A few weeks ago, on the eve of the lunar Year of the Dragon, New York City comptroller John Liu and myself, two guys from Flushing, sat over $4 bowls of beef noodle soup speaking of our respective boyhoods in northern Queens. There was a generation between us (I’m 63, Liu is 45; I left Flushing to go to college in 1966, six years before Liu arrived), but much mnemonic overlap remained. We both recalled Saturday afternoons spent amid the mock-Moorish-palace splendor of the RKO Keith’s, where I viewed Roger Corman opuses like Attack of the Crab Monsters and Liu saw his first movie. “Star Wars!” the comptroller exclaimed with a jolt of nostalgia. There were also shared memories of interminable jaunts back from “the City” on the 7 train to Main Street, the last stop on Liu’s daily two-and-a-half-hour round-trip to the Bronx High School of Science. We talked of freezing on street corners waiting for buses (the Q17 for me, the Q27 for Liu), and inhaling a slice or two at Gloria Pizza near 40th Road—RIP, the best, forever!

Yet even though we’d both walked these same small-townish streets and gone to the same YMCA, John Liu’s Flushing and mine are radically, cosmically disparate places. My most enduring Flushing memory is standing at the then-desolate corner of Main and Roosevelt, a 15-year-old returned from a beatnik-wannabe Friday night in the Village, peering into the steamy window of the Main Street Tavern. Visible within was a carving fork jammed into a giant roast beef and a couple of middle-aged drunks at the dimly lit bar. It was a future to avoid at all costs. When John Liu came here in 1972 from Taiwan (making him forever MIT, or “made in Taiwan,” as opposed to FOB, “fresh off boat,” from the mainland and Hong Kong, or ABC, “American-born Chinese”), Flushing was his future.

It was a newer Flushing, where the ever-thickening signage was in Chinese and Korean and the formerly dowdy intersection of Main and Roosevelt was getting more foot traffic than any stretch of New York sidewalk outside Manhattan, that would nurture and empower John Liu. It was here that a onetime PricewaterhouseCoopers actuary would be elected the first Asian-American to serve in the New York City Council and, later, become the first Asian-American to hold citywide office.

Asked how it felt to be a sort of Asian-American Jackie Robinson, Liu, attired in a casual pullover (it was a Saturday morning; otherwise it’s a suit and tie), laughed. “Believe me,” the comptroller said in his genial, matter-of-fact tenor. “It isn’t lost on me, the incredible opportunity and the even greater obligation of being the first. The pressure is always there. I understand the stakes, the risks of being who I am.”

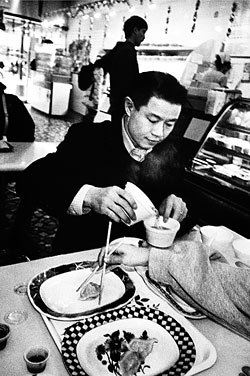

It was those risks that Liu and I had convened to discuss that January morning at the Gu-Shine Taiwanese Restaurant on 39th Avenue. This was because, along with his other firsts, Liu was the first Asian-American citywide officeholder to have a campaign fund-raiser arrested by the FBI, an incident that not only threatened his long-assumed bid for higher office but also could eventually get him indicted on federal charges.

To fill in: After persistent whispers over the summer regarding possible problems with Liu’s Campaign Finance Board filings (he raised more than a million dollars but listed zero intermediaries, or “bundlers,” responsible for aggregating the money), on October 12, 2011, the Times ran a front-page story asserting that a number of Liu’s supposed donors either could not be found or said they hadn’t given money to the campaign. Authorities believed the “straw” donors were part of a larger scheme to circumvent the city’s campaign-finance laws, the Times piece said, adding that “many of the irregularities in Mr. Liu’s campaign account are tied to companies in the Chinese business community in Queens, where he has been hailed as a hero and his picture adorns the walls of shops and restaurants.”

