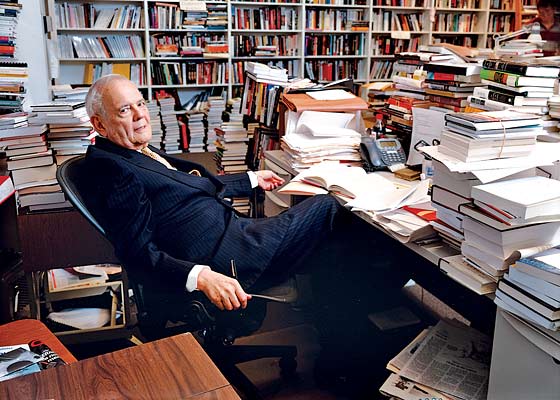

It’s late on a Friday afternoon in summer, and the city has the deserted feel that it gets just before a weekend. The streets are empty; taxis have their for hire lights on at the witching hour, the time when they’d normally be headed for the garage. But on the fifth floor of 1755 Broadway, a nondescript office building on the corner of West 56th Street, work—serious work—is in progress. The “Fall Books” issue of The New York Review of Books is being put to bed. “I’ll be here all weekend,” says Robert Silvers cheerfully.

On my way up in the elevator, I had wondered if Silvers would be wearing a tie: I’ve never seen him without one. The tie is there but askew, the top button of his white shirt undone. Instead of his usual dark suit, he’s got on a red cardigan. For anyone else, this would be like showing up at the office on casual Friday in a T-shirt and ripped blue jeans.

It’s been a difficult time. In June, Barbara Epstein, Silvers’s co-editor at the Review for 43 years, died of lung cancer at the age of 77. He has been commuting from Lausanne, Switzerland, where his longtime companion, Grace, Countess of Dudley, is recovering from a serious car accident.

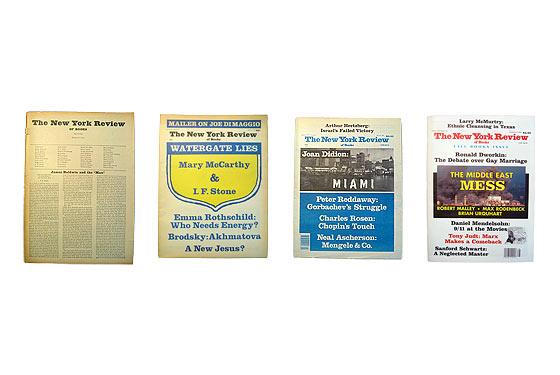

Between us on a table in the windowless conference room is a recent issue: volume LIII, number 13. The cover lists a sampling of its contents: the venerable Harvard professor Stanley Hoffman on three books about American foreign policy; Russell Baker on Roger Angell’s memoir, Let Me Finish; and a dispatch from Bolivia by the Latin American journalist Alma Guillermoprieto. It’s an eclectic but impressive mix—one that has made The New York Review of Books the premier journal of the American intellectual elite virtually since its inception during the New York newspaper strike of 1963.

Also in this issue are eleven brief tributes to Epstein by such old friends as Larry McMurtry and Gore Vidal. I myself knew her only from literary cocktail parties, but Luc Sante’s portrait brings her back: “She was funny, mischievous, infectiously enthusiastic, occasionally prodigal, sometimes incorrigibly teenaged, the best sort of company. The world is a much lonelier place without her.”

So is the masthead, which now contains, after editor, the single name Robert B. Silvers. Magazines are not, by nature, co-edited: Their identities depend upon the imposition of a single voice and sensibility. Paris Review was the expression of George Plimpton; Granta was the expression of Bill Buford. But The New York Review of Books was the co-expression of Silvers and Epstein, two strikingly original people who managed to speak with one editorial voice. The question being asked these days by the magazine’s loyal readers and contributors is, can it survive under the editorship of a 76-year-old literary widower who, however robust, hardworking, and determined, will now have to grapple with the burden of going it alone?

There are larger questions, too. Can The New York Review of Books survive without its founders’ specific genius. political and literary journalism it practices? A typical Review piece runs to 4,000 or 5,000 words, is pitched to readers who often have several advanced degrees, and may contain footnotes. Its intellectual and physical heft—the “Fall Books” issue came in at 100 pages—requires the kind of attention that becomes harder and harder to sustain with every new technological gadget we hitch to our belts or curl around our ears. The audience that grew up reading the Review is now in its fifties or older. Will the Review find a new audience with a younger demographic, or will it wither away like the state in Friedrich Engels’s prophecy, to be supplanted by new vessels of intellectual content? For its overwhelmingly liberal, hypereducated urban readership, it’s hard to imagine a Reviewless world.

