The streetlights in Buenos Aires are considerably dimmer than they are in New York, one of the many things I learned during my family’s six-month stay in Argentina. The front windshield of the rental car, aged and covered in the city’s grime, further obscured what little light came through. When we stopped at the first red light after leaving the hospital, I broke two of my most important marital promises. I started acting like my wife’s doctor, and I lied to her.

I had just taken the PET scan, the diagnostic X-ray test, out of its manila envelope. Raising the films up even to the low light overhead was enough for me to see what was happening inside her body. But when we drove on, I said, “I can’t tell; I can’t get my orientation. We have to wait to hear from your oncologist back home.” I’m a lung doctor, not an expert in these films, I feigned. But I had seen in an instant that the cancer had spread.

PET scans are like that, radioactive tracers that travel around the body and measure how much work different cells are doing. And cancer cells are very active workers. The scans are like the ground seen from the air at night. When there is no cancer they look like Idaho, all quiet. Really bad news looks like downtown Chicago or Phoenix.

It was a warm night for early June, the beginning of the winter in Argentina. People crowded the sidewalks, returning from work, stopping for dinner. All the everyday stuff that fills our lives, neither adding particular meaning or taking it away. We pulled into the garage with the narrow entrance; our tires squeaked on the newly painted floor. Ruth was silent. I was silent. I knew. She didn’t.

Actually, she probably did.

My wife was dead eight months later. We were back in New York. In our home. During our winter.

It didn’t take long for those films to be examined and interpreted by doctors at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the hospital where I’ve been a doctor for more than a decade and where Ruth had been treated when she was first diagnosed with breast cancer, three years earlier, in 2008. Only a few minutes after we parked the car, the phone in our apartment rang. It was the oncologist.

Ruth and I sat next to each other on the couch, each with a handset. The oncologist used many words familiar to me—metastasis, emergency radiation, focusing on “quality of life,” not cure. Technical jargon sneaked into my questions as Ruth’s name disappeared from them. “Could she develop cord compression?” I asked. Then her voice. “What’s that?”

Ruth’s doctor never made us wait. No gentle approach, no layer of euphemism obscuring the truth, no gingerly poke and quick retreat from the scary thing over there. He filled in answers to unspoken questions. “There’s a lot we can do.” “This is manageable.” “You might have many years.” But then circling back. “It can’t be cured anymore. Our goal now is to slow down the cancer and give you as much quality life as we can.” To paraphrase, the films meant Ruth was going to die.

When I relayed that conversation to my friends, many of whom are cancer doctors, they were pretty surprised. What Ruth’s doctor had done was unusual, or maybe even inappropriate, they told me—delivering bad news, especially over the phone, before it needed to be conveyed. When I asked them when the right time was to tell someone that death is unavoidable, they most often told me that the moment occurs after several successive attempts at stopping the cancer have failed. Only then, when the patient is cornered by cancer, that’s the time.

Doctors claim that patients aren’t ready for the bad news earlier, when they are still digesting their shocking predicament: that their lives have changed irretrievably; that their priorities, their future aspirations, their promises to their loved ones—both the explicit and, more important, the implicit ones—would go unfulfilled. They cite their own hesitations too. Doctors want to be purveyors of hope rather than despair, a motive sometimes attributed to compassion, sometimes to a starker concern that patients will find a new, more optimistic second opinion.

I’m a fan of bluntness, but I know it can be detrimental when a patient isn’t ready and can cause confusion when other doctors are shimmering with lighter scenarios. Ruth’s doctor may have done the right thing despite what my friends were telling me. There’s a famous report from the Institute of Medicine showing that nearly all adults say they want doctors to share what they know, even if the news is bad. Ruth had expressed this sentiment to me many times, as in “I don’t want my doctor knowing something about me that I don’t.”

As we sat on the couch, four inches or so separated her right thigh from my left. She moved her nails through her blonde hair. She had a new manicure that day, a dark red. I tried to sense what Ruth was hearing through the air that separated us. No doubt she wondered what was happening in my head. But she couldn’t have known that I wasn’t really listening at all.

