Here are three different stories, to be filed under “Don’t be that guy.” They all start differently. And they all end in the same place.

(1) Last fall, a 26-year-old man drew the attention of pedestrians on West 47th Street. He seemed slightly agitated. Finding the door to the Olive Garden locked, he went into Tad’s Steakhouse, briefly climbed onto the counter, then left. As he paced the sidewalk, he checked his cell-phone messages. Other than a single black sock, which he later removed, the cell phone was the only thing he was wearing.

(2) One Sunday a year ago, a daytime-soap actor inclined to volatility found himself at 45th Street and Tenth Avenue at 4:50 a.m. (this was probably already a bad sign), fighting with three people for no apparent reason. After shouting, “I’m going to get you!” he allegedly went after them with a metal crate as a weapon. When the police came, he began flailing and kicking.

(3) In July, a 29-year-old resident of West Hartford, Connecticut, decided to pay a visit to New York City, specifically to the new New York Times Building. He thought he’d like to see the view from the top, without the aid of an elevator. Using the horizontal ceramic rods on the building’s exterior that were part of Renzo Piano’s design, he began to climb. When he reached the tenth-floor ledge, he stopped to rest and called an editor at the Daily News. The police arrived and placed a large inflatable cushion on the sidewalk in case he jumped or fell. It was past 5 a.m. when they finally talked him down.

There are countless ways to go crazy in New York City—permanently or briefly, bloodily or peacefully, comically or horribly—but those among us who have ever wondered if our own names might one day be called in that unlucky lottery are generally aware of a key distinction: You can lose it privately or you can lose it publicly. Losing it privately can be resolved by a call to your shrink, or the intervention of family, friends, and colleagues, or medication, or a stay in a private mental-health facility. But if you’re in Manhattan and you happen to be unfortunate enough to decompensate in a manner that involves an imminent threat to yourself or those around you, your day is probably going to end the way it ended for all three of the aforementioned gentlemen: You are going to Bellevue. Bellevue will almost certainly not be the last stop on your personal journey, but it is the single word that, for more than a century, has told the rest of New York City that there is now one less person on the streets about whom it has to worry.

“It takes a lot to get into Bellevue,” says Frederick Covan, who arrived at the hospital in 1980 and served as its chief psychologist until 1994. More accurate, it takes the absence of any alternatives. Bellevue is not for “some Upper East Side suicidal neurotic or whatever—they’d go to NYU Medical Center next door. Our patients were the ones with no money, no resources, and multiple stressors.”

That, or their behavior is so extreme—criminal or otherwise—that no other option presents itself. Merely wandering into the middle of Broadway while muttering incoherently? Probably not enough. “You know, the brilliance of the schizophrenics when they’re directing traffic,” says Covan, “is that they always direct it in the direction it’s already going, so their grandiosity is reinforced. But if they start to direct it in the opposite direction, or if they’re assaulting other people, or if you came in and said you really wanted to kill yourself, not just that you were thinking about it … You know, Bellevue is not the place for you if you’re just not feeling good today and you’re really worried about the stock market.”

The newer buildings of Bellevue sprawl across a few blocks on the east side of First Avenue in the high Twenties. Spokesmen for the hospital will remind you, with the dogged patience of those who have had to say it again and again, that Bellevue is much more than a psychiatric center—it’s the oldest public hospital in the United States (dating to 1736, when it was founded as a six-bed almshouse). Last year, nearly 2,000 babies were born there.

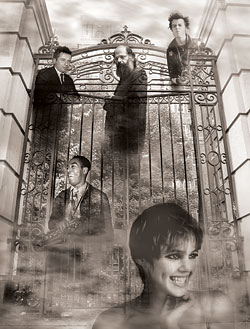

But the Bellevue of our shared imagination—the nuthouse, the punch line, the must-to-avoid vacation spot—is something else entirely. And at least in one sense, it’s about to go away. Although Bellevue’s mental-health treatment center will continue to operate at full strength, this spring, the city’s Economic Development Corporation announced its intention to offer up the building that, for more than half of the last century, was Bellevue. Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital, the Bellevue that for 78 years has stood, gloomy and gated, on 30th and First, the Bellevue made infamous in movies and nightmares, the forbidding destination for so many celebrated and notorious New Yorkers that it stands as a chilling landmark: the Chelsea Hotel of the mad.