The genesis of the Review is a literary legend by now. One night during the early weeks of the strike, Jason Epstein, then an editor at Random House, and his wife, Barbara (they were divorced in 1980), were having dinner with Robert Lowell and his wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, the Epsteins’ neighbors on West 67th Street.

Their block, between Central Park West and Columbus, is on a leafy street lined with elegant old apartment buildings known for their wood-paneled walls and double-height living rooms—“the last gasp of true / Nineteenth Century Capitalistic Gothic,” as Lowell once described it. But the artists for whom these grand ateliers were originally built had long since departed for more affordable neighborhoods, replaced by editors and writers who held down actual jobs.

Jason Epstein had already made his name in the literary world by figuring out, as a 25-year-old editor at Doubleday, that a market existed for quality paperbacks. Thus was born Anchor Books, which offered to a newly literate middle and upper-middle class cheap yet elegant editions of the classics, along with new titles destined to become classics—the “backlist,” as such books are called in the business. By now, of course, it would be hard to imagine publishing without Epstein’s discovery: If you removed every trade paperback from the shelves of Barnes & Noble, there would be nothing left but the “frontlist” hardcover titles allotted their six-week window before being returned to their publishers or pulped.

Among the books on the first Anchor list was To the Finland Station, by Edmund Wilson, the dean of American letters. Wilson’s narrative account of the intellectual background to the Russian Revolution, which he traced back to the works of Marx, Engels, and their philosophical precursors Hegel, Taine, and Michelet, was an ideal prototype for Epstein’s concept: Written in workmanlike prose, it combined the virtues of journalism and scholarship. It was informative and easy to read—upper middlebrow.

In the early days of the Epsteins’ marriage, Barbara was “the wife,” a familiar type in that pre-feminist era, when in even the most progressive intellectual circles smart and sexy women deferred to their husbands. Born in Boston of Russian- and German-immigrant parents, she entered Radcliffe at the age of 16 and fell in with the arts-and-letters crowd. “The day we met she was sitting in the Radcliffe College cafeteria, smoking,” wrote the novelist Alison Lurie in one of the memorial tributes published over the summer in the Review. “Her black turtleneck Jersey, unstructured hair, and stack of books not on any assigned list instantly marked her as what would presently be called a beatnik.” She was known around campus as “Bubsey.”

The poet John Ashbery was also a classmate and friend. They met their freshman year, in the fall of 1945, on the steps of Widener Library. “I was struck by her clothes,” Ashbery recalls. “She had a ragbag, pre–Annie Hall look, odd bits of costume.” They “took tea” at the Window Shop on Brattle Street and attended chic Brit films like Black Narcissus and Whisky Galore.

Epstein’s first post-college job was at Doubleday, where she discovered and edited Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl. A stint at Partisan Review—a useful training ground with its stable of high-strung, at times bellicose contributors—prepared her for the next and last chapter of her long working life in literature.

“There is a whole sort of Cultural Establishment,” Wilson noted in the journal he kept, chronicling the literary life. The Epsteins and Lowells were “the headquarters of the literary department.” Still only in their thirties, they were a celebrated pair, Scott and Zelda minus the alcohol-fueled marital theatrics—a power couple, to invoke the groveling term of our own status-obsessed day. They even made it onto the guest list for Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball at the Plaza, destined to become a mythic social event. Held in honor of the Washington Post’s publisher, Katharine Graham, the ball was attended by 500 of the host’s glamorous friends, from Frank Sinatra and Mia Farrow to Lionel and Diana Trilling—in a literal sense, the smart crowd.

Their parties were famous. On any given night, you might find in the Epsteins’ high-ceilinged living room a cross-cultural crowd of iconic sixties figures: Lillian Hellman, Jane Jacobs, Abbie Hoffman, Philip Roth. “One was always aware that there was a large and complicated world out there,” recalls the Epsteins’ daughter, Helen, now a science writer at work on a book about aids in Africa. (The Epsteins’ other child, Jacob, is a TV writer in Hollywood.) “The whole place would be flung into turmoil—servants running around everywhere, a hundred people gathered in the living room. Then there would be Dad’s oddball interests, some guy who had invented the first mail-order catalogue, this person who had made a high-end cooking pot, or the great mathematician Norbert Wiener.” It was before the age of militant moderation that has seized the aging boomer intelligentsia of Manhattan—before the Death of Fun. “These evenings at the Epsteins’ are so strenuous that I am usually a wreck the next day,” Wilson complained.

