Skylar Shafran, a turquoise headband on her brunette head and a pink princess shirt on her string-bean frame, is standing on a chair in her living room, shifting from left foot to right. She has already gulped down a glass of orange juice and nibbled on some crackers; she has also demonstrated, with extemporaneous grace, the ability to pick up Hello Kitty markers with her toes. For more than an hour, she has been answering questions to a mock version of an intelligence test commonly known to New York parents as the ERB. Almost every prestigious private elementary school in the city requires that prospective kindergartners take it. Skylar’s parents, Liz and Jay, are pretty sure they know where they’re sending their daughter to school next year, but they figure it can’t hurt to get a sense of where she sits in the long spectrum of precocious New York children. And so, although it wasn’t cheap—$350—they’ve hired someone to find out. Skylar has thus far borne this process with cheerful patience and determination. But every 4-year-old has her limits.

“What is an umbrella?” asks the evaluator, a psychology graduate student in her mid-twenties.

“To keep me dry.”

“And what is a book?”

“Something you read.”

“What is a house?”

Skylar squirms, teeters a bit.

“A house?” the tester repeats.

Skylar looks at her mother. “I have to go pee.”

Later, when the evaluation is over, Liz confesses she’s ambivalent about inviting a stranger into her home to assess her 4-year-old and even more ambivalent about the idea of prepping her for a standardized test, should it turn out she needs preparation. “It’s just that I want choices for her,” she says. “It’s an immigrant mentality. You want what’s best for your kid.”

The beauty of a meritocracy is that it is not, at least in theory, a closed system. With the right amount of pluck and hard work, a person should be able to become whoever he or she is supposed to be. Only in an aristocracy is a child’s fate determined before it is born.

Yet in New York, it turns out that an awful lot is still determined by a child’s 5th birthday. Nearly every selective elementary school in the city, whether it’s public or private, requires standardized exams for kindergarten admission, some giving them so much weight they won’t even consider applicants who score below the top 3 percent. If a child scores below this threshold, it hardly spells doom. But if a child manages to vault over it, and in turn gets into one of these selective schools, it can set him or her on a successful glide path for life.

Consider, for instance, Hunter College Elementary School, perhaps the most competitive publicly funded school in the city. (This year, there were 36 applicants for each slot.) Four-year-olds won’t even be considered for admission unless their scores begin in the upper range of the 98th percentile of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, which costs $275 to take. But if they’re accepted and successfully complete third grade (few don’t), they’ll be offered admission to Hunter College High School. And since 2002, at least 25 percent of Hunter’s graduating classes have been admitted to Ivy League schools. (In 2006 and 2007, that number climbed as high as 40.) Or take, as another example, Trinity School. In 2008, 36 percent of its graduates went to Ivy League schools. More than a third of those classes started there in kindergarten. Thirty percent of Dalton’s graduates went to Ivies between 2005 and 2009, as did 39 percent of Collegiate’s, and 34 percent of Horace Mann’s. Many of these lucky graduates wouldn’t have been able to go to these Ivy League feeders to begin with, if they hadn’t aced an exam just before kindergarten. And of course these advantages reverberate into the world beyond.

Given the stakes, it’s hardly a surprise that New Yorkers with means and aspirations for their children would go to great lengths to help them. Rather, what’s surprising is that a single test, taken at the age of 4, can have so much power in deciding a child’s fate in the first place. The fact is, 4 is far too young an age to reach any conclusions about the prospects of a child’s mind. Even administrators who use these exams—indeed, especially the administrators who use these exams—say they’re practically worthless as predictors of future intelligence. “At information meetings,” says Steve Nelson, head of the famously progressive Calhoun School, “I’ll often ask a room full of parents when their children started to walk.” Invariably, their replies form a perfect bell curve: a few at 9 and 10 months, most at 12 or 13, a few as late as 15 to 18. “And then I’ll ask: ‘What would you think if you were walking down the street, and you saw a parent yanking a 1-year-old child up from the sidewalk, screaming, ‘Walk, damn it?’ ” The same, he says, is true of a system that insists a child perform well on a test at 4 years of age. “Early good testers don’t make better students,” he tells me, “any more than early walkers make better runners.”

