Not long ago, Yagiken Co., an Osaka-based manufacturer of traditional Japanese Buddhist altars (known as butsudan) for home-based ancestor worship (known as kuyo), opened a showroom called Gallery Memoria on West 26th Street. Brochures declare, “Kuyo; always stay connected to the loved ones you’ve lost.” It’s operated by Nana Onishi, an artist whose work appeared in the 2001 Venice Biennale, who compares the altars to sushi: “You have California rolls here, but they weren’t invented in Japan.” In the same way, she says, Americans can take what aspects they like from kuyo and adapt the concept to fit their lifestyles and preferences. In order to get people thinking, Onishi’s organizing a show at Gallery Memoria in which international artists will create work depicting “how they would express their own form of kuyo.”

In Japan, butsudan often contain a consecrated tablet with the names of the deceased members of the family, as well as a statue of the Buddha. Family members often kneel or stand in front of the butsudan and pray to their ancestors. It can be a daily practice to leave offerings to ancestors, such as hot tea, rice, or even cigarettes—anything the person liked in life. Well, within limits. “You wouldn’t put wine coolers,” Onishi says.

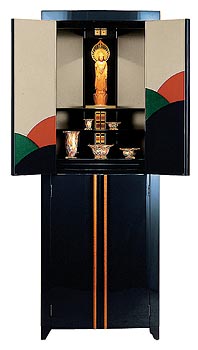

It’s a tradition in decline: According to Yagiken research, about 30 million Japanese households own butsudan. But the owners tend to be elderly. Yagiken is hoping to reinvigorate the market by offering younger Japanese couples sleeker, more contemporary altar styles. At the gallery, kuyo stages fill the room, and “kuyo accessories” like bud vases, tiny cups, and incense holders are arranged on shelves. The stages, polished to a shine and made from teak or bamboo, range from about $2,000 (for tabletop models that look like music boxes) to $36,600 (for a blue-and-green lacquerware piece the size of an armoire). There are also tiny wooden stages that resemble photo frames and cost about $250.

Riverdale resident Masako Hashimoto, 37, recently bought a butsudan—the compact Pixy model that came with a bud vase and candle—at Gallery Memoria. Her father’s recent death moved her to reflect on the custom of ancestor worship. “I thought maybe I need a nice place for my father where he could rest in peace, a place where I could remember him and talk to him.” Standing in her apartment, clutching a photograph of her dad, she considered creating a kuyo space for him on her bookshelf, but it “looked like a temporary setup.” When she went to Memoria, “I thought, This is a nice idea. I don’t have to go the old-school traditional way. I can do this my way.” But even given the popularity of Zen-like affectations here—from yoga to the lobbies of W hotels—kuyo could be a hard sell. Helen Hardacre, a Harvard professor of Japanese religions and society, points out that despite Yagiken’s attempts to Westernize Japanese ancestor worship by festooning it with crucifixes, “the idea of praying to the dead is distinctly heretical to Christians.” Next: A 100-Person Poll on the Lebanon-Israel Conflict

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.