This story was originally published on May 27, 2011. On July 13, 2023, a local architect, Rex Heuermann, was arrested as a suspect in the Gilgo Beach killings.

Short and slight, with an off-kilter smile and wide anime eyes, Shannan Gilbert had drifted into escort work when she was about 20 as a way to earn money while trying to make it as a singer. That night at Oak Beach, she was wearing a blonde wig, a pair of dangly hoop earrings, a brown leather jacket, and jeans. On nights like this, she’d tell her boyfriend she was going out on auditions.

The oldest of Mari Gilbert’s four daughters, Shannan finished high school in New Paltz at age 16. “She wasn’t street-smart, but she was book-smart,” Mari says. Shannan had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder but stopped taking her medication, complaining that it gave her the shakes. After graduating, she worked at a hotel, an Applebee’s, and a senior center, but by 2007, she had moved to New Jersey with a boyfriend and signed on with an escort agency. She had at least one arrest in her record, having been rounded up with some other girls from Upper Saddle River, and one time was beaten to the point where she needed a titanium plate in her jaw. Two years ago, she started posting ads for herself on Craigslist, where she could charge $200 an hour and keep two thirds of the fee; the other third went to a driver, who would take her to dates and provide security. Shannan liked to party—mostly pot, coke, and prescription drugs—but if she managed to make it through the night without burning through too much of what she earned, she could get home after five calls with $600 or more in her pocket.

The extra money had allowed Shannan to move into a place of her own for the first time, in Jersey City, and she was close to completing a series of online college classes that might have helped her stop escorting. But she liked to visit her family, take her sisters on shopping sprees, and lavish gifts on her nieces and nephews. Mari, who works at a Wal-Mart, knew where the money was coming from and searched for a way to talk about it with her daughter. “I tried to tell her ‘Don’t do it. Stop. Move back in with me,’” Mari says. But Shannan refused. “Mom,” she would say, “I hardly have to do nothing, and I get thousands of dollars.”

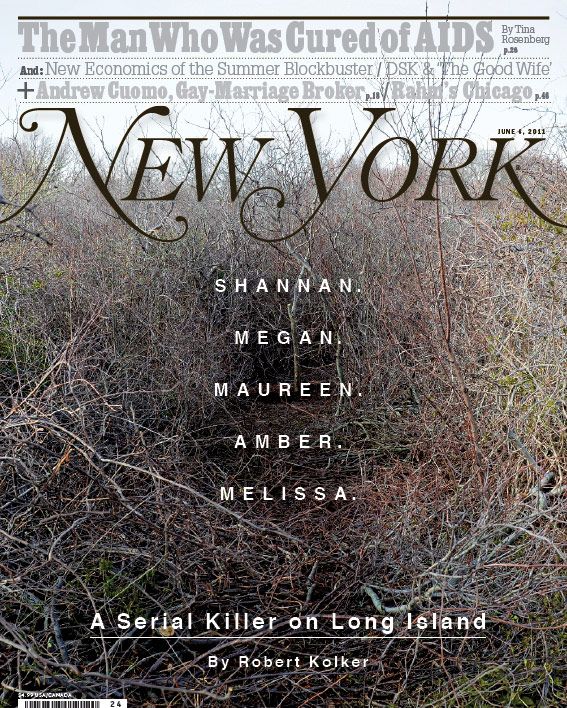

Cover Story

On May 1, 2010, at about 2 a.m., Shannan arrived in a dark SUV at a two-story wood-frame house on Fairway Drive in Oak Beach, Long Island, a quiet gated community a few miles from Fire Island, on the string of barrier islands along South Oyster Bay. The house belonged to Joseph Brewer, a 46-year-old unemployed financial adviser who was separating from his wife. A few hours earlier, Brewer had responded to an ad Shannan had posted on Craigslist. The most thorough account of what happened next comes from Michael Pak, a driver Shannan had worked with before and was working with that night. Once Pak dropped off Shannan at Brewer’s house, he says, he waited in the SUV, playing poker on his cell phone, while Shannan and Brewer were together. Another source reportedly saw the two leave the house once, in Brewer’s car, for about fifteen minutes. It’s not clear where they might have been going, although Pak says it wouldn’t have been unusual if Shannan were looking for drugs. At about 5 a.m., Pak says, Brewer came out of the house and asked him for help.