Depicted in Wilson’s journals as a precocious curmudgeon, prone to grousing but “energetic and full of ideas,” Jason Epstein was a brilliant literary entrepreneur. (Or is that an oxymoron?) He would go on to found the Library of America, the Gardening Book Club, and the Readers’ Catalogue, a telephone-book-size compendium of books in print that would have had a good chance of success if it hadn’t been blown out of the water by Amazon.

“We were both working at Doubleday, but we met in the Village,” Epstein says, recalling the pre-Review days. “Barbara was wearing a black leotard and had her hair cropped short. I fell in love with her and never got over it.”

We’re in the spacious kitchen of his apartment in the old Police Building down on Centre Street, which was renovated into co-ops some years ago. With its marble pillars and chandeliers, the lobby has the gloomy splendor of a government reception hall in Naples. Above us hang rows of copper pots and pans—we could be on the set of a Martha Stewart show. (Among his other achievements, Epstein is a fabled gourmand.)

Remembering the historic dinner with the Lowells, he says, “We were sitting around and talking about the newspaper strike, and I said something like, ‘It’s wonderfully quiet these days. We don’t have to read The New York Times Book Review.’ ” Epstein is generally credited with the epiphany that launched a thousand issues of The New York Review of Books: Why not start a magazine themselves? “We were sort of jokingly saying it would be fun,” Elizabeth Hardwick recalls. “We thought of it as a one-shot.” The next morning, Epstein called Bob Silvers and asked him to become its editor.

At the time, Silvers was an associate editor of Harper’s. “I never thought Bob would leave the magazine,” Epstein says. “He had what seemed like a very good job.” But Silvers had been thinking along the same lines. “There was a need for a book review, but it was thought to be hopeless,” he says, employing his signature indirect syntax. “In the absence of the Book Review, there were no reviews, no place for ads. Publishers were going crazy. The thought emerged that perhaps we could start our own.”

Silvers was a good choice. A member of the raffish expatriate crowd who collected around The Paris Review in the fifties, he became Paris editor of the newly formed journal when its founder, George Plimpton, decamped for New York. His roommate (or boatmate, as it happened) was the future bandleader Peter Duchin, who had acquired a Thames River barge and moored it on the right bank of the Seine, hard by the Crazy Horse Saloon. “Bob was a workaholic,” recalls Duchin. “He’d be off in the corner editing a piece while I was having a jam session.” Silvers shows up with some regularity in Duchin’s memoir, Ghost of a Chance, which offers a vivid glimpse of their floating salon. Duchin played Fauré on his upright piano while Silvers annotated galleys: “There was always something delicious to eat on the stove—a pot-au-feu, coq au vin, boeuf bourguignonne … ” They didn’t have a phone; writers were forced to board ship in order to conduct a meeting.

In 1959, Silvers returned to New York and the Harper’s job. Not yet 30, he had already gained a reputation as the possessor of a formidable intellect. The son of a poultry farmer who’d left Wall Street for the pastoral life in Farmingdale, on Long Island, he graduated from the University of Chicago at the age of 17, one of those geniusy adolescents—Susan Sontag was another—who arrived at the university, Schopenhauer in hand, while their high-school classmates back home were reading Silas Marner.

A common refrain you hear whenever his name comes up is, Bob knows about everything. “He could go from the obscurantist dialectics of some long-forgotten seventies-era Marxist groupuscule to the niceties of modern Austrian politics,” observes Tony Judt, a frequent contributor to the Review. Nor was his copious store of knowledge confined to matters of literature and politics. He was also familiar with the latest theories of child-rearing—though he has no children of his own. “When I had a baby, he knew everything about that,” says Alexandra Schlesinger (wife of Arthur Jr.), who was his first assistant. “He knew what to feed the baby, he knew all about neonatal care.”

Newly installed in his job at Harper’s, Silvers commissioned Hardwick to write an article for the magazine on the state of our literary culture. The result, “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” provoked a tumult. (Even the then-owner of Harper’s, Cass Canfield, wrote a letter of protest.)

