On the night of February 21, 2009, a year before Army private Bradley E. Manning allegedly leaked the largest cache of classified information in American history, he sat at a computer in his barracks at Fort Drum in upstate New York. It was a Saturday in midwinter, and the barracks were nearly empty. He pulled a chair up to the computer in his cinder-block room, briefly debated between a pizza and a sandwich from Domino’s, went with the sandwich, and passed over into his “digital existence,” as he thought of it. He logged on to AOL’s instant-messenger service under the handle Bradass87, and off he went to transform himself. On the web, he could be whomever he chose.

It was 8:27 p.m. at Fort Drum when he popped up on the computer screen of ZJ Antolak.

“hi,” he began.

“hi,” ZJ responded.

“You don’t know me, i apologize, i got this [address] from your youtube channel.”

“No problem, there’s a reason I put it on there :P,” wrote ZJ, adding an emoticon to indicate her playful tone—or his, depending on your frame of reference. ZJ was Zachary Antolak, a 19-year-old gay activist and web designer. On YouTube, he went by the name Zinnia Jones. On the Internet, he was a she who called herself Queen of the Atheists, wearing her auburn hair below her shoulders and painting her lips a bold red.

Manning was an atheist himself—“I’m godless,” he told an acquaintance. But even more, he identified with ZJ’s self-invented life. “I saw your more personal stuff and figured you were on the same page … as me,” Manning wrote. “You remind me of … well … me.”

Among fellow soldiers, Manning had to conceal the basic facts of his sexual orientation. On the web, he was proudly out and joined a “Repeal Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” group. He’d even begun to explore switching his gender, chatting with a counselor about the steps a person takes to transition from male to female.

On the web, being one thing didn’t mean you couldn’t be another. And for all of his boundary-crossing and self-exploration online, he was, at first, a committed soldier. In fact, he was gung ho, eager to put his technical expertise to use for the cause—he had the skills of a hacker, though at that point, he didn’t yet have the ideology. The Army had trained him at Fort Huachuca as an intelligence analyst. “With my current position,” he wrote to ZJ with a new graduate’s earnestness, “i can apply what i learn to provide more information to my officers and commanders, and hopefully save lives … i feel a great responsibility and duty to people.”

Not that Manning’s conception of patriotic duty would have met with the approval of his superiors. His methods were hardly standard operating procedure. “In public eye, US intel services are mysterious; in the real world, intelligence is a goofy, clunky, and annoying process,” he wrote to ZJ. “drives me NUTS … luckily i use my DC contacts from Starbucks and get the word out to those higher up in the chain.”

ZJ played along with Manning’s espionage narrative. “I can imagine two guys in sunglasses meeting at a starbucks to quickly hand over an envelope … just to get some minor bug repaired,” she wrote, according to logs provided to New York Magazine.

Manning, though, had followed a different script. “Lol … glamorous, but no … it’s more like i knew this lt colonel from the DIA”—Defense Intelligence Agency—“at starbucks before i was in the military … slept with him once or twice, then i get in the military, i notice the problems, call him and say, hey, find someone who can fix this.”

In the gravityless world of the web, Manning could be all he wanted to be—gay, patriotic, and powerful, too. “I have long arms and a wide footprint,” he wrote from his deserted barracks.

When the computer was turned off and his Army comrades returned, his superpowers disappeared. The members of his platoon didn’t consider Manning a warrior, not like them. He’s five foot two and 105 pounds, as “tiny as a child,” one former soldier said. Military policy dictated that he hide his sexual orientation, but it probably wasn’t a secret to his platoon. “It took them a while, but they started figuring me out, making fun of me, mocking me, harassing me,” he wrote to ZJ, “heating up with one or two physical attacks.” Though, he assured ZJ, “I fended [it] off just fine.”

Over time, the pressures took a toll. At Fort Drum, Manning was losing control, lashing out at his tormentors. He had trouble with roommates, screamed at superior officers, his fists in balls. His master sergeant wasn’t sure he was mentally fit to deploy to Iraq, fearing he could do harm to himself or others. By August 2009, the month of Manning’s last chats with ZJ, he’d been referred to an Army mental-health counselor. Even online, his bravado slipped away. On August 7, 2009, almost six months after he first reached out to ZJ, he popped up on her screen. It was 11:30 p.m., a Friday night at Fort Drum. “i don’t mean to sound overdramatic, but im quite lonely,” he told her.

“Aww,” ZJ responded sympathetically.

“I’m okay,” he said bravely.