Then, on November 16, a federal complaint was issued against the 46-year-old Oliver Pan, a.k.a. Xing Wu Pan. The Feds contended that Pan sought to funnel an illegal $16,000 contribution, far beyond the individual limit of $4,950, into the campaign war chest of an individual identified only as “the candidate.” To cover his tracks, Pan told a would-be contributor, who turned out to be an FBI undercover agent, that he (Pan) would recruit twenty phony donors to claim they had given the campaign $800 apiece—eight being a Chinese lucky number. According to the complaint against him, Oliver Pan told the undercover that his $16,000 would buy, among other things, a meeting with the candidate at which a number of the fake donors would be present. The extra people were necessary, Pan is quoted as saying, because if there was no one there except Pan, the contributor, and the candidate, “it don’t look good.”

Not good at all, especially since the real kicker in this were alleged violations of the city’s matching-campaign-funds program, which provides $6 for every dollar of the first $175 of each donation, i.e., $1,050 in free money for each of those $800 contributions. If Liu’s campaign had authorized this, it would amount to stealing from city taxpayers. If the allegations were true and Liu had been unaware of the scheme, it still looked bad. He was the comptroller, after all.

Back in January, asked if he was worried about the allegations, Liu looked up from his noodle soup and smiled. He has a serene, supple smile. “I am cooperating fully with the investigation, wherever it leads,” Liu said. Were mistakes made in his campaign filings? Certainly, he said: He should have listed his intermediaries, but now that was being taken care of. Any questionable funds would be returned immediately. Beyond that, he was not overly fixated on what would happen. He was “a humble mathematical physics major,” a trained actuary. He dealt with the numbers, “things that I see right in front of me. I don’t tend to speculate on what may or may not happen.”

So there were no sleepless nights, he wasn’t maniacally tearing down cubicle walls in his office searching for government bugs, as the tabloids were saying? Liu shook his head and offered another smile. His conscience was clear, he said, “because I always knew my campaign finances would be scrutinized. Fund-raising efforts in the Asian community have often been closely scrutinized and questioned. We knew we had to be very careful, to look over every credit-card slip, every check. I am confident we did that to the best of our ability. So I am not worried. Not at all.”

Liu stopped and swirled his spoon through his soup and offered this caveat: “This is not to say I believe our system of justice is perfect.”

That was John Liu’s story back in January, when there was every reason to hope that he was telling the truth, or close enough to it. This was because John Liu’s story is that same old New York story we never tire of hearing about ourselves, preferably with swelling Aaron Copland music and the Statue of Liberty in the background. Liu’s family were “pioneers,” part of the initial wave of Taiwanese to come to Queens following the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which swept away the last vestiges of the neo-genocidal Chinese exclusion acts that once effectively prohibited Chinese women from entering the country. The Lius settled in Flushing, in part, because Manhattan’s Chinatown was viewed as a packed tenement pile, devoid of grasslands and terrorized by youth gangs. Chinatown was also controlled politically and economically by a Cantonese-speaking Old Guard with strong ties to Chiang Kai-shek’s mostly despised Kuomintang. In comparison, Flushing, which had maybe a couple of chop-suey restaurants, was wide open, a veritable golden mountain of opportunity, and low rents, with access to the 7 train. With people like me moving out, there was plenty of room to build another, better life.

After all, is it not a key article of faith here in the roiling melting pot: that new groups will set up shop in whatever concrete backwater; bide their time; and then, through persistence, savvy, and the accumulating force of numbers, make their move toward a seat at the table of power? John Liu, son of Asian-American Flushing, product of luck, pluck, parental expectation, and the public-school system, is firmly in that tradition, stitched into the same however unkempt quilt of New York ethnic politics that includes Paul O’Dwyer, Fiorello La Guardia, Ed Koch, Adam Clayton Powell, Herman Badillo, and thousands more.