The plan is to attract developers with an interest in turning the building into a hotel and conference center, which could serve as a hub for the area’s medical community and the East River Science Park now under construction. The EDC’s request for proposals points out that the building’s H-shaped layout—long hallways, small rooms—makes it a natural for redevelopment. The rooms at the ends of each leg of the H could be especially large and commodious. Those used to be the locked wards.

Yesterday’s asylum, tomorrow’s boutique hotel: It sounds like either a joke or a one-sentence history of Manhattan real estate. (Much of Columbia University, after all, was built on the grounds of the former Bloomingdale Insane Asylum.) When the news broke, there was an initial wave of you-gotta-be-kidding. They weren’t. On the contrary, according to spokeswoman Janel Patterson, the EDC received so many proposals by the June deadline that it spent the summer winnowing them down.

The old Bellevue Psychiatric is mostly empty now. A men’s shelter there is closing, an intake center for families in need is moving, and the rest of the building has been largely unused since 1984, when the hospital moved to newer quarters to the south.

And these days, it resembles nothing so much as a haunted house that has tried its best to cheer up and smile. Built in 1931 by Charles B. Meyers, an architect who seems to have specialized in places you don’t want to be (he also helped design the Criminal Courts Building on Centre Street), it’s nine stories of red brick with a perimeter of grass and, on two sides, a low wall topped with tall, spiked wrought-iron fences that look like they were designed to reassure local residents that nobody was getting out. Inside, the main stairwell was once lined with WPA murals, now hidden beneath layers of institutional yellow and gray paint. Outside, vines cover the brickwork, and in the summer the west courtyard is overgrown with black-eyed Susans. A while ago, somebody had the bright idea to remove the diamond-crosshatched steel grates that gave the first floor its prisonlike look. They boarded up the windows and painted benign images on the plywood—a zoo animal, a flowing fountain.

It was a nice try.

Alice: I’ll go fix my lipstick. I won’t be gone long, Killer. I call you Killer ’cause you slay me.

Ralph: And I’m calling Bellevue ’cause you’re nuts!

—The Honeymooners

By the fifties, Bellevue—at least, the idea of Bellevue—was entrenched in pop culture. It was the place where the alcoholic writer played by Ray Milland in the 1945 Best Picture winner The Lost Weekend hit bottom, sweating it out in the locked men’s alcoholic ward. Milland spent a night there to prepare for his role and later recalled the darkness of the dormitory’s being pierced by “a long, undulating howl … the sound coyotes make at night in the high deserts of Arizona” that spread from inmate to inmate. Bellevue is also where the cops took Kris Kringle in 1947’s Miracle on 34th Street while he awaited a court hearing on the subject of whether Santa Claus was real.

But for Manhattanites, Bellevue had started to become a character in the ongoing melodrama of New York City decades earlier. Bellevue opened its first “pavilion for the insane” in 1879 and its first alcoholic ward in 1892. It was not a pretty picture; Jacob Riis included images of the conditions he found there in the lantern slide shows that he eventually compiled into How the Other Half Lives.

It wasn’t just the suffering of the “other half” that fascinated New Yorkers. Between 1890 and 1930, newspapers, led with surprisingly lurid gusto by the New York Times, published blow-by-blow accounts, sometimes in many installments, of any number of unfortunates who found themselves behind Bellevue’s walls.

Some of the stories had the contours of a Henry James novella. In 1894, fascinated readers could follow the saga of Mrs. Margaret A. Harrison, “a handsome white-haired woman” of 83 who was sitting on an estate valued at up to $100,000 but preferred to live in a boardinghouse on East 20th Street. When her estranged daughter heard that her mother was flirting with a fellow resident—an accountant 40 years her junior—and that large sums were mysteriously disappearing from her strongbox, she had her mother packed off to Bellevue, where she was swiftly declared senile by members of what was then called the State Lunacy Commission. Mrs. Harrison’s neighbors rose in fury to her defense, attesting to her “gentle manner and sweet disposition.” There were hints that her daughter, whose husband worked in dry goods, was acting with unseemly haste. “Old Mrs. Harrison’s Friends Indignant at Her Treatment,” blared the headline.

