Clay D., a moon-faced man in his early thirties who, by his own matter-of-fact admission, has spent a good deal of his life “shooting at people” in and around Newark, New Jersey, was talking about his first attorney-client meeting with lawyer Paul Bergrin.

“Someone got killed, and they were trying to put it on me,” remembers Clay, as he asked to be called. “First-degree murder, can’t fuck with that, so I got Paul. He was the biggest name out there. He drove his Bentley down Clinton Avenue, and it was like, ‘Don’t you punks even think about jacking that.’ Everyone said he was wide open. But I didn’t know how wide open until that day. I’m in his office two minutes. He says he’s looked at my case, and only one witness can hurt me. Then he says, ‘Okay, what are we going to do about this person? She’s a user, right? Why don’t we give her a hot shot? Just stick her.’ ”

Asked if it bothered him to hear his attorney suggest such a course of action, Clay laughed and pulled up his shirt to reveal several scars on his abdomen, the result of being shot three times with a pistol. As chance would have it, the shooter was another of Bergrin’s clients, Clay said, not that this mattered.

“Just not my time,” Clay said nonchalantly. Two of the bullets passed harmlessly through his body. Another slug lodged in his stomach muscles. “I was working out, had abs like a rock. They stopped the bullet.” This was how it was on the streets in Central Newark, Clay said, kill or be killed. East Orange and parts of Irvington were no better. You got rich one day, were blown away the next. It was a different world out there, with completely different rules.

“That’s why I needed Paul,” Clay said. “I can’t have some bullshit lawyer in suspenders and I’m supposed say thanks because he got my sentence down to twenty years. I’m paying top dollar, and I demand legal brilliance. Someone who will consider all the options. I don’t want no loser. I want a winner … Paul Bergrin was a winner. Let me tell you, whatever happens to him, there ain’t ever gonna be no other lawyer like Paul Bergrin.”

In New Jersey, nothing beats Essex County, 130 square miles of urban melodrama stretching from the now sudden-death ghetto streets of Philip Roth’s old Weequahic Newark neighborhood to the big-as-the-Ritz engagement rings at the Short Hills Mall. Famous crooks who have plied their trade this side of the Pulaski Skyway include Lucky Luciano, Longy Zwillman, and Richie “the Boot” Boiardo, who, legend has it, burned his enemies’ remains in the furnace of his castlelike Livingston home. Equally greedy, if less folkloric, has been Essex’s epic succession of corrupt politicians, voted in and not. Good luck to Cory Booker, everyone’s favorite walking infomercial for well-tailored municipal uplift, but the smart money is against him. The last three Newark mayors were convicted of one charge or another.

