Matt Badger believes that what happened happened for a reason. That his children were born in order to live in order to die the way they did, that out of it something meaningful must come. If at any point it becomes clear to him that he is wrong, that what happened is instead an anecdote of the universe’s brutal indifference, then he will kill himself.

This kind of faith renders all starting points equally as relevant and moot, including that early morning of December 25, 2011, in Stamford, Connecticut, where, on the peninsula of Shippan Avenue, Engine 4 was racing, sirens blaring. Inside 2267 Shippan, a 116-year-old Victorian house, three girls—Lily, 9, and her 7-year-old twin sisters, Sarah and Grace—had wanted to make a fire on Christmas Eve. Michael Borcina, the contractor working on the house for the past year, whose relationship with the owner, Madonna Badger, had recently turned romantic, placed a bundle of wood and two Duraflame fire-starters in the fireplace in the living room. The fire was warming the newly opened-up first floor by the time Madonna’s parents, Lomer and Pauline Johnson, arrived from Lomer’s final shift playing Santa Claus at Saks Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. The artificial tree was lit; the stockings were hung. Earlier in the day, the girls had played outside, riding their bikes in the street. Grace lit electric candles. Madonna cooked a ham dinner. She was, at 47, among the most successful advertising executives in New York City; she had recently divorced her husband and had bought the house the previous December. Renovations were only now finally inching toward completion; despite wishing everything to be perfect for the holidays, Madonna had called off the painters who’d been scheduled to return that morning.

At 10 p.m., the girls were herded up the stairs to their pink-and-white bedrooms on the third floor. They believed that Santa Claus was nearing the air above Connecticut. It was difficult to get them to sleep. Borcina, who’d been staying in the three-car garage out back and was spending his first night in the house, read aloud Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas to the children. Lily was, despite being the oldest, always the most sensitive, and she made a fuss about not wanting to sleep alone; she and Sarah fell asleep together, in the twins’ turreted room. Grace ended up in bed with her grandparents.

Madonna and Borcina commenced wrapping gifts in the garage out back, where their cache was secreted. It was 3:32 a.m.—Madonna glanced at the clock—when they returned through the kitchen with their arms full of presents. They arranged them under the tree. The fire was long out. Madonna asked Borcina to prepare the fireplace, which was unkempt with spent ashes, for Christmas morning. He separated the partially burned logs, shoveling the ash into a paper shopping bag, running his hands through them to make sure they were cold, then placing the bag inside an empty plastic storage box. He deposited the bag in the mudroom, near 43 unused Duraflame logs Madonna had purchased from Stop & Shop. He washed the soot from his hands in the new, deep sink. They ate apple pie and drank milk and tea. It was late. Rounding the corner to climb the narrow butler’s stairwell off the kitchen, Madonna glanced into the mudroom. She flipped off all the lights.

She lay down in bed with Borcina in the back rear-corner bedroom and accidentally fell asleep, waking sometime after 4 a.m. to his tapping her. She made her way to the second-floor master bedroom that composed the entire front of the house and a corner facing Long Island Sound, slid the pocket doors behind her, and fell into bed.

Outside, it was 28 degrees. A breeze from the northwest blew at six to eight miles an hour. The only sound was of the sea gurgling and hissing and intermittently slapping. Inside, it was dark; near the kitchen, beside the basement stairs, the keypad for the new fire-detection-and-security system, not yet powered, was dark, too. In the mudroom, inside the brown paper bag, it had begun, the process of deterioration favored by all molecules on Earth, now accelerated by combustion, blackness spreading across the surface of the ash like oil pooling, giving way to white wisps of smoke, the suggestion of incandescence, ruddiness, finally: fire.

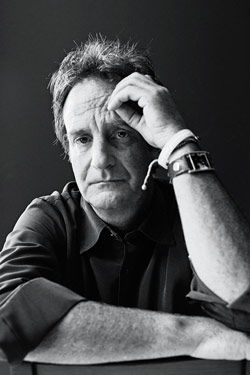

When Matt Badger comes downstairs from his apartment in Battery Park City, wearing jeans and an untucked olive button-down shirt, there are two children playing in front of his building, a girl with bright-red hair pushing another girl on a scooter. He looks at them and smiles. He does not appear well.

Eight months have passed since a knock awoke him and his girlfriend, Abby Ballin. He had ignored two calls on his iPhone around 7 a.m., assuming it was the girls calling to share what Santa had brought them. He and the girls had spent the week in the city, decorating his Christmas tree, ice-skating, and swimming in the pool in his building. It had been 24 hours since he’d dropped them off in Stamford. The knock persisted, and he stumbled past the tree and opened the door; there were two men in police uniforms who wanted to know if he was Matthew Badger.

Today, it is difficult to read his affect. He is short, attractive, and noticeably aging. He is aggressively smoking a Marlboro Red and preparing to light another. He wears necklaces around his neck, some leather, some metal, one a miniature version of Himalayan prayer flags.

