Here’s one dirty little secret about the revelations of domestic spying at the National Security Agency: Had Edward Snowden not embarked on a madcap escape that mashed up plot elements from Catch Me If You Can, The Fugitive, the O.J. Bronco chase, and “Where in the World Is Matt Lauer?,” the story would be over. The leaker’s flight path, with the Feds and the press in farcical flat-footed pursuit, captured far more of the public’s attention than the substance of his leaks. That’s not his fault. The public was not much interested in the leaks in the first place. It was already moving on to Paula Deen.

At first blush, the NSA story seemed like a bigger deal. The early June scoops in the Guardian and the Washington Post were hailed universally as “bombshells” and “blockbusters” by the networks. America’s right and left flanks were unified in hyperventilating about their significance: Rand Paul and The Nation, Glenn Beck and Michael Moore, Rush Limbaugh and the Times editorial page all agreed that President Obama had presided over an extraordinary abuse of executive power. But even as Daniel Ellsberg hailed the second coming of the Pentagon Papers, the public was not marching behind him or anyone else. The NSA scandal didn’t even burn bright enough to earn the distinction of a “-gate” suffix. Though Americans were being told in no uncertain terms that their government was spying on them, it quickly became evident that, for all the tumult in the media-political Establishment, many just didn’t give a damn.

Only 36 percent of the country felt that government snooping had “gone too far,” according to CBS News. A Pew–Washington Post survey found that 62 percent (including 69 percent of Democrats) deemed fighting terrorism a higher priority than protecting privacy. Most telling was a National Journal survey conducted days before the NSA stories broke: Some 85 percent of Americans assumed that their “communications history, like phone calls, e-mails, and Internet use,” was “available for businesses, government, individuals, and other groups to access” without their consent. No wonder the bombshell landed with a thud, rather than as a shock. What was the news except that a 29-year-old high-school dropout was making monkeys of the authorities with a bravado to rival Clyde Barrow?

An ACLU official argued that the so-what poll numbers were misleading: “If terrorism was left out, it would change the polling results dramatically.” In other words, blame the public’s passivity on the post-9/11 cultural signposts of 24 and Homeland, which have inured Americans to a bipartisan Patriot Act regimen in which a ticking terrorist time bomb always trumps the Constitution. Obama, a Homeland fan himself, hit the point hard to deflect criticism. “You can’t have 100 percent security and also then have 100 percent privacy and zero inconvenience,” he said when alluding to the terrorist plots NSA spying had disrupted. “We’re going to have to make some choices as a society.”

The virtue of this rationale is that it casts not just the domestic eavesdroppers in a patriotic light but also the citizenry that valiantly sacrifices its Fourth Amendment rights to the greater good of stopping the evildoers. But that’s letting everyone off easy and is hardly the whole story of the choices Americans have made “as a society”—and that were made before Obama or, for that matter, George W. Bush took office. Many of those choices predate 9/11 and have nothing to do with fighting terrorism at all.

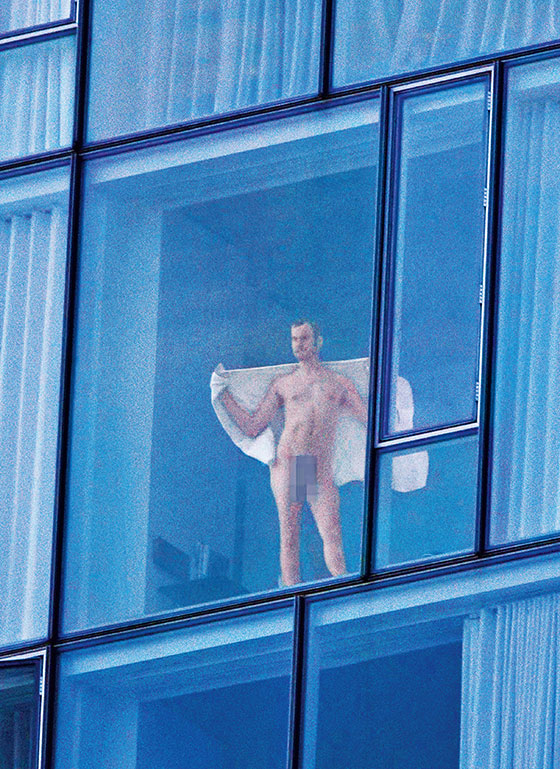

The truth is that privacy jumped the shark in America long ago. Many of us not only don’t care about having our privacy invaded but surrender more and more of our personal data, family secrets, and intimate yearnings with open eyes and full hearts to anyone who asks and many who don’t, from the servers of Fortune 500 corporations to the casting directors of reality-television shows to our 1.1 billion potential friends on Facebook. Indeed, there’s a considerable constituency in this country—always present and now arguably larger than ever—that’s begging for its privacy to be invaded and, God willing, to be exposed in every gory detail before the largest audience possible. We don’t like the government to be watching as well—many Americans don’t like government, period—but most of us are willing to give such surveillance a pass rather than forsake the pleasures and rewards of self-exposure, convenience, and consumerism.