What’s different about John Liu is that he’s the first major politician to come from what one CUNY professor calls “the new demographic”—the umbrella term for the millions who have arrived in New York since the 1965 law change, a now near-50-year migration that has reconfigured the entire country, not just New York. Try this factoid on for size: We currently live in a city where just a bit less than 40 percent of the people are foreign-born.

One reason these seismic changes haven’t yet been felt in the political realm is that the city has been living through a period of political suspended animation since 9/11 and the election of Mike Bloomberg, who, nasal whine aside, belongs to a cultural taxonomy unto himself, one that transcends (or simply buys out) quaint distinctions like where you’re from, what you eat, what leg you kick with. But now that Bloomberg is finally about to bite the Big Bermuda, what potential mayoral candidate Bill de Blasio calls “the new identity politics” is back on the front burner. New numbers, new coalitions will come into play. In the forefront of this arithmetic is the Asian-American community, the city’s fastest-growing demographic. Once politically invisible, New York’s Asian population has increased 32 percent in the past decade to just over a million, half living in Queens. Nowadays, no serious pol can afford not to show his face on Chinese New Year’s. So it makes sense that an exceedingly ambitious politician like John Liu, a man with a talent for assembling cross-ethnic coalitions, might consider this to be the time to make his move—and indeed, Liu was a strong contender to be the next mayor.

That was until the Oliver Pan story broke. Long regarded as a cheerful, attention-seeking motormouth, Liu found his press image had gone seriously south. In the 119 days between the October 12 Times piece to February 8, the New York Post, never fond of the comptroller’s extensive union ties and progressive political positions, ran 54 pieces dwelling on the finance scandal or otherwise portraying the “embattled” Liu in an unflattering light. Even Cindy Adams bashed him. The Daily News was hardly more favorable. One piece that raised eyebrows was a January 10 Times story, played on the front page, detailing how Liu had given out an inordinate number of commendations to various church and business groups—a pretty standard political practice.

The barrage engendered push-back, as Liu’s union and outer-borough minority base rallied behind him. He received standing ovations at venues all over town, including Al Sharpton’s House of Justice and a LGBT forum. Council member and prospective candidate for public advocate Tish James said, “John Liu has been saying things that have scared some people. This is a blatant attempt by the permanent and invisible powers-that-be to bring John down.”

Conspiracy theories flowered. Someone was out to get Liu, and it wasn’t hard for many to point a finger at who that might be. “Bloomberg hates Liu,” said one well-known former Queens-based elected official. “Bloomberg doesn’t like to be audited, you know. That CityTime thing was a disaster, and Liu has milked it for all it is worth.”

The CityTime thing is a scandal that, if it hadn’t been so mysteriously underreported, might by now have taken its place beside the Parking Violations Bureau corruption case that ravaged Ed Koch’s third term, minus the knife in the ample breast of Queens borough president Donald Manes. When the CityTime project (aimed at automating the city’s payroll, among other things) first began in 1998 under the Giuliani administration, the cost was projected at $63 million. Thirteen years later, by the time Liu became comptroller, the city had already spent as much as $760 million, the lion’s share going to outside consultants. Liu made it an issue, declaring himself “absolutely shocked to find this sort of waste and mismanagement at a time when the mayor is talking about closing schools and firehouses.”

“That sort of stuff pisses Mike off, especially if he thought Liu was using the comptroller’s office as a cudgel to run for mayor, which he has been doing since the day he got into office,” asserted the Queens pol, repeating the oft-heard charge that Bloomberg, who everyone assumes will support Christine Quinn in 2013, “uses his chairmanship of the Billionaire’s Club to influence coverage in the three daily papers.”