Let’s start with the most basic problem: School starts in kindergarten. No matter how a child is doing at that moment, no matter where that child is in the great swoop of his or her developmental arc, that’s when parents send their kids off to school. Given this very concrete constraint, standardized tests seem as fair a means as any to find gifted 4-year-olds—if not the fairest, considering the city’s tremendous cultural and socioeconomic diversity. That one test-taking experience may be the sole experience all kids share, and their scores the sole application datum that’s neither prejudicial (like a family’s net worth) or subjective (like recommendations from nursery schools). Unfortunately, not all city schools use the same tests, which means that first-time parents, already overwhelmed by the usual formalities of school enrollment, are forced to cut through a smog of acronyms. New York City public schools use the Otis-Lennon School Ability Test, or OLSAT, to help determine which students are eligible for their gifted-and-talented programs. The private schools use a modified version of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, or WPPSI-III, pronounced “whipsy.” (Yet because the Educational Records Bureau administers it—for a cost of $495—it is still better known to some parents as the ERB.) Hunter, because it operates under the auspices of Hunter College rather than the Department of Education, uses the fifth edition of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, or SB-5, to narrow down its first round of applicants. How these tests differ is mainly a question of emphasis and style: The OLSAT looks much more like an actual school exam—it’s administered by a licensed teacher, answered in multiple-choice bubbles in a workbook, and a bit more biased in content toward school readiness, like following verbal directions—while the WPPSI and SB-5 are IQ tests, interpreted by psychologists and more biased toward abstract reasoning. But the truth is, all three are pretty similar, at least at this level. As W. Steven Barnett, co-director of Rutgers’ National Institute for Early Education Research, notes: “Odds are they’re all going to have kids do something with triangles.”

Those who are bullish on intelligence tests argue they’re “pure” gauges of a child’s mental agility—immune to shifts in circumstance, immutable over the course of a lifetime. Yet everything we know about this subject suggests that there are considerable fluctuations in children’s IQs. In 1989, the psychologist Lloyd Humphreys, a pioneer in the field of psychometrics, came out with an analysis based on a longitudinal twin study in Louisville, Kentucky, whose subjects were regularly IQ-tested between ages 4 and 15. By the end of those eleven years, the average change in their IQs was ten points. That’s a spread with significant educational consequences. A 4-year-old with an IQ of 85 would likely qualify for remedial education. But that same child would no longer require it if, later on, his IQ shoots up to 95. A 4-year-old with an IQ of 125 would fall below the 130 cutoff for the G&T programs in most cities. Yet if, at some point after that, she scores a 135, it will have been too late. She’ll already have missed the benefit of an enhanced curriculum.

These fluctuations aren’t as odd as they seem. IQ tests are graded on a bell curve, with the average always being 100. (Definitions vary, but essentially, people with IQs of 110 to 120 are considered smart; 120 to 130, very smart; 130 is the favorite cutoff for gifted programs; and 140 starts to earn people the label of genius.) If a child’s IQ goes down, it doesn’t mean he or she has stopped making intellectual progress. It simply means that this child has made slower progress than some of his or her peers; the child’s relative standing has gone down. As one might imagine, kids go through cognitive spurts, just as they go through growth spurts. One of the classic investigations into the stability of childhood IQ, a 1973 study by the University of Pittsburgh’s Robert McCall and UC–San Diego’s Mark Appelbaum and colleagues, looked at 80 children who’d taken IQ tests roughly once a year between the ages of 2½ and 18. It showed that children’s intellectual trajectories were marked by slow increases or decreases, with inflection points around the ages of 6, 10, and 14, during which scores more sharply turned up or down. And when were IQs the least stable? Before the age of 6. Yet in New York we track most kids based on test scores they got at 4. (And we may not even be the worst offenders: As Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman note in their new book, NurtureShock, there are cities with preschools that require IQ tests of 2-year-olds.) “How can you lock children into a specialized educational experience at so young an age?” asks McCall. “As soon as you start denying kids early, you penalize them almost progressively. Education and mental achievement builds on itself. It’s cumulative.”