R.I.P. the contemplative America of Thoreau and of Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, who “would prefer not to”; this is the America that prefers to be out there, prizing networking, exhibitionism, and fame more than privacy, introspection, and solitude. And while it would be uplifting to believe that Americans are willing to sacrifice privacy for the sole good of foiling Al Qaeda, that’s hardly the case. Other motives include such quotidian imperatives as shopping, hooking up, seeking instant entertainment and information, and finding the fastest car route—not to mention being liked (or at least “liked”) and followed by as many friends (or “friends”) and strangers as possible, whether online or on basic cable. In a society where economic advancement is stagnant for all but those at the top, a public profile is the one democratic currency most everyone can still afford and aspire to—an indicator of status, not something to be embarrassed about. According to the Pew-Post poll, a majority of Americans under 50 paid little attention to the NSA story at all, perhaps because they found the very notion of fearing a privacy breach anachronistic. After the news of the agency’s PRISM program broke, National Donut Day received more American Google searches than PRISM. There has been no wholesale (or piecemeal) exodus of Americans from Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Skype, or any of the other information-vacuuming enterprises reported to have, in some murky fashion, siphoned data—meta, big, or otherwise—to the NSA. Wall Street is betting this will hold. A blogger on the investment website Motley Fool noticed that on the day PRISM was unmasked, share prices for all the implicated corporate participants went up.

If one wanted to identify the turning point when privacy stopped being a prized commodity in America, a good place to start would be with television and just before the turn of the century. The cultural revolution in programming that was cemented by the year 2000 presaged the devaluation of privacy that would explode with the arrival of Facebook and its peers a few years later.

What we now call reality television had been around since the dawn of the medium. Allen Funt’s Candid Camera had its television debut in 1948 (and had been on radio before that as “Candid Microphone”). But the everyday Americans spied on in Funt’s wholesome Peeping Tom pranks were caught by surprise; they didn’t volunteer for public exposure. The twelve-hour 1973 PBS mini-series An American Family (supported by funding from the Ford Foundation, no less) was a breakthrough because the troubled Louds of Santa Barbara willingly submitted to parading their travails in close-up on-camera. By the time MTV unveiled its series The Real World in 1992, the advent of video, digitalization, and compact cameras had made projects emulating An American Family much easier to produce in quantity and at greater length.

The Real World began as a somewhat earnest docu-soap of multicultural American youth wrestling with Real Issues. But by the end of the decade, sex and alcohol were being stirred profusely into the mix. In 2000, CBS took the genre a step further by airing an American adaptation of a Dutch television hit, Big Brother, in which occupants of a quarantined house are captured on camera 24/7, bathroom visits included, for three months as the participants are voted out one by one. Sure enough, the coinage Big Brother would soon become unmoored from George Orwell’s vision of totalitarian terror and become known as the brand of a cheesy entertainment franchise hosted by Julie Chen. As it happened, Big Brother’s second-season contestants were isolated in their San Fernando Valley barracks on 9/11, and one of those contestants was the cousin of a missing Aon worker on the 90th floor of World Trade Center 2. After some debate over whether the house’s inmates should even be told the news in real time, which would be a violation of the show’s lab-rat rules, the young woman with a familial stake in the attacks was filled in. She chose to remain on-camera with her surrogate reality-television family (and audience) rather than return to her real family in New York, which was still waiting to learn that her cousin was dead.

Big Brother began its fifteenth season last week. We now know that it was merely a harbinger of what was to come. In 2000, it and Survivor (also on CBS) were novelties. In 2013, more than 300 reality shows are airing on a profusion of networks, including some that have revised their identities to accommodate them. (History, formerly known as the History Channel, is home to Ax Men and Swamp People.) That count does not include YouTube, where home productions can rival the biggest TV reality hits in audience. The 2011 video of 6-year-old Lily Clem’s reaction to her birthday present, a trip to Disneyland, attracted 5 million viewers in just its first three weeks.