She was as healthy-appearing in that moment as the day I had first met her at the Baltimore Symphony, 17 years earlier. As beautiful too. But as I glanced over at my dear wife, I saw the people I have cared for over many years on the tenth floor of Memorial Sloan Kettering, where our breast-cancer patients go. Ones emaciated, ones yellow from liver failure, ones bloated with anasarca fluid ballooning their extremities, ones delirious from kidney failure, pain medications, and metastases in their brain. Some Ruth’s age, many more older. Ruth was 46.

I realized that I now had a secret we couldn’t discuss. I could see her future. Where she would end up. What she might look like. How she might suffer with me standing helplessly by her side. She couldn’t.

Her oncologist snapped me out of it as he started to talk about her back pain in more detail, telling us we had to get her to New York. Soon. And, zing, I switched into doing mode. A lot had to happen, and Ruth and I set about making our lists.

She would go first. Our son had only a few days left at his school in Argentina, and then there was the end-of-second-grade graduation party with the bouncy house, which Ruth did not want him to miss. After that we’d follow.

Her doctor told us not to panic, because treating her cancer was not urgent. In fact, he said there was no real rush because she couldn’t be cured anyway (in case we had missed that point). The spine was another matter. It was the one place her cancer had spread that might become unstable.

The spine is like a pile of those cheap plastic poker chips with the little ridges. Perfectly stacked, they’re strong enough to hold enormous weight. But if cancer eats away in just the right place, it can cause a small kink, and then pressure leads to collapse. Because of where the cancer was, her spine could shift, even slightly, and that might take away her ability to walk or to control her bowels. She needed to get home.

Friends and family would meet her at the airport, go with her to the urgent-care center at my hospital, be at her side when the neurosurgeon came by to see her. If we were lucky, he would say her spinal column was sturdy despite the tumor. If we weren’t, she’d then enter my hospital as a patient, to the IV poles that rhythmically dripped out medications. To the X-ray machines mounted on walls and the gray drug dispensaries that huddle at every station like ATMs, waiting for nurses with special magnetic cards to come by and remove small aliquots of narcotics and sedatives that would then be ferried through doorways and to patients who are not visible from the halls. To the land of the sick, the place where I only travel with my white coat, where I use technical words that break down human suffering into its component parts.

Four hours after Ruth landed at JFK, she was scheduled for surgery. I was left behind, watching late-night Argentine television that I didn’t understand as our son slept. I sent emails and hundreds of texts, trying to explain to our friends what was happening, masking my fear with mordant humor. To one of my college roommates I texted, “I’m utterly bereft.” He lovingly pinged back, “I don’t know what to say,” and a moment later another ping: “Yes, I do. You can’t modify ‘bereft.’ ”

When I finally got to New York and Ruth was through her emergency surgery, our slow summer began. Ruth had pains. “Like a fist twisting my intestines,” she’d say. “Like a mule jumping on my spine.” I’d ask, “How do you know?” and she’d laugh. One month passed, she got stronger, and a scan showed the vertebral bodies were free of cancer. The treatment had worked. Ruth had been propped back up after she had teetered.

The cancer wasn’t gone, but it had been eradicated from the one place it threatened her in the moment. Then her doctor started her on a hormonal pill, a common first step in many cases for women whose cancer is fueled by estrogen. He was optimistic she could be on the pill for a while, maybe even years, if it worked.

Ruth started to go online to find stories of women who had miraculous recoveries; she often spoke of one who was reportedly into her 14th year, and counting, with metastatic breast cancer. In 1994, writer Marilyn Greenberg wrote an essay describing all the women she was told about while she was being treated for breast cancer. Her “phantom rivals,” she called them. Those other breast-cancer patients, who during their treatment played tennis, walked the runway, and made love as she lay anxious and nauseous. This 14-years-and-counting woman was Ruth’s phantom rival, and mine. Our hope and our enemy.