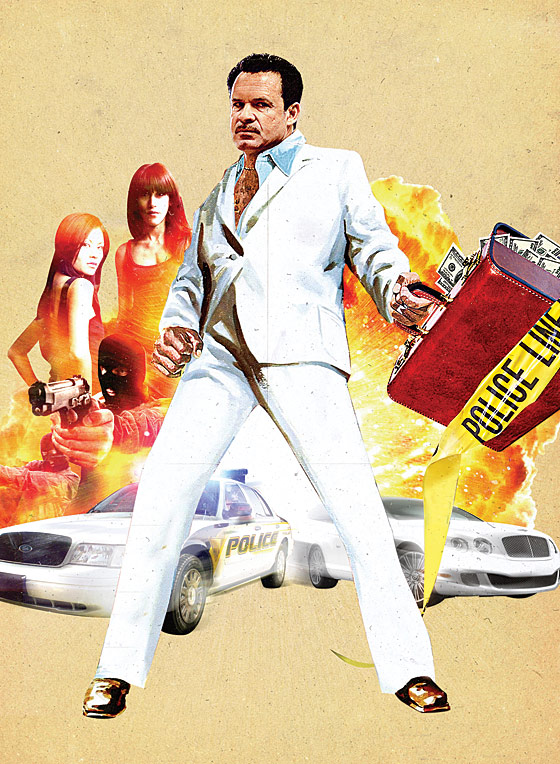

A strong candidate for addition to this list—in a twisted legalistic category all his own—is the 55-year old Paul Bergrin, Esq., who awaits trial in a federal lock-up facing charges that are a good bet to keep him behind bars for the rest of his life. Advocate to killers, whorehouse proprietors, bum-check-passing beauty queens, Lil’ Kim, and a thousand forgotten street hoodlums from Newark’s bad wards, Bergrin has run the gamut of Jersey jurisprudence in his 30 years on the scene. In the early eighties, following a stint in the Army, Bergrin joined the then–legendarily kleptocratic Essex County prosecutor’s office, where he forged a reputation as a square-jawed inquisitor of the local criminal class. In 1987, Bergrin moved up to the exalted precincts of the United States Attorney’s Newark office, where he served under both Samuel Alito and Michael Chertoff. Men like these did not stuff envelopes of cash into their pockets in parking lots; they joined the Supreme Court and ran the government’s response to Hurricane Katrina. By 1991, Bergrin, whose courtroom self-presentation often included swank Brioni suits offset by a skeevy pencil-thin mustache, was in business for himself, becoming one of the most controversial, and high-billing, criminal-defense attorneys the county had ever seen. His 2009 arrest completes the possibly fated Essex full circle.

Despite Bergrin’s hopes, expressed in an e-mail, that God provide the neutral observer “the wisdom to see through this indictment and case,” the government brief against him is comprehensive. According to the 95-page document, Bergrin, in rough ascending order of immorality, (a) operated a real-estate scam that defrauded lenders of over $1 million; (b) ran a high-volume drug dealership big enough for 120 pounds of uncut cocaine to be found at a North Newark restaurant owned by Bergrin’s mistress and co-defendant, Yolanda Jauregui; and, most spectacularly, (c) set up witnesses to be murdered before they could testify against his clients.

Cornerstone to the government’s case against Bergrin are the alleged events of March 2, 2004, when Kemo Deshawn McCray was shot in the head three times while crossing the intersection of 19th Street and South Orange Avenue in Newark. The Feds contend the murder was the culmination of a chain of events that began when McCray, a federal informant (i.e., snitch), purchased a quantity of crack cocaine from one William Baskerville, a lieutenant in the drug posse run by his cousin, Hakeem Curry, the fearsome “E. T. Hak,” Newark’s then-reigning dope kingpin.

Snagged in the buy-and-bust, Baskerville was represented by Paul Bergrin, reputed “house counsel” for Curry’s organization. It was during one jailhouse attorney-client meeting, the Feds contend, that Baskerville told Bergrin that Kemo McCray had fingered him. If so, McCray figured to be a convincing witness in any trial. According to federal wiretap evidence, Bergrin discussed the problem with Curry, who paid assassin Anthony Young $15,000 to kill McCray. The Feds maintain that Bergrin signed off on this solution, offering the succinct legal opinion, “No Kemo, no case.”

There was more. According to the indictment, in 2008, Bergrin traveled to Chicago, where he attempted to hire a hit man to rub out a troublesome informant in a case against another client, accused drug trafficker Vicente Esteves. The “hit man” turned out to be a government witness who recorded his dealings with Bergrin, including a snippet where the lawyer allegedly laid out the murder plan. “I got it all figured out,” Bergrin is quoted as saying. “Put on a ski mask and make it look like a robbery … It cannot under any circumstances look like a hit.”

The indictment stunned even the most jaded Essex County observers. One well-known lawyer whose career in the area goes back to the early seventies, said, “If Paul is guilty of half the things they say, he’d be the craziest, most evil lawyer in the history of the State of New Jersey. That is saying something.”

It is now two years since Bergrin’s arrest. Denied bail, he awaits his long-delayed trial (now scheduled for October) in Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center, where he spent several months in solitary confinement, apparently at the insistence of the Feds. “Mr. Bergrin participated in numerous plots to kill witnesses,” Assistant U.S. Attorney John Gay said at his bail hearing. “If he is willing to go to those lengths on behalf of his clients, he is certainly willing to do it for his own freedom.” But if Bergrin has been out of sight, he is far from out of mind, especially on Park Place, the block-long stretch in downtown Newark where many defense attorneys have offices.