Most researchers in the field of childhood development agree that the minds of nursery-school children are far too raw to be judged. Sally Shaywitz, author of Overcoming Dyslexia, is in the midst of a decades-long study that examines reading development in children. She says she couldn’t even use the reading data she’d collected from first-graders for some of the longitudinal analyses. “It simply wasn’t stable,” she says. I tell her that most New York City schools don’t share this view. “A young brain is a moving target,” she replies. “It should not be treated as if it were fixed.”

Complicating matters further, IQs are least stable at the highest end of the spectrum no matter what age they’re assessed. The explanation for this is simple: There’s more room to fall the higher you go, and hence a greater likelihood that the score will regress toward the mean. Chance figures more prominently into high scores—a good night’s sleep, comfort with the tester—and lucky guesses on tough questions are worth more points than answers to midrange questions. In 2006, David Lohman, a psychologist at the University of Iowa, co-authored a paper called “Gifted Today but Not Tomorrow?” in the Journal for the Education of the Gifted, demonstrating just how labile “giftedness” is. It notes that only 45 percent of the kids who scored 130 or above on the Stanford-Binet would do so on another, similar IQ test at the same point in time. Combine this with the instability of 4-year-old IQs, and it becomes pretty clear that judgments about giftedness should be an ongoing affair, rather than a fateful determination made at one arbitrary moment in time. I wrote to Lohman and asked what percentage of 4-year-olds who scored 130 or above would do so again as 17-year-olds. He answered with a careful regression analysis: about 25 percent.

The implications of this number are pretty startling. They mean that three quarters of the seniors in a gifted program would no longer test into that program if asked to retake an IQ test on graduation day. So I wrote Lohman back: Was he certain about this?

“Yes,” he replied. “Even people who consider themselves well versed in these matters are often surprised to discover how much movement/noise/instability there is even when correlations seem high.” He was careful to note, however, that this doesn’t mean IQ tests have no predictive value per se. After all, these tests are better—far better—at predicting which children will have a 130-plus IQ at 17 than any other procedure we’ve devised. To have some mechanism that can find, during childhood, a quarter of the adults who’ll test so well is, if you think about it, impressive. “The problem,” wrote Lohman, “is assigning kids to schools for the gifted on the basis of a test score at age 4 or 5 and assuming that their rank order among age mates will be constant over time.”

Appelbaum, McCall’s co-author, puts an even finer point on the stakes. “No university I know,” he says, “would think of using a 4-year-old’s data to decide who to admit.”

A January 5 thread from the parenting website DCurbanmom:

Can anyone offer advice on whether I should by [sic] Aristotle Circle? I’m in a time crunch. Thanks!

10:08

My sister-in-law bought Aristotle Circle workbook and showed it to me. As a child psychologist, the workbook is so close to the real thing, I think it is cheating. That said, my nephew aced the test …

11:01

It is so sad that we have to do this—but what to do? [dear child] is at a disadvantage if everyone else is prepping and we are not.

11:09

There was a time, not that long ago, when few parents attempted to prep their 4-year-olds for kindergarten-admission exams. But then a few more began to do it, and then a few more after that, and then suddenly, normal-seeming people with normal-seeming values began doing it, too, and an arms-race mentality kicked in. Responding to parents’ anxieties and fears, some of the fancier preschools began subtly prepping their students—giving them similar exercises to do with blocks, introducing them to the concept of analogies. Expensive test-prep kits suddenly began to appear on the market. And high-end education consultancies began to bloom, like Aristotle Circle. Founded in 2008 by an M.I.T. graduate and former Wall Street analyst named Suzanne Rheault, it provides tutors, advisers, and—most important—prep books for apprehensive and even merely conscientious parents.

“I can understand people getting offended by 4-year-olds getting tutoring for these exams,” says Rheault when we meet in her Soho conference room. “But I’m not the one making them take them.”