Two months later, Manning shipped out to Iraq with a top security clearance, his multiple identities held close inside him. There was abundant evidence that Manning was having trouble keeping it together psychologically, but the Army brushed aside doubts—it desperately needed intel analysts with Manning’s computer skills. After all, the Army was wired; in fact, the whole government had never been more networked, a development that had been pushed partly by the desire to improve information-sharing and shorten reaction time after 9/11. Much of the war was fought remotely; triggers were pulled by people in Langley, Virginia, or outside Las Vegas or field offices near Baghdad, where Manning was eventually posted. Military engagement had turned into a video game—but with real bullets. Manning was built for this sort of combat. In the modern Army, Manning’s skill set made him a highly useful soldier, and a dangerous one.

In Iraq, the torments Manning suffered at the hands of his fellow soldiers, his loneliness and concern over his gender, and the hours and hours he would spend in the airless intel office watching the brutal inner workings of the war bore down on him. He was unmoored in a way he hadn’t been before: angrier, less afraid, more certain of what was good and what was evil, and more compelled to act on this dawning righteousness. It was while in Iraq that Manning came across WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange—a charismatic authority figure who, far from rejecting him, as had so many others, took a passionate interest in him and what he had to contribute. Manning had an awakening—and he became, says the U.S. government, a traitor.

It was Bradley Manning’s father who pushed him to join the military. The afternoon I reached Brian Manning, he was at home in Oklahoma City, in a room in his ranch house that Bradley had briefly used as a bedroom. He’s out of work, his job at Hertz outsourced after 23 years. He’s in the midst of a second divorce, though on advice of counsel he’d refused to move out. Brian wanted to tell me about Bradley, though it was quickly clear his son was a mystery to him, and one he’d never been particularly interested in penetrating. Still, he wanted me to know that he’d tried to save his son, as a father would.

Physically, Bradley bears a certain resemblance to his father—both are “petit,” as Brian put it—but in other ways they couldn’t have been more different. Growing up, Brian was a “party animal.” He was raised in Chicago and left home when he was 17, commencing an epic sequence of benders that ended one Monday morning in 1974, when, on the heels of another drunken weekend, a 19-year-old Brian Manning found himself at a Navy recruiting office. The Navy trained him as an intel analyst, gave him secret clearance, and shipped him to Wales, where he married the first girl he met, a friendly, easygoing, semi-literate Welsh woman two years his senior.

After five years, Brian quit the service. He eventually took his wife and 6-year-old daughter to a dusty stretch of Oklahoma four miles from Crescent, a tiny conservative community with an Evangelical bent. He had five acres, pigs, chickens, and a big garden, and at first he and his wife enjoyed living like farmers. But then Brian’s priorities took another turn. He’d started a career in IT and was determined to climb a few rungs up the corporate ladder. By the early nineties, Brian was traveling frequently overseas for Hertz, leaving his family behind. “For me, it was a good career move,” he said.

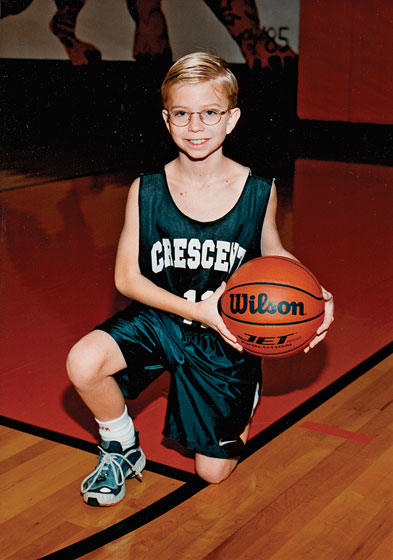

For Bradley, who was born in 1987, eleven years after his sister, his father sometimes seemed like a stranger. “One time, I came home after six weeks away and Bradley [then 3 or 4] didn’t recognize me,” Brian said. Bradley excelled at school, an A student and a math and science whiz who won the school’s science fair three years running. He did make a few friends among the smarter crowd, though in his father’s mind, Bradley was a loner who refused to make an effort, which perplexed his sociable father. “He’d get off the school bus, and he’d either go upstairs … or be downstairs on the computer,” he explained. “Basically, to put it in a nutshell, Bradley never showed any interest in anything outside [the house].” By the late nineties, Brian had essentially moved overseas for his job. “I’d call home every day and talk for a few minutes with my wife, but I don’t think I ever talked to Bradley, because usually he was busy on the computer doing something.”

Bradley’s mother tried to compensate for his absent father. She adored her son. “She wanted a boy so bad,” Brian said. “She doted on him terribly. You know, over here we’d say, ‘Spoil him rotten.’ ” But she could barely cope with day-to-day life, let alone a family’s needs. She didn’t drive and didn’t write well enough to make out a check. She soon slid into alcoholism, starting early in the day, and couldn’t always remember to give Bradley money for school trips.