Inside, Pak says, he found Shannan in a panic, clutching her cell phone. Police records would later show that Shannan had called 911 from that phone at 4:51 a.m. and kept the dispatcher on the line for 23 minutes. On the 911 recording, she sounds frantic; voices in the background can be heard trying to calm her down (if the police know who they are, they aren’t saying). Shannan never told the 911 dispatcher where she was—it’s possible she didn’t know, having been driven there—so the police had no way of sending help. Pak says he tried to get Shannan to leave with him, but she refused to go. She seemed delirious; he thought it might be drugs. Pak left the house, frustrated. He got back into the SUV and waited.

A minute or two later, Pak says, Shannan bolted from the house, stumbled down the front steps, and took off down the road. Pak says he followed her in the SUV, but she kept running, screaming for help. A neighbor, 75-year-old Gustav Coletti, was up early, shaving, when he heard a pounding at his door. When he opened it, he says, Shannan ran inside, shrieking that her life was in danger. Coletti says he told Shannan he’d call the police. But for reasons that remain unclear—had someone threatened to harm her if she called the cops? Was she afraid she’d get arrested?—Shannan begged Coletti not to make the call.

Coletti says Shannan ran out of his house and out of sight. By the time Pak pulled up, Shannan was gone. Pak says he spent close to an hour driving around Oak Beach searching for Shannan before giving up and heading back to the city. As the sun rose and the police finally arrived, 45 minutes after Coletti had called them, the only trace of Shannan Gilbert was a set of footprints in the sand, heading in the general direction of an empty, overlooked stretch of shore called Gilgo Beach.

The Suffolk County police searched Joseph Brewer’s house, seized his car, questioned him and Pak, and concluded that neither was a suspect. (Brewer and Pak say they’ve been polygraphed; the police won’t comment. Brewer would later insist to reporters that he didn’t even sleep with Shannan and that he just wanted company. He said he saw no drugs.) Police searched the area and found nothing. Coletti was cleared as well. By fall, it appeared all leads had dried up.

Then, on December 11, just before the first snow of the season, a Suffolk County detective with a cadaver dog was on a training exercise on the side of the road in Gilgo Beach, three miles from Brewer’s house, when the dog turned up a set of bones. The remains were not Shannan’s—there was no titanium in the jaw. But when the police searched again two days later, they found three more sets of bones. The four bodies—just skeletons with no clothing or jewelry, all of them wrapped in burlap—had been left roughly 500 feet apart from one another. They also were all deposited at exactly the same distance, 50 feet, from the edge of Ocean Parkway. Investigators suspected the victims had been strangled. On December 14, the Suffolk County police announced they were looking for a serial killer.

Shannan Gilbert still hasn’t been found, but her profile matches almost exactly that of the four women whose remains have been positively identified. Shannan, Maureen Brainard-Barnes, Melissa Barthelemy, Megan Waterman, and Amber Lynn Costello were all $200-an-hour escorts in their twenties, all but one of them five feet tall or shorter, who advertised online on Craigslist or similar websites. “My case linked them all together,” Mari tells me. “Without Shannan, there’d never be a case.” And while it seems clear that Shannan is a victim of the same killer, some small part of Mari would like to think her daughter is still alive.