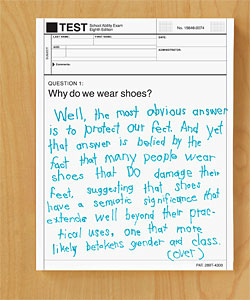

She dumps a bag of blocks onto the conference table. They’re essentially the same ones used on the WPPSI, except hers are white and blue rather than white and red. Then she plops down her meticulous, brightly designed prep book, which she just completed last August. She opens to the “Vocabulary” section, illustrated by a former cartoonist for Disney. “Any vocabulary the child needs,” she tells me, “is in this book,” whether it’s to complete picture analogies or understand questions that are asked of them. Then she flips to a section of the types of questions the children will be asked aloud—What is a villain? What is a liquid?—and a few pages after that, she gets to what she believes is the “core intellectual meat” of the exam: “Concept groupings,” or pages of pictures organized by how the objects in them are linked. Containers: picnic baskets, suitcases, matchboxes. Things that open and close: zippers, eyes, locks. Measuring instruments: hourglasses, watches, thermometers. “Any of the abstract groupings the child needs to understand are also here,” she tells me.

How does Rheault know all this? I ask her, incredulously. Has she seen one? You have to be specially registered with the publisher to buy the WPPSI. Like most IQ tests, it is updated only periodically, which makes it coveted by parents—if you’ve seen one lately, you’ve likely seen the version your child will take.

“I’m not going to talk about it,” she replies. “But the people who helped us develop the workbook are psychologists who’ve seen them.”

But copies of this test are obviously floating around. Skylar’s mother, for instance, says she was offered a copy of the WPPSI by a fellow mom. Type a few key search words on Urbanbaby.com, and within 30 seconds you’ll find this post: Have WWPSI-III to sell. Excellent condition. Complete set. E-mail me if you are serious and discreet. No questions asked. Cost is $3,000. (An e-mail address follows.) This past fall, a parent admitted to a psychologist who administers SB-5 tests for Hunter that he’d purchased a copy of the exam right off the publisher’s website. “The type of tests we sell are primarily for special education, so it’s never been an issue for us in the past,” says Elizabeth Allen, the director of research and development of Pro-Ed Inc., which only recently acquired the rights to the Stanford-Binet. “When I heard, I was like, ‘You’re kidding me! Some parent paid a thousand dollars so they could get their kid into a gifted program? Wow.’ ” (The company has since fixed the problem; now only licensed professionals can buy them.)

There are some who insist that studying for these exams can’t possibly budge a child’s scores. “I don’t know how prepping could help on the OLSAT,” says Anna Commitante, head of the Gifted and Talented programs for the city’s Department of Education. But Rheault can’t believe there’s still any debate about the subject. “The psychologists we work with,” she says, “say that 50 to 60 percent of the material is learnable.” Yes, her point of view may be colored by her commercial interests—her WPPSI prep books go for $500, and she’s now completing a workbook for the OLSAT and will shortly start one for the SB-5. But she’s hardly alone in her beliefs. “When people say this stuff isn’t really coachable, I always scratch my head and say, ‘Yeah, except for the parts that are,’ ” says Jonathan Plucker, director of the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy at Indiana University. “I understand the nature/nurture debate. It’s a complicated relationship. But to say that families with greater means and more interest in education can’t influence test outcomes—I can’t understand that reasoning. It’s common sense.”

The practice of prepping can run families into the thousands of dollars, posing a clear disadvantage to those who can’t afford it. But the truth is, even without coaching, children coming from economically and culturally rich backgrounds do far better on these tests. And that’s a far more urgent reason to challenge the widespread reliance on them.

“An analogy people use a lot for this is planting corn,” says Barnett, from Rutgers. “If you want to know about the properties of different kinds of corn, you have to plant it in land that’s well fertilized and well irrigated. If you plant it in soil that’s dried up and rocky, you won’t know, because nothing will grow.” The same, he explains, goes for children. How can one possibly know anything about their minds if they’ve spent their first four years in unstimulating environments?