Hardwick’s main argument was not just that reviewers were too quick to praise; they were dull. “Sweet, bland commendations fall everywhere upon the scene; a universal, if somewhat lobotomized, accommodation reigns. A book is born into a puddle of treacle; the brine of hostile criticism is only a memory.” No critic or journal compelled one’s attention. The Saturday Review of Literature had a peak circulation of 630,000, but in order to maintain it, it had dropped “of Literature” from its name. The Times Book Review, then as now the most influential journal in America devoted primarily to reviewing books, was unexciting. Where in America could you find critics of the stature of such English literary titans as Cyril Connolly and V. S. Pritchett? “The adaptable reviewer, the placid, superficial commentator might reasonably survive in local newspapers,” Hardwick concluded, “but for the great metropolitan publications, the unusual, the difficult, the lengthy, the intransigent, and above all, the interesting, should expect to find their audience.” Without knowing it, Hardwick had written a manifesto for The New York Review of Books.

“Here we are in the hectic whirl of putting out the new book review,” Lowell wrote the poet Elizabeth Bishop that March. “Lizzie [Hardwick] is furiously engaged and in a way making inspired use of her abilities—for God knows we need a review that at least believes in standards and can intuit excellence.”

The morning after their fateful dinner, Lowell went to the Midland Bank and borrowed $4,000 against his trust fund. Epstein and Silvers made the rounds of the publishing houses, raising money for “the paper”—as Silvers likes to call it—by selling ads. At night, they worked in the Harper’s offices. “We rang up some of the writers we admired most and asked them to contribute something within three weeks,” recalls Silvers. “There was no question of payment.” The issue was laid out on the Epsteins’ dining-room table, with Barbara as co-editor.

The table of contents was imposing. Dated February 1, 1963, the inaugural New York Review of Books contained work by William Styron, Dwight Macdonald, Norman Mailer, and Mary McCarthy, among numerous distinguished others. “Mary wrote this review of Naked Lunch that was thrilling,” Silvers recalls. (How many would apply that word to a book review?) The issue also contained the first—and last—editorial ever to appear in its pages. The Review would abjure writing about books “trivial in their intentions or venal in their effects, except occasionally to reduce a temporarily inflated reputation or to call attention to a fraud.” The print run was 100,000 and sold out instantly. Within a matter of weeks, the editors had gotten more than a thousand letters. “That was the real step,” Epstein says, “to imagine an audience that size.”

Raising money came easily after that. Brooke Astor and Sallie Bingham, a scion of the Kentucky newspaper dynasty, were among the high-toned benefactors who provided funds. Within four years, the Review was in the black, where it has remained for the past four decades.

Silvers and Epstein were a harmonious team—she called them “Ma and Pa.” As in all marriages, there were occasional clashes behind closed doors, but “we knew each other so well that we could have a kind of shorthand,” says Silvers. “We passed things back and forth in the most natural way.” Wilson recorded in his journal, “Now Barbara, who before was so quiet and kept herself in the background, with The New York Review of Books, has become quite a brilliant figure.”

Around the office, Barbara was the lighthearted one, business-like with an editing pencil but sociable and fun. She sent bottles of champagne to her authors, wrote notes, even loaned them money. She also encouraged her assistants to write for “the paper.” Luc Sante, who has been contributing to the Review for a quarter of a century, started out, William Morris–like, in the mailroom. A year later, Epstein hired him as her assistant. “I was flabbergasted. I couldn’t type, couldn’t make a restaurant reservation on the phone.” So how did he get the job? “She saw that I had a literary bent. I brought books into the office and left them lying around.”

Refuting the often-expressed complaint that the Review is a closed shop, Epstein liked to bring young writers into the fold. Daniel Mendelsohn, an accomplished classicist and all-purpose scholar, was tapped out of the blue. “They just sent me a book and asked if it would interest me,” he says. “It was like receiving the angel Gabriel.” She was “motherly,” attests the novelist Cathleen Schine. “She would call up and say, ‘Wouldn’t it be fun if you did this for us?’ You didn’t feel cowed or burdened.”

Mark Danner was a depressed, unemployed recent grad living above the Hong Kong restaurant in Harvard Square when he decided, on impulse, to call the offices of the Review at 8:30 on a Friday night. “I was certain no one would answer, but Barbara picked up the phone.” She invited him to come down on Monday morning. “I was wearing a powder-blue sports coat, a red tie, red-and-white candy-striped shirt, and white pants. My only grown-up clothes. Looking back on it, I’m surprised they let me in the door.”