He tells me that seeing children can sometimes make him feel better and other times worse. The last photo ever taken of the girls—of the three of them in brightly colored winter coats, lined up with him in front of the Hudson around sunset—was taken right over there. He speaks slowly, sometimes stuttering, not always in complete sentences. He has a diluted British accent, a vestige of his childhood in England. He says he needs caffeine.

We go to a coffee shop in the neighborhood. He orders a scone, a double cappuccino, and an iced tea. We sit in the sun. In between cigarettes, he chews Nicorette gum. He talks about the girls. He would take them to museums, parks, toy stores, dinner at the local diner, late movies, allowing them to run up in front of the screen to dance as the credits were rolling. He says he was too loose with them. Madonna had called him her fourth child; he says that she was right. He will not say anything else about her. She is struggling and trying to deal in her own way, and he does not want to hurt her.

He wants to talk about the foundation, the LilySarahGrace Fund, that he started in the days that followed the fire, days when he stalked his apartment like a lunatic, threatening to end his life, and others’: the town officials, Borcina, Madonna. Abby and his friends did not leave him alone, fearing for his safety. One day, sobbing in the shower, he came up with the idea. Like Matt, his daughters had all had dyslexia, expressing themselves first in art, so he would create a fund that would distribute money around the country to promote arts-based approaches to early education. His friend Kevin, a hedge-fund manager, believed this would be good for Matt and helped start the fund. It has since become all-consuming. It is his job. It is what keeps his children alive. It is what keeps him alive. So far, it has distributed more than $430,000 in 48 states.

But he has experienced a terrible weekend. Last week, he was invited to participate in a fund-raiser in Norwalk, Connecticut, and though the event was not a perfect fit, the location, near Stamford, seemed meaningful. It was held in a beautiful mansion. There was wine and cheese and music and people of local prominence. He’d gotten up and told them his story—their story. The event raised $1,200. The amount was pitiful, offensive even. He is devastated by it.

We walk toward Battery Park. It is the anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, and helicopters are flying overhead. He points out various things, including the original battery and the building where he and Madonna were married. He stops to talk to a young man wearing a suit and carrying a sign that reads F*CKED BY THE FED. This goes on for some time. He says he does not know how he feels about the rich. It is the rich who are helping him with his fund.

He’s taken out a cigarette, and, realizing he’s out of matches, he steps over a black lacquered chain and leans down to light his cigarette with the eternal flame adjacent to the 9/11 Memorial. Along Trinity Place, there are young people lying on mattresses, others selling art, hundreds of police officers, some of them on horses. Wall Street is totally barricaded, and he jokes that the Occupiers have picked a poor day to occupy it: Rosh Hashanah. We walk past the statue of a businessman riffling through his briefcase. Construction cranes move far above. He asks aloud whether this might be narcissistic—the foundation, our conversation, all of it. He has been writing a diary on a Facebook page started not long after the fire called Friends Who Love Matt, which has almost 1,000 followers. He was once a successful commercial director, but he has not returned to work. He is running out of money, spending down his personal savings, and redirecting everything he had saved for his daughters’ college education to grow the foundation.

We are sitting on a ledge across from a sushi shop near the Fulton Street subway station. He is chewing Nicorette gum and smoking at the same time. He opens up his MacBook Pro. His cigarette ash flies like dusty snow, landing on his computer screen, where 5 million pixels come together to form what is left of them. Here is Lily. Here is Gracie. Here is Sarah. Here he is in India with Abby two months ago. His friend Kevin had orchestrated a meeting with the Dalai Lama, and here is the Dalai Lama putting his hands around Matt’s head, pressing his head against his. Matt is crying in the photo, he is crying now. Here is where they spread some of the girls’ ashes, a craggy, foggy hill, where, Matt says—and he knows how it will sound—afterward three white dogs came suddenly to sit with them, beautiful, not mangy. Here is Gracie, here is Sarah, here is Lily. Here is all that is left of his family, this past summer in the Rockies, the moon rising over the Columbia River, which flows all the way to the Pacific and into which they’d released more ashes, mingling them with his older brother’s, who fell dead of a heart attack fifteen years ago. He closes his computer, and we walk down the stairs into the station. He says he does not think there will be any more spreading of the ashes that remain.

We are on the train. Across, an old woman is reading Patricia Cornwell. He is looking down. Last weekend was very bad. The grief comes without warning, suddenly, overtaking his body. It is like sucking in seawater. The foundation, he says, is his daughters. If it fails, and now he is practically whispering, quietly crying, sitting in a crowded subway car heading uptown around lunchtime, looking down, fondling a business card, the image of the three of them laughing on one side, the color pink and the lettering of the LilySarahGrace Fund on the other, his hands shaking—

We are heading to an appointment with one of two therapists who are coordinating his treatment. He is sorry, but it was already scheduled, and he is not inclined to cancel it. It will only be 45 minutes. On the sidewalk, a large woman is pushing a stroller with a baby gumming on his fist. We turn another corner, and there are more children playing. We go through the revolving doors into the building, and he says he’ll be back soon. He does not come down from the psychiatrist for more than two hours.