This is Newark’s criminal-justice Tin Pan Alley, where the jammed-up, at least those with enough money to avoid the public defender, come to seek representation. At any one time there can be half a dozen breaking-and-entering men, dope pushers, and members of who-knows-how-many sets of Brick City Bloods sharing an elevator ride with cleaning ladies and misdirected guests from the nearby Robert Treat Best Western Hotel. Few Park Place lawyers are of the white-shoe variety. “A lot of them were cops, went to law school at night,” said one longtime observer of the scene. “They’ve seen it all and don’t care all that much whether their clients are guilty or innocent. They’re there to win cases, nothing more or less.”

Paul Bergrin, graduate of Nova Southeastern law school in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for a time was the biggest fish on the street. Parking his Bentley and BMW in the lot around the corner on Mulberry Street, Bergrin met his clients, people like Angelo “The Horn” Prisco, a Genovese caporegime, and ranking Latin King coronas, in his huge office on the tenth floor at 50 Park Place. And for legal eagles who continue to work here, their fallen former colleague remains an unsettling, cautionary, obsessed-about presence.

With the trial still pending, the U.S. Attorney’s office had issued a neo-fatwa against talking about the case—no surprise since everyone knew the Feds had a particular hatred of Bergrin. How could they not? First he works in their office, then he supposedly helps murder one of their witnesses. Also galling was the fact that they’d earlier mishandled a piece of wiretap evidence, blowing a previous attempt to indict him in 2005. They weren’t taking any chances this time.

Still, it was hard to stop talking about Paul Bergrin. Almost everyone on Park Place knew him personally. Many remembered him as “a good guy,” the sort who would “give you the shirt off his back, lend you $10,000 without even blinking.” However, when it came to Bergrin’s insistence on his total innocence, eyes began rolling—especially in regard to the disappearance of witnesses.

“ ‘No witness, no case’—that was Paul’s motto,” said one attorney. “There was this guy with a tattoo of the scales of justice on his back. Below the scales was the quote, ‘No witness, no case—Paul Bergrin.’ When your customers are all criminals, what’s better advertising than a prison tattoo?”

Everyone had his Paul Bergrin story—how he started off with one client, then switched to another defendant in the same case, got the second guy to flip against the first, and kept the money from both. There were tales of how Bergrin planned to open a $30 million gambling casino in the Costa Rican cloud forest. And of course, there was the whorehouse deal. Bergrin had taken control of one of Manhattan’s ritziest escort services and started bringing a steady stream of cops, lawyers, and even a prison official to the brothel’s Worth Street headquarters, where the samples were free.

Bergrin had gone rogue all right: “He’d crossed the line.”

It was a phrase that came up over and over again—the line, that border between what was allowed and what was not, the edge over which the rule of law dropped into Hobbesian free-for-all. In places like Essex County, with the tragic legacy of the 1967 Newark riots and its more or less permanent poverty class, definitions of right and wrong tend to be more pliable than a stone tablet brought down from Sinai’s. But even here, there was a point of no return.

In retrospect, Park Place lawyers noted insufficiently heeded red flags. Times when they should have “known.” Said one former associate, “these stone-cold criminals would come to the office, and Paul would say he ‘guaranteed’ he would get them an acquittal. How do you guarantee an acquittal?”

“I always regarded Paul as a good lawyer,” said another colleague. “No one worked harder or was better prepared. But he’d always be bragging about how he won fourteen straight homicide cases. Clarence Darrow can’t win fourteen homicide cases in a row, but Paul Bergrin can. When someone starts winning unwinnable cases, you notice. But never in a thousand years would I have imagined he would go this far. I mean, dealing dope out of your law office, killing witnesses? Who does that?”

There isn’t much background on Bergrin, other than his own version. Son of a Brooklyn cop, he says he was considered “incorrigible” and sent to a Brooklyn boys’ home. At 17, he enlisted in the Army, eventually becoming a member of the elite 75th Ranger Regiment. He married his high-school sweetheart, had children, and lived in Marlboro, an upscale community in Monmouth County where he is remembered by neighbors as “totally normal … just another dad down the block.” But as most who worked with him say, there was another side that was off-limits. “Paul was easygoing, accessible. But then there would be these time he’d go into his office and lock the door. You knew something was going on and you better stay away.”

