To reach the home of George Obama, the president’s youngest half-brother, you skirt around the skyscrapers of central Nairobi and head north twenty minutes toward Huruma, one link in a necklace of slums that encircles the Kenyan capital. Turning off a half-built highway, you plunge into a warren of honking cars, minibus taxis, stray cows, and open roadside sewers. In the afternoon, Huruma’s alleys flood with children in neat school uniforms who skip past clapboard kiosks selling cigarettes, sodas, eggs, and detergent. You stop at a soccer field, an uneven red-dust pitch with netless goals, and ask one of the young men who are standing around in knots whether they’ve seen George. Everybody knows him: He used to be a quite a soccer player. You get directions to his house, a single-story tin-and-cinderblock structure, and finding it empty, manage to cadge his cell-phone number from a neighbor. You call George and then you wait.

Eventually, he appears with an entourage of young men, who fan across the gravel alley, like a street gang readying for a rumble. George is the tallest and the skinniest and clearly the leader, striking a 27-year-old’s cocksure pose, his elbows jutting, his long slender fingers delicately holding a cigarette. In his height, slim build, and long, expressive face, you can catch a glimpse of his half-brother, Barack. But the resemblance is obscured by evidence of a harder life: George’s eyes are misty, narrowed into slits by heavy lids, and his arms are flecked with scars. The product of a relationship between Barack Hussein Obama Sr. and a Kenyan woman named Jael Otieno, George never knew his father, who died when he was 6 months old. You hold up a hand in greeting as you walk across swirled scraps of paper and discarded plastic, and explain why you’d like to talk. A barefoot child scurries over to hand George another couple of smokes, bought individually for a few shillings from a nearby kiosk. As he clamps one between his lips and lights up, George shivers despite the midday warmth.

Little but a name and a few strands of DNA link this man to the current occupant of the White House. Yet over the course of the last year, George Obama has found his life transformed by the fearful power of associative celebrity. In August 2008, around the time his half-sibling Barack was accepting the Democratic nomination, Italian Vanity Fair reported that it had tracked down George to Huruma, dragging him into the vortex of a faraway political freak show. (Drudge’s headline: “Obama’s ‘lost’ brother found living in Kenya—in a hut!”) Since then, he’s been pestered by tabloids, subjected to embarrassment—a minor marijuana arrest made international news—and has unwillingly auditioned for the role of Billy Carter in this latest, and most unprecedented, version of America’s First Family. But along with the glare of exposure has come the glint of opportunity.

Early next year, George is scheduled to publish a memoir, Homeland: An Extraordinary Story of Hope and Survival, and embark on a U.S. publicity tour. “The story would have interest whether the guy was related to the Obamas or not,” says David Rosenthal, the publisher of Simon & Schuster. “It’s somebody who was born in relative privilege in Africa, who becomes a little bit of a bad seed, and ends up working as an activist.” But surely Rosenthal would not have paid a reported six-figure advance had George’s story come with a different last name.

Despite the book deal, there’s little outward evidence of change in George’s modest existence. He carries an expensive touchscreen phone, but he still lives in his same house in the slums. George is co-writing the book with Damien Lewis, a self-described “author, war reporter, and adventurer” with some experience in this line of work (in 2005, Lewis co-authored a memoir called Slave with a Sudanese woman named Mende Nazer, who had been sold into bondage). Rosenthal says that he doesn’t know how the two men are dividing the advance, and neither Lewis nor the book’s agent would comment.

When he’s asked, last month, to talk about his memoir, George nods slowly, a smile flickering at the corners of his mouth. “I’ll give you an interview,” he says with a slow drawl. “But you have to give me 500 pounds.” He then cocks his head toward the tough-looking fellows standing behind him. “What about my bodyguards? You have to pay them, for their time.”

He eventually accepts, in lieu of payment, a series of invitations to lunch. For the meetings, he picks one of the most expensive restaurants in town, the Safari Park Hotel, where a giant elephant statue dominates a lobby styled after a supersize village hut. George is good company: He talks about sports, boasting that the youth soccer team he coaches is doing well in the local league, and politics, complaining about Kenya’s notoriously corrupt elites. He says that no matter how well his book sells, he plans to stay in Huruma—it is home. But when the conversation verges onto anything personal, he refuses to budge from his monetary demands. “What do I get?” he demands to know. To the suggestion that he might want publicity for his forthcoming autobiography, he shakes his head and mutters, “They’ll have to pay me.”