Reality television is not a showbiz fad but a national pastime whose participants are as diverse as America in terms of class, race, creed, and ethnicity. If redneck subjects are now the rage—Here Comes Honey Boo Boo outdrew Fox News coverage of the GOP convention in the prime 18-49 demographic—the desperate urban middle class is at the heart of shows like the Vegas-based smash Pawn Stars (another History hit). Though some participants cash in—the Robertson brood of Duck Dynasty has transformed an already prosperous rural Louisiana business selling duck calls into a multi-platform entertainment empire—money isn’t the only motive. Many reality-show performers receive nominal pay, and the workplace protections afforded to union members usually don’t apply. The Kardashians notwithstanding, the payoff in fame also can be slight, not even fifteen minutes’ worth on the lower-rated shows. More often, exhibitionism is its own reward. Many Americans simply want to be seen, even in financial or psychological extremis, by as many of their fellow citizens as possible. That the government may also be watching—whether in pursuit of terrorism, ordinary criminality, immigration violations, employee malfeasance, tax evasion, or whatever—seems no deterrent.

The same risk of surveillance is taken by the many more Americans who bare their lives online, trading off privacy for speedier transactions, self-expression, and self-indulgence. With the notable exception of Anthony Weiner, few are naïve about that bargain. It’s no surprise that 85 percent of the country thinks it is being snooped on: Uncannily precise recommendations of products, friends, and followers stalk our every keystroke on the web. Given that Facebook’s members are more than three times as numerous as the American population, all of them linked to multiple networks that often have little or nothing to do with friendship, it’s a no-brainer that the infinity of data will be trolled by outsiders, whether flesh-and-blood or algorithmic, and whether the motive be investigative, prurient, mercantile, masturbatory, altruistic, or criminal. And that trolling is so easy! As Evgeny Morozov has written in The Net Delusion, the 2006 German film The Lives of Others is a potent reminder of “how costly surveillance used to be” for a totalitarian state in the Cold War era: “Recording tape had to be bought, stored, and processed; bugs had to be installed one by one; Stasi officers had to spend days and nights on end glued to their headphones, waiting for their subjects to launch into an antigovernment tirade or inadvertently disclose other members of their network.” Ah, the good old days of government surveillance, when the spies had to jump through exhausting hoops to do their dirty work.

Whatever the fine points of the NSA’s snooping, anyone who cared could surmise enough of the big picture to be wary long before the Snowden leaks filled in graphic details. The NSA is crying wolf when it claims that his disclosures are an enormous boon to terrorists, unless you believe terrorists are morons. There have been NSA leakers before Snowden, and they provided plenty of connectable dots. A remarkable two-year Washington Post investigation published in 2010 found that as of then, some 854,000 Americans had top-secret clearances—nearly one and a half times the population of the nation’s capital. Nearly a third were private contractors like Snowden. The Post also discovered that after 2001, intelligence agencies began building 33 new facilities in the Washington area alone, with a total square footage (17 million) almost equal to three times that of the Pentagon. What could all these people possibly be up to? What was all that space needed for?

In March 2012, James Bamford, for three decades the most authoritative journalist on the NSA beat, provided answers in a Wired cover story prompted by a clandestine $2 billion NSA data center under construction in Utah. “Flowing through its servers and routers and stored in near-bottomless databases will be all forms of communication, including the complete contents of private e-mails, cell-phone calls, and Google searches, as well as all sorts of personal data trails—parking receipts, travel itineraries, bookstore purchases, and other digital ‘pocket litter,’ ” Bamford reported. Why? “The NSA has turned its surveillance apparatus on the U.S. and its citizens.”

In fact, the prolific public clues about the NSA’s intent also predate 9/11. In the Jerry Bruckheimer–Tony Scott movie Enemy of the State (1998), a fictional retired NSA officer played by Gene Hackman says, “The government’s been in bed with the entire telecommunications business since the forties. They have infected everything. They can get into your bank statements, computer files, e-mail, listen to your phone calls.” The NSA’s then-director, Michael Hayden, was so concerned about this fictional leak that he tried to mount a PR offensive to counter it. Just a few months after that film’s release, Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy in essence confirmed it with his own famous dictum: “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”