We went back to our lives. Focus on the small things. Go to the beach. Look at the sunset. Dip our toes in the water, or maybe go in up to our knees. This is the mantra of many people who are sick, and it became ours. She would have good days and bad days, just as long as we kept having days. When Ruth recovered from her surgery and radiation, she went back to work at her bank.

To even her closest friends, she was the same smiling, funny, silly, thoughtful woman I had met and then married. The petite woman who had joked about how her wigs made her look like a miniature transvestite when she was getting treated the first time for her cancer, or who, when she removed her wig to reveal her bald head before bedtime, laughed when I told her I felt like I was having an affair with a white supremacist. But even from across a room full of people, I saw that Ruth’s smile had changed. Her top lip was not pulled quite as high as it used to be. It was down less than a millimeter, maybe about half a millimeter, a distance so imperceptible to anyone else I can’t even remember what something less than a millimeter is called.

I saw in that lowered lip, that half-smile masquerading as a full one, a secret tell. She was in deep pain, privately pondering an imminent darkness, knowing that we no longer had an uncountable number of nights and days ahead. We had a pretty small number instead. Micrometers, that’s what they’re called.

One day late that summer, just before Hurricane Irene, Ruth told me she was sorry to be leaving me. To know that she would be causing me so much pain. Best I could muster was, “Yeah, me too.” About that time my father died unexpectedly. Ruth burst into tears. So did our son. I didn’t flinch—I had already been ripped up by the roots.

Then, in early autumn, Ruth’s doctor sat us down to tell us that her “tumor marker” was elevated for the second time in a row. When these markers—counts of chemicals in the blood—rise, it means the cancer could be growing, and the treatment isn’t holding it back any longer.

Her doctor sat at his desk, half-turned to us, as he looked at her test results on his computer. He was quiet as he reviewed them. Then a decision was made. Ruth would stop the hormone pill, which was mild, and get much more toxic treatment with chemotherapy instead. Cancer doctors receive a lot of criticism for how easily they take this step, deciding to dole out chemotherapies with side effects like nerve damage and overwhelming fatigue, some of which never go away. At times, even cancer doctors will confess that they can have an overly narrow agenda of making the cancer shrink, or, in this case, of making some blood test change when the path to doing so may harm their patients.

As he wrote out the prescription for her to start the next treatment, what doctors call “second-line treatment,” I recalled a colleague of mine explaining the progression from first-line to second-line to third-line treatment. Each successive change brings more side effects with less chance of benefit. As my colleague put it, the cancer gets smarter, the treatments get dumber. Somewhere in this progression the trade-off no longer makes sense. Where that is may differ for each patient, but I’ve often thought that cancer doctors go well past that point.

None of that mattered to me, the medical professional to whom all these nuances and trade-offs should. All I could think about was the blood test telling us the tumor marker was too high. With that, any dreamy conceit—that patients should be given enough knowledge that they can weigh the risks and benefits for themselves, then come to the choice that best suits them—flew out the window. Our choice wasn’t a choice. Take the chemo.

Ruth’s doctor explained the mechanics: also a pill, but this time Ruth had to take whole handfuls of them several times a day. Just how bad the side effects got would dictate how much she would be able to keep taking. It wasn’t going to cause Ruth to lose her hair again, we were told. That was a relief, although I knew we still had her wigs from last time. We had resolved to keep them until she was out five years, thinking it bad luck to discard them earlier. There is one with auburn hair still in my dresser. One of the enchanted objects she left behind.

Ruth’s oncologist, as always, was blatantly direct about the fact that the chemotherapy might not work at all, or might just cause her side effects so quickly that she couldn’t get enough in her system. So we had another abstract goal—see if she could tolerate a lot of the pills without getting too sick. That would be our victory on the road to defeat.

