While kids in the suburbs went house to house on Halloween, me and my boys never had to leave our building. 42-42 Colden Street, Flushing, Queens. Six stories, maybe 150 apartments. Since Queens is the most ethnically diverse plot of land on Earth, we had tenants from all over the globe. The whole world in one building. At least that’s how life felt back then. For the holiday, adults in the building had devised a wise trick-or-treating system that even the worst kids followed: Only hit apartments with decorations stuck to the door. Think of the Israelites smearing lamb’s blood on their homes so the Lord’s plagues passed over them. Except with candy.

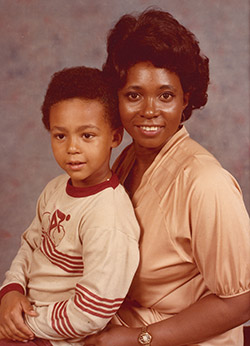

I was 11 in 1983. Too old to be chaperoned by mom anymore, and besides, she always dressed me in these ridiculous professionalized costumes. She was an immigrant from Uganda and aspirational on her son’s behalf. When I was 10, she made me dress up as a doctor. What 10-year-old wants to pretend he’s an ear, nose, and throat man? But I wasn’t entirely above the theater of the day. So in ’83 I snuck out before my mother came home from work. I was dressed like Darth Vader. Vader was my man, even with the villainy. He wore all black and had a deep voice; he reminded me of my uncle. I had a cheap mask-cape combo, the kind available at any pharmacy during October. I remember my two best friends dressing as Stormtroopers, though that probably isn’t true. Our imperial army started on the sixth floor.

At each door with a decoration I rang the bell. My friends held their bags open and I stood with my arms crossed. “Trick or treat,” I said in my lousy James Earl Jones voice.

Each floor corresponded to a letter, A through F. We cleared the sixth floor, the F’s, quick. Along the way we passed kids dressed as E.T. or Rainbow Brite, many princesses. Halfway through the fifth floor we saw apartment E23 ahead. For as long as I could remember, the person in E23 pasted the same Halloween decoration, a witch with a giant wart on her crone’s nose, but whenever kids rang the tenant wouldn’t answer. At first kids figured they’d just missed the guy, bad timing. But it seemed impossible that all of us missed him every year. In 1980 or ’81, kids found that if you rang the bell and stood quietly, you could hear the tenant lurking on the other side. We thought it was weird even then. An adult who lured adolescents to his door so he could peek at them while breathing hard? By ’83 most kids gave up. But would Darth Vader and two Stormtroopers concede defeat? Hell no.

We stood before E23 having made a decision. One we hadn’t even discussed out loud. Growing up in the city, we always felt the frenzied need to grow up. We’d walked to and from school together since we were in third grade and played in packs, far from our folks, well into most evenings. Our parents were working too long and hard to protect us. I’m not saying we were abandoned, but we sure felt like we were on our own.I rang the bell twice. Moments later the faint click as the peephole opened. The three of us held our breath just to be sure that heaving sound wasn’t ours. Once we were sure E23 was at the door, I rang the bell again. And again. And again. But even when our fingers were sore the door hadn’t cracked. And a Sith Lord must know his priorities. We had a whole building to plunder—while we’d been here, kids were depleting candy resources on other floors. We marched away. We’d reached the stairwell exit when we heard the clacking lock, the creak as a door opened.

It couldn’t be! But it was. E23’s door sat halfway open. An old man leaned out. I remember him as ancient, but I’d guess he was probably 35. Me and my boys were paralyzed by the underwhelming sight. Some brown-haired white man.He stepped into the hall. His left arm came into view. His hand clenched into a fist. He cocked it back. “Trick or treat!” he shrieked.

Then the hallway filled with pennies. Pennies flew from his left hand like buckshot. Pennies pinged against the floor, the walls, the ceiling. Pennies clattered as they skipped. But by the time they reached us the pennies slid harmlessly.

E23 stood there grinning. Maybe he wanted to scare us. And maybe he would’ve if the coins had actually hit us. This is one of the things I remember best about growing up in New York at that time. The free-floating anger. A smog cloud of rage. Making everyone, adults and children, prone to bursts of bitterness. And yet I love my home. For better and for worse, I’m a child of this city.

Me and my boys stood by the stairwell door. E23 stood by his. We had other places to be, but I doubt he could say the same. Together we gave him a Queens salute. We grabbed our nuts and gave a shake. “Happy Halloween, motherfucker!” And we were gone.

All 58 interviews conducted and edited primarily by Jennifer Vineyard, as well as by Jessica Pressler and Alexis Swerdloff. Jonathan Lethem and E.L. Doctorow contributed written memoirs.