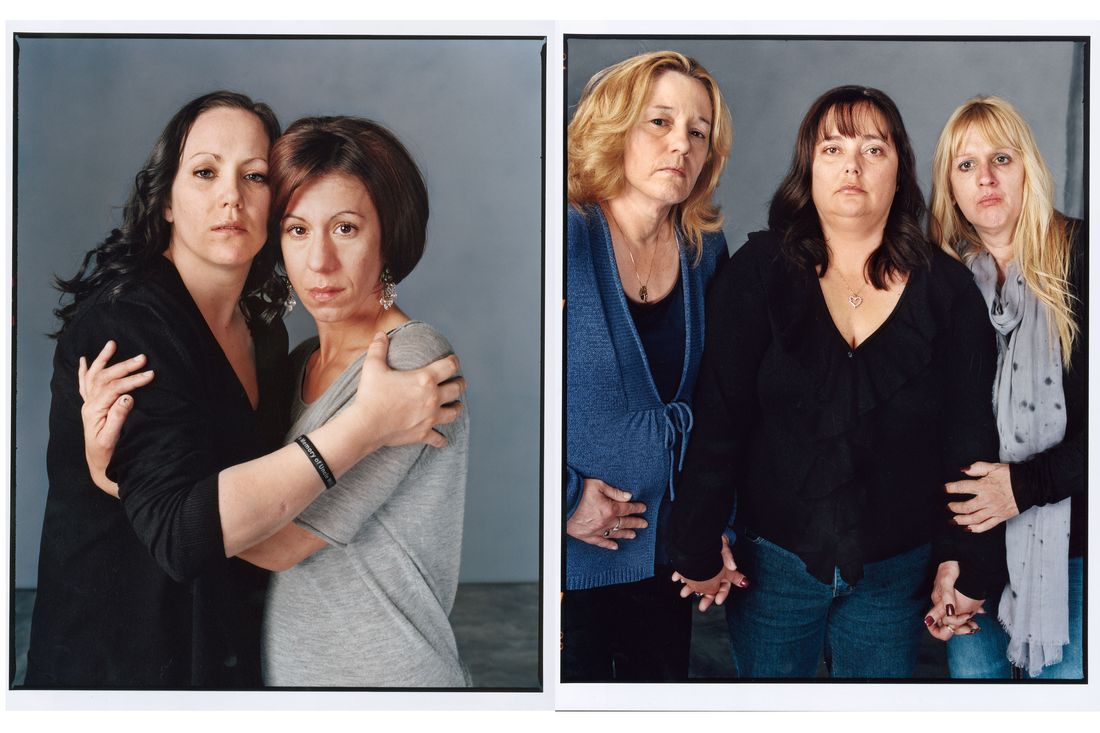

On Monday, May 2, a year and a day after Shannan disappeared, Mari Gilbert and four other women came together in Manhattan to meet, at my invitation. Until that day, the five women had been in touch only through Facebook or by phone; just two of the five had seen one another in person. In addition to Mari, there was Megan Waterman’s mother, Lorraine Ela; Amber Costello’s sister, Kimberly Overstreet; Melissa Barthelemy’s mother, Lynn; and Maureen Brainard-Barnes’s sister, Melissa Cann. The group makes up a kind of grim sorority: They are the sisters and mothers of those who appear to have been the victims of the most skillful and accomplished serial killer in New York since Joel Rifkin or David Berkowitz, the “Son of Sam.”

We met at a Tribeca hotel for breakfast. Ela had flown in from her home in Maine, carrying a laptop filled with pictures of her daughter. Overstreet left her father’s hospital bed in North Carolina to make the trip. Barthelemy shut down the diner she runs in Buffalo; she also brought along her longtime fiancé, Jeff Marina, and her teenage daughter, Amanda. Cann, who was tense about traveling alone to the city from which her sister disappeared, coaxed her husband, Chris, into driving her and three of her children in from northern Connecticut after he’d worked the night shift at his job on a military base.

Mari Gilbert has the same eyes and smile as Shannan, only with long, straight blonde hair and a raspy, lived-in voice. At first, Mari felt somewhat ill at ease. “I’m different, in a way,” she said. “Shannan is still missing. She’s not a body.” But the others welcomed her. They are bonded by grief, confusion, guilt, and anger. Could they have done more to help the women stay out of trouble? Would the police have caught the killer by now if the girls weren’t prostitutes? Who were their sisters and daughters, really?

Maureen Brainard-Barnes was the first of the girls to disappear; she went missing on July 9, 2007, three years before Shannan Gilbert. Maureen grew up in Groton, Connecticut, a blue-collar town where the biggest employers are now the Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun casinos. Maureen filled composition books with poetry and song lyrics. She wasn’t interested in material things and didn’t wear makeup. In high school, she’d been a straight-A student, but she dropped out at 17 when she got pregnant. She married, got her GED, then divorced, sharing custody of her daughter, who is now 11. Maureen worked as a blackjack dealer at Foxwoods, at a ShopRite, and at a gas station. Sometime in 2006, she saw a you-can-be-a-model offer on the web and sent in pictures of herself; a friend she made in the process introduced her to escorting on Craigslist. Maureen started taking weekend trips into Manhattan, telling anyone who asked that she was going on modeling gigs. Early on, she became pregnant again with a boyfriend and briefly gave up escorting. But once the second baby arrived, she started again.