A more anguished form of push-back came from the Asian-American community. After all, for better or worse, John Liu is their guy, the first one across the line. No other Asian-American politician even vaguely approaches Liu in stature, experience, or easy crossover grace in front of a TV camera. The guy is just so damn friendly, so obviously pleased as punch when people recognize him and shake his hand. Even as the bad stories in the papers piled up, Liu continued to attend multiple events a day, continued to speak as if running for mayor. He seemed unstoppable, unflappable. Grace Meng, the Flushing Democrat who holds the State Assembly seat first won by her father, Jimmy Meng (the first Asian-American to do that), has had her differences with Liu in the past but says, “If anything happens to John, that could be difficult for us.” Virginia Kee, the longtime downtown political figure, went as far as likening Liu’s troubles to those of the Chinatown-born Danny Chen, the U.S. Army private who is thought to have committed suicide following a series of alleged hazing incidents by fellow servicemen in Afghanistan.

Beyond this is the overwhelming, unshakable attitude on the part of many that Liu is being singled out for no other reason than he is Asian. Uppity and Asian. Feelings in the Chinese community were more or less summed up by an elderly man named Chu, whom I encountered at a Year of the Dragon banquet held at the massive Jing Fong restaurant. Becoming a citizen after nearly 25 years of living in and around Flushing, Chu had never voted until casting his ballot for John Liu in 2003. He said, “When Chinese people first come here, they make us work on the railroad. That’s what they do to John Liu. Railroad him!”

At least this was the way it seemed back in January, before the FBI arrested Liu’s 25-year-old campaign treasurer, Jia “Jenny” Hou, last week on fraud and obstruction-of-justice charges. According to the 24-page federal complaint, Hou coached a campaign worker to imitate the handwriting of donors, offered to personally reimburse a donor for a contribution, and collected fraudulent forms from “straw donors” while in the employ of an individual identified only as “the candidate.”

This served to alter the tenor of the Liu narrative significantly. After all, Jenny Hou was no Oliver Pan. According to many in Chinatown, Oliver Pan was one of “those Fukienese guys from East Broadway” who’d “show up at local political functions, check it out to see if there was any action, and leave.” Jenny Hou was a Flushing resident, a Rutgers graduate, daughter of a longtime Liu supporter, with dozens of happy pictures on her Facebook page. Born in Beijing, a Mandarin speaker, Jenny Hou was a bright young New Yorker with her whole future in front of her. Now, because she worked for John Liu, the Feds said she was looking at up to 60 years in jail.

People say that if you want to figure out who John Liu really is, you have to go back to the day his father Americanized the family’s first names. “Dad was a Kennedy fan. So when we came here, he changed his name to Joseph. He had three boys, so I became John and my two brothers Robert and Edward,” Liu said, adding that when his own son was born, he was named Joey, which “broke the tradition.”

“The Taiwanese tradition?” I inquired dimly.

“No,” Liu replied. “The Kennedy tradition … you’re supposed to name the first boy after the father, which would have made Joey named John Jr., but we decided not to follow that and name him after my dad.”

This was interesting, because as much time as I spent with John Liu, attending his blizzard of public events, listening to his near-Asbergerian explanations of his plan for city pension reform, laughing at his jokes (asked what exactly an actuary does, Liu replied, “It is kind of like being an accountant minus the personality”), there was only one thing the comptroller seemed to absolutely, positively want me to hear and understand. This involved his father, patriarch of his Flushing-bred Kennedy clan.

It is a story that Liu tells with a gathering intensity. “My father had the good fortune of being the second son, so he got to go to college. His older brother stayed behind to tend the farm. That is how it was in Taiwan. How it always was. We have a family temple with the family tree inside. I am like the twentieth generation, which is a very long time.

“Anyway, my dad is a smart guy. He went to National Taiwan University. He worked for the Bank of Taiwan for ten years. They sent him to America to get an M.B.A. He was in America for two years and came to the decision that he wanted his kids to grow up here. That’s how we came to Flushing. My father sacrificed everything, a high-flying career, because he wanted us to grow up in a better place. But now that we were here, he couldn’t get a job. He was blacklisted. No Taiwanese bank would hire him. Finally, he wound up at a Japanese bank in a dead-end position. A clerk! So when he got the chance to be part of a bank in Flushing, he took it.”