Asked if there was any moment when Bergrin might have first crossed the line, several pointed to an incident during his tenure with the U.S. Attorney in the late eighties. With his Nova diploma, fractured grammar, and rough-hewn Essex-prosecutor manner, Bergrin was an odd fit with the federales. He put a large-size pinup calendar on his wall. But he had something his Harvard colleagues did not. While they had busied themselves preparing A-plus briefs, Bergrin had been facing down Essex County juries. “He had a lot of experience and carried himself like a hard-charger,” said one lawyer who served in the U.S. Attorney’s office along with Bergrin. “Some people found that intimidating.”

The event in question centered on a 1989 corruption case the Feds were pressing against two investigators from the Essex County prosecutor’s office. The defendants were widely regarded as “filthy,” and the case appeared routine. Until, that is, Assistant U.S. Attorney Paul Bergrin surprisingly took the stand as a character witness for one of the defendants. He worked with the man when he was county prosecutor, Bergrin testified, and he’d found them to have “a reputation for truth, veracity, and integrity.”

Recalling the episode more than twenty years later, one judge remained nonplused. “Here you have someone who is working for the government testifying against the government. This is what might be called a questionable career move.”

“They didn’t fire him,” said one of Bergrin’s U.S. Attorney colleagues. “They just took away all his cases. He’d come to work, and there would be nothing for him to do. For Paul, that had to be hell. Eventually he quit.”

What happened remains a mystery. Why would someone so ambitious—Bergrin often said he dreamed of being a U.S. senator—throw away a job that had catapulted people like Rudy Giuliani to stardom? Some thought the Essex investigator had something on Bergrin and had blackmailed him into testifying. For his part, Bergrin contended that he was his friend, and when friends are in trouble you come through, no matter how much it costs you.

“For anyone else, it would have been a setback, a career-killer. But Paul made it work for him,” said one prosecutor. Taking the local side against the haughty Feds, the jurisdictional town over gown, was an ultra-Jersey stiff finger for all time—an act worthy of an Essex County Machiavelli and one that would pay off big-time. “Even then, Paul was playing to the street,” said a Park Place lawyer. “He knew where the money was.”

Bergrin first hit the papers as a criminal lawyer in 1991, during his defense of a housewife accused of serving teens Jell-O shots at a party; a 15-year-old guest was hospitalized and died an hour later. By 1992, he was already under indictment for evidence tampering in a federal racketeering case. The charges were dropped two years later, setting the pattern for what would become a twenty-year legal tightrope walk.

Few denied Bergrin was an exceedingly talented, if occasionally overwrought, courtroom performer. “He had that military thing about him from his Army days,” said one observer. “He commanded the room. But it was more than that. Paul was passionate. This is Newark. Most of the defendants are black, and here was this white guy who seemed to really give a shit whether his client went to jail or not. In a place where today’s juror is tomorrow’s defendant, that connects.”

Said a local hustler with “double-figure” arrests behind him who I’ll call “Melvin B.,” “I’ve had a hundred fucking lawyers in my life, and Paul Bergrin was only one who looked me in the eye like a man. He cared. He knew the reality, how the deck was stacked, and was willing to fight fire with fire. He went to war for you. That’s why Paul was loved in the streets. Shit, Paul was revered in the streets.”

“Bergrin knew how the deck was stacked. He was willing to fight fire with fire. That’s why he was loved in the streets.”

Then, casually, Melvin let drop that he had done “a little legal work” for Paul Bergrin from time to time. “Yeah, I might have fixed a jury or two.” It was easy, Melvin said. “You don’t have to win; a hung jury is good enough.” Melvin explained his M.O. First he got himself into the jury-pool room. “When you’re a black man in Newark, you’re always going to know someone or someone who knows someone. You ask around. Find out who’s on which jury, make a deal. But sometimes they’ll come to you.

Listening to a description of a well-known Bergrin case in which Melvin claimed to have given a juror $10,000, one prosecutor exclaimed, “That’s exactly what I heard!”

This was the problem going up against Paul Bergrin in court, the prosecutor said. He was smart and without conscience. He knew the street, and he knew the system too. He knew how the prosecutor’s office worked, the calendar issues, the money constraints, when the bureaucrats would throw up their hands and drop the case. He had people on the inside. He made it his business to defend cops who got themselves in trouble and did work for the PBA. “That buys a lot of loyalty,” one prosecutor said. “When you had a lead in a Paul case, you had to act fast because you worried some cop would tip him off.”