On the day of the funeral, the police closed three lanes of Fifth Avenue. Nearly 1,000 mourners packed St. Thomas Episcopal Church, from celebrities Madonna and Matt had worked with—Calvin Klein, Vera Wang, Philip Seymour Hoffman—to people like Keith Edwards, a 54-year-old from Flatbush who knew the family only via coverage of its destruction and who, the Times reported, reached out to touch Matt as he made his way into the church, telling him, “Brother, I love you.” The story of what happened at 2267 Shippan Avenue—five family members of a prominent New York businesswoman taken all at once in a monstrous fire at a picturesque waterfront Victorian in the early morning hours of Christmas Day—seemed both an immense tragedy and a grotesque allegory: What would you do? How could you go on? What could explain it?

Wreaths and Christmas trees still decorated the soaring French Gothic sanctuary of the church. From eight stories up, small candles hung near the end of each pew. And this was what the Reverend William Shillady wanted them all to know, the girls’ three mahogany caskets before him, each, in the words of the Post, “only slightly larger than the storage boxes we used to put away our holiday decorations”: that God was only good. “Too often, we fall back on simplistic phrases, like ‘It’s God’s will,’ ” Shillady said. “God’s heart was the first to break on Christmas morning.” Madonna and Matt sat next to each other in a front-row pew, flanked on either side by their partners, the scene a fun-house reflection of the time almost a decade ago, after they’d first had Lily, when, overwhelmed, they’d felt compelled to visit and sit in churches at random throughout the city.

Matt has come to see inexorability in everything that has happened to him. So that, as he realized in a group-therapy session several years prior, it was his father’s death of a heart attack when he was 4 that propelled the rest of his life. His mother, devastated, moved Matt and his two older brothers from Concord, Massachusetts, to London, to earn her Ph.D. in childhood psychology. He struggled in middle-class Highgate Village, his dyslexia interpreted as stupidity, his expulsion from boarding school thus foretold. He and his mother moved back to Boston together when he was 16. He graduated from high school in 1982, played in a ska band called Mission Impossible, enrolled in night school at UMass-Boston, became a housepainter, acted out sexually, abused drugs and alcohol, and arrived one night at the hospital with his heart stopped from a heroin overdose. So that he got sober at 25, after following a girlfriend to New York, and began film classes at the New School. So that he ended up being introduced to a woman named Madonna Johnson.

Madonna had arrived in the West Village in the late eighties, establishing herself first as a graphic designer for Esquire and other magazines before joining Calvin Klein’s in-house ad agency. It was the brand’s heyday, and she recognized and stoked the emerging sexualism of the culture, creating the iconic black-and-white Marky Mark underwear campaign. She had left to found her own agency before her 30th birthday. She and Matt fell in love, and she helped foster his career. They bought an apartment off Union Square, which was where Matt’s mother, visiting twelve years ago, abruptly collapsed on the front step. So that, as he stood there watching her die, he felt a pang of mortality, which Madonna felt, too, and both of them, approaching 40, agreed it was time to start a family.

Work became its own self-fulfilling success loop, which had him gone in South Africa when Lily began having anxiety attacks at school at P.S. 3 in the West Village. Specialists determined she was dyslexic, and that she would do better at Windward Academy in Westchester County. The commute was onerous. Matt and Madonna fought over the decision to send the other two girls there when it was determined their reading skills, too, were deficient. Matt’s work took him abroad more often. When he was far from home, he gambled and strayed. She found out. They sat the children down at the table to explain they would have two homes, two birthday parties, two Christmases. In December 2010, Madonna paid $1.725 million for the 3,349-square-foot, five-bedroom, three-and-a-half-bath house at Shippan Avenue, and began commuting into the city. Matt moved into his apartment in Battery Park City. On December 21, 2011, their marriage was officially dissolved.

Two weeks later, he watched as she walked to the altar, glanced at the three caskets, and brushed back her hair. In clear, halting diction, she recalled her “little girl tribe,” her greatest fear that they “would be forgotten.”

She recalled Lily, her firstborn, whom she carried through the city in her BabyBjörn carrier, who sang before she could speak, who constantly made up songs, who was shy and loving. She recalled Sarah and Grace, who were born minutes apart and who called each other “Rara” for the common sounds in their names—Sarah, more gregarious and popular in school, and Grace, fearless, with an earsplitting scream, the first to dive into deep water, who loved bugs and spiders and was curious about everything, who asked Santa for a telescope and microscope she did not live long enough to receive.