Susan Manning divorced her husband in 2000, the year Bradley turned 13, and the next year, she took him to Wales, where she has a large family. (Bradley’s sister, then 24, stayed behind.) There, Bradley became the man of the house; on financial matters, his mother said, “Ask Bradley.” Bradley made some friends and showed some intellectual talent, even taking second place in a national math contest, as he boasted to ZJ. But he didn’t fit in. Students would be mean to him, abandoning him once on a camping trip, and teachers reminded him he was “a Yank.” “i hadn’t really assimilated,” he told ZJ. For Bradley, loneliness would always hover nearby; in Wales, it closed in on him. He imagined his sickly mother getting even sicker. Then he’d be completely alone. “at 17 y/o in desperation i called my father,” Bradley told ZJ.

His son’s call confused Brian, who’d all but written Bradley out of his life. They’d barely spoken in four years—except when the alimony check was late. Then his mother put Bradley on the phone to demand the money. And Brian had new loyalties. He was remarried, to a former co-worker, and his new wife had brought along her child, just a year younger than Bradley.

But Brian couldn’t turn Bradley down. “He’s my son,” Brian said, and that bond meant something to him. Perhaps there was a chance to make up for lost time. By then he’d moved to a ranch house in Oklahoma City—the homesteading experiment had ended, as had the European postings. In 2005, Bradley moved in, and for several months, everyone coexisted peacefully. Bradley landed a great job as a developer for Oklahoma City–based Zoto.com, which once hoped to compete with Flickr. The job earned him not only a paycheck but also his father’s respect. Brian said, “I took him for the interview, and …he comes out with the president, who told me, ‘Sir, you’ve got an extremely intelligent son here. I’m going to hire him on the spot.’ I felt really good about it.”

Bradley loved the job at first, and two years later, he boasted to ZJ, “they’re still using designs I developed.” He told ZJ he was let go after about four months over manpower issues, though the press reported his erratic behavior was a contributing factor—reportedly, at times he just stared into space.

With Bradley out of work, life at home deteriorated. He was sullen and depressed—the family doctor prescribed Lexapro. Soon his father’s long-simmering resentments surfaced. As Brian saw it, “Having … complete power over his mother, Bradley became very assertive. And he comes back over here and he finds out he’s no longer the head bull. He didn’t like that at all.” Bradley’s stepmother was busy with her own son, who also made demands on Brian’s attentions, which tormented Bradley. To her, Bradley was a freeloader, and his father backed her. “When he lost his job, he just felt like we should just take care of him,” said Brian. “That didn’t go across very well.” Bradley was by then living openly as a gay man. Brian accepted it, he said, but his wife thought he was faking, playing gay to get attention. Bradley responded by throwing it in her face. He sometimes applied eye makeup before going out to a gay club and even brought a boyfriend home to spend the night.

On March 29, 2006, tensions boiled over. His stepmother said something about him getting a job. In anger, Bradley grabbed a butcher’s knife and threatened her. His father, who was recovering from prostate surgery at the time, tried to get involved but slipped and fell. Bradley’s stepmother called the police. “Get away from him,” she can be heard yelling at Bradley on a 911 call, though in the background, Bradley seemed calm. “Are you okay, Dad?” he asked plaintively.

His stepmother wanted him out, and the police escorted Bradley from his father’s home. The next day, he was an 18-year-old on his own, driving the country in a vehicle his father had given him. “Lived in a pickup truck, sleeping in the ohare parking lot, commuting downtown during the day … LONG story,” he wrote to ZJ, who lives outside Chicago. He worked at a bunch of dead-end jobs: a pizza store, a guitar center, an Abercrombie & Fitch, and a Starbucks in the D.C. area, where he’d moved in with his father’s sister, Debra Manning. She wanted to help him along in the world. He was no bother. “He was not used to having anyone do anything for him,” said his aunt. “He didn’t ask for anything,” mostly keeping to himself, listening to music or surfing the web. Sometimes he’d break out of his shell, and then words came quickly. “He’s high-strung, talks fast, talks at people, and he’s impatient with people who don’t pick up quickly,” his aunt said with affection. And he was a know-it-all. She laughed, adding, “He knows what’s best for everybody.” Bradley liked playing the authority, which made admitting failure difficult. He made a halfhearted stab at a local college but quit after failing a final. “He was used to everything coming easily and seemed shocked that he didn’t know everything,” said his aunt. To ZJ, however, he related a more flattering version. “i spent a semester at montgomery college in maryland … shuffling 2 and 1/2 jobs and covering old topics, and still not being able to afford it … it didnt pay off.”

Bradley was adrift, which in his father’s view, at least gave them something in common. “You know, I was going nowhere when I was your age,” he told Bradley. To Brian’s mind, the military had set him straight: “Everything’s been fine since.” Bradley had no desire whatsoever to enlist, said Brian. “I spent weeks and weeks and weeks talking to him, encouraging him, because this, you know, falls back to my days,” he told me. “I finally convinced Bradley to talk to the Army recruiter.”