Eventually, the prosecutor’s office investigated a number of Bergrin cases in which witnesses suddenly recanted or were killed. These included a 2006 trial in which Bergrin’s client James Dawson was acquitted of murder following the death of the key witness, Syreeta Lee. Bergrin said, “The only witness was Syreeta Lee. She is now dead. So there is no other evidence against my client.” Another Bergrin client, Norberto Velez, was charged with trying to kill his wife, repeatedly stabbing her in full view of their 8-year-old daughter. At trial, the child changed her story, absolving her father. Later the girl admitted in open court that Bergrin had coached her to lie on the stand.

It was awful, heartbreaking stuff, the prosecutor agreed. But, still, even with all he knew, he couldn’t find it in his heart to hate Bergrin. “What can I tell you, part of me still likes the guy. It is a strange thing.”

For all his transgressions, emotionally it isn’t an open-and-shut case with Bergrin. Many in Newark are highly sympathetic to Bergrin’s persistent defense of American soldiers accused of crimes during the Iraq War. In 2004, Bergrin defended Sergeant Javal Davis of the U.S. Army 372nd Military Police Company, who was charged with abusing Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib prison. According to witnesses, Davis, a onetime track-and-field star at his Roselle, New Jersey, high school, twice jumped onto a pile of naked prisoners. Davis was also said to have accompanied Lynndie England in stomping on detainees’ fingers and feet.

Declaring that Davis was only following orders, Bergrin requested subpoenas for Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and President George W. Bush. They were the ones who changed the rules of engagement regarding treatment of the enemy, Bergrin charged, not Javal Davis. Colleagues recognized the subpoenas (which were denied) as typical Bergrin grandstanding, a histrionic ploy from the Park Place playbook. But it struck a chord with Fran Hunsaker, mother of William Hunsaker, a member of the 101st Airborne Division who was accused of participating in the 2006 execution of three suspected Al Qaeda operatives near Samarra. Hunsaker was eventually sentenced to serve eighteen years, but Fran Hunsaker remains “eternally grateful to Paul. He was the only one who really stood up for those boys. He made five trips to Iraq at his own expense. He was a David against an army of Goliaths. That’s why he’s in trouble now. That indictment is one big lie. I know Paul, and that’s just not him. His soul is good. I think of my son Bill in Leavenworth and Paul in jail in Brooklyn and see them the same way. Two innocents crushed by a corrupt system.”

Bergrin agreed with this sentiment. In a series of e-mails sent from his Brooklyn cell, the Iraq cases were the only thing he wanted to discuss. It was like the rest of that stuff never happened. He saw defending members of the American military as a solemn duty. Several of his relatives had served in the armed forces, Bergrin wrote. “All I ever dreamed of was following in their footsteps.” To him, the plight of the American soldier was no different from that of “the vast majority” of the people he defended in Newark. As he told a reporter during the Davis trial, “the pressures on an Army or Marine captain and a Bloods crew leader are the same. These guys are soldiers, pawns in the game, thrown into battle, and no one cares what happens to them.”

This was the core of the matter, as Bergrin explained on a YouTube video called “Know Your Rights,” in which he tells an East Orange community group that if he’d learned anything in his legal career, it was that police could not be trusted to tell the truth. “If you ever sit on a jury … if you ever have an opportunity to speak to other individuals, then let them know that we live in a system where people are treated differently, and the only way you can fight it is by pouring your entire body, heart, and soul into each and every case. And that is what I intend to do.”

On Park Place, such commentary did not go unnoticed. “Paul said he was a street lawyer,” said one attorney, “that he functioned according the laws of the street, not those made up to serve crooked politicians and protectors of power. He sounded like some sixties radical. And I thought, Well, he’s right. Things aren’t fair. The system sucks. I see the inequities every day. Hearing Paul talk like that made me think he could have really been something, a leader, an inspiration. I also thought, if this is what Paul believes, and that’s his justification for everything he’s done, he’s out of his fucking mind.”

