’s most avid citizen-scientists. Those who led the welcome wagon in Riverside Park were themselves a taxonomy of types: the white woman with the flame-red hair and pooch on a leash, the older woman with the big glasses, the black man with the telescopic lenses on his camera. Here they hovered, sometimes several hours at a time or several times a day, watching, photographing, giving impromptu seminars to Sunday parents and excitable children, then e-mailing and blogging the latest news deep into the evening.

At first, nest-building was their main topic of interest. Each time the male arrived with a beakload of twigs, as if from Home Depot, there were pictures and descriptions of the event. When the female wove those twigs into the nest, that was an opportunity to reflect on the pair’s uncanny cooperation. To the red-tail groupies, it was almost as if a constant stream of interpretation were necessary to the project’s success. They were not just observing but in a way creating a dramatic serial, like Meerkat Manor, only right here in our backyard. They were telling a story of life as it should be—not that they would express it that way. To them, it was unfathomable that everybody didn’t rush out to witness the existence of creatures so innately wondrous. Grandeur was a word often heard in the park.

But except for their enormous wingspan, red-tails aren’t actually very big: only two feet long, three or four pounds, the females somewhat larger than the males. And they’re not all that colorful despite their taxi-yellow feet and namesake tail feathers, brick from above, pinkish from underneath. Though gargoyle-impressive when perched on a lamppost, magnificent in combat, they would seem unripe for anthropomorphizing, lacking as they do all softness and facial expression. Mostly they look like Botoxed party ladies, keeping an eye on the door: grand, yes, but in the beady manner of Elaine Stritch. Still, the tilt of their prehistoric heads, the ruffle and soar of their flight, the daredevilry of their 100-mph dives all imply, to those susceptible, feelings if not emotions. Not to mention their unexpected, precarious presence in the city, which makes those feelings seem familiar. We are all unexpected and precarious in New York.

If such projections disturb you, don’t even think about the names. Back in spring, when weekend mornings near the nest were sometimes like press conferences, the Riverside Park Fund ran a contest to christen the hawks. It might have been a contest to christen puppies. Among the 68 entries there were no Killers or Blitzers or Bunyanesque Eat-or-Be-Eatens. Rather, entrants gravitated toward the comfort of inevitable pairings and unlikely reconciliations. Ozzie and Harriet. Peanut Butter and Jelly. Jerry and Elaine. Hillary and Obama.

Some of the Riverside observers favored Henry and Katherine Hudson to win, though this made the hawks sound less like birds than Wasps. Or perhaps that was the point. Names given to other red-tail pairs around the city were a bit too fragrant: Athena and Atlas near Astoria, Alice and Ralph in Prospect Park, Big Mama and Junior in Green-Wood Cemetery, Tristan and Isolde at St. John the Divine. The new pair, whose domain covered the far West Side from about 72nd Street to 125th, abutting Tristan and Isolde’s, deserved something more classic, befitting local royalty, which is to say celebrity. After all, as Lincoln Karim—the Trinidadian with the telescopic lens—was the first to identify, one of them was a descendant of Pale Male himself.

Of course, Karim might have been wrong. There are ways to differentiate individual red-tails by feather pattern, size, and coloration, but even experienced observers may have trouble doing it, let alone fixing bloodlines. And Karim, normally sweet and soft-spoken, is excitable. During the Pale Male Passion Play, he was arrested (and briefly suspended from his job as a television-broadcast engineer at the Associated Press) for allegedly stalking Paula Zahn, a resident of 927 Fifth, and scaring her children by shouting, “House of shame! Bring back the nest!” Though the charges were dropped and the birds eventually allowed to rebuild, the new nest has not succeeded in the four years since, as Karim frequently laments on his Website.

His crush on Pale Male may have clouded Karim’s thinking about other hawks. To his embarrassment, the Riverside red-tail he at first proclaimed as The Great One’s son turned out to be female. He realized this one day in early March, when amid the usual steam-whistle shrieking and aerial display, she got mounted by her mate.

Anyway, it made a better story: the sympathetic daughter, or granddaughter, of the patriarch, now striking out on her own. Katherine (as we might as well call her) became a local holy, the raptor Caroline Kennedy.