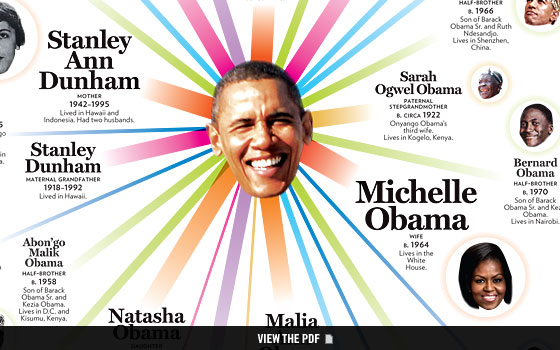

You can hardly blame George—a street-smart guy in one of the poorest corners of the world—for trying to capitalize on America’s fascination with the unusual lineage of its latest president. In Dreams From My Father, Barack Obama wrote of a journey of self-discovery that ultimately took him to his Kenyan roots. Almost all of his living relatives run through his father, Barack Obama Sr., whom he remembers meeting only once in Hawaii at the age of 10. Obama Sr. was born to Hussein Onyango Obama, who worked as a domestic for British employers and served in the Second World War as a cook for a British captain. Onyango came home with a photograph of a white woman (whose name has been lost to history) he claimed to have married in Burma. Onyango had three wives in Kenya: Helima, Akumu, and Sarah, the only one known to be still living.

By all accounts, Onyango was a mean-spirited man. He clashed violently with Akumu, the mother of Obama Sr. Family lore says that Akumu ran away after the birth of her third child. Little is known of the whereabouts of Obama Sr.’s sisters, Auma and Sarah.

Obama Sr., was part of the Kenyan generation that came of age with uhuru, or independence, and was a beneficiary of a scholarship program that brought him to the States. After a short marriage to Stanley Ann Dunham, the president’s mother, he earned a master’s from Harvard, returned to Kenya, and became a government economist. He had overlapping relationships with at least four different women, in keeping with accepted East African cultural practice. When the younger Barack Obama first visited Kenya in 1988, he learned that his father had experienced a series of personal and political misfortunes later in life, and had died a broken man at the age of 46. He left behind a large set of heirs, and competing factions of the family fought over his meager estate.

Dunham died in 1995 of ovarian and uterine cancer at the age of 52. She was 18 when she married Obama Sr. A few years after their divorce in 1964, Dunham met and married Lolo Soetoro, an Indonesian student who later became a geologist and oil executive. The family moved to Indonesia, where Ann would live, on and off, for the rest of her life. She studied for a Ph.D. in anthropology, and after fourteen years of research produced a 1,043-page dissertation on peasant blacksmithing in Indonesia. In December, a revised version will be republished by Duke University Press. A feature-length documentary about her life will begin shooting next year.

Neither of Barack Obama’s parents, of course, lived to see their son become president. But now that he has, the background players in his family drama—half-brothers, step-grandmothers—are experiencing a disorienting measure of reflective fame. They’re doing their best to handle it, with varying degrees of grace.

The Confidante

Maya Soetoro-Ng, the child Ann Dunham had with Lolo Soetoro, is writing a children’s book premised on explaining her mother’s peripatetic life to her own 5-year-old daughter, Suhaila. Soetoro-Ng is the only sibling that Barack Obama knew growing up, and the two are close. She has played an honorary role in his administration, serving on the President’s Commission on White House Fellowships. Formerly a high-school teacher in Hawaii, she left her job this spring and is now spending part of the year in Washington, where her husband, a professor named Konrad Ng, has a fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution.

The Matriarch

Everyone remembers Obama’s tearful final visit with his maternal grandmother, who died two days before the 2008 election. But he still had another “granny,” as he calls her, back in Kenya: Mama Sarah, his octogenarian step-grandmother (Onyango’s third wife). Within hours of Obama’s victory, electricity lines were planted on the Obama-family homestead in the village of Kogelo, in western Kenya. In the African countryside, where advancement is measured by the replacement of a thatch roof with metal, this counted as a major sign, as if any were needed, that the Obamas were moving up in the world. In the afternoon, you can still see Mama Sarah, the mistress of the house, sitting under a mango tree behind a chain-link fence guarded by police. But neighbors say that the family has become somewhat reclusive of late, and Mama Sarah is no longer a regular fixture at the playground with baskets of mandazis, deep-fried dough balls, for the local children. However, for tourists who are willing to pay $500, there’s a possible answer: a round-trip package from Nairobi called the “Obamaland Weekend Break,” which features a tour of the local sights, and a potential visit with Mama Sarah.