From his barracks in Fort Drum, Bradley concocted a more satisfying story for ZJ—on the web, he controlled the narrative. “somehow one of my resumes ended up in an army recruiters’ hands … and came knocking at my door.”

Either way, Bradley followed in his father’s footsteps, and in 2008, he graduated from intel school, just as Brian had. “I was as happy as a father could be. I was so proud. And patting myself on the back, saying, ‘I made the right decision in doing this,’ ” he told me.

Then, having set him on course, Brian dropped out of his son’s life again. “I didn’t hear one word from him when he was in Fort Drum. So I never knew exactly when he went to Afghanistan. I’m sorry—Iraq. I didn’t even know that he’d gone.”

Bradley entered the Army with a plan. He was going to use the system and not vice versa. The Army would pay for college. He’d “get credentials so creepy conservatives can’t attack me.” But the Army had its own agenda. Bradley believed in the mission, but the Army seemed creepy to him, like a brainwashing cult intent on breaking him down, “correcting every eyetwitch,” he wrote. To begin, it set out to suppress his digital self. “the army took me, a web dev, threw me into a rigid schedule, removed me from my digital self,” he wrote to ZJ. “The army … threw me in the forests of Missouri for 10 weeks with an old M-16 Reagan-era load-bearing equipment, and 50 twanging people hailing from places like Texas, Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi … joy,” he told ZJ, and later added, “what the hell did I put myself through?”

Manning was desperate to escape Army life, even for a few hours, as he told ZJ. And on weekends, he would slip out from under the Army’s watchful eye. He road-tripped to Boston, where he fell in with a friendlier crowd, some of whom were gay. Manning, who’d been rewriting video-game code since he was a teenager, met intense, idealistic young programming wizards, many from M.I.T., a school he’d dreamed of attending. They styled themselves “ethical hackers.” They were awkward, proudly unbathed young coders who nonetheless gave off the cool vibe of people sure of their power. They didn’t damage the digital systems they sneaked into, though they could have. We can “bend networks to do practically anything,” one hacker told me.

In Boston, Manning found another escape. He met Tyler Watkins, a neuroscience major at Brandeis University—another science nerd—and fell in love: “he’s so zany and cute,” he told ZJ. “he bought me a dozen roses, and i bought us matching equality bracelets to wear” for Valentine’s Day. From Fort Drum, Manning obsessed about every detail of the long-distance romance. At 1:18 a.m. one Monday in March 2009, he confided in ZJ.

“I discovered something about my boyfriend tonight,” Manning wrote. “We took a quiz together … well, when it came to who is most important [person] to our lives, i answered with his name.”

Watkins didn’t reciprocate.

“His response was god,” Manning wrote.

“Oh dear,” said ZJ.

“Awkward?”

“Quite.”

“i just hope itll be okay, because i love him.”

For Manning, nothing was okay. In October 2009, he arrived at Forward Operating Base Hammer, a dusty backwater 40 miles from Baghdad. There, Manning felt more isolated than ever—“it’s awfully stressful, lonely.” Intel analysts sometimes worked fourteen-to-fifteen-hour stretches in “a dimly lit room crowded to the point you cant move an inch without having to quietly say ‘excuse me sir,’ ‘pardon me sergeant major,’ ” he wrote. “cables trip you up everywhere, papers stacked everywhere …” Usually, there was a large central TV screen where an analyst could watch the war play in endless loop. You could zoom in on the raw footage from helicopters or even helmet cams. At times it felt like watching nonstop snuff films. “It’s groundhog day,” Manning wrote: every day the same. Later, his supervisors said he displayed dissociative behavior, his mind in one place and his body in another—but that was the nature of the job. An intel analyst sat at his work station and targeted the enemy, reducing a human being to a few salient points. Then he made a quick decision based on imperfect information: kill, capture, exploit, source. Any illusions Manning had about saving lives quickly vanished. At one point, he went to a superior with what he believed to be a mistake. The Iraqi Federal Police had rounded up innocent people, he said. Get back to work, he was told. “I was never noticed,” he later said.

Meanwhile, Manning’s concerns about his sexual identity were intensifying. In November 2009, he made contact on the web with a gender counselor back in the States. When I met the counselor, he was easygoing and upbeat for someone who’d spent hours talking to servicemen who believed they were inhabiting the wrong body. He knew what he was talking about, though. In person, his gender was difficult to discern—he’d begun his transition as a teenager. “Bradley felt he was female,” the counselor told me. “He was very solid on that.” Quickly, their conversation shifted to the practicalities: How does someone transition from male to female? “He really wanted to do surgery,” the counselor recalled. “He was mostly afraid of being alone, being ostracized or somehow weird.” To the counselor, it was clear Manning was in crisis. “I feel like a monster,” he’d typed on his computer several times. The statement referred partly to his gender struggles but more to his job. He’d taken an oath not to divulge this type of information. But then it spilled out. He told the counselor about a targeting mission gone bad in Basra. “Two groups of locals were converging in this one area. Manning was trying to figure out why they were meeting,” the counselor told me. On Manning’s information, the Army moved swiftly, dispatching a unit to hunt them down. Manning had thought all went well, until a superior explained the outcome. “Ultimately, some guy loosely connected to the group got killed,” the counselor said. To the counselor, it was clear: Manning felt that there was blood on his hands. “He was very, very distressed.”