Their sexes and lineage agreed upon, the Hudsons spent the rest of March mating and decorating. More time was spent on the latter. Copulation, though frequent, was over almost before it began, as some observers noted with disappointment. Hard to make that ten-second act—Katherine tilting down as if looking for a contact lens, Henry standing on her back, clawing her shoulders—seem noble, though at least hawks are, like some humans, monogamous. Nor was the nest everything it might be; seeming to lack a sense of proportion, the pair didn’t stop until it was almost three feet wide and listing. But no one cared about that once Katherine, over the course of a few days near the end of the month, produced her eggs. One, two, three.

Not that any humans yet knew that; from the ground, the eggs were impossible to see. Nor could photographers find a perch high and unobstructed enough to let them spy into the shadowy nest. Still, the reaction among the hawk-lovers was not unlike that among grandparents of a fetus recently detected in a sonogram. Everyone understood what it meant that Katherine sat there continuously, shifting and checking beneath her, occasionally spelled by Henry when she needed to stretch her wings. The naturalists among the crowd knew further that the timing was right. This was when most New York City red-tails laid eggs; four or five weeks later, they sometimes hatched.

It wasn’t a lot to go on, but even that much natural history was remarkable. Before Pale Male began roosting on buildings around Central Park in the early nineties, no other red-tailed hawks were known to have made the human architecture of the city their home. There was no record of their urban habits because they had none, even though they thrived nearly everywhere else in North America. To New Yorkers, a red-tailed hawk might as well have been a thing of the primordial past or sylvan distance, and possibly better that way.

But Pale Male, born who knows where around 1990, changed all that. From 1995 to 2001, with serial mates named First Love, Chocolate, and Blue, who each predeceased him, he sired twenty eyases (as raptor chicks are called) and then another seven with Lola before the ruckus of 2004 ended his streak. Some attribute the failure of his fecundity to the spikes installed by the repentant co-op to stabilize the new nest he and Lola built. Or the culprit may simply be age. At 18, Pale Male has reached the average life span of red-tails in the wild, though no one knows how long they might survive in the city, where there is so much food available year-round: squirrels, pigeons, robins, and of course mice and rats. Already, having no need to winter elsewhere, many have stopped migrating.

In any case, Pale Male had done his part: Last year, the Audubon Society counted 32 nesting pairs around the city, many of them presumably his descendants. And by this spring, with at least eight viable nests in Manhattan alone, his line seemed set to flourish further.

Parenthood, even someone else’s, does strange things to people. More than a few humans have been humanized by it. Animal parenting, if cute enough, ups the ante, making the alien normal, what was disgusting delightful. Wildlife and our life are briefly synonymous. Because they’d been told of eggs in the nest, children with nannies and visitors en route to the Boat Basin Café watched with strangely equal pleasure as the Hudsons bathed in morning puddles or gobbled bloody bits of rat.

Leslie Day, with the flame-red hair, knew all about this. There are 70 animals in her classroom at the Elisabeth Morrow School across the river in Englewood, New Jersey, where she teaches fifth-grade and eighth-grade life science. Three more (if you don’t count her husband, a biology professor) live with her on the Sanibel, a cramped but cozy 43-foot houseboat moored at the 79th Street Boat Basin. There’s Sadie, a terrier-schnauzer mix, who first led Day to the Hudsons’ nest. There’s Paulie, a cockatiel. And there’s Woody, a cat who is now in mourning for a recently deceased companion named Cosmo. Woody hangs on to anyone, even visitors. For Day, it’s a given that warm-blooded animals, whether cats or hawks, have feelings—if caring for something, mourning its loss, is a feeling.

Day is certainly warm-blooded. Her passion for wildlife, which culminated in her Field Guide to the Natural World of New York City, can be traced to the early eighties, when a female northern cardinal befriended her, and thence to childhood Sundays in Central Park with her grandmother. But the red-tail saga seemed to reveal significant blood-temperature variation among humans. Some rooted for the breed as if their enthusiasm could influence the outcome. Others found the intruders an unmitigated nuisance. Most, perhaps, fell in between. But none could be pigeonholed by external markers like wealth or vegetarianism. As a group, those who treasure the birds do share certain traits: all gentle, most liberal, some childless—but that is another nest we cannot spy into.

It’s not just humans who benefit from public invisibility. Despite sidewalk vigils, the date of the Hudsons’ blessed event can only be estimated, because, unlike some celebrity couples, they kept their newborns away from prying eyes. It was instinct, not propriety, if those things are different, that prompted their reserve; hawks are altricial, born helpless in trees, nearly naked of feathers, eyes fast shut. If nothing can see them, nothing can eat them.