And so we did learn to stop worrying and love the promiscuous use of Big Data by business and government. Mark Zuckerberg was telling the truth, even if to serve his own interests, when in 2010 he explained his rationale for the constant, incremental loosening of Facebook’s dense and ever-changing privacy policies: “People have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people.” The Snowden leaks show that Facebook and PRISM had aligned six months earlier, and in 2010, as the Times recently discovered, the keeper of Facebook’s secrets, its chief security officer, Max Kelly, defected to the NSA. But even as early as 2008, an internal memo at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services had recommended that the agency’s fraud office start exploiting social networks as an “excellent vantage point” for observing “the daily life of beneficiaries and petitioners” suspected of wrongdoing. The memo—cited by the public-interest lawyer Lori Andrews in her book I Know Who You Are and I Saw What You Did—was nothing if not prescient. Facebook was a gift to surveillance that would keep on giving, it argued, because the “narcissistic tendencies in many people fuels a need to have a large group of ‘friends.’ ”

In the aftermath of the Snowden leaks, those who want to shut down dubious NSA programs have been hard pressed to come up with ways of getting that done. The ACLU is suing, and so are Rand Paul and Larry Klayman, the right-wing activist known for his quixotic legal battles against Bill Clinton in the nineties. Commentators at The New Yorker and The New Republic are calling for a national commission. Dianne Feinstein, the chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee and a fierce NSA defender, has proposed monthly hearings, presumably to bore the country into inertia. No doubt the Obama administration will toss out a few crumbs of transparency to satisfy its liberal base, but neither the president nor his party’s leaders, exemplified by Feinstein, Harry Reid, and Nancy Pelosi, want change from the status quo. Neither would Hillary Clinton. The same is true of Republican leaders, despite their professed loathing of big-government overreach in Obamacare and at the IRS. That leaves Paul on the Republican side and the two Democratic Senate apostates, Mark Udall and Ron Wyden, who have been on the NSA’s case for years. They have about as much of a chance of bringing change in 2013 as the former senator Russ Feingold did in his lonely opposition to the Patriot Act in 2001. Little short of a leak stating that the NSA is tracking gun ownership is likely to kindle public outrage.

Of course, there are some steps that ordinary Americans can take to cover their daily digital tracks and limit their vulnerability to snooping of all kinds. But there aren’t many. In their new book, Big Data, Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Kenneth Cukier observe that “in the era of big data, the three core strategies long used to ensure privacy—individual notice and consent, opting out, and anonymization—have lost much of their effectiveness.” Their proposed workarounds are laudable—why not have “new principles by which we govern ourselves”?—but not exactly an action plan. Andrews calls for a new “Social Network Constitution” but for the short term points out that citizens of Facebook, the third-biggest nation in the world as measured by population, have “little recourse other than to leave the service.” This would require asceticism on a mass scale unknown to modern America.

The easiest individual solutions for trying to protect one’s privacy are the obvious ones. Quit social networks. Stop using a cell phone. Pay for everything in cash (but stop using ATMs). Abandon all Google apps, Amazon, eBay, Netflix, Apple’s iTunes store, E-ZPass, GPS, and Skype. Encrypt your e-mail (which will require persuading your correspondents to encrypt, too). Filter (and handcuff) your web browser with anti-tracking software like Tor. Stop posting to YouTube and stop tweeting. As Big Data elucidates: “Twitter messages are limited to a sparse 140 characters, but the metadata—that is, the ‘information about information’—associated with each tweet is rich. It includes 33 discrete items.”

So vast a cultural sea change is beyond today’s politics; it would require a national personality transplant. What the future is most likely to bring instead is more of the same: an ever-larger embrace of ever-more-brilliant toys and services that invite more prying from strangers, corporations, and government. No sooner had Snowden’s leaks landed than Instagram, owned by Facebook, announced a new mobile service enabling its users to post their own brief reality-television-style video nuggets much as the equivalent Twitter service, Vine, already does. Soon to ship from Microsoft is a new Xbox game console requiring a device called Kinect, which, besides monitoring bodily motions, listens to users even when the console is turned off. It’s unlikely that fanboys (and girls) will shun the new Xbox any more than they will disdain the intrusiveness of the much-awaited Google Glass. If anything, they’ll fight to be first in line.

Civil libertarians can protest about how the government will track us on these devices, too, but as long as the public and the political Establishment of both parties remain indifferent, the prospect of substantial change is nil. The debate would be more honest, at least, if we acknowledge our own responsibility for our “choices as a society.” Those who complain about the loss of privacy have an obligation to examine their own collaboration, whether by intent or apathy, in the decline and fall of the very concept of privacy. We can blame terrorists for many things that have happened since 9/11, but too many Americans cavalierly spilling TMI on too many porous public platforms is not one of them.