Standing before them all, clutching tissues, Madonna recalled instances of her young daughters’ grappling with the concept of death. Grace had asked her repeatedly “if she would die before me. And I told her, ‘No, that is never going to happen.’ But it did, and I wonder, ‘Why?’ ” Once, she had taken Lily to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see an exhibit of Pietà statues. Lily was transfixed by the image of Mary cradling Jesus’ lifeless body. She demanded her mother tell her when she herself would die. Madonna was at first dismissive. Lily lay on the floor. She began crying. She begged her.

“And I told her, after a lot of not knowing what to say, that life is a mystery, and it’s a total mystery, that we will never know when we will die.

“And she accepted that,” she said, “and I did, too.”

The St. Thomas choir sang “Amazing Grace,” and Rufus Wainwright sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from the balcony. Eighteen members of the Stamford Fire Department acted as pallbearers. Punctuating the sea of black were many of the girls’ 200 classmates from Windward, legs dangling in their pews. When it was over, Madonna and Matt followed the three coffins down the long center aisle, her yelps filling the soaring space.

If Matt Badger is right, and all their lives were fated for this, then by the time a six-foot-four-inch military policeman with aqua eyes and a deep southern accent approached Pauline McCarthy’s desk at the base commander’s office at Ernest Harmon Air Force Base in Newfoundland in 1961, it was already well under way. They were, the two of them, hurtling toward tragedy.

Lomer “L.G.” Johnson was born in 1941 in Louisville and raised by a single mother. When he was 17, he went to his father’s new family’s house to ask to borrow money to buy a suit to take a girl to the prom, and when his father said no, he rode the bus across Louisville, won the money in nickel pinball games, and soon thereafter cut off contact with his father. He joined the Air Force, ending up in Newfoundland, where fighter jets escorted bombers flying nuclear weapons over the North Pole, and where he made the acquaintance of Pauline. The second youngest of eight, she’d grown up in Newfoundland in a house with no running water, her father rowing his boat each morning to check on lobster traps. Sent to Montreal for high school, she clandestinely dropped out, adding a year to her birth certificate in order to secure a secretarial job back home. The Cuban Missile Crisis postponed their wedding, but two months later, on Boxing Day, they emerged from a chapel beneath drawn swords, Lomer walking backward in front of Pauline down the snow-cleared path, holding her hand. They had a child and named her Madonna.

After the base was closed, the family moved to Louisville, 2-year-old Madonna and newborn Wade in tow. Lomer began a career in fire safety, first at a gunpowder plant, then at Brown-Forman, maker of Jack Daniel’s and Southern Comfort, where he was eventually named global head of safety and security. He formed in-house fire squads and trained alongside them. He designed a poster contest for employees’ children. (Madonna won first prize for her age group with the image of a fire truck and the slogan “Dial, call fire.”) He helped write federal fire-safety regulations for whiskey distilleries. He became almost obsessed with his work: While his children were watching Saturday-morning cartoons, he was watching videos of buildings on fire. He sometimes thrashed in his sleep, dreaming of fire and other calamities.

Always self-conscious of his country accent—blaming it for missed Air Force promotions—Lomer took his children every Wednesday to a linguistics and diction coach. They were taught to work, Madonna babysitting, Wade a paperboy for the Courier-Journal. They were also taught success. When Lomer’s uncle announced his retirement from his electrical-contracting company, Pauline, his longtime bookkeeper, bought it, becoming the first female electrical contractor in Kentucky; by the time she retired, the company that had once made $700,000 a year was making as much as $15 million. And they were taught, above everything, safety: In the event of fire, the family’s “rally point” was set between the Wilders’ and Judys’ driveways; the children were told they must never go back inside to retrieve others.

The children were expected to achieve, and they did, especially Madonna. Striking, with thick black hair and a small gap between her front teeth, she was a talented artist, homecoming queen, student-council president, and editor of the school newspaper. She attended Vanderbilt University, where she fell in with a population of Northeasterners, spending the summer after her freshman year with friends in the Hamptons. She stayed close with her parents, but never returned to Louisville for more than a week at a time.

Instead, they moved to her. In 2003, the Johnsons retired and moved to Southold, at the tip of Suffolk County, where Madonna and Matt Badger rented them a house across the water from their vacation home on Shelter Island. And when Madonna left for Stamford, they bought a condo in a retirement community in Southbury, Connecticut, an hour north.* Lomer and Pauline traveled constantly to visit family—to Louisville, to Newfoundland, where Pauline built a cottage on her parents’ property. Upon arriving at his children’s houses, Lomer, nine-volt batteries in his pocket, immediately checked their smoke detectors; for Christmas, he gave them fire ladders to store under their beds.