This has become a key point of discussion on Park Place: Bergrin’s mental state. Words like “megalomania,” “narcissist,” and “sociopath” have been bandied about in the buffed hallways of the Essex County courthouse.

On this topic I submit an encounter I had with Bergrin back in 2005, when I was working on a story on the demise of NY Confidential, the aforementioned escort service near City Hall. Jason Itzler, the agency’s mercurial founder, was then imprisoned on Rikers Island, facing prostitution and money-laundering charges. Itzler was not worried, however. He had unshakable faith in his lawyer, Paul Bergrin.

“I was still on parole from this Ecstasy-smuggling bust at Newark Airport and had a 9 p.m. curfew, which was messing up my ability to run the agency,” Itzler said. “So I went to see Paul. I heard he could fix anything in New Jersey. I tell him my problem and he says, ‘Okay, give me $10,000! Right now! In cash!’ I told him I only had $8,000. He said, ‘But you’ve got the rest at your place. Let’s go.’ We get into his BMW, barrel through the Holland Tunnel. Paul looks at the murals, the baby grand piano, the girls. ‘Forget the $2,000,’ he says. A few days later, Itzler had a no-show job as a paralegal in Bergrin’s law office, supposedly working until three in the morning on difficult legal matters like the Javal Davis case. Bergrin wrote letters to the parole board attesting to Itzler’s excellent progress toward rehabilitating himself.

“I loved and trusted Paul,” Itzler summed up. “The one thing I never expected was for him to leave me to rot on Rikers Island while he put the agency in his name and took it over completely. I probably should have seen it coming, but I was so high on Special K I didn’t know which end was up.”

Back in 2005, Bergrin was happy to talk about NY Confidential, but he asked if we could meet near Mount Sinai hospital. He was tired of the law, Bergrin said. Thinking he might better serve his fellow man as a doctor, he told me he was attending medical school. Wearing a slick blue suit and red tie, his thick mat of dyed black hair receding from an expansive forehead, Bergrin was friendly in a gold-cuff-link way, handing me the phone number of the famous Natalia, NY Confidential’s much-ballyhooed No. 1 attraction. “You’ll like her,” he said with a wink. Then, checking his watch, he said he had go to class. It was a basically uneventful conversation, except Bergrin was apparently not attending Mount Sinai or any other such institution. Why he went through all the trouble I never knew.

Bergrin’s 2007 arrest in the NY Confidential case, in which he was charged with laundering more than $800,000 in the agency’s proceeds, was the first tangible clue to many on Park Place that the lawyer had seriously jumped the tracks. What wasn’t a surprise was the sex angle. Said one longtime associate, “Paul didn’t drink, didn’t take drugs, but with women, he was a madman. White, black, skinny, fat, good-looking, ugly, crack whores, how and where, it didn’t matter. He’d make this cocktail, Viagra, Cialis, Levitra, and wash it down with Red Bull. He said it made you fuck all night. I told him he was going to give himself a heart attack, but he didn’t care.”

Central to Bergrin’s hectic love life was his longtime mistress and alleged partner in the dope business, the diminutive Yolanda Jauregui, with whom he shared an apartment in Nutley while maintaining his stately home in Marlboro with his wife, Barbara, and their children.

“Yolanda had Paul by the balls. He was probably supporting most of her family,” said one lawyer.

Even though Yolanda was insanely jealous, Bergrin continued to screw around. Said one lawyer, “I come in the office, and Paul is totally on edge. He says he has a chick up at the Robert Treat Hotel and gives me a couple hundred to get rid of her. I knock, this hand comes out, snatches the money, and the door slams. Then I hear, ‘Tell that fuck it’s going to take a lot more than that.’ I told Paul, and he flipped. He said if Yolanda found out, she was going kill him. She might have, too. Everyone in the office was scared of her.” On a number of occasions Bergrin showed up at the office with black eyes or a bandaged cheek. “Everyone was sure Yolanda slugged him.”

When he announced the indictment, in May 2009, then–acting U.S. Attorney Ralph Marra said Bergrin “essentially became one of the criminals he represents.” No one disagreed with that. But somehow simple condemnation seemed too easy in Bergrin’s case. The story was a tragedy, but it was a particularly Essex County kind of tragedy.