We left his office and got into the elevator. There were maybe half a dozen other people already onboard as we turned toward the closing doors. One was another doctor in a white lab coat whom I had known for more than a decade, and I muttered a hello before I looked away. Two or three were patients with family members. I wondered where they were in their cancer process. In shock, counting the days, or on the other side and cruising? When we got to the lobby Ruth tilted out the east exit to get back to work and as far away from the cancer as she could. Then she was gone.

Writer Daphne Merkin once described depression as a thick black paste covering one’s life. But it didn’t actually feel like that, nor was it a goop from a sci-fi film after the alien explodes. It was a coating, a thin translucent layer, invisible to the outside, hard as a diamond, and in that moment I couldn’t tell if it was holding me together or smothering me, but either way it was isolating me from the bustle of the lobby and the living world. There was also a feeling, welling up, that was totally unexpected. An urge I can barely admit even today. I knew, with certainty, that I would soon be confronting an emotional abyss that I could see just ahead. And I had this strong desire to run toward it. To just get on with the sorrow.

When Ruth was first diagnosed with breast cancer, friends would routinely comment to us along the lines of “It’s so good Peter knows so much about this disease.” But others disagreed, imagining I suffered more from my knowledge. Whether I was better or worse off I kept filing away as a pointless academic debate, like wondering if Edna Pontellier’s death in The Awakening was a resignation or a liberation, or whether Batman would ever just get over it. But in the lobby of my hospital, I knew the answer: My knowledge was too clear-eyed. I couldn’t pretend for another day or hour or minute that there were good days ahead.

For the next month, Ruth set about her business, as if taking fistfuls of pills and slathering on foot cream, intended to prevent a skin reaction from her chemotherapy, was just something anyone does in the normal course of their lives. She continued working at her job, in large part, she explained, because she enjoyed it, but also because she was sure she would die if she stopped going. She didn’t mean it metaphorically.

It is often argued that life-threatening illness imbues its victims with a new vigor for life. I’ve always found this notion sort of idiotic, a ham-handed attempt at ennobling illness, which deserves no such credit. As Ruth saw it, she already had a life she did not wish to part with. She didn’t need to construct a new one just because there wasn’t much time left. Meanwhile, as she went about the daily routine, I was indulging myself in my own personal thesaurus entry for bereavement, endlessly contemplating the inevitable, teleporting forward to a time when she would suffer, and then to a time when she would be gone.

With November, Ruth began to fade. Her second-line treatment was working maybe a little, or maybe it wasn’t slowing down the cancer at all. We would never know. But she kept popping the poisonous pills because there was nothing else to do. As it got colder outside, we started to live less and fake it more. When our friends saw Ruth, they’d hide their shock artfully. One noted that she looked even more beautiful with the weight loss; her face now thinned, her lovely brown eyes were in fact very prominent (for about a year her ringtone was “Brown Eyed Girl”).

One night Ruth dreamed that she was on an airplane in turbulence and a bad jolt ripped off a wing. In mid-November she emailed me from her office to tell me that she felt like every day she was climbing a mountain. About that time she developed a new complication: abdominal swelling.

At first it was only a small amount. Maybe it’s just constipation, we honestly thought, and then stuck to the theory for maybe a week or two longer than was reasonable. The first tests her doctor ordered showed nothing particularly wrong. He thought that maybe it was just some fluid buildup as a side effect of the chemotherapy pills, even though that wasn’t something he had seen happen before.

After another week, we went to see a specialist. On his screen was a CT scan of Ruth’s abdomen. I didn’t need a radiologist to help me with those images. I have looked at thousands of similar scans in my career.

In the seat next to me, in a matching chair, was the woman I loved, my effulgent bride. Just to her right, glowing on the screen on her doctor’s desk, were her photo negatives, a series of images showing the insides of a dying cancer patient. The cancer was clustered in the hip bones, behind the bladder, next to a kidney, near her pancreas. Much of the liver was no longer liver but was cancer instead.