Around strangers, Lomer was reserved, but children were another story. Wade’s daughter, Morgan, rolling around on the floor with him one day, tugged on his white beard, which, after retirement, he had vowed never to shave again. It was a little eureka moment. The following holiday, he applied to malls, and when no one hired him, he bought a Santa suit himself, creating a profile on a website called gigmasters.com. He volunteered, attending a party for a Section 8 apartment complex, taking his granddaughters with him to a nursing home. (Said Sarah, enthusiastically passing out cookies: “Someone better tell the Tooth Fairy that this is where she needs to bring all the teeth, because these people really need them.”) In 2010, he secured a job at a mall an hour from home. He was named Head Santa, riding in the town’s fire truck for Thanksgiving.

And last year, in what he called a dream come true, he beat hundreds of applicants to become Saks Fifth Avenue’s first Santa. Saks’ Claus was instructed not to sit in a chair but rather to walk around the ninth floor interacting with customers; his “Christmas Shop” was designed to suggest “a traditional uptown apartment.” Lomer took the job extremely seriously. He lit the Christmas tree outside the U.N.

On Christmas Eve, his last shift of the year, Pauline drove him into Manhattan. She stayed, watching as the children ran to him and frazzled adults stopped to chuckle when he lumbered past. His knees were bad, and walking around this much aggravated them, but he was ebullient.

*This article has been corrected to show that the Johnsons lived in Southbury, not Southberry.

After the store closed, the Johnsons drove up I-95 to Darien, where Lomer had secured one final private party, near their daughter’s house. He performed for an hour, then offered to stay longer. Outside, Pauline was making calls. She dialed their son, Wade, in Louisville. He’d just left Mass with his girlfriend and her mother, and the three of them were now at the cemetery, visiting the grave sites of his girlfriend’s brother, who’d died five years earlier, and her father, who’d died the year before. She and her mother were crying badly. He reached into his pocket to stop the vibrating without looking, and at that precise moment he thought: I’m so glad to have never had to experience this level of grief. I’m so lucky. Eight hundred miles northeast, his mother was saying this:

“Hi, Wade. It’s Mom. I’m sorry I missed your call earlier … I’m getting in on the 27th around 4 o’clock, and I have a car, so we’ll work out all the details. I’m sitting here outside a house in Darien, Connecticut, and Dad is Santa Claus inside. And he’s just sitting there and flashbulbs are going off everywhere, he’s getting his picture taken, this is his last gig. Give me a call. Talk to you later. Love you very much, and I’ll talk to you if not tonight, I’ll definitely talk to you tomorrow. Okay, love you, bye.”

A few hours later, the Johnsons, who were to celebrate their 49th wedding anniversary the following day, slept in one of the two guest bedrooms on the second floor of 2267 Shippan Avenue. In between them was their granddaughter Grace. Upstairs, in the twins’ turreted room, Sarah and Lily were asleep together. The house was dark and quiet.

As was the Johnsons’ own house, an hour north. Appliances were unplugged; Lomer’s wallet, too cumbersome for his Santa suit, was on top of the refrigerator. On the walls of their bedroom hung four pieces of framed artwork, one by each of their granddaughters. On his side of the bed was Lily’s, which was made back in preschool, when the teacher asked her to draw a message to a family member of her choosing. It was all big circles and stormy swoops of color. When the teacher asked her what message she wanted written on it, she said: “I love you Papa. Don’t leave me behind. See Nana and kiss her. Love, Lily.”

For the previous year, on Shippan Avenue, one decision had begot an outcome which begot another decision which begot another outcome, and so on. Some of the workers, looking back, claimed they could see the ending coming and had tried, in their own ways, to alter it.

Madonna Badger had met Michael Borcina, owner and founder of Tiberias Construction, years earlier, through Alcoholics Anonymous. Tall and broad, with a shaved head and strong facial features, he’d been a fine carpenter for many years, trained in the German style, whereby things like mantels and moldings were made from scratch. He now specialized in residential renovations. She brought him to the Victorian at 2267 Shippan Avenue to solicit his opinion before she bought it. He’d seen the same issues and the same potential—the layout needed to be opened up, the aluminum siding replaced, kitchen and bathrooms updated. She decided to hire him as general contractor. Borcina had allowed his Connecticut state contractor’s license to expire rather than pay the judgments against him, totaling $100,000, from multiple lawsuits alleging incomplete, inadequate, or unnecessary construction; he circumvented this by filing under the license of a friend.

Demolition began in early 2011. The work was expected to be done by summer. Initially, Madonna and the children lived in a rental property in Stamford. Borcina established an office at the property’s detached three-car garage, calling in workers he knew, advertising for others on Monster.com, conducting interviews on site. As a boss, he proved mercurial. The project itself quickly spiraled. Opened walls exposed new problems. A new electrical system would be required. Workers came and went, sometimes hired and fired in the same day.