Liu’s narrative breaks off here, but the public record is fairly straightforward on what happened next. In 1984, with Flushing already well on its way to becoming an immigrant boomtown, Joseph Liu and a number of partners formed the Seven Giants Properties to develop a Main Street property intended to serve as the headquarters of the Great Eastern Bank. According to a 1999 federal indictment, the Great Eastern directors, of whom Joseph Liu was one, approved a 30-year lease between the bank and Seven Giants that included a $1 million payment to the company. This amounted to a misapplication of bank funds, a move prosecutors contended the group covered up with false entries in books and records. Liu was later convicted on bank-fraud charges.

On January 8, 2002, less than two weeks after his son was inaugurated as the first Asian-American city councilman, the then-65-year-old Joseph Liu was sentenced to a month in jail, with six additional months of home confinement. John Liu, who turned 35 that day, attended the sentencing. Interviewed by the Daily News, Liu said that “[there’s] no one more honest, no one more forthright” than his father. He later told the paper, “The verdict was completely wrong.”

As it would turn out, Joseph Liu’s problems would help his son’s career. “It really impressed me, the way he handled the stuff about his dad,” said one Chinatown resident. “For a lot of older Chinese people, that would be the end, something like that in your family. But Liu said, ‘I will always love my dad no matter what. But I am not my dad. I stand on my own two feet.’ It struck me as a modern thing, a brave thing, for a Chinese-American to say.”

Ten years later, Liu is still adamant that his father was unfairly convicted. Throughout his current troubles, Liu exuded an eerie sense of invincibility, as if none of this were really happening to him. But reliving his father’s case had him visibly upset.

“I’ve always felt guilty about what happened to my father,” Liu said, suddenly choked up. “Because sometimes I think if I hadn’t run for office, if I wasn’t in the public eye, perhaps my father would never even have been targeted … Anyhow, when I tell you that our system of justice is not perfect, this is what I mean.”

Given all he’d just told me, did Liu think his current situation might be a case of history repeating itself?

Back in his Vulcan/Spock manner, Liu said, “What you’re asking me requires a degree of uncertainty. That’s not to say I wouldn’t analyze the cause and effect if I had a basis for thinking that cause and effect had a high probability of explaining anything … but I don’t see that right now.”

Every New York immigrant experience becomes epic once you begin to fill in the thorny details. In 1997, when the then-30-year-old John Liu first ran for City Council, his opponent was Julia Harrison, a 77-year-old Flushing Olde Tymer and Queens County Democratic stalwart. Harrison had caused a stir by characterizing her new Asian neighbors as part of an “invasion,” more like “colonizers than immigrants,” people whose money always preceded them, followed by “the paupers … smuggled in and bilked by their own kind.” There were so many Chinese signs in Flushing, Harrison said, that her constituents couldn’t tell a “hairdresser” from a “nail salon” from a “whorehouse.” This was not in keeping with the spirit of the Flushing Remonstrance, the 1657 declaration of religious tolerance, but Harrison wasn’t the only who felt that way. She crushed Liu in the ’97 primary, but that was the Olde Tymer’s last stand. Four years later (with Harrison term-limited), when Liu narrowly beat two other Asian-Americans, the result seemed inevitable.

In the ten years since Liu’s election, Flushing has become a wholly different place again. The former Taiwanese village set down on the stinky edge of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby ash pits has morphed into a more rough-and-tumble global marketplace. The Taiwanese presence has been diminished these days. Huge developments like the $820 million, mixed-use Flushing Commons will soon rise on the site of the municipal parking lot bordering Union Street. The old RKO Keith’s building, shuttered since the middle eighties and a community flash point since cowboy Taiwanese-born developer Tommy Huang attempted to replace it with a shopping center (the basement got flooded with heating oil, turning the place where many had gotten their first kiss into a toxic-waste dump), is also expected to finally be developed. With a new international hotel planned, Flushing has become, in the words of former Queens borough president Claire Shulman, “a crossroads of the world.”