The Spokesman

Sayid Obama, one of Onyango and Sarah’s four children, lives in the lakeside town of Kisumu, six-hours west of Nairobi, and has at times acted as the unofficial spokesman for the family members living in Kenya. It’s a tough job: He’s constantly fielding calls from the media. The British press has dominated the coverage of the family, in part because of the country’s colonial ties to Kenya, in part because British papers have fewer compunctions than American ones about paying for interviews. Sayid is sick of dealing with it. “We have been grossly misquoted by the press,” he says over the phone in his native Luo. “We are aware of people posing as tourists and journalists coming to Kogelo asking questions that sometimes place the legitimacy of Barack’s presidency in question. There are those from the ‘birther’ movement who want to undermine him all the time. Pressure is piling on us to behave in a certain manner that is a bit impossible. We’ve always been this quiet family, and we intend to remain that way.”

The Pitchwoman

Barack Obama Sr.’s first wife, Kezia, now lives in the London suburb of Bracknell. During the 2008 campaign, she became a minor celebrity in the Fleet Street tabloids, which descended on her house to describe her modest life, her enthusiasm for playing bingo, and her glowing opinions of her stepson. (“He was so much like his father,” she told the Daily Mail, “his looks, his voice, everything.”) After the election, Kezia formed a relationship with the Gala Coral Group, a large British gambling company, becoming the celebrity face of an online game called “Mrs. Obama’s Bingo.” (Ten percent of the proceeds benefit a palliative-care charity.) The launch of the game coincided with Barack Obama’s inauguration. Kezia, who attended, was chauffeured to the airport in a bright-yellow taxi covered with “Gala Bingo” branding. When she returned home, she made a series of appearances on the company’s behalf. “She was pretty uncomfortable talking to anyone, and she was desperately afraid of offending Barack, putting her foot in it, or saying the wrong thing,” says Patrick Barkham, a columnist for the Guardian, who interviewed her between calls at a bingo hall. She told Barkham that she’d enjoyed seeing her stepson at the inauguration, but added that he’d warned the family that reporters “sometimes turn the truth upside-down.”

The Philanthropist

Kezia’s oldest child, Abon’go Malik Obama, was a bit of a hell-raiser in his younger days, but he has since converted to Islam, sworn off drinking, and devoted himself to the cause of fighting poverty. Malik now splits his time between Washington, D.C., where he used to work for an international-development consulting firm, and Kisumu, where he owns an electronics shop. He recently started a nonprofit organization in memory of his father. According to its website, the Barack H. Obama Foundation will focus on literacy, health, and sanitation projects in the communities surrounding Kogelo. A picture gallery shows various projects under construction, including a new well, a madrassa, and a house for the local imam (suggesting, if nothing else, that the White House wasn’t involved in awarding the grants). Malik Obama has not sought publicity for his foundation. “We need some peace now,” he says, referring to the media attention the family has received this year. Prospective board members say the foundation is still in its infancy and will be formally launched at a later date. It is, however, already accepting tax-deductible donations via PayPal.

The Watchdog

Kezia’s daughter Auma Obama is probably the Kenyan relative the president knows best: She acted as Barack’s guide when he made the pilgrimage he describes in Dreams From My Father and was later a bridesmaid at his wedding. She’s a vigilant guard of the family’s name and privacy, although her powers of message control have their limits. Last May, Auma’s ex-husband, Ian Manners, who lives in Britain, announced that he intended to seek a seat in Parliament as a Conservative Party candidate, telling the London Evening Standard that, despite their ideological differences, he planned to reproduce some of “the magic that Barack Obama has sprinkled over the White House.” Auma, who divorced Manners almost a decade ago and now lives in Nairobi, promptly rebuked her ex for “riding on my brother’s name.”

