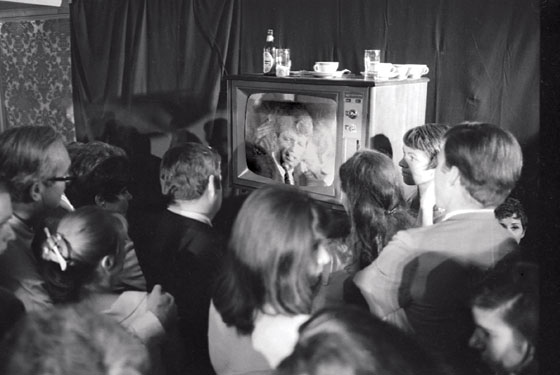

Pierre Salinger watching Robert Kennedy declare victory in the California primary on TV.

Photographs from RFK: A Photographer’s Journal by Harry Benson, published by powerHouse Books. Copyright © 2008 by Harry Benson.

Around 8:30 p.m., we were in Suite 516 of the Ambassador Hotel, whose windows looked down upon Wilshire Boulevard. In memory, there were about 30 men and women in the long windowed suite, talking in knots, most leaning forward, mouths to ears, like conspirators. They were wealthy California Democrats, big-time lawyers, movie executives (but no stars), political professionals, journalists, including my friends Jack Newfield, Budd Schulberg, Jimmy Breslin, and my younger brother Brian. It was June 4, 1968. There were no laptops, or cell phones, or BlackBerrys, or cable-television news either. So telephones rang insistently in the suite, were picked up, and names were called in stage whispers. Or the door would open, someone in shirtsleeves would arrive, whisper the latest news, then turn abruptly and leave. A few people mixed drinks at the bar, clunking ice, nibbling from plates of rolled-up room-service ham and wedges of Cheddar and Swiss cheese. There was no music. This was not, after all, a party. That would be later, after the results were in, at a place called The Factory. This was politics. This was, in fact, the last stop for the campaign of Robert F. Kennedy in California. Downstairs, the ballroom was full, waiting noisily for news of a victory and a chance to roar for their candidate.

While we waited in 516 for the polls to close and the returns to come in, I talked for a while with the movie director John Frankenheimer. The advertising agency Papert, Koenig, Lois, Inc., had hired him in March to work with the Kennedy campaign on shooting promotional material, including some commercials. He and Kennedy had become friends, and the candidate had spent the night before in Frankenheimer’s home in Malibu. On this Tuesday, Frankenheimer had driven Kennedy to the Ambassador, where they arrived around 7:30 p.m. Like me, Frankenheimer was a native New Yorker, and I noticed that he referred to Kennedy as Bob, as I did. Where we came from, people named “Bobby” were either 9 years old or professional ballplayers. We talked a bit about the town that spawned us, and then about Frankenheimer’s great paranoid masterwork from 1962, The Manchurian Candidate, which starred Frank Sinatra and Laurence Harvey. It had been withdrawn from public viewing after the killing of Jack Kennedy in 1963 (it would finally be rereleased in 1988). The story, based on a novel by Richard Condon, was about programming a man to assassinate a presidential candidate.

“Do you think it could happen in what is laughingly called ‘real life’?” I asked him.

Frankenheimer smiled in a nervous way, and glanced at the door of the suite.

“Yeah.”

Across the hall, in Room 511, Robert Kennedy was waiting, too. This was the night of the California primary. A week before, Kennedy had lost the Oregon primary to McCarthy, his first loss in the near-frantic campaign that had started on March 16. If he lost tonight, if California went to McCarthy, it would be impossible to get the nomination at the convention in Chicago in August. His wife, Ethel; a few of his children; close family friends; some of the top professionals in the campaign: All went in and out of 511, some to deliver bulletins, others to provide laughter or diversion. Even Freckles, the homely springer spaniel who had become a star at Kennedy’s side during the campaign, had made it into 511. There, Kennedy sat in shirtsleeves, the cuffs turned up, his tie loose, grinning with a kind of dark Irish fatalism in his eyes.

I didn’t meet Kennedy until Saint Patrick’s Day, 1966. I had been covering the war in Vietnam for the New York Post, and Kennedy had sent me a letter admiring my columns and inviting me to call him. We agreed to meet at a Saint Patrick’s Day breakfast at Charley O’s, a restaurant near Rockefeller Center. The place was full of the usual green ties and green cardboard derbies and people getting ready to march. I saw Kennedy across the room, talking to various people. He was better-looking than he was in most photographs, the hair fashionably long, sometimes falling across his brow to be brushed back with a quick flick. He seemed taller than he actually was (five-foot-nine) and moved athletically, like a good middleweight. He was quick to smile a rueful smile, usually in a self-deprecating manner. But in his eyes, as I came closer to introduce myself, I could see an almost permanent sadness. By all accounts, he’d been wrecked by his brother’s death.