What could be seen, starting around Earth Day, April 22, was the obvious parental behavior. Every few hours, Henry, after eating in a nearby tree, delivered leftover chunks of meat to Katherine in the nest; she tore the meal into smaller bits with her beak and gently dropped them within. (The inedible remains, often dumped near Riverside Drive, looked to one observer like old fur coats with legs.) Surely there were eyases, but how many? Even the Riverside regulars couldn’t say.

And then, one day at the end of April, an eyas now old enough to work its neck popped its head briefly over the lip of the nest. Soon a second followed and, after a few days of uncertainty and careful photo research, a documented third. If the anthropomorphosis of the birds had bordered on extreme before, the establishment of a family unit inflated it to Greek proportions. The eyases’ fuzzy Q-tip heads, perched atop silly llama necks, would defeat even Disney in a contest for heart-pulling cuteness. Though it takes many weeks for red-tails to fledge fully, they are quite active once they open their eyes; soon after their public debut, the baby Hudsons were walking around the nest, jumping up and down, testing their as-yet-useless wings.

The effect was hypnotic. Karim posted daily updates on his Website. Day ran from her houseboat to see them even in the rain. Beth Bergman, of the big glasses—a freelance photographer who for 40 years has documented divas and dramas at the Metropolitan Opera—took a thousand frames of the happy nest. She was stunned by the tenderness of what she thought of as gentle giants: the way the mother looked right into her babies’ eyes while feeding them, the sensitivity and integrity of their domestic arrangements. Yes, they occasionally pooped all over while she set up a shot, but, all things considered, they did not suffer by comparison with her usual quarry.

If this were indeed an opera it would be La Bohème, its first two acts bursting with high-spirited scrappers making their way in the city. But Puccini also wrote Acts III and IV.

The nest started to droop after a heavy rain on Friday, May 9. On Saturday, Bergman spent five hours watching in vain for any sign of the babies. Karim did see Henry drop two rats into the nest, but not the subsequent feeding frenzy. Henry’s behavior was odd in general. He delivered branches randomly to other trees. At one point he walked right onto the highway on-ramp to gather twigs; Karim leaped over the railing to chase him from danger. Meanwhile, Katherine kept looking into the nest, then flying away. Her posture, Karim thought, could only be described as sad.

The next morning—Mother’s Day, it would turn out—Katherine flew from the nest as she had often done after feeding, to remove a carcass and keep her home clean. Only this time it was not the remains of a rat but one of her eyases she bore limp to the ground. Presumably during the night it had died. Did she have what Day would call feelings? Did some avian version of the concept of good-bye pass through her tiny circuitry? Or just the instinct to go on? I will put this down over here. Now I will return. The result was the same, either way. She went on.

Meanwhile, a dog-walker, fearing one of her charges might get at the body, put the eyas in a brown paper bag and left it in a nearby trash can. Day recovered the dead bird later, holding it gently in her palms and crying: a trans-species Pietà. It was perfectly formed, not yet stiff, the size of a chicken, and very soft, its pinfeathers just beginning to grow in. Following Karim’s instructions, she brought it home to the boat and kept it in the refrigerator overnight.

If she was crestfallen, nature itself was blasé. On Monday, Karim took the eyas’s body to the state Wildlife Pathology Unit near Albany; the next day the Hudsons’ nest plummeted to the ground, the other two eyases dead within it. They too were collected for testing, while Day studied the scattered basketwork. Was Friday’s storm to blame? Poor construction? Or was it grief? Karim believed that Katherine had stopped covering the nest once her babies died, letting the rain fill it up like a sink until it collapsed.

Whatever Katherine and Henry felt, they never returned to the site of the nest. But for the humans the deaths were clearly a tragedy, requiring explanation and resolution. The toxicology report on the first eyas concluded that its body contained lethal levels of the rat poisons brodifacoum and bromadiolene. And yet that explanation led to a mystery: A Riverside Park official told Karim that brodifacoum and bromadiolene were not being used within its grounds. A different rat poison, difethialone, also potentially lethal to hawks, is used instead, in baiting stations disguised as rocks.