The workers questioned Borcina’s fitness as a general contractor. Don Raskopf, who worked as the carpentry foreman from August to November, and Andrew Grunow, an experienced contractor who worked as a master carpenter during the same period, were discomfited by some of his decisions, including his plan to renovate the interior even while exterior work was incomplete. Scaffolding was erected, so as to remove the aluminum siding; the project remained largely unfinished. Insulation and drywall were damaged by rain. Active leaks formed in the dining room, living room, master bedroom, and mudroom.

Grunow, a former Sound Beach volunteer fireman, was particularly concerned about safety. He later claimed he took it upon himself to install fire extinguishers and battery-operated smoke and carbon-monoxide alarms throughout the house prior to an insurance-company inspection that he knew Borcina would fail. (He claimed, as well, that Borcina ordered them taken down because of false alarms once the sanding of the walls and painting began in earnest.) He said he repeatedly tried to warn Borcina that he was creating an excessive “fire fuel load,” citing the amount of wood being used—for columns, beams, cabinetry, moldings, oil-finished flooring, and paneling in the kitchen, mudroom, and up the butler’s staircase, which Grunow warned was already narrower than building codes allowed. Borcina made clear his uninterest in any criticism, once forcing Grunow to write a letter of apology, promising he would work according to Borcina’s precise specifications and not offer alternative opinions.

Behind Borcina’s back, the workers talked about their boss. They were convinced that he was “chasing” Madonna. (Despite maintaining a $3,900 apartment in Battery Park City, he chose often to stay in her garage, and one employee was upbraided by Borcina after having informed Madonna, when she asked, that Borcina was on vacation in Puerto Rico with his girlfriend.) They attributed some of his idiosyncratic characteristics—his fickleness, his constantly being cold, his poor memory, his deafness in one ear and ferocious speaking voice—to lingering side effects from surgery several years ago to remove a brain tumor.

When Madonna’s rental expired, around the beginning of the summer, the project was far from done. She had a large Gulfstream trailer parked on the property, into which she moved the family for about a month. The arrangement proved difficult. The girls spent part of that summer with their father. In the meantime, Borcina was to focus on the third floor, the girls’ floor, so the family could return in time for the school year.

When the Badgers moved into the house, on September 9, much was still unfinished, including parts of the third floor, to which extension cords snaked up the staircase. As the new kitchen was still going up around her, Madonna and her two nannies used a toaster oven, coffeemaker, and a microwave plugged into a power strip plugged into a temporary outlet on the kitchen counter to the right of the stove. Floors needed to be laid; closets and cabinetry built; radiant heating put down in the bathroom floors; recessed lighting, valances, a dining-room chandelier installed. Grunow and Raskopf told investigators that when they left the job, in November, the top sashes on the old double-hung windows on the third floor were painted shut from years of accumulation, while the lower sashes had been secured with screws and sticks because the sash locks had been removed.

Madonna had also hired Borcina to handle renovations of her Manhattan office, and there were complications from that job, too. Workers heard heated financial conversations between Borcina and Madonna, leaving her “bawling.” They felt certain he was padding the bills, ordering construction redone where they thought it was unnecessary. Like others close to her, they wondered, too, about Madonna—why she chose to continue pursuing a relationship with Borcina professionally, let alone personally (by November, they had become a couple). Those who know her attributed it to her constitution, to the same things that made her so successful: her steadfastness, her determination, her belief in her own good judgment.

On December 23, the walls of the mudroom were sanded; an alcohol-based primer was used to coat the raw-wood paneling. Painters were working their way through the house. On the morning of the 24th, they were expected back. It was Christmas Eve, and Madonna decided to call them off.

The mudroom blazed. Soot particles burst, glowed, alighted. Fire and smoke rose in a plume to the less-dense atmosphere above, swirling within the small confines and back into itself. Within minutes, the increasing temperature drove every object to its ignition point, including he remaining Duraflame fire-starters. Flames opened to the outside, to a steady flow of oxygen. The smoke and heat and gases moved inward, streaming like water round the top of the mudroom entryway. The air mass itself finally ignited. Flames accelerated across the floors and up the butler’s stairwell to the landing, across the kitchen and dining room and then out across the open first floor.

Madonna opened her eyes. She immediately began choking. The room was dark and filled with thick smoke. The pocket doors were awash in flames. She heard no alarms, no other noise. She could not make it through the smoke toward the doors. Instead, she opened a window along the house’s front exterior. As she did, the smoke rushed across the room. In her nightgown, she climbed onto the flat roof of the front porch, which wrapped around the house. She shrieked. She scrambled around the porch. She looked up to the top-floor window of her neighbors’ house. Beyond the reflection of the horrific orange light, she could see her neighbors, Steve and Fern Loeb, whose 8-year-old son played often with the girls. She shouted about her children, to call 911. She climbed the construction scaffolding to the third floor, then up the turret. She could not see inside, there was too much smoke and fire. She began kicking against the window. She kept screaming their names.