“People have the idea that with these tests you can cancel out socioeconomic background and get to some real thing in the kid,” agrees Nicholas Lemann, dean of the journalism school at Columbia and author of The Big Test, a history of the SAT. “That’s a chimera. If you’re a 4-year-old performing well on these tests, it’s either because you have fabulous genetic material or because you have cultural advantages. But either way, the point is: You’re doing better because of your parents.”

Rather than promoting a meritocracy, in other words, these tests instead retard one. They reflect the world as it’s already stratified—and then perpetuate that same stratification.

“Instead of giving IQ tests, you could just as easily look at Zip Codes and the education levels of the parents to determine who gets the better schooling—you get a very high correlation between IQ and socioeconomic status in the first seven or eight years of life,” says Samuel J. Meisels, assessment expert and president of Chicago’s Erikson Institute, the renowned graduate school in childhood development. “Giftedness is a real thing, no question. But giftedness can be extinguished, and it can be nurtured.” He mentions a New York Times education analysis from 2008, which noted that after the city streamlined its G&T program, requiring specific cutoff scores for the OLSAT, the percentage of white students had shot up from 33 to 48 percent, while the percentage of black and Hispanic enrollment had fallen. “Sometimes,” he says, “you look at a big city’s decisions to do this and wonder if it’s about nurturing giftedness or if it’s about keeping middle-class families in the city limits.”

Skylar is allowed her potty break. She returns and stands on top of her chair.

“Okay!” says her evaluator, smiling. “So … what is a house?”

“I already know. A home.”

She gives Skylar a playful look and tips her head. “And what’s a home?”

Skylar mirrors her tipped head. “A house!”

She laughs. “What’s a bird?”

Skylar picks up her Hello Kitty pen and bounces it on her tester’s arm. “Look, a hopping marker!”

Her tester smiles. “What’s a bird—”

Skylar races the pen up and down. “Vrooooooooom! Magic marker! Vroom vroom!”

Watching this exchange is a reminder of something any parent knows: Four-year-olds, no matter how smart and delightful they may be, have obvious limits as test takers. Many, especially boys, can’t sit still for the full duration of an exam; others can’t stay awake or concentrate for that long, choosing at some catastrophic point to crawl under their desks and give up. Nor is the context in which these tests are administered exactly relaxing for young children. Both IQ tests require that they sit alone in a room with a tester they probably haven’t seen before. In the case of the WPPSI, the tester often isn’t allowed to prompt the children to give more complete answers, even if it’s clear they’re capable of delivering them (and would score better if they did). In the case of the OLSAT, the testers can’t even repeat the questions.

“What is a pet?”

“An animal. I have pet goldfish.”

Her tester decides to play along this time. “Do they have names?”

“Zoe and Tangerine.”

Skylar plants her marker next to a rectangular-shaped sticker she’d gotten as a reward for a previous exercise and admires the shape she’s just made. “Look! A flag!”

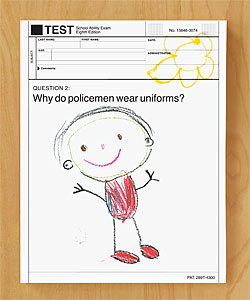

Stephen J. Bagnato, a professor of pediatrics and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, is fond of quoting Head Start co-founder Urie Bronfenbrenner, who in 1977 famously wrote, “Much of contemporary developmental psychology is the science of the strange behavior of children in strange situations with strange adults for the briefest possible periods of time.” It’s hard not to think about that observation in the context of intelligence-testing 4-year-olds. The script is so rigid, the tasks are so narrow and precise. Skylar did extremely well on her evaluation. Yet to me, the loveliest and most intellectually revealing moment was when she blew off all rules and made that whimsical little flag. If it were a real exam, the tester wouldn’t even have written it down. “Well, right,” says Bagnato. “When the examiner can only say certain things to these kids, and the child can only say certain things back, of course it’s too confining. We know that the way kids display their skills best is through creative play and everyday interactions at home and at school.”