But just beyond the park’s perimeter, in the moats and planting areas of buildings on 78th and 79th Streets, Karim discovered four black triangular boxes not trying to pass as nature. An official notice advised that these baiting stations had been placed on March 27 by the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and contained Talon G—a commercial rat poison containing brodifacoum. It had only been a month before, according to minutes of a February cabinet meeting of Community Board 7, that residents complained of a rat resurgence. Presumably Henry brought Katherine one or more animals that had visited these stations. Katherine in turn gave them to her eyases, who were too young to withstand the poison’s anticoagulant effect and so bled to death internally. Surely one of the blessings of a small brain is that, whatever else she feels, she will never know she fed them their death.

If, as Karim believes, the Talon G was used in a manner inconsistent with the manufacturer’s label, which prohibits placement in locations accessible to nontarget wildlife, that use may have been illegal. But it’s a hard case to make. What does “accessible” mean? In any event, while some people like and want to protect hawks, few feel the same way about rats, which fall decisively on the wrong end of the grandeur scale. Not that hawks are inherently more cosmopolitan. Each violently defends its territory from other raptors—and from humans. Earlier this year, Isolde attacked construction workers who came too close to her nest at St. John the Divine, sending them to the hospital.

That humans do the same thing—kill to survive, as a Department of Health doctor told Karim—is an equivalence he does not endorse. To him, the hawks are finer, deeper than that. He knows it’s the kind of argument scientists ridicule, but he watched Henry, he says, with his heart: saw him grieve, ripping twigs out of trees as if to exorcise pain. Whereas human beings, smoking, fighting, sticking gum anywhere? Even pigeons are better. Karim watches how bird parents take care of their babies; then he watches human parents.

Perhaps we anthropomorphize other creatures in the hope that someone will anthropomorphize us. Karim is of that breed that believes in and awaits universal reconciliation. But for the problem at hand he sees no likely solution. Despite his postings and calls to authorities, nothing has changed. The baiting stations are still there, outside the park and inside, too. Well, not all of them. One day in May, Karim brought some home from the park to photograph. They don’t make for lovely pictures, but they killed a mouse in his apartment.

No surprise that the natural world is full of death, which is one reason we try to corral it. The hawk stories from Pale Male onward flatter our dream of unlikely survival, even grandeur, in an unwelcoming environment. This spring, New York’s red-tails disappointed that dream. There were more nesting pairs than ever but, as directly follows, more failures too. Some produced no eggs, and some eggs failed to hatch. Even eyases who lived to fledge faced the problem of growing up in an environment not primed to deal with them. They got blown into buildings by heavy winds or picked up by police when neighbors found them practicing their moves on the ground. The U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act never anticipated city hazards, like the construction worker who dropped rocks (he said they were pieces of bread) on Pale Male’s head, or the eyases that succumbed, as some human children do, to lead poisoning.

And the Hudsons? Or perhaps we should no longer call them that, the naming contest having been canceled as a result of their loss, and their identities returned, as it were, to the wild. At the site of their old nest, the flowers and cards are now gone; all that remains is a blurry note taped to a railing, directing visitors to Karim’s Website for information about what happened there. But they aren’t far away. Though Day would not walk in that part of the park anymore, one morning late in May, Sadie dragged her north along a bike path, and there they were, building a new nest, about 300 feet from the first, in a London plane tree nearer the river. It was quite an improvement, real-estate-wise, set firmly in the crotch of four hefty branches. Later, Karim saw them mating there. Nothing resulted, but the humans, at least, appreciated the effort.

And then, by the end of June, the new nest was abandoned. Some think it was built only as grief-work. Others think the hawks were preparing it for next year and will lay eggs there come March. Frequently, from her boat, Day sees the pair in the trees behind the ball field at 77th Street or over the river, alarming flocks of pigeons. This gives her hope that they will return.

Karim isn’t so sure. What makes sense to us may not make sense to them, he feels; we don’t see what they see. Perhaps they’ll find a better spot, where they will be made more welcome. Maybe, he suggested darkly, in New Jersey.

This story relies on news reports as well as the work and thoughts of various hawk-watchers. Leslie Day blogs at fieldguidenyc.com. Lincoln Karim’s observations of red-tails are at palemale.com. Beth Bergman posts her photographs at thebethlenz.blogspot.com. Marie Winn is the author of Red-Tails in Love (1998) and the just-published Central Park in the Dark. D. Bruce Yolton maintains the Website urbanhawks.blogs.com.