Bergrin’s current legal adviser, Lawrence S. Lustberg, graduate of Harvard Law, cum laude, 1983, said to have been shortlisted for the A.G. job in President Obama’s cabinet, is not a Park Place lawyer. Lustberg said he took Bergrin’s case because “originally they were asking for the death penalty, which was outrageous. I also had my doubts that Paul could get a fair trial in this environment.” Attacking the government’s rico indictment against Bergrin, Lustberg said he will try the case “on the law.”

On Park Place, however, there are doubts about this strategy. “Larry Lustberg is a brilliant attorney,” said one barrister. “But you can’t try this case on the law. You have to pull something out of left field. Something the jury will believe.” Asked what that might be, the lawyer said, “Insanity! If Paul himself was trying the case, that’s what he would do: Stand up straight, with that military bearing, look the judge straight in the eye, and say, ‘Not guilty, your honor, by reason of insanity.’ ”

There is evidence to support this theory. First of all, it is virtually impossible that Bergrin did not know the Feds were monitoring his actions. They’d been after him since the Kemo McCray murder, reputedly tracking his every move. Yet he continued on his hellbent course, allegedly conspiring to eliminate witnesses, fixing cases, selling drugs. Personally instructing the government “hit man” to “put on a ski mask” was not even the topper. Later transcripts detailed how Bergrin supposedly expressed a desire to personally take part in the rubout, much to the horror of the “hit man.”

Beyond this is Bergrin’s increasingly bizarre behavior. “In the last couple of years he started telling everyone he was dying,” said one Essex lawyer. “But he wasn’t going to take any chemo. That was for pussies. He was going to face the disease like a man. Everyone was really sorry for him. He started using it as an excuse to get out of trying cases,” the lawyer said. It was as if Bergrin’s total obsession to win every case had morphed into an all-consuming fear of losing. “It got so he didn’t want to do any cases outside of Essex County. And if one of those cases started to go south, that’s when he’d get sick. Someone else from the firm would step in. That way, if it was a loser, it didn’t go on Paul’s record.”

The cancer, if cancer there was, has not been mentioned since. “He was the best-looking terminal-cancer patient you ever saw,” said one colleague. “One day a friend of mine saw him running through the courthouse parking lot, and Paul turns around, yells ‘Remission!’ and keeps going.”

Now entering his third year behind bars, Bergrin says he is using his prison time to get closer to his Jewishness. He prays each morning with tefillin and thinks about “the suffering experienced by our people.” He has also completed his memoirs, which he says will “enable the fair-minded reader” to “see through this indictment to objectively determine the truth, whole truth, and nothing but the truth. There was not an attorney in the United States who worked harder than me, served his fellow soldier with more dedication, and loved his children as much as me.” He predicts the book will be “a national best seller.”

Back in Jersey, Bergrin’s legend grows. Like Bonnie and Clyde, the roster of crimes he supposedly committed, cases he fixed, expands by the day. His name has turned up in the lyrics of East Orange rappers.

“He’s a local legend,” said one Essex prosecutor. “Paul was made for this place. He might have done terrible things, but it was Essex that helped him get away with it. Face it, criminals have been running things here for a hundred years. When you walk into a courtroom and a whole row of guys you know are Bloods are sitting in the back row, who is going to testify then? No one believes what the cops say on the stand. They haven’t, really, since the riots. If there was ever a place for which the phrase ‘It is what it is’ was made for, it is Essex.” For all the good intentions, a lot slipped through the cracks, which was just the sort of environment where someone like Paul Bergrin could work out his own particular criminal drama.

Meanwhile, the wheels of justice grind on. Over the past year, Thomas Moran and Vicente Esteves, both named in the indictment, have made deals with the Feds, likely “flipping” on Bergrin. Only last month it was reported that Yolanda Jauregui had followed suit, pleading guilty to racketeering, conspiracy, and drug-dealing charges. It is expected that Bergrin will also flip, if he hasn’t already, and start singing about his life and times as New Jersey’s baddest lawyer.

“There’s some cases over at the U.S. Attorney’s office that might be coming from Paul,” said one Essex County judge.

Asked who might be sweating, the judge laughed. “The question is, who’s not?” he said.