We were told for sure that the swelling was due to fluid collecting around her abdominal organs. The possible explanations for it jumped into my mind automatically. It was probably because her liver was no longer working well, as one of the liver’s central roles is to filter the blood. But when it can’t, fluid backs up and seeps into the abdomen. It’s often deadly when this far gone, because it means that the liver cannot clear toxins from the blood. There were also a few outlier possibilities that were less deadly, and I started to feel desperate for one of them instead, even though if she were my patient I’d have given them no credence.

To manage the pain that now came, she was put on oxycodone, which she started calling “oxys,” as in “I just pop a couple oxys before I go to the office.”

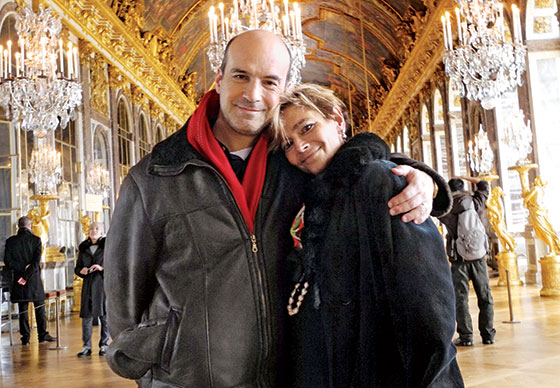

It may seem surprising that it was around this moment of uncertainty, a point when it took her an hour or two to get out the door in the morning rather than her usual 12 minutes, that Ruth decided we should go on vacation over the Thanksgiving week. Splurge. Rent a house in the Caribbean. Invite all our friends and family. It was just another way for her to go on living like she always had (the next month we went to Paris). My one objection to going—that we would be far from her doctors—was met by Ruth in her typically logical way. “What could possibly go wrong that hasn’t already?”

Down there in the sun and occasional bursts of rain we splashed and lounged. We went on a difficult hike, which ended at a secluded beach. It was there that she instructed me to leave her ashes someday. We went sailing, even though it took two of us to help her on and off the boat and three of us to get her in the water to snorkel. But she did that, too, with our son. We even saw a small shark and two turtles. Later that afternoon Ruth led with the singing and cut our son’s birthday cake at sea, and we all overwhelmed him with presents. The theme was “Spider-Man.”

The swelling got worse after we got back home. Gallons and gallons of fluid were collecting in her belly. Strangers asked her if she was having a boy or a girl. She derived some morbid pleasure by responding that no, in fact, it was from her cancer. If they lingered too long, she added, “My doctor says it’s incurable.”

When the fluid and weight gain and abdominal swelling got to a point that Ruth couldn’t really get around, the doctors started removing it just to help her stay mobile. It’s a procedure, paracentesis, that I’ve performed many times. A small catheter is put through the wall of the abdomen and into the abdominal cavity where the fluid is located, and then the fluid is drained through tubing into vacuum bottles.

The first time Ruth had the procedure my heart leapt at what I saw. It was the only moment where my medical background brought me something other than despair. When the fluid started to flow, it was obvious it was opaque, like lymph fluid, not clear like the fluid that collects from liver failure. Her cancer was still consuming her, of course, but it gave me hope that what seemed a deadly complication was instead a manageable one.

If it had been lymph fluid collecting, that would have meant that the lymph channels were obstructed and she could have a shunt put in, a meter-long silicone tube that goes into the abdominal cavity, then is tunneled up under the skin, over the collarbone, and then back into the circulatory system above the heart. It’s a serious procedure with serious risks, including bleeding or a tear in the intestine, either of which can lead to emergency surgery. I knew of this risk, and many others, even as I watched the first gush of the opaque fluid fill the drainage bottle, but from that moment, I wanted that shunt, and nearly insisted it be put in.

I envisioned the nutrient-, electrolyte-, and calorie-rich fluid that doctors had been removing instead flowing back into her bloodstream and magically reconstituting her. She’d gain back the 20 pounds she had lost in the past month. Her cheeks would fill out. Her wedding ring would stop slipping off her thinned finger.