“How are ya?” he said.

I said I was fine, for this hour of the morning, and we began the friendship. In the few years that followed, I would see him fairly often, in situations that were off the record. He liked me, Breslin, and Newfield because we all came originally from the New York beyond Manhattan: Breslin from Queens, Newfield from Bedford-Stuyvesant, I from blue-collar South Brooklyn. He was curious about the people that shaped us, and the places we’d lived in—so different from the world that shaped him. He would often call us, one at a time, when he was in town, and take guided tours into those worlds. He didn’t want to see it from the back of a passing car. He’d want to pull over, approach a group on a summer stoop, or entering a church, or an Irish bar. He learned a lot from the people he met on those small journeys. And the people he met learned a lot from him.

At the same time, things were darkening in the United States. James Meredith was shot by a sniper while engaged in a lonesome march down a road in Mississippi. He lived. And I joined dozens of reporters following Martin Luther King Jr. on the intended route of Meredith’s march to Jackson, Mississippi. The following month, I was in Chicago, where a man named Richard Speck had murdered eight nurses. The next month, I was in Texas to report on a former altar boy named Charles Whitman who had carried a trunk full of rifles and ammo to the top of a tower at the university in Austin and shot sixteen people dead and wounded more than 30 others before he was killed by the police. In New York, I covered the first deaths of several people who had tried to fly like Superman from the rooftops on New York’s Lower East Side while blitzed on acid. Now heroin seemed to be everywhere in New York, and the crime rates began to soar. In October, I was off again to Asia. We were told off the record that William Westmoreland wanted troop strength to surge to 700,000. I had begun to feel on that trip that this part of the story was being written by the Evelyn Waugh who gave us Scoop.

In between, every month or so, I would speak to Kennedy on the telephone, or visit him in his apartment near the United Nations. We talked about the world and human folly and almost everything else, except Jack. Bob had that Irish gift for making laughter out of a dreadful world. Then in the fall of 1967, I moved my column to Newsday, where Bill Moyers was the publisher. I also moved my family and my books to Washington. Or more precisely, to a rented house in McLean, Virginia, not far from the Kennedys. Now we saw them both, along with the kids, and Brumus the big dog, and Freckles the smaller one. I started to look at Washington in a more sustained way. What I saw repelled me. On all sides, positions were hardening. Those who supported the war sneered at those who opposed it. Each side demonized the other. Some of the antiwar demonstrators were repulsive: self-righteous, snarling, judgmental in the worst way. The supporters of the war were repulsive in a different way, prepared to fight to the last young man. At the same time, the usual Washington hustlers kept hustling, working the lobbies of power, corrupting politicians, preventing all political movement that was not intended to put money into bank accounts. On day after day, it felt as if the country was coming apart.

Kennedy sensed this too, but was frozen. He should have been shaping a run against Lyndon Johnson. But all the political Kennedys were a combination of reform and regular Democrats. Their mother, after all, was the daughter of Honey Fitz from Boston. And it would have been a violation of all the rules to turn publicly against your own party. Kennedy also knew (as Newfield once pointed out) that Vietnam was “liberalism’s war.” Put together by liberals. Defended by liberals. Sold by liberals. Including Jack Kennedy.

A few times I ranted about where the Goddamn War was taking us.

“I know, I know,” he said, with anguish on his face, and I knew it was time to change the subject.

In the last weeks of 1967, I gave up the column and resigned from Newsday. I hated what I’d been writing, for its bitterness and darkness. I was a natural optimist, a son of Irish immigrants who had come through the Depression and the War without giving up their belief that things would soon be better. If not tomorrow, then the day after tomorrow.

I had written part of a novel set in Rome, and decided that we would go to Ireland for as long as it would take to finish it. I went to tell Bob Kennedy. He kept shaking his head, saying little, holding his chin with his bony hands. “Goddamn it,” he said. “Goddamn it all to hell.”

We found a nice small house in Howth just north of Dublin, with hills behind us, and the sea a short walk from the front door. I was relieved to be away from the States and threw myself into the novel. This worked for about a week. The war would not go away. It was on the front pages of the Paris Herald Tribune and the serious British and Irish papers. It was on the Irish radio too, and the BBC. Eugene McCarthy was making his own run for the presidency now but was given no chance by the experts. In late January, Kennedy said again, very clearly, that he would not run against Lyndon Johnson.