As it turns out, intelligence tests miss lots of things, not just creativity. And perhaps that explains why IQs alone are not especially good predictors of excellence. In the twenties, for instance, Lewis Terman, a psychologist and deep believer in intelligence testing—it was he who revised Alfred Binet’s original test and came up with the Stanford-Binet model—started a now-famous longitudinal study of nearly 1,500 California children with extremely high IQs. He grandiosely called it “Genetic Studies of Genius,” and his hope was to show that these children, whom he called “exceptionally superior,” would one day form the backbone of the nation’s intellectual and creative elite, making crucial advances in sciences and public policy and the arts. But as David Shenk, author of the forthcoming The Genius in All of Us, points out, his subjects only grew less and less remarkable as time wore on. None won Nobel Prizes, though two who were specifically rejected for the study—William Shockley and Luis Alvarez—did, both in physics. None became world-renowned musicians, though two other rejects—Isaac Stern and Yehudi Menuhin—did, for their virtuosic violin-playing. In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell makes a similar point, noting that one’s IQ needn’t be super-high to succeed; it simply needs to be high enough. “Once someone has reached an IQ of somewhere around 120,” he writes, “having additional IQ points doesn’t seem to translate into any measurable real-world advantage.” In Genius Revisited, Rena Subotnik, director of the American Psychological Association’s Center for Gifted Education Policy, undertook a similar study, with colleagues, looking at Hunter elementary-school alumni all grown up. Their mean IQs were 157. “They were lovely people,” she says, “and they were generally happy, productive, and satisfied with their lives. But there really wasn’t any wow factor in terms of stellar achievement.”

So what do psychologists and educators think makes the difference between good and exceptional? Opportunity, connections, mentors. Perseverance and monomaniacal devotion, or what the psychologist Ellen Winner calls “the rage to master.” Creativity, a willingness to fail. Nelson, the head of Calhoun, can go on at urgent, passionate length about this.

“I want a school full of kids who daydream,” he says. “I want kids who are occasionally impulsive. I want kids who are fun to be with. I want kids who don’t want to answer the questions on those tests in the way the adult wants them to be answered, because that kid is already seeing the world differently. In fact,” he adds, after thinking it over for a moment, “I want kids who are cynical enough at age 4 to know that there’s really something wrong with someone asking them these things and think, ‘I’m going to screw with them in the process!’ ”

Granted, Calhoun is an unusual school, a place where kids don’t even get test scores until they’re freshmen. But one needn’t be particularly subversive to appreciate Nelson’s philosophy of educating 4-year-olds, or his frustration with current practice. “You have to play with blocks,” he says. “You have to make up stories. You have to muck around. Arithmetic and decoding language aren’t life—they’re symbolic representations of other things. And education is being diverted into focusing on these symbolic representations of the very experiences kids are being denied.”

Nelson says he’s considering scrapping the WPPSI as an admission requirement for Calhoun’s lower school, possibly starting as early as next year. As it is, he barely takes a kid’s score into account. One of the most compelling reasons to get rid of it, he notes, isn’t because the test is intellectually pointless. It’s because it’s emotionally insidious. “When we resort to any kind of measure of kids that’s supposed to be qualitative at a young age,” he says, “no matter how cheerfully we do it, no matter how many lollipops we hand out to de-stress the process, young children are extraordinarily discerning. They absorb their parents’ anxiety about it, they absorb the kinds of judgments people are making about them. So there’s a process of organizing kids in a hierarchy of worth, and it’s beginning at an age that’s criminal.”

The irony is that doing well on these exams can be just as damaging as doing poorly on them. “Gifted” is an awfully uncomfortable label for some children to wear. It can cripple their thinking, make them terrified of risk. “It’s not entirely inaccurate to observe that more and more high-achieving students go off to university and don’t care about anything,” says Nelson. “They don’t ask questions, they don’t have original ideas. And it’s not because there’s anything wrong with them, but because they were conditioned to believe that learning is about giving back the right answer.” Nelson knows it’s heresy to say this, but he wonders if it’s true. “These tests, at 4, start that long process of conditioning,” he says. “Right then, children start to believe that learning means pleasing the powerful adult in whose presence you are.”