Her doctors were hesitant, seeing the shunt more as a last resort. So into December, Ruth went regularly to the hospital to have the fluid that had built up repeatedly drained. Each time it worked, returning her, as she put it, back to a first-trimester bump. But each time I felt we were delaying the inevitable when we should have been fighting for a chance at a bright future, a period where she would regain her strength and vibrancy. Yes, there were huge risks. She could die from the shunt. But why not go for it because she was going to die without it?

We were finally caught in cancer’s Zugzwang, the point in the game where all possible moves make you worse off. The point that the other 40,000 women each year who die from breast cancer in the United States also encounter in one way or another. I will never again be mystified, as I had been with many patients, by why someone who is at the precipice of death seeks out yet another shot at treatment, even with something harmful that has a near-zero chance of helping. “Why not?” was suddenly a winning argument.

So her doctors put in the shunt, right after Christmas, and she nearly died. Once the fluid from her abdomen hit her bloodstream, her platelets—small cells critical for clotting—started consuming themselves. A normal person has a platelet count of 150,000 to 400,000. Before the procedure, she had over 200,000. Afterward, that number plummeted to 50,000, the cutoff below which the risk of internal bleeding starts to rise rapidly.

Each morning the doctors would come in cheery and bright-eyed, announcing the plan, which was always the same: Keep checking the platelets and see if they hold steady. Other than that, the conversations focused heavily on the shunt and whether it was working. Then the doctors would slide out of the room reiterating their hope that we could keep the shunt in as long as the platelets leveled off, and that they would be back tomorrow.

Ruth would ask all the questions while I sat quietly in the room, listening, not out of politeness or deference but because I knew what was happening. I knew that the doctors would head back into the hallway en masse, and out there they would really talk, the susurrus of their conversations drifting back into our room. They would say what I would: that treatment options were exhausted. That chemotherapy was no longer working, or, in doctor parlance, that Ruth had “failed” chemo. Her breast cancer was now as aggressive as lung or pancreatic cancer. She was terminal. After several days of the same routine, we went home, with the shunt, just in time for New Year’s.

Over the next two weeks the shunt worked in that it kept her belly trim, but Ruth got weaker anyway. My fantasies about weight gain and renewed energy never came true. Ruth’s liver had failed; the fluid, after all, had been from that. One day she stumbled on the stairs and told me it was nothing. Then she stumbled the next day and dismissed my concerns when I gasped. “I’m totally fine, I just wasn’t paying attention.” Then the whites of her eyes, the sclera, turned yellow. I didn’t manage it well.

We were sitting at a coffee shop when the light caught her just right and I saw it. I tried for a few moments to keep talking about whatever topic we had landed on, but I discreetly texted a friend of mine from college, also a doctor, in medicalspeak to share the terrible news—“scleral icterus.”

I couldn’t hold it in anyway. “Your eyes are yellow,” I blurted out.

She was stunned, and slightly panicked. “Why?” she asked. And then something totally unexpected—“What do they do about it?” I seized on this, my escape hatch from having to talk about her liver failing. I said I didn’t know, we’d have to ask. Another lie.

The yellowing, first of the whites of the eyes, later of the skin, is like the check-engine light turning on. The yellowing itself is irrelevant; it means bad things are happening inside. It meant her brain would soon become addled with toxins that at one time her liver could have cleared easily. She was near the end.

My phone pinged. My doctor friend, holding the medical jargon: “Oh fuck.”

A few days later, on a cold Wednesday, Ruth needed to be rushed to her doctor. She was profoundly dehydrated, but when she was given fluids, she became delirious and unsteady instead of feeling more alert. Her doctor stayed with her for an awful six hours, after which I was barely able to get her into our friend’s car and home. But she gathered enough strength for it. And also enough to ask her doctor when she could get more treatment. Her doctor promised that he’d look at her lab tests and think about starting a new chemotherapy.

The next morning, I took the dog out. Like a cheating lover, I went just around the corner from our apartment building, took out my cell phone, and made a brief call.

