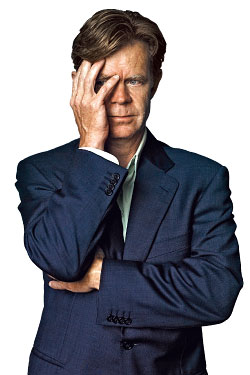

William H. Macy’s dresser, Laura Beattie, has an urgent message: “I think I’ve finally figured out what to do about your socks.” The curtain has just fallen on the Wednesday matinee of Speed-the-Plow, and Beattie is almost breathless as she helps Macy out of his character Bobby Gould’s movie-executive jacket. He’s had to make many adjustments since answering the call of his friend David Mamet to fill the role vacated by Jeremy Piven, the notorious sufferer of mercury poisoning by sushi. But despite the two weeks he had to prepare for his first theater role in eight years, and the tendency of his 58-year-old memory to sometimes spew out “word burgers” onstage, Macy’s biggest problem with moving to Broadway from the Hollywood Hills is temperature control. In other words, cold feet.

It’s been a constant battle keeping the actor warm, Beattie says, and he’d rather not perform barefoot, as called for in scene two. But the socks from the first scene don’t match the pj’s for the second or the suit for the third, and there’s no time to change. Today, out of desperation, Macy wore the same dark socks in every scene. Which, he now realizes, was a mistake. “Our costume designer would have committed seppuku if she’d seen it!” He and Beattie agree to layer socks and peel them off during the show. Then he gets some hot tea.

Macy is only with Plow through February 22. For a while, the sign on his door read new guy, he says, “because there are so many that have been going through here”—Piven, then, over the past six weeks, Jordan Lage, Norbert Leo Butz, and Macy. Each new guy has had the privilege of occupying the one dressing room with a shower, which also happens to have been Marlon Brando’s room for Streetcar. But none has had a chance to add homey touches like Elisabeth Moss’s string of Christmas lights or Raúl Esparza’s wet bar. Macy’s countertop reveals some Old Spice deodorant (“to be kind to my dresser”) and a Motorola Razr labeled BILL (“My wife [Felicity Huffman] has the exact same phone”). The walls show the only sign of life: pictures he took of his daughters, Sophia, 8, and Georgia, 6. Macy packed in such a hurry that he forgot photos of “Flicka” (Huffman), who replaced Madonna in the original 1988 production (“so we’re both replacements,” he says). But he’s tacked a note from her on his mirror: “Fuck them! Have fun—you’re the best. Shut the door!” (“That’s from the French je t’adore,” he says. “It became ‘shut the door’ at some point.”)

The girls are coming to visit soon, and Macy takes me to every spot from which he wants them to see the show, ending up backstage, among the fly cables. “You know why you can’t whistle onstage?” he asks. “Because in the old theaters, all the rigging was done by sailors, and they signaled by whistling, so it became bad luck to whistle onstage. It could be a false signal. Somebody could drop a sandbag on you!” (Later, I hear Macy whistling while he pees. He blushes and says that the only theater superstition he believes in is the one about the Scottish play.)

Before the evening show, Macy will take a nap and do some vocal warm-ups taught to him by none other than Byrne Piven—Jeremy’s dad. “I babysat Jeremy in Chicago. His dad was a mentor to me. And he used to hire me as a carpenter, though I realized that it was just a way for him to give me money.”

Knowing Macy’s history with the Pivens makes the final task of the day feel a little mean-spirited, but still I hand him a box of sushi—tuna no less—from Blue Fin. Would he like some? Macy laughs. “You bought it today? Are you kidding? I’m going to have it for dinner.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.