Most of Maureen’s friends and family knew what she was doing in New York. “We all had a kind of idea about it, but we didn’t want to actually think of it,” says her sister, Melissa Cann. “No one could keep Maureen from doing something she wanted to do.” While in New York, Maureen would call friends on her cell phone, sometimes just to chat, other times asking them to refresh her Craigslist ad so it would be at the top of the page again. A friend says much of what she made would go to pot and cocaine.

The weekend she disappeared, Maureen had taken the train into the city with friends, but she left them once she got to Manhattan. Cann says her sister usually worked from a hotel room and never saw johns at their places. Maureen was adamant about working only in Manhattan and never said anything to Cann about working in Long Island. At one point that weekend, Maureen called a friend from the Port Authority and said she’d been robbed of all the money she’d earned. She needed a ride home, but the friend couldn’t come get her. After that call, no one heard from Maureen again. For three years, the NYPD had reported no trace of her—except, in 2008, for one cell-phone-signal ping off a Long Island tower, just a few miles from Gilgo Beach. “Someone was trying to access Maureen’s cell-phone voice-mail,” Cann says. When she saw the news about Gilgo Beach, Cann knew Maureen had to be one of the bodies.

Cann was the first to reach out to another family on Facebook, and since February she’s been orchestrating contact with at least a half-dozen relatives of the five victims. I visited her near her home in Groton in April. Fair and winsome with jet-black hair, she talks in a fragile voice about the children Maureen left behind—the 11-year-old girl by one father whom Cann sees on weekends and the 5-year-old boy by another who now lives with his father.

Cann says the police have failed to take her sister’s case seriously, beginning with the first officer she spoke to. “Soon as I told him what she was doing up in Manhattan, it was like he didn’t care.” She speaks of the fruitless trips her husband and brother took to New York to try to find Maureen themselves, the two and a half years it took even to get Maureen’s name onto the national registry of missing persons. She tells me she got her sister’s e-mails, texts, and phone records herself, trying to retrace Maureen’s steps. “I’ve been driving myself crazy for four years trying to figure out what happened to my sister,” she says. “I drove myself to the point where I didn’t want to get up in the morning to brush my teeth. I didn’t want to go to sleep. I just wanted to figure out where my sister was. I got fired from my job. I was like, I can find another job, but I can’t find another sister. Going on with my life felt guilty.”

When I ask Cann about Maureen’s life as an escort, she says her sister was desperate. “I found out after she was missing that she had eviction court the next day. It was her last resort.” Cann knows people judge her sister. “I don’t like how they’re talking about her,” she says. But to Cann, it doesn’t matter what Maureen did. “She was still a mother. She still meant the world to her daughter, and me. She was in her mid-twenties. Who’s to say that she was going to be doing this her whole life?” When she looks back on what she could have done to change Maureen’s mind, she says, “We got into arguments about things that I thought that she was doing, but I always gave in and dropped the subject. I didn’t want to push her away.”

Melissa Barthelemy disappeared two years after Maureen Brainard-Barnes, on July 12, 2009, on her way to a Craigslist appointment. She grew up in Buffalo, lived for a time with her father in Texas, then came back to Buffalo to finish high school. Melissa got a license in cosmetology, worked for a time at a Supercuts, and moved to the Bronx in 2007. “She wanted to make money for a salon of her own,” says her mother, Lynn. “And originally when she moved to New York, she was working in a salon. We think the salon was a cover for her pimp here.”

Melissa told her mother she was just dancing at a club. That was enough to worry Lynn. “I used to tell her, ‘You know, I’m not around the corner. It would take me eight hours to get to you,’” Lynn says. The last time Melissa came home to visit, Lynn says, “she was kind of down, and we almost had her convinced to stay. She was depressed because money was tight. We even told her, ‘We’ve got a job all set up for you.’” But Melissa went back to New York. She was stubborn, Lynn says. “She didn’t take crap from anybody.” Now Lynn wonders if she should have tried harder to persuade Melissa to move back home.

Lynn sees many things differently now. Going through Melissa’s belongings after she disappeared, Lynn found a letter Melissa wrote to her pimp telling him he was taking too much money and she was tired of working for him. “She once told us she was walking home at night and someone tried to steal her purse and he had a knife and she took the knife away from him and stabbed him,” Lynn says. Years later, Lynn heard the thief was a john.