The traffic to Bellevue provided readers with morality plays, parables of the fallen mighty, and gossip that reassured them that dreadful things could happen even to the famous. There was the story of former world chess champion William Steinitz, who in 1900 succumbed to the delusion that he was immensely wealthy and could become more so by inventing a wireless telephone (good idea) that would be operated entirely by willpower (time to call Bellevue). He started giving away the little money he had to street urchins and later became violent. Taken to Bellevue, he died a few months later. “Defeat Broke His Spirit,” announced the Times, which felt free to make the diagnosis that Steinitz’s madness had been caused by losing his chess title to a younger man.

A dose of barely concealed glee was intermingled with a tone of faux concern—still a very familiar journalistic combination—in the Times’ account of the woes of Mrs. John King Van Rensselaer, “a member of one of the oldest and most respected families in New York and Philadelphia.” One day in 1908, she received a nasty letter from her estranged son in which he called her “a selfish peacock, whose name in these times amounts to nothing,” demanded $5,000, and added, “Did it ever occur to you that … by blowing your head off my wife would have an income sufficient to support her? I will take that course if necessary … I am now in no humor to be trifled with.” Neither was Mrs. Van Rensselaer, who had the police take him to Bellevue, declining to interrupt her Catskills vacation to deal with it in person. (This being society, the matter was wrapped up tidily; Mrs. Van R. eventually forgave her son, after he had promised not to misbehave again and said he would “take a farm in the country.”)

Every generation has seen its bleakest self-image reflected in stories of Bellevue.

But for everything that reads like a proto–Dominick Dunne amusement, there are more haunting stories that evoke unmoored, lonely lives. Violet Whittemore was a young lawyer with an active practice in 1914 when she suddenly closed her office in the Metropolitan Life Building. A year later, she was found wandering around Ninth Avenue, waving her hands over the heads of passersby and imagining that she could control their actions. Zelda Crosby was a young woman who changed her name from Shuster and moved from the Bronx to Manhattan after World War I, hoping to make it in the movie business. She lived alone in an apartment on East 55th Street, where she made a living as a silent-film writer for the Lasky-Famous Players Company. Jilted by a producer, she overdosed on Veronal, one of the first widely marketed barbiturates, was taken to Bellevue, and never recovered. The names and details may seem quaint, but they also serve as harrowing reminders that New York has always been a city in which it is frighteningly possible to slip off the tracks, to find oneself adrift. To get lost.

“This was indeed the corridor, the place for walking. It was yellow and green and brown and black; it was neither very long nor very wide, but it was immensely crowded with men of all ages … He felt warm grit under his feet until he stepped on something slick; then he saw that the black floor ahead was scattered with gobs of phlegm. A few of the walking men wore dirty paper slippers, and he envied them; a few were smoking, with packs of cigarettes in their pajama-top pockets … Then he saw that some weren’t wearing pajama tops but straitjackets, and he wanted to whimper like a child. … The light outside was drab—either an early gray morning or a late gray afternoon—and there was nothing to see but air shafts and windowless walls.”

—Richard Yates, describing a Bellevue men’s ward in Disturbing the Peace

By the time Bellevue’s new psychiatric hospital opened, in 1931, the city was in the maw of the Depression; as Sandra Opdycke notes in her history of the city’s public hospitals, No One Was Turned Away, private hospitals had begun to decline to accept charity cases, and almost half of the city’s residents were poor enough to qualify for care in public facilities. Bellevue was the place you went when nobody else would take you in. To those who worked there, though, Meyers’s building represented a vast improvement; before, the hospital had housed its mentally ill in grim basement dorms where the beds were so close together that one could walk on them from one end of the long room to the other without ever touching the floor. Treatments were joltingly primitive; on the new building’s opening night, the old facility’s patients were given enemas containing tranquilizers, then, when they were soiled but unconscious, whisked a couple of blocks north to their new home three at a time.