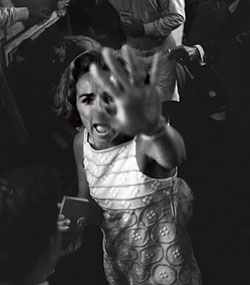

Kennedy’s wife, Ethel, screaming, “Give him air, give him air.”Photo: Harry Benson

Then, at the end of January, news came about the Tet Offensive. The Communists—North Vietnamese and Vietcong from the south—had risen everywhere in South Vietnam, including Saigon. The great Eddie Adams photograph of General Nguyen Ngoc Loan shooting a Vietcong suspect in the head on a Saigon street would appear everywhere in the world, including Ireland. My brother John, age 18, was in the Army now, somewhere near Pleiku. I listened to the BBC late into the night and in the morning sat down and wrote a letter to Kennedy.

It said:

Dear Bob:

I had wanted to write you a long letter explaining my reasons for why I thought you should make a run for the Presidency this year. But that’s too late. I read in the Irish Times this a.m. that you had made a hard announcement, and that small hope is gone, along with others that have vanished in the last four years.

I suspect that all nations have their historical moment, some moment when it all seems to have been put together as an idea: our moment was 1960–63. I don’t think it’s nostalgia working or romanticism. I think most Americans feel that way now.

The moment is gone now, and we have grown accustomed to living in a country where nobody would protest very much if Jack Valenti replaced John Gardner.

I wanted to say that the fight you might make would be the fight of honor … I wanted to say that you should run because if you won, the country might be saved … If we have LBJ for another four years, there won’t be much of a country left. I’ve heard the arguments about the practical politics which are involved. You will destroy the Democratic Party, you will destroy yourself. I say that if you don’t run, you might destroy the Democratic Party; it will end up nationally, the way it has in New York, a party filled with decrepit old bastards like Abe Beame, and young hustlers, with blue hair, trying to get their hands on highway contracts, It will be a party that says to millions and millions of people that they don’t count, that the decision of 2,000 hack pols does. They will say that idealism is a cynical joke; that hard-headed pragmatism is the rule, even if the pragmatists rule in the style of Bonnie and Clyde.

I wanted to remind you that in Watts I didn’t see pictures of Malcolm X or Ron Karenga on the walls. I saw pictures of JFK. That is your capital in the most cynical sense; it is your obligation in another, the obligation of staying true to whatever it was that put those pictures on those walls. I don’t think we can afford five summers of blood. I do know this: if a 15-year-old kid is given a choice between Rap Brown and RFK, he might choose the way of sanity. It’s only a possibility, but at least there is that chance. Give that same kid a choice between Rap Brown and LBJ, and he’ll probably reach for his revolver.

Again, forgive the tone of this letter, Bob. But it’s not about five cent cigars and chickens in every pot. It’s about the country. I don’t want to sound like someone telling someone that he should mount the white horse; or that he should destroy his career. I also realize that if you had decided to run, you would face some filthy politics, and that there are plenty of people in the country who resent or dislike you.

With all of that, I still think the move would have been worth making, and I’m sorry you decided not to make it.

I learned later, from Newfield and others, that my letter had been placed intentionally on top of a pile of unread mail by Frank Mankiewicz, Kennedy’s press secretary. He wanted Bob to read it first. Apparently, he was moved and disturbed. For weeks, he carried it around in his briefcase, showed it to others, including those who didn’t want him to run (former Jack Kennedy speechwriter Ted Sorensen and the president’s press secretary, Pierre Salinger, among others). I knew nothing of this. I kept writing my novel, often with my daughter Deirdre on my shoulder or my lap as I typed the manuscript. I finished the draft on March 13. It was a thriller about a plot to assassinate the pope.

The next day I received a telegram from Bob Kennedy. He was taking my advice, he said. He wanted me to come home and join his campaign.

I went back to New York the following day, and my wife and children followed me a few days later. Since the California primary would be the most important of all in the time that was left, we took a rented house on top of a hill in Laguna Beach. We bought some furniture and a station wagon and moved in. After the gray damp of Ireland, the kids loved it, with the view of the vast Pacific, the walls of bougainvillea, and color throbbing with life everywhere.

Kennedy being tended to after being hit by three bullets, including one to the head. He died 26 hours later.Photo: Harry Benson

I didn’t like the life as much as they did. I had never worked for a politician before and had trouble adjusting. I liked many of the people: Adam Wolinsky and Jeff Greenfield, who wrote most of the candidate’s speeches; Mankiewicz, a son of Herman Mankiewicz, who wrote most of Citizen Kane; Fred Dutton, who was intelligent and calming when things got frantic. I wrote some short speeches that Kennedy delivered in various appearances. But the work wasn’t for me. I didn’t like the sharp elbows that were part of the life. I didn’t like the raw ambition of some of the players. I can’t remember how long I lasted. Three weeks? Maybe longer.