The changes are such that John Liu, the local hero, thinks he soon might “not even be able to recognize” the place where he grew up and still lives. Already, he found it hard to converse with a large percentage of his Flushing constituency, much of which now consists of recently arrived immigrants from the Chinese mainland. This owes to the fact that, like many of his generation, John Liu can barely speak Chinese. “We left Taiwan when I was 5, so I always say my Mandarin is like that of a 5-year-old.” Asked if he regretted not continuing with his Chinese, Liu said, “I regret it every day. But when I was a kid, the idea was that the key to success was the English language. This is obviously not the case today. There are 800 million people in the world speaking English and a billion and a half speaking Chinese. So, for all practical purposes of getting ahead in the world, it is better to speak Chinese. My son, Joey, sounds like a New York kid, but he understands the importance of speaking Chinese.”

Liu chalks these shifts up to “the ever-changing dynamic of New York, where everything is always in transition.” It is the immigrant’s lot, Liu said, “to always be somewhere in the middle.” The danger was that “things tend to be lost in the translation.”

It was something to think about while moving around the old hometown, because truth be told, these last weeks, I was beginning to seriously wonder about my Flushing homie John Liu. The Feds’ legal net was tightening around him. The conventional wisdom (and many blind quotes in the papers) indicated that Jenny Hou would eventually flip, telling everything she knew, fatally implicating “the candidate.” Yet Liu continued to schedule events, insist that he was moving ahead, keeping his mayoral options open. Was there some cultural nuance I was missing?

Such miscommunications may have gotten Liu in trouble before, most notably in the 2009 comptroller race, when his campaign ran a web commercial featuring the candidate’s story of how, when his family first came to Flushing, his mother had no choice but to work in a “sweatshop” sewing garments. When Liu’s mother disputed this account to a Daily News reporter, the story blew up. After all, how could you trust a guy to keep an eye on a $120 billion pension fund when his own mother was calling him a liar in the newspaper?

Queried about the incident, Liu gave a defense that is both cultural and personal. “I never knew until that moment how awful my father felt about my mother having to work, much less in a sweatshop,” the comptroller said. “Back in Taipei, she had three housekeepers. Now, after my dad brought us here, she is working in a sweatshop and bringing me along. When the reporter asked about the sweatshop, my mom tried to protect my father, the shame he felt.”

Nonetheless, this was how a number of people, Asian and otherwise, felt about Liu’s current predicament: It was a cultural thing. Much of this has to do with money, or at least the perception of the Chinese attitude toward money. In the late nineties, after my father died, my mother decided to sell our Flushing house. My parents had purchased the place for $12,000 with the help of a G.I. loan in the early fifties. But this was a whole new world, the real-estate lady told my mother. The place was worth at least $300,000, maybe more if the buyer turned out to be a stooped-over Chinese guy who got out of his dented Toyota holding a suitcase stuffed with cash.

“Sounds typical,” said Jeff Yang, who writes the “Tao Jones” column for The Wall Street Journal and once edited a book called Secret Identities: The Asian-American Superhero Anthology. “In the West, we tend to think about money in the abstract—what does my money and what I do with it say about me? The Chinese attitude was more straightforward. Money equals power, that’s it,” Yang said. For the immigrant, cash mattered, because “they can’t speak the language, they can’t vote. Yet they need some control, some power over their surroundings. That power is cash, and the transfer of it is simple, direct. If a John Liu comes along, he’s the comptroller, a successful and powerful man with an even better future. So people want to connect with him in the best way they can. They want to give him their money. It doesn’t matter how rich they are, if they’re broke, or what some convoluted law they never heard of says: It is an honor to give money to John Liu.”