Despite Danner’s sartorial extravagances, the interview went well. “I mentioned Auden, and she launched into a ribald story about ‘Wystan.’ She was beautiful and charming and mildly naughty. I was completely smitten.”

Still to come was an inquisition from Silvers. “Then Bob came in, coiffed and tanned, in a beautiful suit like someone out of a movie. He flipped through a long essay I’d written on El Salvador, seeming to read it instantaneously.” After a spirited debate about the nature of the left in Central America—“He knew the subject inside out”—Silvers abruptly left the room. “He left me sitting there in the middle of the discussion. I thought there was no way I’d gotten the job.” A few hours later, Barbara called and offered Danner a job.

Being an assistant to Bob or Barbara was more than just a job, though; it was the first stage of a vocation. Others include the novelist Susan Minot; the biographer Jean Strouse; S.J. Perelman’s companion, Prudence Crowther; and the editor Shelley Wanger. “Everyone was absurdly overqualified,” says Wanger.

The office was chaos. “You walked in and it looked like a fan had spread papers over everything,” recalls Minot. It was that glorious and long-ago time when people smoked cigarettes; Luc Sante rolled his own. Silvers had a brass stand-alone ashtray filled with butts. The furniture was secondhand—not shabby-chic but shabby. (For some reason, Silvers’s desk was adorned with the presidential seal.) But where else could you meet Susan Sontag, Czeslaw Milosz, and Joan Didion? Oliver Sacks would pop in for a chat; A. Whitney Ellsworth, the magazine’s Wasp publisher, arrived with his hunting dogs.

The work ethic was deeply ingrained. Silvers sometimes spent the night at the office. In the late afternoon, he’d rush out to a lecture at the Council on Foreign Relations, show up at a dinner party, and then head back to the office to deal with the next breaking crisis. One night, just before the outbreak of the Iraq war, he phoned Tony Judt and begged him to revise a full-page ad that was about to run in the Times protesting the war. Judt was in London, nursing a head cold, when Silvers called. “Woozy with decongestants but given an adrenaline surge by the urgency of the matter and Bob’s distinctive powers of persuasion, I sat down, hammered something out, and fired it back by fax in the middle of the night”—New York time.

Silvers had not one but four assistants. Nathaniel Rich, now an editor at The Paris Review (and the son of the Times’s Frank Rich), started out as an intern at the Review. He sat at one of the four desks clustered in front of Silvers’s desk, “like one of the law clerks in a Dickens novel.” The clerks had erected a wall of galleys to protect themselves; Silvers would start dictating a letter to whoever peered over the trench. “I was right in the line of fire.” Rich was a Yale graduate, but the look was hardly Ivy League. One of the assistants had a shaved head and tattoos: Rich describes him as “a mix between New York intellectual and San Diego surfer boy.” People around the office thought he was a messenger.

Silvers’s zeal as an editor is legendary. Every contributor has stories about messengers arriving with a packet of galleys at their door on Christmas Eve or getting a call from Silvers at their remote farmhouse in Provence as they were sitting down to Sunday dinner. Daniel Mendelsohn recalls the time Silvers called him with a single proposed revision: “We did think that the word compelling could be avoided.”

The goal is always to make pieces—one of Silvers’s favorite words—“stronger.” He edits by pencil and often goes through five or six galleys. He shows me a tribute by Sam Tanenhaus, current editor of the Times Book Review, in Le Monde. Tanenhaus describes Silvers as impitoyable—pitiless. Silvers jabs his finger at the word and repeats with delighted emphasis, “Impitoyable.”

From the beginning, the Review leaned to the left and wasn’t shy about it. (One of its most controversial articles was a piece on the growing racial unrest in American cities illustrated with a diagram on the cover showing how to make a Molotov cocktail.) The magazine’s birth coincided with the birth of the civil-rights movement and the war in Vietnam, an event it closely monitored. Ellen Willis, Tom Hayden, Andrew Kopkind, and other veterans of the New Left (Greenwich Village branch) were regular contributors. Mary McCarthy sent dispatches from Hanoi; the crusty muckraker I. F. Stone hammered away at the Johnson administration’s disinformation campaign in Cambodia. Throughout the sixties and early seventies, amid its erudite coverage of books about medieval art, Latin poetry, and the history of literary criticism, the Review trained a keen eye on the events that would define that turbulent era: the trial of Bobby Seale, the Columbia riots, the march on the Pentagon.