To the healthy and/or wealthy, Bellevue was still considered a hellhole. But that didn’t prevent it from becoming a pit stop for a roiling, turbulently unhappy segment of cultural and literary New York, a chapter in the biographies of countless writers and artists. A very young Eugene O’Neill was taken there after attempting suicide, and in 1935, Malcolm Lowry (Under the Volcano) spent two weeks being treated for acute alcoholism. In 1946, the story goes, Joan Vollmer, the wife of William Burroughs, was found on the street, incoherent and neglecting her infant daughter. She was committed for psychosis brought on by the amphetamines she and Burroughs had been injecting. Vollmer may or may not have been psychotic, but Burroughs was certain he didn’t want her in Bellevue. Seven years earlier, he had gone to his analyst’s office and presented him with the tip of his own finger, which he had severed in order to impress a young man. The analyst had called Bellevue. Burroughs knew what was on the other side of those gates, and he got Vollmer out.

The Lost Weekend crystallized the idea of Bellevue as a snake pit in the public mind; it scarcely mattered that what moviegoers were seeing onscreen was, to some degree, the result of reforms. The open, privacy-free wards had been created after a major scandal in which three nurses were accused of strangling an alcoholic patient to death; their actions were unseen because of the partitions that separated one bed from another.

But such improvements did little to change the fact that in the popular consciousness, Bellevue had become “Bellevue”—the last resort, the fatal prognosis, the finish line. In reality, it wasn’t: For those in the alcoholic ward, the hospital was a place to return over and over. And for those committed to the psychiatric ward, it might be the first stop on the way to prison, or to a state institution for the criminally insane, or to a private sanatorium if they had the requisite means.

The lucky ones went home, with war stories, battle scars, fodder for their art. In his larger- and possibly more-interesting-than-life autobiography Beneath the Underdog, Charles Mingus, known as “The Angry Man of Jazz,” wrote of his time at Bellevue in the late fifties, claiming to have encountered the young Bobby Fischer in one of the dayrooms, “very tall and gangly, sandy haired, only about 18 years old … He checkmated me three times.” It’s not clear if Fischer (whom Mingus never calls by name) was actually there, though he certainly would have fit right in. But Mingus definitely was and commemorated it in music. As his instrumental “Lock ’Em Up (Hellview of Bellevue)” begins, the drums, piano, and horn runs take off at a frantic clip, sounding like something you might hear in the jazz club in Sweet Smell of Success. But as the piece continues, it takes on a nerve-jangling, argumentative quality. Musically, it seems to lose its train of thought. The instruments fall out of communication with one another. Then they all shout at once. Suddenly, the music stops. The piece is punctuated by what sounds like one man’s hoarse yelp of agony. And then it starts again, and fades away, in a distracted tangle of horns making sounds like approaching sirens and human cries.

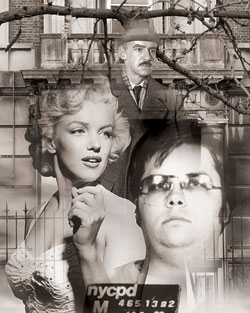

At times, it’s been hard to tell where fact ends and mythmaking begins. In her biographical novel Blonde, Joyce Carol Oates places Marilyn Monroe in Bellevue, “streaming blood from two slashed arms, carried inside on a stretcher stark naked and raving. This had been in Winchell’s column.” It sounds true, although in reality, Monroe was treated for depression in 1961 at the much more upscale Columbia Presbyterian.

For the Beat Generation, the hospital was a virtual clubhouse. Allen Ginsberg was committed briefly in 1949, when he pleaded insanity after a police chase (he had been letting the junkie Herbert Huncke store stolen goods in his apartment). While inside, he met another patient/inmate, Carl Solomon, to whom he dedicated “Howl” in 1956. The hospital makes a cameo in the poem, as “the best minds of my generation … talked continuously seventy hours from park to pad to bar to Bellevue to museum to the Brooklyn Bridge.”

The line seems a lucid reflection of a moment in which Bellevue always seemed to be part of the conversation, the rough end to so many wild nights. Norman Mailer landed there in 1960, after he stabbed his wife Adele Morales. The Mailers had thrown a big party in their Upper West Side apartment, and at 3:30 a.m., after the guests (among them Ginsberg) had gone home, Mailer approached Adele, who was getting ready for bed. She later told detectives he had “a funny look in his eye. He didn’t say a word. He just looked at me. Then he stabbed me.” Twice, with a penknife, in the abdomen and back.