It’s unlikely that most city schools will follow Nelson’s lead and stop testing 4-year-olds. But it is possible that these tests could earn less and less weight in the selection process as they become tainted by excessive prepping and anxiety. That doesn’t mean, however, that the selection process will become more democratic. “I’m afraid schools will be judging the child in ways that aren’t any better,” says Emily Glickman, founder of Abacus Guide Educational Consulting. “There’ll just be more weight on the school report, and what the nursery-school director says about the child verbally. And often kids who come from expensive, high-cachet nursery schools have elaborate evaluations written about them, because the preschool directors themselves have a high stake in the class’s placement success.” And in the case of private schools, she notes, even more emphasis may be given to a family’s socioeconomic status: “The kindergarten-admission process has always been about openly judging a 4-year-old and secretly judging the parents’ wealth, connections, and likeliness to give.”

Giving less weight to these tests doesn’t guarantee that the selection process would become more sensible, either, or more sensitive to finding those children who’d profit from an enriched education. After all, what mechanism should schools use?

This is the hardest question. Most education researchers can tell you just what’s wrong with intelligence-testing 4-year-olds. But few can tell you what should emerge in its stead. “Before we adopted the OLSAT,” says the Department of Education’s Commitante, “we had 32 different school districts using a huge … a tremendous variety of assessments.” Some, she says, relied on expensive IQ tests; others required teacher evaluations. The result was a hodgepodge of arbitrary standards—ones that, the city believed, worked against children who spoke English as a second language (the OLSAT is given in eight languages) or had lower incomes (the city gives the OLSAT for free).

Given his druthers, Meisels, at Erikson Institute, says he’d try to get a more comprehensive picture of the child. “And that can only be found through watching children in classroom situations,” he says. “And looking at the products of their work. And getting to know them. And that can be done through observational assessments.”

I try to interrupt him, but he anticipates my objection. “It’s not very practical, I know,” he says. “It means teaching teachers how to do it. It’d be more expensive. But you could do it. And then you’d get the right kids into these differentiated programs.”

Many researchers agree with him—and will add, as Meisels later does in our conversation, that kids ought never to be evaluated just once. “If one believes that kids do learn and improve,” says McCall, “then a few new kids should be eligible for gifted programs each year.”

If you’re looking for practical answers though, Plucker, of Indiana, has a modest proposal. He suggests that schools assess children at an age when IQs get more stable. And in fact, that’s just what City and Country, one of Manhattan’s more progressive schools, does. Standardized tests aren’t required of their applicants until they’re 7 or older. “That way, the kids are further along in their schooling,” explains Elise Clark, the school’s admissions director. “They’re used to an academic setting, they can handle a test-taking situation, and overall, we consider the results more reliable.” Even then, she says, her school still doesn’t weight IQ scores very much. “If we did, what we’d have is a group of kids with good test-taking skills and … I don’t know what else.”

But my money’s on the marshmallow test. It’s quite compelling and, apparently, quite famous—Shenk talks about it with great relish in The Genius in All of Us. In the sixties, a Stanford psychologist named Walter Mischel rounded up 653 young children and gave them a choice: They could eat one marshmallow at that very moment, or they could wait for an unspecified period of time and eat two. Most chose two, but in the end, only one third of the sample had the self-discipline to wait the fifteen or so minutes for them. Mischel then had the inspired idea to follow up on his young subjects, checking in with them as they were finishing high school. He discovered that the children who’d waited for that second marshmallow had scored, on average, 210 points higher on the SAT.

Two hundred and ten points. Can Princeton Review boast such a gain? Maybe our schools ought to be screening children for self-discipline and the ability to tolerate delayed gratification, rather than intelligence and academic achievement. It seems as good a predictor of future success as any. And Mischel’s test subjects, too, were just 4 years old.