Melissa’s sister Amanda had visited Melissa twice in New York and knew everything. “She didn’t really come out and say it,” she says. “But I’d hear her on the phone calls or see her posting on Craigslist.” Seven days after Melissa disappeared, the phone rang at Lynn’s home in Buffalo. The caller I.D. displayed the number of Melissa’s missing cell. Amanda picked up. The voice was self-assured. “Is this Melissa’s little sister?” he asked. “I hear you’re a half-breed.” Amanda’s father is black. Whoever was calling knew what Amanda looked like.

There were seven calls in all. Once, the caller seemed to toy with Amanda, asking if she knew what Melissa did for a living. Another time he said, “Are you gonna be a whore like your sister?” Police traced some of the calls to midtown Manhattan and another to Massapequa. In the last call, in August 2009, he told Amanda outright that he had killed Melissa. Lynn and Amanda started to worry that the caller knew where they lived. A short time later, they moved.

Megan Waterman vanished next, on June 6, 2010. Moon-faced and bubbly, Megan lived in working-class Scarborough, Maine. She had been more secretive about escorting than Shannan and Maureen; her family learned about it only when her mother, Lorraine Ela, had a chance run-in with a grocery-store checkout clerk who had heard about it secondhand. Ela says she missed out on a lot of her daughter’s childhood “because I was a drunk.” She says she got sober eight years ago, when Megan was 15. Two years later, Megan became pregnant and moved in, and the two grew close. “Megan was fun, caring, a loving mom,” Ela says. “If you ever met Megan, you would fall right in love with her.”

Ela believes Megan was forced into prostitution. Her boyfriend, Akeem Cruz, worked as her pimp, accompanied her on calls, and posted Craigslist ads for her (Hi my name is lexy i have blond hair blue eyes great attitude. i love what i do ur time with me is never rushed…). Ela calls Cruz “a scumbag.” But Ela says Megan denied being a prostitute. “She tried to tell us for the longest time that all she was doing was dancing. But we knew different. We told her, ‘It’s not safe. You need to think of your daughter.’”

Megan was last seen at the Holiday Inn in Hauppauge, Long Island, on a Craigslist call. Cruz came with her; he had been arrested on a cocaine charge in Maine but was out on bail. He usually stayed with Megan on calls, but that night he left her alone. Cruz is reportedly back in prison now and is said to have been less than cooperative with detectives about what he knows about that night. Ela finds his behavior that evening suspicious: “He leaves her in the room alone that night, and she goes missing?”

Ela says that Megan had her own struggles with alcohol, and that that might’ve had something to do with why she stayed with Cruz. Since Megan disappeared, Ela’s mother, who took care of Megan while Ela was drinking, is looking after Megan’s daughter. “I have more bad days than I have good ones,” Ela says.

The most recent victim, Amber Costello, was last seen in North Babylon, Long Island, on September 2. Her sister, Kimberly Overstreet, makes no effort to sugarcoat her story. “Amber was a basket case,” she says. “She struggled most of her adult life with drugs. She was addicted to heroin. That was the biggest strike against her. Secondly, I was involved in this.” Trim, toned, and dimple-chinned, Overstreet has been escorting on and off since she was 18, and she’s the one who brought Amber into the profession. “I’ve done this, and it isn’t really about being naïve,” she says. “In the beginning you make the money, and you’re making it without the drugs and without the bullshit. And then you get addicted to the money.”

Amber and Kimberly grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina, and lived on and off together in Florida, then for five years in Long Island, about a twenty-minute drive from Gilgo Beach. “When she first moved to Suffolk County, Amber made $3,500 a week, easy,” says Overstreet. “In four months, it was $7,000. We traveled all up and down the East Coast doing it—Hilton Head, Florida, New Orleans.” Much of that was with an escort agency, but eventually Amber switched to Craigslist. By last year, Overstreet was getting out of the business, tapering off to about ten calls a week—she had three children—but Amber was desperate, making five calls a night. “She was doing calls for under a hundred dollars just to keep her drug habit going,” Overstreet says. “She was shooting bags a day, a bundle a day—a lot.”

A few months before Amber disappeared, Overstreet persuaded Amber to enter a detox program at Nassau University Medical Center, but while Overstreet was caring for their sick father back in Wilmington, she says, Amber relapsed. “Her daily routine was she would get up, she would take the train into the city, cop, come back, set up a couple calls,” she says. Overstreet was in North Carolina and unable to help Amber this time. When she went missing, “I thought, Well, she probably just met someone who is getting high with her. Those were my exact words.” She didn’t file a missing-person report. “I knew,” she says, “it wouldn’t be taken seriously.”