Progressive in its politics, it was anything but doctrinaire. Paul Goodman’s “Reflections on Racism, Spite, Guilt, and Violence” was a skeptical look at the notion that blacks were the victims of white middle-class racism; Hannah Arendt’s essay “Reflections on Violence” asserted that the New Left was ignoring Marx: “The old society” would be brought down not by violent revolution but by the contradictions of capitalism. Then there was Christopher Lasch’s series of pieces on the tendency of the left to distract itself with cultural issues—the genesis of his classic The Agony of the American Left. If the Review was radical, its radicalism was nuanced.

Philip Nobile claimed in his envious book-length tirade, Intellectual Skywriting: Literary Politics and The New York Review of Books, that by the early seventies, the Review had receded into “a literary magazine on the British nineteenth-century model, which would mix politics and literature in a tough but gentlemanly fashion.” Nobile exaggerates. There was plenty of acerbic political commentary in the years that followed. The Review continued to rail against the Reagan era’s push for tax cuts and the consolidation of military power. But it was also refining the tone of high-minded, clubbable Oxbridge urbanity that has prompted the magazine’s detractors to refer to it as “The New York Review of Each Other’s Books.” Thumbs up for David Lodge on Frank Kermode, Frank Kermode on John Bayley, and John Bayley on David Lodge.

It was 9/11 that revived the Review’s fighting instincts.

Two years ago, a lengthy piece in The Nation heralded “The Rebirth of The NYRB.” Written by a young journalist named Scott Sherman, it argued that the Review had once again become “a powerful and combative actor on the political scene.” Week after week, it carried dispatches from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Guantánamo Bay. Mark Danner and Orville Schell reported from Iraq. That courageous warhorse Norman Mailer, still contributing to the Review 40 years after his appearance in the first issue, wrote a piece denouncing the United States under Bush as “a monumental banana republic.”

But what is the Review’s place in that republic? Is it read beyond the confines of New York—by which I mean Manhattan and its cosmopolitan outposts Berkeley, Cambridge, and the university-dominated villages of Ann Arbor and Madison, New Haven, and Hyde Park? How much influence does it have in the Real World? Silvers points to the article by Mark Danner on the “dodgy dossier” that justified Tony Blair in joining the invasion of Iraq. “We were the only publication to run the full text of the Downing Street memo!” he says. Elizabeth Drew’s piece on the Bush administration’s pursuit of unchecked executive power “had an amazing effect. People in Congress read it.” Whether this constitutes influence is hard to say. “I have no great confidence that anything is influential,” says Silvers. “If it is, great.” But he values influence far less than independence—both ideological and financial.

It is a sad fact of life in America that the general audience for so-called intellectual publications, both left and right, is so small that most of them require subsidies in order to survive. Rupert Murdoch owns the neocon Weekly Standard; a consortium of prominent liberals, including Paul Newman, owns The Nation; and a consortium of no fixed ideology that includes Harvard associate professor Martin Peretz and Roger Hertog, a major donor to the conservative Manhattan Institute, owns The New Republic. The Review, too, now has a wealthy owner, Rea Hederman, whose family owned the Jackson, Mississippi, Clarion-Ledger.

“We knew each other so well that we could have a kind of shorthand,” says Silvers of Epstein. “We passed things back and forth in the most natural way.”

Hederman was muscled out of the editorship after he transformed the Clarion-Ledger from an openly racist newspaper into a Pulitzer Prize–winning voice of the civil-rights movement. He moved to New York, made a fortune in the cable-TV business, and bought the Review in 1984 for about $5 million. But he’s not a benefactor: Its circulation of 127,000, the modest fees it pays contributors, and its attractiveness to publishers as a venue for book ads have made the paper modestly profitable. “We’ve never had any hesitation about taking any position that we thought was right,” says Silvers. “There is no foundation, government, or other force in the world that can tell us what to do.”

