Chris Smith: What qualities make a great mayor, let alone the best mayor?

John Mollenkopf: How could you be a great mayor without doing a good job of delivering basic services? And the unique challenges of the time: The extent to which the mayor understands those and responds to them creatively is the other half of being great.

Bob Hardt: When you’re a kid, you imagine what would happen when Superman fights Batman, who would win. There’s a similar kind of fun to comparing mayors. How would, for example, Giuliani do if he were coming in 1978 versus ’94? Or how would Dinkins have done, had he come in as the Bloomberg after Giuliani?

Jennifer Cunningham: It’s all context—the right person and the right time come together, and you’re a great mayor. And if you’re not, well, shit happens.

Rev. Al Sharpton: I think what separates good mayors from great mayors is when they’re tested in a real crisis.

Mollenkopf: And symbolic leadership: expressing the city’s values, the bully-pulpit side of it.

Smith: Rudy Giuliani’s allies say he saved the city twice—by driving down crime and then by rallying spirits after September 11. Is Giuliani the best ever?

Sharpton: I am probably the most anti-Giuliani guy in the room, and I think Giuliani set the right tone after 9/11. But even a broke clock is right twice a day.

Cunningham: It might have been a moment of greatness, but I just don’t think you can consider somebody who left so many people feeling more than shut out—disrespected, unimportant.

Mollenkopf: I’m almost speechless at the idea that I could say something admiring of Giuliani. But if you assess the major changes in New York City that happened in the last 30 or 40 years to make this one of the safest big cities in the world, he was absolutely fundamental to making this city what it is.

Smith: Ed Koch steered the city through economic crisis and was a brilliant cheerleader.

Mollenkopf: If you could look only at Ed’s first term or the first half of his span, you would say something different from looking at the whole stretch.

Cunningham: I’m not suggesting it was of his own making, but Koch’s last term was plagued by the worst corruption. It was almost the beginning of the ethics plague that is still playing out.

Hardt: Race relations in the last five years of Koch were pretty lousy. Not necessarily because of him, but he was not the right person at the right time to really deal with a lot of issues that Dinkins tried to confront, also somewhat unsuccessfully.

Mollenkopf: Whatever you think of the Koch administration, the city and the state did put billions of dollars into rebuilding the subway system, and that’s one of the things that’s been fundamental to the turnaround of New York from the downward trajectory that it was on.

Smith: Conventional wisdom says we shouldn’t even discuss John Lindsay.

Sharpton: I remember growing up in the sixties and seventies in Brooklyn. I don’t really remember Wagner, but I remember Lindsay walking the streets in Bed-Stuy and Harlem. Now, we may have been in the toilet fiscally back then, but I don’t remember that because we’ve gone to hell and back ten times since then. But when you say John Lindsay, I have an endearing memory of him because he was a tall, lanky guy who had all the power, and he came to our community.

Cunningham: I also have to stick up for Lindsay. Look at not just what was happening with New York at the time but urban America, with white flight and really no safety net or an urban policy in this country. And if not for John Lindsay, this city would have been living through a situation probably much worse than what Detroit and Newark and other big cities wrestled with. I always thought it was amusing when Giuliani became “America’s mayor,” because America’s mayor was first John Lindsay. It’s just sort of a pet issue of mine. I think the best leaders are the ones who try to encourage people to have faith in public service, faith that government is a force for good, can do right by people. The people we saw go into the Lindsay administration—Mario Cuomo, Carl McCall, and a host of people who didn’t go on to be elected officials—they brought new energy to public service. And I do media for a living, and Lindsay used TV commercials that were pretty sophisticated for their time, the David Garth cinéma vérité, direct-to-camera stuff.

Hardt: PR-wise, Lindsay did everything right, especially his first term. But if you talk to the budget number crunchers of the world, they’ll just shake their heads and mutter, “Oh my goodness.”

Smith: That leaves two big names: La Guardia and Bloomberg. Right?

Hardt: Jimmy Walker [laughter].

Smith: Most fun, maybe. Best ever, I don’t know.

Sharpton: As far as being a flamboyant personality, La Guardia would win on everybody’s scorecard. In terms of how he dealt with a city that was plagued with segregation, particularly in housing, that’s what makes me question whether I could vote for him as the best ever. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. felt La Guardia gave Robert Moses a free hand to build, and that Moses didn’t develop in Harlem and Bed-Stuy, and that a lot of the housing that the city was underwriting didn’t allow people of color to rent.

Hardt: The city was in immense economic and moral crisis during La Guardia’s terms in City Hall. People were living in Central Park in tents. He held the city together; the city actually improved radically under his time. Capital projects that we don’t now recognize as being some of the great works in the city in the twentieth century occurred during his time. And he was that larger-than-life cheerleader character who a lot of New Yorkers could identify with. La Guardia was a great combination of being that cheerleader and also a person who got a lot done.