Indeed, as several Chinatown friends pointed out, the details in the original Times “straw donor” story bore a strong similarity to another article published in 2007 by the Los Angeles Times concerning Hillary Clinton’s presidential-primary run. Much as the New York Times reporters would four years later in their Liu story, the L.A. Times writers described visiting various East Broadway haunts seeking Fukienese kitchen workers whose names had appeared as Hillary donors but now were nowhere to be found. Another constant in the two incidents was the presence of Chung Seto, the 46-year-old longtime Chinatown resident and former executive director of the New York State Democratic Committee, who helped run Hillary’s local fund-raising drive, a task she has performed for John Liu for much of the past half-decade. Asked why, if he was so concerned about scrutiny of Asian donors, he would retain someone like Seto (who also served as the manager of C. Virginia Fields’s mayoral run in 2005, in which campaign-finance issues also surfaced) to oversee his effort, Liu said only that “Chung is a brilliant woman. I trust her completely.”

At any rate, for many in the Asian-American community, what was happening didn’t seem to have much to do with whether John Liu and his campaign followed the rules. Said a Mott Street businessman friend, “This whole campaign-finance thing is bullshit. No one cares. What matters is China. The Chinese and their money. The Chinese own our debt, they can buy and sell us. That’s the fear. Yellow peril, the sequel. You think the U.S. government isn’t interested in how Chinese money comes into this country, who gets it, where it goes? That’s the essence of the John Liu thing, if you ask me. It is a message. It says, ‘We’re watching.’ ”

This was what it came down to, people said: Sure, it was nice that someone like John Liu, who jokes that “both my first and last names mean toilet, and I’m from Flushing, so don’t even talk to me about my destiny,” was the first Asian-American to hold citywide office. But in the bigger picture, Liu occupied a potentially far loftier position. A Chinese guy in charge of the money. According to this scenario, there were hundreds of mainland businessmen in New York, party-member owners of tool-and-die factories from Xi’an, Zhengzhou, and Fuzhou, just desperate to have their picture taken with John Liu, to show how connected they were in the City of Jeremy Lin.

Hearing this while standing on the sidewalk in front of the 109th Precinct on Union Street, John Liu exhibited a pained look. “Everywhere I go, people want to take a picture with me,” he said, barely able to keep his reporter-friendly face on. The fact was Liu was sick of hearing about the FBI and the darkening cloud supposedly hanging over him. All he wanted to do was do his job, he said, serve the city he loved. On that day, he was in the middle of preparing what he called a State of the City speech that would detail all the money his office had retained for the municipality over the past two years in the categories of “cost savings, revenue enhancements, and cost avoidance.” The grand total for 2010 and 2011 was $923,997,028, or approximately 58,000 times the $16,000 Oliver Pan supposedly collected from the FBI undercover.

But what did that matter? What did it matter that Mitt Romney just got a quarter of a million dollars from a company giving its address as a post-office box, or that vampires like Gingrich were being fed with scraps off a Vegas blackjack table? They could do what they wanted in China, but here the law was the law, and if Liu’s campaign broke the law, as captain of the ship, he would have to go down. It didn’t matter if the comptroller knew what was going on or not. At the very least, he was guilty of a stupefying degree of willful obliviousness.

This entire episode was starting to feel very sad. It was sad because no one wants to see Jackie Robinson strike out. No one really even wants to see David Dinkins strike out. Even the people who hated Liu, those who’d run campaigns against him and thought him to be, as one operative said, “a guy with a Messiah complex who lied about his personal narrative, who will say and do anything, including extensive playing of the race card, to get ahead,” said the Liu incident was a potential “tragedy in the making,” bad for the Asian-American community, bad for the ideal of the city.

Peter Tu is the executive director of the Flushing Chinese Business Association. A short barrel of a man in his late fifties, Tu arrived in Flushing from Taiwan more than 30 years ago and has seen “it all.” When I reached him, Tu was in the middle of planning Flushing’s upcoming lunar New Year’s Parade.