As they talk at the Tribeca hotel, the women take some comfort simply in being together. Cann is glad to be around people who understand her. “It’s amazing. I feel like I’ve known all these people my whole life,” she says. “It’s hard to talk to family,” Gilbert says. “It’s easier to talk to a stranger.” But before long, the conversation begins to bounce from one difficult subject to another. Cann is angry that people judge the victims because they were prostitutes. “I’ll always love my sister, and I’m proud of her no matter what anyone says,” she says. Gilbert is upset that people judge the victims’ families. “Some TV station said they were women whose families just didn’t keep in touch,” she says.

Cann has taken it upon herself to police anyone seeking to exploit the case. One target is Longislandserialkiller.com, a site that culls information about the case. “They were selling freaking T-shirts!” she says. She tells the others that she had the police shut down a rap video called “Ocean Parkway” that used photos of the dead girls without permission. (“The white girl had to get it because she could snitch on me/They killed you because you were a menace to society” went one lyric.) Barthelemy and Overstreet are reeling from multiple losses. “It’s tough enough to go through this,” Barthelemy says, “and a month later my mother dies and I’ve got to keep my whole family together.” “I lost my mom, and my dad is dying,” says Overstreet.

The women are too polite to zero in on Amanda right away, but it’s lost on none of them that Melissa’s little sister is the only person who may have spoken with the killer. “The media pounded the shit out of us to get the content of the calls,” Lynn says. “And we’re like, ‘We can’t let you know anything more than what’s already out there, because the only other person who knows what was said besides the police is the killer.’”

Still, the others can’t resist a question or two. “Can I just ask you,” says Overstreet, “did he sound husky, or brusky, or what?”

“No, he didn’t have an accent,” Amanda says. “He was white.”

“Did he sound like a New Yorker?” says Overstreet.

Amanda struggles to answer. “Not really. It was just kinda plain. You know, he was white, probably in his thirties, forties, maybe.”

“So he’s not from New York?” Cann asks.

Amanda shrugs. “Maybe,” she says. “He could have been.”

The questions come faster now: Was he angry, happy, nasty, mocking?

“He was calm, in control,” Amanda says. “He knew what he was doing.”

All five women are angry with the police. They don’t want to alienate them, but they can’t help but be upset by how slowly the case seems to be progressing. Gilbert lost her patience when the police asked her not to be interviewed on TV. “I said, ‘If you’re not going to do anything, I’m going to talk.’” Now, she says, the police don’t call her anymore.

To one degree or another, all of the women have taken on the role of amateur homicide investigator. “It’s like a little detective crew,” Overstreet says. They talk about how many cell phones the women used; how calls on prepaid disposable phones are harder to trace; whether salt from the ocean corrodes human flesh quickly or acts as a preservative. They compare notes: Did all the girls have the same driver? Did the police show every family a photo of a man with a lazy eye? Searching the web, Cann has lurked in the online bulletin board for the gated community where Shannan was last seen and discovered the message board where anonymous johns had been threatening to take revenge on Amber months before the press found it.

So little is known about the nights the other girls disappeared that the women tend to focus on the evening Shannan Gilbert went missing, replaying the details of what happened again and again, searching for clues to who the killer might be. No one engages in that exercise more than Mari Gilbert. Mari has signed on with a lawyer, former Los Angeles prosecutor and frequent Nancy Grace talking head Robin Sax, who has hired detectives to investigate the case independently; she has also paid for services to track down phone numbers and addresses of Oak Beach neighbors.

In the past year, Mari has developed a theory of what happened that night that implicates Joseph Brewer, Michael Pak, and possibly a man named Peter Hackett. Hackett is a neighbor of Brewer’s at Oak Beach. The day after Shannan went missing, Mari says, she received a phone call from a man claiming to be Hackett. The man said he ran a home for wayward girls where Shannan had been staying and was calling because she had left unexpectedly. He asked Mari if she knew where Shannan was. It was the first time Mari had heard Shannan was missing.

Mari didn’t know what to make of the call. Looking back, she can’t even be sure it was Hackett on the phone. If it was him, was he fishing to see if Shannan was all right? Was someone else doing that, using his name? What seems clear is that whoever was calling had reason to be concerned about Shannan. Mari became suspicious of Hackett. She says she came upon information suggesting that he plays some sort of security role at Oak Beach. New York has not been able to confirm this; Hackett, who has done police and EMS work in the past, has denied ever calling or meeting Gilbert.