The death of the “public intellectual” has been announced more often than the death of the novel. In Public Intellectuals: A Study of Decline, University of Chicago law professor Richard Posner spends more than 400 pages anatomizing the disappearance of this type. His book, with its “quantitative analysis of public intellectual activity,” attempts to calculate the relative importance of 727 intellectuals—not 726 or 728—according to such criteria as “media mentions,” “scholarly citations,” and helpful demographics: “Jewish/non-Jewish,” “Right-Leaning/Left-Leaning,” “Black/Nonblack” (a reversal of racial categories meant to show how tolerant the author is). To assess the role of public intellectuals, you have to assess the role of “policy intellectuals”—the neoconservatives who haunt the corridors and cafeterias of the American Enterprise Institute, the Cato Institute, and the Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C. One tends to forget, in the cloistered atmosphere of literary New York, that there’s another kind of intellectual who resides in a different city—in not just ideological but geographical proximity to power. The Weekly Standard, edited by William Kristol, messengers 30 copies to Dick Cheney’s office every Sunday morning

In the literary world, too, the Review faces competition. Though they can’t begin to challenge the Review’s intellectual hegemony, the journals of Generation X—Open City and The Believer and n+1—now have followings of their own. Keith Gessen and Benjamin Kunkel, two of the editors of n+1, also write for The New York Review of Books, but their real energy goes into the journal they founded two years ago. n+1 looks like the old Partisan Review and sounds like it, too, with its mix of somber symposia on “American Writing Today” and political essays. (“Gut-Level Legislation, Or, Redistribution,” by Mark Greif, makes the case for capping incomes at $100,000. Good luck, Mark.)

Dave Eggers, meanwhile, has created a virtual literary franchise. In addition to publishing a line of books, he presides over two literary journals: McSweeney’s, which features short stories, and The Believer, a monthly with an edgy design—large trim size, odd illustrations—and idiosyncratic features. My own favorite is Nick Hornby’s column, “Stuff I’ve Been Reading,” which is mostly about stuff he hasn’t read. Interestingly, the “Books Bought” list is almost always at variance with the “Books Read” list.

Can the Review hold its own in this newly transfigured literary landscape? The talent is there. As the old generation—Theodore Draper, Isaiah Berlin, Noel Annan—dies off, a new generation of critical thinkers has emerged to take its place. Mark Danner, Tim Judah, and Timothy Garton Ash, three of the Review’s veteran political commentators, are only in their forties or early fifties, as are Tim Parks and Daniel Mendelsohn, two of its most able critics.

And the Review is more than a magazine, more than a collection of talented writers and editors; it’s a world of its own. The combative letters column; the bookish personals; the pages and pages of publishers’ ads; even the real-estate listings for country homes and flats, which define the geography of the Review’s sophisticated readership (Paris, London, Tuscany, New York, San Francisco, Boston): Combine these elements and you have a distinctive identity composed of idiosyncratic customs, habits, styles—in other words, a culture.

What will become of its inhabitants? For now, Bob Silvers is managing to put out the paper on his own. At 76, he shows no sign of slowing down—or of delegating responsibility to anyone else. No likely successor waits in the wings. For a time, the name of Louis Menand, author of The Metaphysical Club, which won a Pulitzer Prize, mysteriously appeared on the masthead as “contributing editor.” But Menand is a full professor at Harvard now and unlikely to return to the fold. Another rumored candidate is Ian Buruma, who has been writing for the paper since 1985. Buruma grew up in the Netherlands, teaches at Bard, and has written acclaimed books on subjects as diverse as Japanese culture and Muslims in Europe: He possesses the cultural and intellectual range for the job. But he won’t even be drawn into a discussion of the issue. “I hope Bob will go on for a hundred years,” Buruma says. “He’s doing it very capably, and he has an immense appetite and capacity for hard work.”

Silvers also deflected the question. “I’m terrifically involved in the next issue,” he said, a note of urgency in his voice, when I asked him if he’s thought about a successor. “You have to think of book after book. You’re asking people to spend weeks of their lives writing a review. It’s an important commitment, a huge responsibility.” In other words, no.

Phones are going on night,” a woman’s voice intones over a speakerphone on the conference table where Silvers and I have been talking on this late-summer afternoon. I get up to leave, but somehow the subject of Melville has come up and he wants to show me a book. “Andrew Delbanco’s?” I ask, mentioning the recent highly praised biography. We agree that the Delbanco book is very fine indeed, but Silvers has another book in mind.

We adjourn to a vast corner room filled with ziggurats of books, among which he instantly locates Exiled Royalties: Melville and the Life We Imagine, by Robert Milder, a professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis. A cleaning lady in a blue uniform tries to sweep around him, but Silvers is oblivious, intently focused on the subject at hand. Milder’s book, he says, searching for a word, is “exigent”—it has to be consulted, has to be read. Nothing matters more.

He shows me out. Propped on the counter next to a pile of issues is a photograph of Barbara Epstein.