Asked about John Liu, Tu grunted. The Liu thing was a “big problem for me!” Tu exclaimed. “When we first hear about it, all my members are calling me, day and night, the phone is ringing. Everybody is upset. They don’t know what to do. We have pride in him. He wants to run for mayor, so people give him $800. It is the right thing to do. Then, the next day, the FBI is at the door with a subpoena. Eight hundred dollars becomes $10,000 in lawyer fees! That is bad business! I have to tell my members, if you don’t want the FBI at your door, don’t give a first penny to John Liu. Wait a minute or two. See what happens.”

It was too bad, Tu said, because “John Liu is the smartest, most qualified, hardest-working politician we ever have in this community.” But the comptroller had a potentially fatal flaw. By being “too aggressive,” Liu had lost sight of “his Chinese nature.” It had nothing to do with failing to act more like the stereotypical retiring, timid Oriental. On the contrary. New York ethnic politics was “a big fight.” To come out on top was a matter of strategy, tactics, practicality, Tu said, rising from his desk as if to act out a Flushing version of Sun Tzu’s Art of War. Liu’s big mistake was forgetting he was “a minority,” an arrogance that blinded him to the fundamental principle of knowing “when to attack, when to give space.” What was the point of going up against Bloomberg when the mayor still had all the power? Why would someone want to poke a finger into the eye of the FBI? “It makes no sense,” Peter Tu said.

This said, Tu hoped that Liu would survive and live to fulfill his potential. But what if he didn’t, what if Liu went down?

“Then we will learn from him,” Peter Tu said.

It had been a particularly heavy year for lunar New Year’s parades around the city, owing to the especially fecund place the dragon holds in the twelve-year cycle of the Chinese zodiac. Of all the celebrations, the biggest took place in Manhattan’s Chinatown. In the seventies, New Year’s in Chinatown was a more surreptitious, dangerous event. It was important to map routes so drummers and lion dancers from 9-mm.-packing Ghost Shadow and Flying Dragon gangs did not run into each other. Now the parade is sponsored by Verizon and MetLife, with most of the extra noise coming from tubular party poppers filled with confetti.

Walking at the front of the parade, Liu drew robust cheers on Mott Street, but it wasn’t until the parade crossed Chatham Square and turned onto East Broadway, where the bulk of the recently arrived Fukienese immigrants live, that the scene went electric. Four and five rows deep behind the police barriers, the East Broadway people surged toward Liu, shouting his name, reaching out to touch his arm, pat him on the back. Energized by the adulation, Liu plowed through the crowd, shaking as many hands as he could. To recall Joseph Liu’s particular version of the American Dream, the reception could only be called Kennedyesque. It mattered little that neither Liu nor the large majority of the crowd could speak to each other. What counted was the fact that Liu looked like them. He was their guy, the one anointed to carry forth their hopes and dreams. When the comptroller wrote on a long red banner, the only name out of hundreds to be signed in English, a great cheer went up.

A week later, the annual Flushing parade, led by Peter Tu with his red Grand Marshal sash across his chest, had a more laid-back feel. Only the day before Liu had told me, “Some have mentioned that no matter what happens, I will come out of this painted as an ethnic candidate as opposed to a New York candidate. It is what Asian-American academics call ‘the perpetual foreigner syndrome’ … that it will always be hard for Asians to be accepted as real Americans. This not helpful. Because that’s not who I am.” Now, however, walking with his wife Jenny and son Joey, Liu seemed relaxed. “After all,” he said, “I’ve been coming to this parade all my life.” As the procession moved toward Queens Crossing, the Singapore-style office building where most of Flushing’s global heavies keep a presence, the “Money God” came out. A typically more direct version of Santa Claus, the Money God appears every year in his long black beard and headdress, carrying little red envelopes stuffed with cash or candies, which he gives to children. From across the street, I watched a man dressed as the Money God stop to say something to John Liu. Later I asked the Money God, who turned out to be a middle-aged Flushing resident, what he’d told the comptroller.

“I told him good luck,” the Money God said. “ ‘Good luck, John Liu!’ Because he is going to need it.”