Mari now thinks Brewer frequently brought girls to Oak Beach for parties and that Hackett knew. She suspects that Pak drove girls to other parties there as well. Even if Brewer, Hackett, or Pak didn’t kill the four girls who are confirmed dead, and even if they don’t know who did, Gilbert thinks they’ve been less than forthcoming about the murders and Shannan’s disappearance and could potentially provide useful information if they were more cooperative. The police have said repeatedly that Hackett, like Brewer and Pak, is not a suspect in the case. If Brewer, Hackett, and Pak were involved, I ask Mari, why would they leave the bodies so close to home? That’s the point, she replies. “Who would ever think?”

Shannan was in line to become their next victim, Mari believes. But Shannan, she insists, wasn’t like the other girls. She would not go quietly. “I think they underestimated her,” Gilbert says. “She knew, ‘This is not what I want to do.’ And without her running and screaming, none of these other bodies would have been found.”

The appeal of this theory is obvious; any mother would want to think her daughter stood up for herself. But Overstreet doesn’t think it happened quite that way. Drawing from her own experience as an escort, her theory is slightly less flattering to Shannan. She says she thinks Shannan got high with Brewer that night—even though he’s denied it. “He got this girl probably so blown out of her mind, because that’s how they are. They’ve got the drugs and they’ve got the money, and you’re there for the hour. Then, for whatever reason, he did something to spook this girl. That girl was scared for her life. Something made her think that somebody’s going to kill her.”

“She was hiding behind his couch, right?” Cann asks.

“She wouldn’t leave,” Overstreet says. “She’s scared. So Brewer calls the driver and says, ‘Shannan won’t leave.’”

But one detail still confuses Overstreet. “Why didn’t she run to the driver?” she asks. “The driver’s my safety. I don’t give a damn how fucked-up I was, my ass is going to the driver because that’s my way out—whether it’s the police coming or somebody trying to kill me.”

Gilbert offers an explanation. “Because when she was done with Brewer, she went back to the car to go home, and the driver’s like, ‘Where’s my money?’ And she says, ‘I don’t have any money.’ So he brought her back to Brewer’s, and Brewer said, ‘What are you talking about? I paid her.’ She said she’s tired of the driver taking all her money. ‘I’ve given you money every time, I want this money now.’ And that’s when they started arguing, and she hid in Brewer’s house.” Maybe Shannan ran off to safety, Gilbert believes, or maybe that’s when the killer got her.

The others want to know why Mari thinks Shannan suddenly wouldn’t share her fee with the driver. “I was the last one Shannan talked to that night, six hours before she was missing,” Mari says. “We had planned for her to come home for my birthday and for Mother’s Day.” Gilbert thinks Shannan didn’t want to give the driver his cut that night so that she could have enough money to buy her a present. “She said, ‘I have to work tonight, Mommy.’”

Everyone is quiet for a moment. The guilt permeating that theory is so overpowering no one wants to acknowledge it. Finally, Overstreet says something. “Okay. So you don’t know that conversation went on between her and that driver at that point? You’re just guessing?”

“I’m assuming,” Gilbert says tensely, “that when she went back to the driver and the driver said, ‘Give me the money,’ she said, ‘No, I need the money for my mom’s birthday.’” She pauses and locks eyes with Overstreet. “Because she told me, ‘I’m doing a job so I’ll have some money to buy you something for your birthday.’”

Overstreet has a wealth of information about what it’s like to be a Craigslist escort—the money, how calls are arranged, the risks, the drugs. To a point, she presents an alternative image of all the girls—a less innocent one than some at the table would care to think about. Like Cann, she knew right away that her sister was one of the Gilgo Beach bodies. But unlike any of the others, Overstreet sees in all these murders an alternate ending to her own life that she somehow escaped. “I was thinking, God, did I run across this person?” she tells me later. “And maybe I wasn’t his type?”

Overstreet almost says something else to Gilbert but then stops herself. “I’m telling you, I feel for you more than I feel for myself or any other lady here,” she says. “Because Shannan is still missing, you know? At least I know where my sister is. And if I don’t know nothing else, I have that closure.”