About that time, Manning later explained, “everything started slipping.” Manning, it turned out, wasn’t built for this kind of war. “i was a *part* of something … i was actively involved in something that i was completely against.” The job wore down lots of soldiers. Some survived by becoming desensitized—the blood and death goes right past them. Manning took it personally. According to the government, it was in November 2009, the same month that he reached out to the gender counselor, that Manning began to work with WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange, “a candidate for the most dangerous man in the world,” as Daniel Ellsberg, leaker of the Pentagon papers, later put it.

Assange’s appeal to Manning was obvious. The WikiLeaks leader was a celebrity in Manning’s hacker world—dashing, mysterious, and cartoonish in equal parts. There was his striking appearance: knife-thin with a constantly cocked head and that saintly white hair. Assange was another one who’d harnessed the power of the Internet to do his bidding. He was a genius programmer and cryptographer who started refining those skills as a teenager. As a 24-year-old, he was charged with hacking into Nortel—he didn’t cause any significant damage and so wasn’t sentenced to prison. Hackers loved him. To them, he embodied all their best impulses. They thought of themselves as “highly critical minds that question authority, appreciate civil liberty,” one hacker explained to me. And Assange questioned authority every day. But Assange wasn’t a typical hacker, who, after all, are mostly technicians. Assange was a thinker. One of his central thoughts was that secrets sustain corruption. And so he designed WikiLeaks, which made leaking the world’s most closely held secrets devilishly simple. Just hit SEND and off they went into WikiLeaks’ encrypted system.

“I feel like a monster,” he typed to his gender counselor, who said, “He was very, very distressed.”

For months, Manning later said, he tracked Assange, and eventually, he claimed, the WikiLeaks founder responded. “He finds you,” Manning later explained. It was something like a courtship, at least from Manning’s point of view. “i’ve developed a relationship with assange,” he wrote. Assange’s attentions flattered Manning, and his beliefs spoke directly to the troubled, impressionable private. “Every time we witness an act that we feel to be unjust and do not act, we become a party to injustice,” Assange once wrote.

The seduction worked both ways. For Assange, someone like Manning was irresistible, too. WikiLeaks had revealed political and banking scandals in Kenya and Switzerland, but a person like Manning had access to more impressive secrets, involving the United States, a central perpetrator of injustice in the world, as Assange saw it, and one on which there were few checks.

Manning claimed he was a source to Assange, not quite a collaborator, but he had certain privileges: “i mean, im a high profile source.” To maintain his status in the hierarchy of Assange’s attentions, Manning had to produce, which ratcheted up the pressure. The process exhausted him. “I’m a total fucking wreck,” he later wrote.

Meanwhile, Watkins, one person Manning thought he could depend on, was slipping away. Even before shipping out, Manning had changed his Facebook status to “single.” But it wasn’t a clean break. “Thinking of you dear,” Watkins wrote on Manning’s Facebook page on March 24, 2010—but then disappeared. The mixed signals drove Manning to despair. “[Tyler] left me with this ambiguity for months on end,” and it “causes so much stress,” he wrote on Facebook, according to a copy provided to New York. Manning reached out again and again, but Watkins wouldn’t respond.

Then, finally, he heard from Watkins, who “lectured” him: The relationship was really over. “With closure, there’s at least some peace in this rotten world,” Manning wrote on April 30, 2010. But not much. “What do I have left at home—the answer is clearly Nothing.”

On May 5, Manning wrote on Facebook, he “is beyond frustrated with people and society at large.” His master sergeant had removed the bolt from his weapon—again there was concern that he might harm himself or others. He was telling people he was on his way home to be discharged with an “adjustment disorder,” though “gender identity” had also been marked in his file, according to the Washington Post.

Then, on May 21, 2010, Bradass87 popped up on the screen of yet another stranger, Adrian Lamo, a hacker famous for spectacular intrusions. At the time Manning had reached out to Lamo, he desperately needed a friend.

That day, at 11:40 p.m. in Iraq, Bradass87 sent Lamo an instant message on AOL.

“hi,” he began.

Lamo later provided the chat logs to Wired.com, which posted edited versions; Boingboing.net later posted additional excerpts. According to the logs, Manning didn’t take long to make a startling statement: “hypothetical question: if you had free reign over classified networks for long periods of time … say, 8-9 months … and you saw incredible things, awful things … things that belonged in the public domain, and not on some server stored in a dark room in Washington DC … what would you do?”