Mollenkopf: Historians looking at this list, I think, would continue to put La Guardia at the top. But the longer La Guardia was in the office, the more problematic things became, especially in the last part of his mayoralty. Perhaps that’s an argument for term limits. All around, who’s done the best job? I think it’s Bloomberg. Why? He faced very difficult economic circumstances right after 9/11, and he managed to bring the city through that fiscal difficulty without huge layoffs. Without exacerbating tensions. He’s kept the crime rate low without the kind of racial polarization that characterized the Giuliani years. And he’s come up with a whole lot of interesting things that—I mean, we’re starting to take 311 for granted. Giuliani and other mayors wanted to get their hands on the school system and failed to do that, and Bloomberg did. I’m sure everyone wishes they’d made more progress than they have, but there has been real progress in the system. That’s really a major step, it seems to me. And he’s come up with a range of anti-poverty programs. It’s not just symbolic. There’s no other mayor in the United States who’s said, “Let’s address poverty at the local level.” It’s not something that’s in the news a lot, but I think there’s something quite special about it. The city’s belated response to cleaning up the blizzard was not its finest hour and it gave the mayor’s critics a convenient screen on which to project their complaints. But in the end, the impact is likely to be transitory.

Hardt: The larger-than-life, colorful character—obviously Koch jumps to mind. The guy is greeting people on the Brooklyn Bridge during the transit strike, “How’m I doing?,” New York is back. Whether or not it was true, that was the message. Bloomberg buying that $700 bike, it played into the idea that he was an effete guy who didn’t know where Brooklyn and Queens were.

Mollenkopf: Bloomberg can stand in front of a room of highly informed people, critical reporters, people from fiscal rating agencies, and go through a budget, and he knows every footnote to every chart and why the numbers are driving what he does. In that environment, he can be extremely impressive.

Hardt: I think so, but it’s not La Guardia reading the funny pages during the newspaper strike.

Cunningham: But Bloomberg is kind of unabashedly himself. He doesn’t try to pretend he is not a billionaire. He is always telling us how great it is to have a jet. He owns his own personality in a way that … maybe he’s not charismatic, per se, or eloquent, but he’s definitely a personality.

Hardt: And that is New York: “I am what I am.”

Sharpton: Bloomberg ranks high. The problem is the city’s disparity in terms of income. The gap between the life of a wealthy New Yorker, particularly a Manhattanite, as opposed to working-class, outer-borough people has not gotten smaller. That would be the thing that would hurt him. And the blizzard became the metaphor for the perception that everyone isn’t treated equally under Bloomberg, just like in many ways Katrina was a metaphor for the perception that Bush was insensitive to certain people. That perception of Bloomberg is not totally accurate, but the cleanup drove home an image a lot of people had. And Bloomberg’s great-manager image has been snowed under, pun intended. If he’s not overrated as a manager, he at least needs to be reviewed.

Cunningham: Can I interrupt? I’m actually a big fan of Mayor Bloomberg. He is not out of touch. There’s a real willingness to try and grapple with some seemingly intractable problems in the current economic climate.

Smith: The consensus I’m hearing is Bloomberg, with an asterisk.

Cunningham: Let’s make sure that we remember that we’re barely one year into another four-year term. I pick Lindsay.

Sharpton: You can say, with some legitimacy, “La Guardia dealt with a depression, and Bloomberg dealt with a terrorist attack.” But they had a lot of help from beyond the city—from the national government and the state government. David Dinkins was dealing with everything from Crown Heights to the Korean-deli boycott on his own. He created a better tone in a city that was very polarized. It cost him his re-election, but without the qualities he had, the city would’ve been much worse off. He doesn’t get credit for Safe Streets, Safe City, but he set a tone that helped to save the city and did things that paid off later on. Dinkins had to weather the storm alone. That’s why I give him a mark up.

Hardt: The great politicians are the people who wake up in the morning and think they should rule the world. Bloomberg thinks everything should be called Bloomberg. And I think that is a healthy impulse for a mayor, even if it’s delusional among the other 8 million New Yorkers. As long as it’s in check. There’s a narrative with a lot of these mayors of wanting a little too much. Bloomberg is very interested in being on Meet the Press right now, but if you start loving your face in the national mirror too much—I’m not saying running for president, but going for some summit somewhere rather than dealing with the problems here, because you’re bored after giving the same speech for nine years—that could be a problem, where people are sitting in this conference room five years from now, saying, “Wow, that’s great Bloomberg did all these great managerial things, but that third term, he didn’t do much.” So I pick La Guardia. He oversaw the city in a transformative time and became the gold standard for all future mayors.

Smith: Why did I expect agreement?

Sharpton: That wouldn’t be New York.

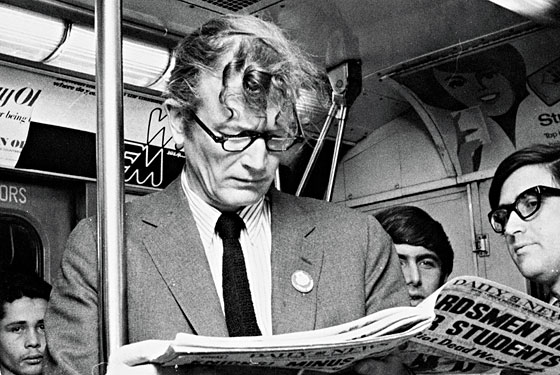

The Arguers

Chris Smith

Moderator

John Mollenkopf

Distinguished professor of political science at the Graduate Center, CUNY, and director of its Center For Urban Research

Jennifer Cunningham

Media consultant and political strategist

Bob Hardt

Political director and executive producer, NY1

Rev. Al Sharpton

Activist