“I can’t give her chemo, she’s too sick. I can’t do it. It would kill her,” her doctor said.

“Yes, I know,” I told him.

“Okay, thank goodness, you know.”

We both paused. A long caesura. “One of us has to be the grown-up,” I finally said.

He agreed. “But I don’t want to have to tell her there are no more treatments.”

“I know. Maybe we won’t have to.”

When we went to see him later that day, Ruth couldn’t get out of her wheelchair to sit on the exam table, so while I held her hand on one side, her doctor wheeled up next to her in his office chair. He told her he thought it was best to wait another day for chemo.

You might call it a lie, but it was really a feint, leaving open a possibility that was not possible, hinting at an avenue of hope, a glass vial of medicine out there that would come ashore in just a few days if the winds blew as we hoped they would. I sat there, a silent participant in the conspiracy.

Ruth wasn’t buying it. It had been a steep decline, from the photo I took in the fall, when she and our son engaged in their favorite contest of “who can make the ugliest face,” to her now, both gaunt and bloated, yellowed from liver failure, working to get out her words, which came slowly like a drunk drawl. A little slumped in her chair, propping herself up on its arms, she slowly asked those questions no one should have to ask. “How will I die?” “Will it hurt?” “Will my son remember me?”

Our house was full of friends that Saturday. Ruth spent the day on the couch, and in the evening, she told our boy that the doctors couldn’t make her better anymore and that she was going to die. But that he was going to be okay, and so was I. She told him where he would always be able to go to be with her, and that she would always be with him everywhere.

Sunday she slipped into sleep. Sunday night I held her, and I told her it was okay to go, and on Monday she died in my arms. Her last words were “I love you.”

No ghost rose from her body. No ethereal phosphorescent spirit. But it helped to realize that her departure from our lives and from humanity had no relation to what happened next, when the funeral home arrived. The methodical sequence of gurney unfolding and long white bag unzipping, or the physical steps of the zipping up, a pause, and then the nearly silent wheeling away on the large rubber tires. It had nothing to do with her or her vitality. That didn’t fit into any bag.

As her body was removed I reclined on my side of the bed next to her abandoned space, the emptiness of where she had been, my wife, a few hours ago and for many years. That still point at the center of a turning world, a world oblivious to her passing. The comforter was down a little, the sheets in mild disarray, like she had just arisen on any other morning.

Behind me I heard the metal apartment door open, squeak, and click shut. Sounded just like it always did, every time I’d hear the click, open, squeak, close, click as Ruth left for work before me.

The weeks passed, then the months. I don’t remember much of it.

Some days I was nearly paralyzed. Other times I felt this strange dissociative euphoria, like I was playing a game with house money. I had stopped seeing patients when Ruth became sick, and as the months went by after she died I just never put myself back on the schedule. Eventually other work filled in the gap. I think I could do it again some day, but I’m in no rush to be in those halls, looking at scans, reading over platelet counts.

Our life together was gone, and carrying on without her was exactly that, without her. I was reminded of our friend Liz’s insight after she lost her husband to melanoma. She told me she had plenty of people to do things with, but nobody to do nothing with.

It turns out that Hollywood has grief and loss all wrong. The waves and spikes don’t arrive predictably in time or severity. It’s not an anniversary that brings the loss to mind, or someone else’s reminiscences, nor being in a restaurant where you once were together. It’s in the grocery aisle passing the romaine lettuce and recalling how your spouse learned to make Caesar salad, with garlic-soaked croutons, because it was the only salad you’d agree to eat. Or when you glance at a rerun in an airport departure lounge and it’s one of the episodes that aired in the midst of a winter afternoon years earlier, an afternoon that you two had passed together. Or on the rise of a full moon, because your wife, from the day you met her, used to quote from The Sheltering Sky about how few you actually see in your entire life. It’s not sobbing, collapsing, moaning grief. It’s phantom-limb pain. It aches, it throbs, there’s nothing there, and yet you never want it to go away.