Lamo seemed to be the perfect confidant for Manning. He was a celebrity in the hacker circles with which Manning identified, and he’d worked on a task force for gay, lesbian, and transgender youth. He’s bisexual. And then, Lamo, like Manning, lived the most vivid parts of life online.

I wanted to talk to Lamo, and after I tracked him down online, he invited me to the Coliseum, a Long Island motor inn where he greeted me at the door of his small room. He wore a half-smile, quipped that he was staying until he exhausted his finances or died, and made a beeline for the bed—he was unsteady on his feet. And then he shut his eyes. And kept them shut for much of our three-hour conversation. He was articulate, even thoughtful, but didn’t seem entirely present. He often paused for 30-second intervals before speaking.

It was only when I asked about his life as a hacker that Lamo seemed to become fully engaged. “It is the one thing I get excited about,” he told me. Lamo is a high-school and college dropout, but as a hacker he thought of himself as a bold explorer of new worlds, a Columbus. His hacks were at once clever and incredibly dumb—and always sensational. “Why not go in and behave like a user and see what can be made to behave differently than expected?,” he explained. Lamo didn’t damage the systems he entered—“I didn’t want to be malicious”—but left behind a quirky signature, as if to say, “I could have hurt you.” At Yahoo News, he edited a couple of stories. Later, he hunkered down at a Kinko’s copy shop for 24 hours and, with nothing but his laptop, hacked so deep into MCI Worldcom’s computer system that he could have fired then-CEO Bernie Ebbers. “I was tempted,” Lamo told me—but he just took a screen shot.

Lamo’s hacks made him famous mostly because he ran to the press after each one. Unfortunately, the FBI turned out to be an avid reader of his press. In 2003, the government arrested him for busting into the New York Times’ computers—Lamo had added his name to the list of op-ed contributors and created several Nexis accounts, mainly to keep up with news of himself. At the time, Lamo was furious at the government. His arrest “strikes a blow against openness,” he said. Hackers rallied around him. As far as they were concerned, his only crime was “that of outsmarting you”—the government.

In the Coliseum Motor Inn, Lamo lit a cigarette, a Camel with a pellet of menthol in the filter, and sucked on it like a straw. Smoking seemed to make him wistful. “[WorldCom] is a long time ago now,” he told me.

Lamo’s life as a hacker had come to an end at 22, and with it, a part of him seemed to die. He’d been sentenced to house arrest rather than prison, but he told me, “I’ve been diagnosed with major depression that largely began after my clash with the FBI.” (Two weeks before Manning reached out, Lamo had been confined to a mental-health facility.)

If Lamo suffered, he didn’t let on to his public. Hacking was now out of the question, but arrest had enhanced his fame. Young admirers reached out to him, including, in 2007, a 17-year-old named Lauren Robinson. “I liked his ideals and such back then,” she told me. Within a year, they were married—Lamo was 26 at the time. At first the romance was exciting. Soon, though, reality set in, Robinson recalled. “We’d sit around on computers all day,” she complained. As she saw it, his main activity was tending “the Adrian Lamo persona,” which existed almost exclusively online. “Eighty-five percent of his time was on a computer,” she said. He refused to work for pay. “I won’t whore out my skills,” he told Robinson. His father paid their rent. In the real world, Lamo was barely hanging on. But as Robinson, now divorced, recalled, online his reputation was intact. “People kind of saw him as a hacker idol,” she said. Bradley Manning must have too.

It wasn’t even much of a hack, Manning told Lamo, according to the logs. The Army’s “infosec”—Manning used the military term for information security—was so sloppy that a lowly intel analyst could sift through the government’s most closely held secrets. “it was vulnerable as fuck,” he wrote to Lamo. Manning downloaded data onto a CD marked “Lady Gaga,” lip-syncing as he supposedly did his job: “pretty simple, and unglamorous,” he wrote. No one had ever taken note of him, and no one did now: “everyone just sat at their workstations … watching music videos / car chases / buildings exploding … and writing more stuff to CD/DVD.” Then, the government alleged, he fed it to WikiLeaks.

In their online conversations, Lamo wanted to know more and encouraged Manning any way he could. He flirted. The two exchanged photos, assuring one another of their “sexiness,” according to a person who read the unedited portions of the chat logs, sent each other emoticon hearts, and used endearments like “sweetie.”

But Lamo wasn’t Assange, offering Manning a part in a noble cause. Even as he flirted, Lamo contacted a friend connected with military counterintelligence. Lamo didn’t want to find himself on the wrong side of the FBI again. Also, as Lamo saw it, Manning posed a threat to the nation. Manning said he leaked hundreds of thousands of secret diplomatic cables: “holy fracking crap, 260,000 documents, do you think you could go through those and say they’re not going to cause any lives to be lost.”