The Playboy

Kezia’s third child, Abo Obama, runs a cell-phone shop on the outskirts of Nairobi. In April, the tabloid News of the World reported that during a layover in London on his way to the inauguration, Abo (who goes by the name Samson) was denied entry into Britain on the grounds that he’d been accused of an attempted sexual assault. The incident, which had allegedly taken place the previous November, involved his following a group of girls—one 13 years old—into a café not far from his mother’s home. Through his ex-brother-in-law Ian Manners, Samson said the allegations were “absolute lies.” “He is a bit of a playboy,” Manners told the Times of London, “but would not get involved with 13-year-old girls. It is unthinkable.”

The Quiet One

Bernard Obama, Kezia’s youngest son, reportedly runs an auto-parts firm in Nairobi. The Sun caught up with him last year. He revealed little beyond the fact that he is a fan of the soccer club Manchester United.

The Pianist

Last month, Mark Ndesandjo, the president’s half-brother, released a self-published autobiographical novel entitled Nairobi to Shenzhen. Barack Obama has written that meeting Ndesandjo was “like looking into a foggy mirror,” and indeed, the two Ivy League–educated half-brothers have some superficial similarities. But as Nairobi to Shenzhen makes clear, they have very different feelings about their families. Whereas the younger Obama portrays his father as a distant, imperious, but talented man, Ndesandjo, who lived with him throughout his childhood, describes him as a monster and their relationship as “cataclysmic, debilitating, histrionic, humiliating, and overbearing.” In a press conference two weeks ago, Ndesandjo recalled that his father used to beat him and his American mother, Ruth. Those picking up Nairobi to Shenzhen for the unauthorized family story, however, will come away disappointed: It is a 350-page love story about a Chinese woman named Spring, filled out with cultural observations and digressive philosophical musings. There’s no mention of his feelings about the president, though some may be forthcoming: Ndesandjo says he’s has recently completed a memoir.

The Ex

Mark’s mother, Ruth Ndesandjo, who eventually divorced Barack Obama Sr. and married a Tanzanian, currently runs a school in Nairobi. In his memoir, Barack Obama was notably harsh in describing his first meeting with her, calling the encounter an “ordeal.” How Ndesandjo felt about the portrayal is unknown. In a 2008 interview with the Kenyan newspaper The Daily Nation, the only one with her on record, she refused to answer any personal questions.

The Defendant

If there is one person who has truly suffered from all the attention, it’s Barack Obama’s half-aunt, Zeituni Onyango. She first came to public notice when the Times of London began digging into the whereabouts of several of the more reclusive members of the Obama family. Through public-records searches and cold-calling, James Bone, a U.S.-based correspondent for the newspaper, was able to track her to Boston. After phoning her house three times—on each occasion the same voice answered, once claiming that Zeituni Onyango had died the previous summer—Bone traveled to Boston and staked out her address, a ground-floor apartment for the physically disabled in a public-housing complex. Eventually, Onyango, an elderly woman who walks with a cane, left her apartment to go shopping, and Bone approached her for an interview. Within days of the appearance of Bone’s story, the reason for Onyango’s reticence became clear: She was residing in the U.S. illegally, since a judge had denied her asylum appeal in 2004.

Since then, the president’s illegal-alien aunt has become a favorite target for the conservative fringe. (Glenn Beck has particular fun with ostentatious mispronunciations of her name.) Onyango herself has been driven more or less into hiding, emerging only for a brief August interview with a local television station and an immigration-court date in Boston, for which she disguised herself from photographers by wearing sunglasses and a curly red wig. At a hearing next February, she will likely learn whether she’ll be deported. In her TV interview, she said she wasn’t hoping for any special treatment from her nephew. “I don’t want to disturb him, because he’s got a big job to do.”

The Missing Obamas

“Missing” Obamas have been an ongoing target of the international press. It’s impossible to confirm how many are at large, and given the size of most African families, it’s hardly surprising that new ones keep turning up. Nothing is known of the president’s blood-relation aunts Auma and Sarah. Jael Otieno, Barack Obama Sr.’s fourth wife, is believed to be living quietly in Atlanta. Sayid and Zeituni have two brothers: Yusuf, who lives in Kisumu and has yet to speak to the press, and Omar, who moved to the United States sometime in the sixties. James Bone tracked him to Boston, where the trail went cold. Bone believes Omar has gone underground, but the reporter holds out hope that he’ll find him someday.

Additional reporting by Robert Oluoch.