1971

A con fools one mark, a scam a whole school of them. The ambition of a hoax is much grander, to sucker the whole world, which means it’s an absurdist fantasy more or less doomed from the start. Or maybe not, if the huckster is savvy enough to pick an unwitting shill who’s so completely ascended into myth and innuendo that people only doubt stories about his life when the dispatches seem to arrive from the real world.

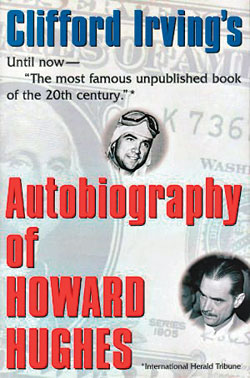

By 1970, when a novelist named Clifford Irving living in Ibiza hatched a plan to cash in by publishing an entirely fabricated “autobiography” of Howard Hughes, the billionaire tool magnate, aviator, and gonzo movie producer was not just our richest recluse but the most famous, legendary for being legendarily weird: Michael Jackson by way of Citizen Kane, Charles Manson, and Tony Stark. That he was scheduling a rendezvous with a secret biographer on top of a Mexican pyramid seemed perfectly plausible. Much likelier, anyway, than that he was engaging in a snippy he-said-he-said fight with a small-time writer over whether a book was actually “real.”

Hughes, hearing of the 1971 McGraw-Hill book deal, made an angry call to Frank McCulloch, who’d been the last man to interview him. It was the first time he’d been heard from in years; McCulloch took the call but, ultimately, Irving’s word. Hughes then staged a conference call to denounce the book. But Irving was much more sensible-seeming on 60 Minutes a week later. Mike Wallace believed him.

Most journalistic hoaxes are amateur-hour operations, delicious because the stakes are so low and the pigpen so small. But Irving’s was impeccably planned. He’d forged letters so perfectly that experts authenticated them. He had McGraw-Hill send Hughes’s checks to a Swiss bank, where Irving’s wife collected them, with a false passport, as “H. R. Hughes.” Most important, he had lucked into an unpublished biography by a Hughes confidante—and appropriated it, much of it nearly verbatim. The “autobiography”—now an icon of writing in bad faith—therefore had the unfortunate problem of being largely true.

Much of it, anyway: It soon emerged that on the dates of Irving’s supposed meetings with Hughes, he had in fact been “meeting” with mistresses. Confessing, Irving had to return the $750,000 advance, but his follow-up tell-all reportedly netted a $500,000 offer. When that book was made into a movie in 2007, he insisted his name be removed from the credits—it took too many liberties, he said.

From the Archives: ‘The Downfall of Clifford Irving,’ (May 15, 1972)