Lamo, who soon started working with the authorities, led Manning on.

bradass87: “i think im in more potential heat than you ever were.”

“Not mandatorily,” Lamo reassured him.

Manning isn’t a classic whistle-blower. Disturbing information didn’t cross his desk, prodding him to act. Manning snooped—according to the timetable he proposed to Lamo, he’d been at it since almost the moment he arrived in Iraq. “i had always questioned how things worked, and investigated to find the truth,” he said. One of Manning’s first discoveries was a troubling 2007 video of an Apache helicopter attack in Baghdad. In the video, the viewer watches through the crosshairs of a .30-caliber gun—almost complicit—as the gunner killed two Reuters journalists, mistaking a Telephoto lens for a weapon, and wounded two children. For Assange, the meaning of the video was clear, and to make his point he edited the video into a version he called “Collateral Murder.” It caused a worldwide scandal and overnight gave WikiLeaks, a tiny group of activists, credibility.

“What is your endgame?” Lamo asked Manning.

Manning didn’t have one. He’d started leaking as a way to protest the conduct of the war. The Apache helicopter killings were “wrong,” he wrote to Lamo. But soon he embraced a broader principle: Open the drawers. “information should be free,” he told Lamo, reciting the hacker mantra. According to the chat logs, Manning said he leaked Iraq and Afghan war logs, reports on Guantánamo prisoners, and a cache of diplomatic secrets. “explaining how the first world exploits the third, in detail, from an internal perspective,” Manning thought of himself as honorable, even heroic—“I guess I’m too idealistic,” he said. “i want people to see the truth … regardless of who they are … because without information, you cannot make informed decisions as a public.” He hoped to provoke “worldwide discussion, debates, and reforms … if not … then we’re doomed as a species.” He added a personal coda: “i will officially give up on the society we have if nothing happens.”

Lamo played Manning, reassuring him while, in reality, he had nothing but disdain for him. When Lamo was arrested, he’d been offended by the government prosecution—“criminalizing curiosity,” he called it. Now he was offended by Manning. “He’s a traitor at best,” Lamo said. And, worse, a child. “He was almost eager to explain his leaks, current, past, and future. Like a kid showing off a new toy,” Lamo told me. He was disgusted by the way in which Manning conflated his own precious moral awakening with the future of U.S. diplomacy. The leaks could “compromise our ability to make the world a better place, which we do in a lot of ways,” Lamo later said.

Manning explained to Lamo that he had targeted innocent men, as if that justified a seemingly endless leak of government secrets.

“i was a part of it … and completely helpless.”

“sometimes we’re all helpless,” responded Lamo cheerlessly.

With Lamo, Manning seemed to boast sometimes, but at other points he seemed on the verge of tears: “i just wanted enough time to figure myself out … to be myself … and be running around all the time, trying to meet someone else’s expectations.”

Lamo couldn’t muster any sympathy. A little later, Manning wrote, “im not sure whether i’d be considered a type of ‘hacker’, ‘cracker’, ‘hacktivist’, ‘leaker’ or what.”

Lamo offered another possibility: “or a spy :),” adding a smile.

On May 26, five days after Manning contacted Lamo, the Army moved. Manning was arrested in Iraq. Almost two weeks later, Lamo, who couldn’t ever resist the spotlight, leaked the story to a journalist and ex-hacker at Wired.com. And once again, he was famous.

At the Coliseum, the overhead light was dim. Cigarette smoke hovered near the ceiling, lending our conversation a conspiratorial air. “I’m a defector,” Lamo said with loopy pride. He meant to his fellow hackers, and indeed, Adrian Lamo is their Benedict Arnold. “Every single day, ten people are telling him he’s a shit,” said one friend who’s sympathetic. “Nobody respects him anymore.”

For Lamo, though, defection came with benefits. He lost one community but gained another. Lamo’s celebrity as a hacker had been waning for years. Now, once again, he felt like a force to be reckoned with. He was summoned to Washington. “At one meeting, you had the Department of State, Department of Defense, the Army Cointel, the FBI, National Security Section, NSA, and like two or three other guys,” Lamo told me, as his delicate hands twitched in his lap.

It was difficult to imagine Lamo nabbing a spy. “I can’t imagine you holding a real job,” I told him at one point.

He smiled, revealing a missing tooth. “You’re not wrong in that,” he said. “I haven’t held a real job in a long time.”

I told him I didn’t understand why the government even needed him. They have the chat logs. Lamo seemed hurt. He’d come to view himself as part of the country’s counterespionage effort. “Think of it. You’re the government. All of a sudden, out of the blue, you acquire one Adrian Lamo with no strings attached. You don’t just throw him away when you’re done with him,” he said grandly.

