Claremont Riding Academy was housed in a converted livery stable on West 89th Street, just off Amsterdam Avenue (think of liveries as equine taxicabs). The riding ring was on the main floor of the building, and the horses lived both upstairs and downstairs, in stalls the size of parking spaces. When it was time for your lesson, you’d wait at the top or the bottom of the wooden ramps and listen for the name of your assigned horse, which would then come walking up or down the ramp to greet you.

I was what was known as a “barn rat,” though I was never one of the central figures in the barn-rat social scene. There was Audrey and Chloe and Jenny and Maya and Sydney and more, girls who went to different schools than I did (many went to all-girls schools; make of that what you will). We currycombed our favorite horses, picked out their hooves, mucked out their stalls, watched each other’s lessons. The instructors rewarded us by sometimes letting us polish their leather goods, too, or braid our hair.

My favorite instructor was Pam, a tough girl with a Rottweiler named Pandora who was often around the stable. She hung out at the Raccoon Lodge, a biker bar down the street, and had long curly hair down to her butt. Maybe because of her no-nonsense attitude, Pam appealed to the celebrities who wanted to learn to ride, leaving all of us one degree of separation from some famous faces. Pam taught Robin Quivers, Howard Stern’s sidekick, and Matthew Broderick, who I didn’t yet care about, being too young to appreciate Ferris Bueller. I do remember that Broderick had a hard time keeping his heels down, an elementary riding mistake, but we were all more interested in the horses.

The horses were named in clumps—Cinzano arrived with other boozy horses, Acadia with other national parks, Willow with other trees. Riders were permitted to take certain horses onto the bridle paths in Central Park, which required crossing two major avenues and stopping at the traffic lights as if you were on a very large bicycle. People would gawk at you on the sidewalk, and mothers would point you out to their children. It was a powerful feeling, one that I took very seriously. The horses were bigger than all of us, and stronger. Occasionally horses who had gone to the park would return riderless.

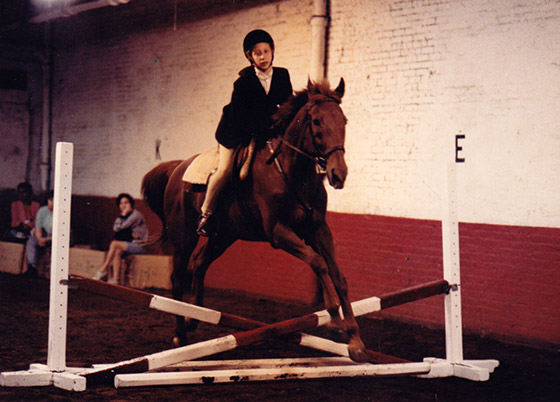

People love to make fun of young girls for loving horses—lots of hymen-breaking jokes there—but it was a glorious feeling, even in Claremont’s tiny ring, to zoom around at full canter, telling this enormous beast underneath you what to do, and having it listen. I fell off a few times, of course, but so did everyone else. That didn’t matter. What mattered was that your head avoided hitting one of the large structural poles that were holding up the ceiling, and that you didn’t get trampled by somebody else’s horse.

Then came puberty. I drifted away from Claremont during my first year of high school, trading my saddle soap for cigarettes, though sometimes still I smell the phantom horse sweat. Though I continued to take lessons once a week, and then less often, throughout that fall, the world of Claremont began to feel like a giant dollhouse that had little to do with my new life as a teenager, too quaint. Horses were for little girls, and I wanted to be sophisticated and adult. The barn didn’t stand a chance.

Claremont closed for good in 2007, when I was 27—converted into condos. The horses, I heard, went to various places—private barns, the Potomac Horse Center in Maryland. Some girls I knew bought the horses they’d always loved and sent them to the equivalent of permanent sleepaway camp, a home in the countryside where they could live out the rest of their days without dodging taxicabs.

I see the posts on Facebook, the horses still at the very center of their worlds, and I wonder if it would have been possible for me to stay as horsey as I’d been as a child, if I hadn’t been quite so interested in boys and malt liquor. No one can stay a girl forever.