Jeff Marina, Lynn Barthelemy’s fiancé, seems to want to break the tension and bring everyone back together. “I just think all these girls, all our daughters, our sisters, whoever they are, I think they all met the same nut.”

But later, Overstreet presses her view again. “The connection between these four women is cocaine,” she says when we’re alone. “That wasn’t my sister’s drug of choice, but she had access to it. And if it was gonna make her money, she would do it. Shannan had a history of coke. Even though people won’t admit it in public, just do your research and you’ll see. So I think the killer likes to get high.”

If the police have a suspect or even a working theory of who the Long Island serial killer is, they aren’t saying. They seemed as surprised as anyone when a fifth victim was found on March 29, and three more on April 4, and two more on April 11. But the new discoveries didn’t fit the pattern. The bodies were discovered a significant distance from the original four sets of remains, and without burlap. One was identified as a prostitute killed back in 2003; another was a man; another a child. If nothing else, it’s now clear that Gilgo Beach has served as a dumping ground for corpses for years. While the victims’ families and others accuse the Suffolk County police of moving too slowly, officials are pleading for patience. “Please keep in mind this is not an episode of CSI,” Police Commissioner Richard Dormer has said.

In the absence of any leads, a number of theories have been floated in the press. The killer must know the area well, perhaps even be a local (how else would he be able to spend so much time there without being noticed?). He gets off on power, not sex (this would explain the phone calls to Amanda). He must have a background in law enforcement to have been able to evade detection (he was clever enough to use untraceable disposable cell phones to call his victims, proponents of this theory note, and his calls to Amanda were brief, all under three minutes, and from densely populated areas). The cop idea briefly gained momentum when the Post reported that two members of the NYPD, one active and one retired, were under suspicion, but the NYPD immediately denied it. For a while, reports spread that the case may be linked to an older mass-murder case of prostitutes in Atlantic City; the idea was that the killer might live elsewhere and summer on Long Island, which would explain why all five women disappeared roughly between Memorial Day and Labor Day. But that connection was eventually dismissed by police as well. The victims’ remains are another source of speculation. Why were the bodies so thoroughly decomposed? Did the killer mutilate the women for pleasure? Was he seeking to cover his tracks? Or did the bodies simply deteriorate in the salt air?

From time to time, law-enforcement officials have returned to Gilgo Beach to search for Shannan, fanning out across the bramble, sending cadaver dogs into the brush, and even using FBI Black Hawk helicopters equipped with high-resolution cameras to scan the area. They insist they continue to pursue all leads. But by all appearances, none of it has worked. The police seem no closer to catching anybody than they were the night Shannan Gilbert vanished.

The women gather again for dinner, where they talk about the joint vigil they’re planning on Ocean Parkway, along Gilgo Beach, on June 11. The purpose, Cann says, is to persuade people to come forward with information and keep pressure on police to crack the case. “I may never get closure,” she says. “But that’s still a place where my sister was. And I just feel like that community has to see the families. All they care about is the values of their houses and how their community looks.”

The women can’t understand why people aren’t as upset as they’ve been about similar cases. “Look at Natalee Holloway,” Overstreet says. “People should have been elbow to elbow out there, walking for this girl, Shannan Gilbert. Why not? What makes her disappearance any different?”

“They’re like, ‘We’re not worried because it’s not like a murder of regular people,’” Cann says. “I want that community to know that these girls had families that love them.”

“They don’t want the attention,” says Gilbert. “There’s doctors there, lawyers there, cops there. They don’t want to be associated with that kind of behavior.”

After dinner, we go back to the hotel lobby to say good-bye. The women seem wilted. The hugs start. “We’ll be friends till the end,” Ela says. “Even after they find him. We’ll all be friends till we all go upstairs.” Ela has handed each of the others identical trinkets she picked up in a shop in Maine before coming here. They’re little pink hearts with angel wings. “It’s because the girls are all in our hearts,” Ela says, “and they’re all in heaven.” The other women love them.

Gilbert likes the trinket too. “I always worked for, like, normal-class people, like $14 an hour,” she says. “But Shannan just liked really expensive things. I don’t know who she picked it up from.”

Gilbert remembers the night Shannan disappeared and their phone call. “I said, ‘Look, Shannan, you coming is my gift. You don’t have to bring me a present, just come home.’” After hanging up, she texted Shannan: Be safe.

And right away, her daughter answered: I always am.