I checked the time. It was past eleven and raining outside. I had a train to catch. On my way out, Lamo stopped me. He had a question. “I’m in the market for a place to stay,” he said. He wondered if I knew a couch he could crash on.

Manning was first taken to a jail in Kuwait, then transported to the brig in Quantico, Virginia. There, he was held in harsh conditions, kept in his cell 23 hours a day, and, for a time, made to sleep naked. And yet, while sitting in prison, he became much more powerful than ever before. He became a symbol. Conservative Mike Huckabee called for the leaker’s head—literally: He favored execution of traitors. Glenn Greenwald, the liberal columnist for Salon, argued that Manning was courageous, a latter-day Ellsberg, the ex-Marine who’d leaked a history of government deception during the Vietnam War, though perhaps even more important. “These leaks showed us the true face of American conduct in the world,” he wrote.

Assange didn’t admit that Manning was a source, but he couldn’t quite abandon him. Assange generally cared more for principle than people, whom he considered either useful or not. “I’m not so big on the nurture,” he admitted in a different context. But Manning was special. Before Manning, Assange had been a gadfly, his accomplishments laudable but unheralded. After Manning, he was a hero to some on the left, “the most important person to ever live,” as one of his circle maintained. So important that the military drew up a plan to undermine him (which was leaked to WikiLeaks). The U.S. convened a grand jury to investigate WikiLeaks under the 1917 espionage act. (Separately, Assange is under house arrest in England, awaiting a hearing on extradition to Sweden, where he faces questioning for sexual misconduct.) And the pressure has taken a toll on WikiLeaks. A top lieutenant, fed up with what he saw as Assange’s dictatorial ways, defected to launch his own site—OpenLeaks. Perhaps more important, WikiLeaks’ technology architect departed with him. And so, for the past year, WikiLeaks has been unable to receive leaked documents online.

In prison, Manning was far from the furor he’d set off. He had a few visitors. For a time, Manning’s father was one of them—he apparently wanted a relationship after all. For father and son, though, prison was not a place to grow close. “We talk pretty much all technical talk, and I was quite amazed at how he was current with it,” Brian Manning told me. “He was giving me some advice.” For Bradley, the conversation was little comfort, and two months ago, he took his father off his visiting list. “It’s complicated,” was Bradley’s explanation. His mum managed to visit once from Wales. But she was another stranger. They didn’t have that much to say to one another, and for part of the visit, she just stared at him.

It wasn’t long ago that Manning had imagined a bright future for himself. At Fort Drum, as the rest of his platoon slept, he typed into the night. He might “jump into politics,” he told ZJ casually. His plans were “vague,” but he was determined to have an impact. He assured her that after he got out of the Army, “im planning on breaking out in all directions.” Manning, now 23, faces 52 years in prison, and perhaps the death penalty. But in other ways, his reach is longer, his footprint wider than he could have ever dreamed. He’s already broken out.

See Also:

Manning and ZJ’s IM Chat Logs

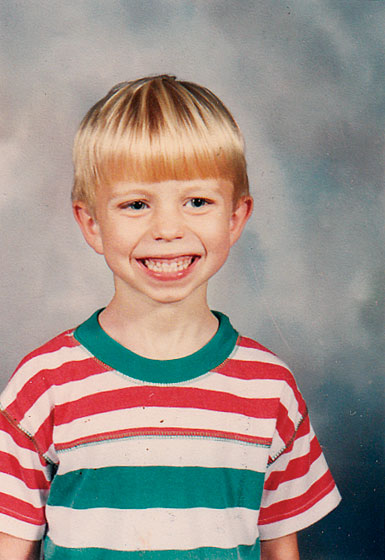

Manning as a 6-year-old, circa 1993. Photo: Courtesy of the Manning Family

Manning with his sister, Casey, in Las Vegas for her wedding in 2004. Photo: Courtesy of the Manning Family

Manning with then-boyfriend Tyler Watkins. Photo: Splash News

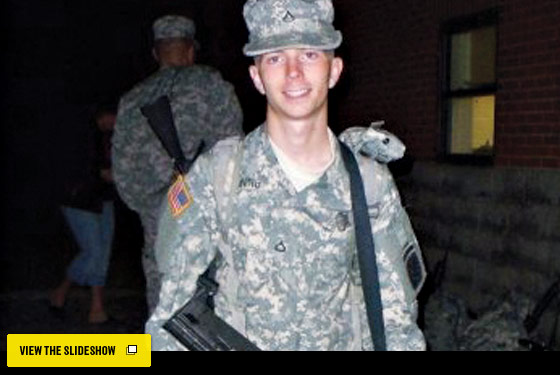

Manning as a soldier. He felt that the Army was a brainwashing cult. Photo: Courtesy of the Bradley Manning Support Network

Crossdressing blogger and Manning confidant ZJ Antolak. Photo: Courtesy of Zinnia Jones