The members of Engine 4 were returning from a house nearby where a woman had sought help after hearing an alarm coming from somewhere in her house; they had discovered the source was a wrapped gift. They arrived at Shippan Avenue at 4:52 a.m. There she was, climbing the scaffolding, as the fire spilled monstrously over the lip of the rear third floor. A second alarm was sounded.

In the rear guest bedroom, Borcina heard a knock, his bedroom door may have swung open. Smoke was pouring in. He could not see but sensed a presence he believed was Lomer and Pauline with one of the children. He walked into the smoke. He fell over. He went to a window, opened it, inhaled deeply, shouted behind him in the dark, “Come this way!” No one followed. He made his way into the hallway, where smoke was gushing up the main stairwell. He started down the steps, toward the front door. It was on fire. The air above him singed the skin of his shaved head, forcing him to crouch down. He scrambled back to his room. There was no one behind him. He climbed out the window, falling to the ground in his boxer shorts.

It became ravenous. The sound was deafening. The stainless steel of the refrigerator began discoloring; inside, the food burned.

Down the street, firefighters struggled to secure the hose line to a hydrant. Other firefighters scattered about the home’s exterior, one to the roof to control the spraying, another atop a large apparatus that had been driven onto the property, directing streams of water into the windows. More firefighters tried to make entries onto all floors, those from Engine 4 crawling inside the turreted room to enter the master bedroom, blinded by smoke and darkness, sweeping a piece of metal across the floor in front of them in search of life. Others entered Madonna’s room through the second-floor windows; the structure was collapsing, the ceiling falling in huge chunks, and by now the pocket doors were gone. There was a view through to the landing, through the flames and smoke, there were two people—an adult, a child? The firefighters would later explain the house was “fully involved,” it was too late, the victims could not “be viable.”

At 5:26, a captain made the call for all those inside the building to back out and for all those attempting to enter the building to stop.

What remained of the house sat up on a high foundation atop a mostly intact though completely flooded basement. There was still a tall wraparound porch with a low-slung white railing strung with Christmas lights. There was a swing and some rocking chairs on the part of the turret that on the first floor became a covered portico. Inside there were gaping holes and tunnels. Hours later, as the sun rose over the Long Island Sound, the firefighters entered one such tunnel, walking atop ladders they laid down as makeshift joists and floor beams. In the rear of the turreted room, beyond the window her mother had been kicking at, they found remains later identified as Sarah Badger. On the second-floor hallway landing they discovered those of Pauline Johnson and Grace Badger; Pauline had taken off her nightclothes, swaddling her granddaughter. In one of the spare bedrooms on that floor, out a different window, lying atop beams meant to replace the flat roof of the sunroom below, they found the body of Lomer Johnson. He’d evidently thrust himself against the plywood obstructing that window and fallen through it, breaking his neck. Just inside the window, on top of stacked-up books, was the body of Lily Badger.

They—we—groped for explanation. For cause and effect. For some reason why it could not happen to any of us.

Which is to say, the story became about smoke detectors.

In some places around southeastern Connecticut, smoke-detector sales increased 700 percent. On January 6, 2012, the Stamford Advocate quoted Ray Barrett, general manager of Keough’s Hardware and Paint, who said the store had sold two months’ worth since the fire. The paper noted that the “fervor for smoke alarms appears to wane with distance,” with three hardware stores in New York State and six in the Johnsons’ native Louisville reporting “no difference.” “You have to have your own fire,” certified fire-protection specialist Daniel Gardiner told the paper. “And your own deaths.”

Officials pursued the same angle.

Stamford’s chief building inspector and fire marshal’s conclusion was straightforward: The origination point appeared to be the mudroom, where the ashes had been disposed; the only area of the basement showing any sign of fire damage was the ceiling area in the northwest corner, directly below the rear entryway into the house from the mudroom. In the basement, they inspected a “metal box that appeared to contain the main electronics for a security/fire detection system. The internal components did not appear to have suffered any damage due to the fire, but it was noted that the main power supply (plug) was still inside the metal box and not connected to a permanent power supply. There was also a DC battery inside the metal box that was not connected to the main circuit board.”

Connecticut State attorney David I. Cohen spent six months investigating. “When such a horrific event occurs, it is only natural that those related to the victims and the public in general want to hold someone responsible for what is otherwise an inexplicable accident,” he wrote in his report. Cohen did not question the official narrative—that the fire began in the mudroom—but he noted that we will never know whether the battery-powered detectors temporarily installed over the summer were still active, as Borcina claims. The day after the fire, Stamford officials decided to tear down the burned-out structure, citing a safety risk to anyone who might enter it. “Where so much is unknown or in dispute,” Cohen wrote, “where the facts are inconclusive and where the safety of the public will not be enhanced, I have decided to exercise the discretion given to me by our State Constitution and by my oath of office and decline, at this time, to prosecute.”