Remarkably, Mailer then trotted off to do an interview with Mike Wallace in which he reiterated his intention to run for mayor, posited that juvenile delinquency could be reduced by staging medieval jousts on horseback in Central Park, and brushed aside Wallace’s inquiry about the cut on his face with a grin. When police picked him up, he was taken to Bellevue, after having been pronounced “both homicidal and suicidal.” “Your recent history indicates that you cannot distinguish fiction from reality,” said the judge, who was not, apparently, referring to the author’s gift for rethinking literary genres.

“It is very important to me not to be sent to some mental institution,” Mailer replied. “I’m a sane man. If this happens, for the rest of my life, my work will be considered as the work of a man with a disordered mind.”

Mailer and his reputation survived Bellevue (Adele didn’t press charges, although their marriage was soon over). But for many others, Bellevue was, if not the end, the beginning of the end. The hospital was a way station and a harbinger of misery for Edie Sedgwick and Charlie Parker. Delmore Schwartz, then the poetry editor of The New Republic, was committed in 1957 after attacking the critic Hilton Kramer, whom he imagined was having an affair with his estranged wife. Schwartz got out but returned more than once in the downward spiral of addiction and mental illness that defined the decade before his death. In 1975, Saul Bellow memorialized him as Von Humboldt Fleisher in the novel Humboldt’s Gift: “To me, Bellevue was like the Bowery,” Bellow wrote. “It gave negative testimony. Brutal Wall Street stood for power, and the Bowery, so near it, was the accusing symbol of weakness. And so with Bellevue, where the poor and busted went … And poets like drunkards and misfits or psychopaths, like the wretched, poor or rich, sank into weakness—was that it?

“From Bellevue he phoned me … He yelled, ‘Charlie, you know where I am, don’t you? … This isn’t literature. This is life.’ ”

The idea of being alone in a padded cell has less psychic heft now. “Nervous breakdown” is antique.

Every generation has seen its bleakest self-image reflected in stories of the hospital; the notion of Bellevue that New Yorkers share has always been, and remains, a focal point for what we understand, and what we don’t want to understand, about the seriously mentally ill. A century ago, it was a place that misapprehended senile dementia as a kind of insanity. The Prohibition years bred a catastrophic rise in what was then called “dipsomania.” Before 12-step programs, there were just two steps for Manhattan’s indigent alcoholics: Go to Bellevue, and ride out the d.t.’s. In the fifties, the widespread use of tranquilizers and amphetamines created a new set of problems. And in the sixties, the news that Bellevue’s patients were suffering horrifying abuses made the hospital the center of a public outcry.

Some serious reforms followed, part of a nationwide movement intended to protect the civil rights of the mentally ill. By the seventies, the hospital had not only its own in-house courtroom for competency hearings but also a staff of lawyers who were paid to advocate for the patients and often argued in favor of their release. Bellevue remained perpetually undermanned and underfinanced, an emblem, for years, of urban government’s catastrophic inattention to its own public institutions. And yet, even at the roughest times, the hospital engendered a fierce and embattled loyalty among those who worked there. “I don’t know if it was a kind of masochism or a kind of macho—and that applies to the women as well—a sense of pride in being able to do the most difficult jobs in the most difficult place and do them well,” says Frederick Covan.

Bellevue, he says, was “always a zoo. Never enough rooms, never enough space for people to be waiting—and the people who were waiting were not exactly calmly sitting around until they could be interviewed.” When patients came up the 29th Street ramp to the first-floor admitting area, “the majority were probably brought in by the police, since severely mentally ill people don’t have the insight to know they’re severely mentally ill. So usually you’d have cops all over the place in the psych ER.” Adding, literally, to the boiling-point atmosphere was the fact that the hospital had very spotty air-conditioning—a particular problem since summer heat waves exponentially increased the kind of behavior that tended to land patients in Bellevue in the first place.

The criminal mentally ill would be taken upstairs quickly, to a second-floor prison ward administered by the Department of Corrections. In Bellevue’s unnervingly small and unreliable elevators, that one-floor journey could make for an interesting ride—two or three cops, a couple of very angry shackled arrestees, and a staff psychologist or psychiatrist politely pressing his back against the far wall and hoping that the doors would open soon. The rest of the patients would wait downstairs for their evaluations in the ER, and those in the most serious trouble would be, as the jargon had it, “two-PCed”—meaning that two physicians would have to sign certifications mandating a 72-hour hold.