Madonna maintains her own version of how and why. She does not believe the official cause of the fire. She is certain it had something to do with the sparks she saw shooting from the electrical box at the rear of the house as she ran back and forth on the porch roof that night. She says Stamford investigators latched onto the mudroom after confronting her before she even knew the fate of her family to ask what she thought might have caused the fire, and all she could think of was the embers. She has photographs of the house she says show smoke detectors hung all over, and she cannot explain why they did not go off that morning, why she awoke to a smoky silence. She is incredulous that anyone who knows her, or especially her father, would believe they would have allowed anyone to be in the house without them.

She has surrounded herself with a small circle of close friends largely from her professional life, whom she’d first contacted last Christmas morning from her bed in the emergency room. Her business is still running, though she has been living far away from it, in Little Rock, Arkansas. She has spoken one time publicly about the events, with Matt Lauer this past summer. He asked about the current nature of her relationship with Borcina, who is apparently living back in his apartment in Battery Park City:

MADONNA BADGER: Hm.

MATT LAUER: I know friends of yours, or some people in your life, have asked you how you could still have a relationship with him, how you could be near him, quite frankly.

BADGER: Mm-hmm. Right.

LAUER: How do you answer that question?

BADGER: The answer for me is that we were in the fire together. We were in the fire. And we spent the last night on Earth with my three children and my mom and dad, and it was beautiful.

She blames the city of Stamford. She has filed a lawsuit against its officials, alleging their actions in tearing down her house without notifying her destroyed any possibility of a second opinion. She spent a week in an acute-care unit after coming close to attempting suicide.

Matt has sympathy for his ex-wife. He has sympathy even for Borcina. He encountered him in lower Manhattan not so long ago, and Borcina appeared to be struggling. He asked Matt if he could hug him. Yes, Matt has sympathy. No, Borcina could not hug him.

Matt has filed suit against Borcina for a pattern of incompetence and negligent building practices—were it not for Borcina, the suit contends, his children would still be alive. He’s named the City of Stamford as co-defendant, for the premature teardown and inadequate building inspection. He has not sued Madonna. He believes she is suffering enough.

He tries not to think of the lawsuit, to spend every waking moment focused on the foundation. A few days after his disappointing fund-raiser in Norwalk, he drives there, for an audience that has been arranged for him with Connecticut state senator Bob Duff, who Matt hopes can help. They sit in a conference room in City Hall. Matt’s words come slowly, carefully. Frequently he stammers. He tells the senator he is here to discuss the fund’s commitment to Norwalk and vice versa. He says that while the event last week was beautiful, its outcome—$1,200—was disappointing.

The senator tells Matt he disagrees. He says $1,200 is hardly insignificant. He advises Matt that his foundation is new, there are many causes potential donors can support, that his family, for instance, supports the Norwalk Symphony. There is, what’s more, the issue of “how people can get their arms around this.” He says, quite frankly, it is also the nature of it all. For him, personally, it was “very difficult, very emotional.” He has small boys, and “it was hard for me as a dad.” He notes the fire took place just two towns over. “This,” he says again, “has been very hard for us.”

Matt grows increasingly flustered. He explains he needs to raise $20,000 to make the relationship worthwhile. Duff says he doesn’t have twenty people in his Rolodex that he can just call up. He jokes he is a Democrat. Matt is all but pleading. He reiterates that there were 200 people who attended the fund-raiser, and that they raised $1,200. He wants to know if the senator knows what this feels like:

“I put my three daughters out there. And this is what they’re worth?”

Every day—every minute, every second—can fall apart. Back in New York, on a beautiful early-autumn evening, Matt and I are walking through Soho. He is in good spirits, having just discussed his plans for a cross-country road trip to visit the schools that have received funds from the foundation. We are making our way toward the restaurant La Esquina. He is smiling and occasionally joking, and he explains that there are ways in which this talking feels therapeutic. It’s not like he can drink, he says. He cannot go to his mate’s and just drink. His voice changes.

The thing is, he says, he did all the things. He’d worked hard. He’d changed. He’d tried. He’d shown up for his life, for his kids. And yes, there were things he’d fucked up. Yes, he may even have fucked up his marriage. But, he wants to know, is that any reason to take away his kids?

A tattooed man with one pant leg rolled up slows his bike approaching Grand Street. Warm light glows from a shop window, through which a woman fingers a spatula. Two women in sundresses and high heels pass by. Matt has stopped walking. He is looking at me. He wants me to know he knows they woke up. He knows, from the positions of their bodies, they woke up. They were scared. And they were running around the burning house.

A breeze picks up. There are the sounds of downtown New York City at six o’clock on a warm late-September evening when Matt Badger tells me he knows his children “melted—

“They fucking melted.”

He wants to know why.

Additional reporting by Emma Whitford.