The infamy of the old Bellevue reached its apotheosis in December 1980, when the police brought in Mark David Chapman, the man who had just killed John Lennon. Chapman was wearing a bulletproof vest and surrounded by armed officers in flak jackets, who themselves were frightened that someone would penetrate the scrum of reporters and photographers to try a Jack Ruby–style attack.

For a few weeks, according to one senior staffer, Chapman was shuttled between Rikers Island and Bellevue, which wanted him there as little as possible. Police snipers manned the roof of the hospital. Covan found himself on the team in charge of evaluating Chapman’s competency.

“What’s it like being here?” he asked Chapman, who had been put on suicide watch in the prison ward.

“What do you think?” the 25-year-old killer replied, starting to laugh and squirm, alternately giggling and apologizing.

“That was a challenge,” says Covan. “I’ll tell you, we did not like him very much. Most of us were of the generation that loved Lennon. But when you met Chapman, he was so pathetic that it was hard to maintain a sense of anger at him—because he was just not able to withstand the anger that you felt. It wasn’t that I felt sorry for him, it was just … how can you be angry? Just be angry at the situation: Lennon’s dead, and a sick man did it.”

By the time old Bellevue closed in the mid-eighties, the landscape of public-health policy for the mentally ill had changed remarkably. After 54 years, the facility looked and felt outmoded. There were treatment rooms still filled with bathtubs covered with canvas sheets that left just enough room for a patient’s head to stick out; the huge basins, which were once thought to calm the manic, had lain unused for decades, museum relics of a less enlightened time. An improvement in the quality and variety of drugs had transformed patient care. And the widespread deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill in the sixties and seventies made the prospect of extended incarceration in a state-run sanatorium much rarer. When once a patient could have spent months wandering between the wards and the dayrooms on the upper floors, by the mid-eighties the average length of a stay was, says Covan, “maybe twelve days. Longer than that, and you had the administrators on your ass trying to get you to get rid of them unless they had good insurance, and even the insurance companies were pushing to get ’em out, get ’em out, get ’em out.”

Over the last couple of decades, Bellevue’s status as the endpoint of an urban nightmare has played a dwindling role in the city’s collective unconscious. The idea of being alone and unattended in a cell, hopelessly insane, lost to the world forever, seems to have less psychic heft in an age when so few people, for any reason, actually do go away and stay away. For younger New Yorkers who were reared on the notion that excessive behavior is, at worst, followed by brief time-outs, “nervous breakdown” is an antique phrase from the Mad Men era, and the spooky concept of a permanent one-way trip to a padded room has been supplanted by a 28-day haul in rehab, an in-and-out scenario much more within imaginative reach. If Bellevue becomes a five-star destination for those who want to escape the cares of the world, sleep all day, and have their rough edges sanded away so they can return to the world refreshed, perhaps its metamorphosis from hell to hotel will just seem like the next step in patient care.

As for the actual rather than the figurative Bellevue, it’s now a more modern hospital, in a different building, in a new era. It seems unlikely that anybody would be sorry to see the words “Psychiatric Hospital” chipped off the northern entrance of its old quarters. And while the EDC’s plan to turn Bellevue into the latest in luxe accommodations has occasioned a certain number of jokes about the Sid Vicious Suite (yes, he’s an alum) and the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Casualty Atrium, those memories aren’t likely to have much traction. After all, nobody is more expert at eradicating swaths of urban history with great dispatch and little sentimentality than a real-estate developer.

We’ll see if the ghosts cooperate. Perhaps to appease them, the future Hotel Bellevue could nod to its storied past. Maybe in an unobtrusive corner—or, more appropriately, over the bar—someone could mount a plaque with these words from Malcolm Lowry, who spent decades trying to make sense of his time inside.

“My God, he thought suddenly, why am I here, in this doleful place?” Lowry wrote. “And without quite knowing how this had come about, he felt that he had voyaged downward to the foul core of his world … But here too, equally, he thought, looking at the doctor, was perhaps the cure.”