Then I went back to work at what I did best. I covered the Kennedy campaign for the Village Voice, and worked on my novel. I wasn’t a politician. I didn’t even want to be an exclusively political journalist. I was a writer. A generalist.

From time to time, I caught up with the campaign when Kennedy came to Los Angeles. I found my way to the campaign headquarters at one hotel or another, talked with Kennedy, or Wolinsky or Greenfield, along with reporter friends, then joined the motor caravans that went to rallies. Sometimes this wasn’t easy. The mayor of Los Angeles, a character named Yorty, seemed to hate Kennedy. And refused him police protection, in a time when the Secret Service did not protect politicians who were not yet their party’s chosen candidates. His valiant police also gave campaign vehicles more than 150 tickets. Great fella.

But in some places there was near frenzy in the air. In Boyle Heights and other parts of East L.A., the Mexican-American crowds roared in two languages and tried to touch Kennedy or hug him or kiss him. They knew that he had reached out to Cesar Chavez, who ran the farmworkers union, and Dolores Huerta, another community organizer, but there seemed to be something else at play, too, in his time with Mexican-Americans. A shared fatalism, perhaps. A sense that in the end we all die. A sense of an unhealed wound they shared over the murder of Jack. I asked, in English and Spanish, but could never get a clear answer. I just knew it was there. I could see it.

Kennedy was in Indianapolis on the evening of April 4, 1968, when word came from Memphis that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Kennedy was scheduled to speak to a large crowd in what in those days was called “the inner city.” That meant black Americans. He went to the meeting, and soon realized that most of the men and women did not yet know what had happened to King. He began to speak, without a prepared script.

“I have bad news for you,” he said, “for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is—that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight.”

His voice sounded wounded. His hair was loose in the darkening light.

“…In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black … you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization—black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another.

“Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love…

“For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man…

“My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote, ‘In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God…’”

It was an extraordinary speech, spontaneously finding language to console (and even quoting Aeschylus). That night and in the days that followed the murder of King on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, riots fueled by rage erupted in more than 100 American cities. Indianapolis remained calm. Was that because Bob Kennedy had brought to the news a proper note of sorrow and tragedy, rather than anger? We didn’t know then, and we will never know now. But in distant California, I felt a darkness growing within me, a trembling, a kind of blurry fear. Someone had managed to kill John F. Kennedy in Dallas. Someone had managed to kill Malcolm X in the Audubon Ballroom in New York. There were millions of guns in the United States, and any idiot could buy one. And it was the convention of American political campaigns that a candidate must appear in large open places or in convertible automobiles, open to the glancing embrace of those who loved him, open to a sniper’s bullet.

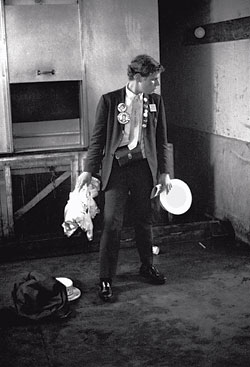

Writers Jimmy Breslin, far right, and Budd Schulberg, center, shortly after the shooter, Sirhan Sirhan, had been subdued.Photo: Harry Benson

In the days before the California primary, I traveled with the Kennedy campaign, writing for the Voice. I witnessed passion for Kennedy in many places, and passion against him. The Mexican-Americans loved him openly, without shame or embarrassment. As did the blacks we interviewed. The McCarthy people, most of them university kids, were more given to open rage, a kind of snarling middle-class radicalism paid for by Daddy, Kropotkins with credit cards. After leaving one California college (in Van Nuys), the Kennedy cars were pelted furiously with stones and bottles, most of which missed and caused other cars to swerve in jerky ways. Hitting the candidate would have been a lot easier with a rifle. The right-wing haters were quieter, more sullen, more ominous, standing with arms folded or jammed in pockets, waiting. Waiting.

And each night now, in the hour after midnight, when my wife and my daughters were asleep, I would lie in the dark thinking about the violent possibilities. Sometimes I would whisper the line from William Butler Yeats: “What made us dream that he could comb gray hair?”

On the afternoon of June 4, Primary Day, my brother Brian was going to drive the two of us north from Laguna Beach to watch the events in Los Angeles. As we pulled out onto Blue Bird Canyon Drive, my daughter Adriene, then 5, began to run after us, frantically calling “Daddy, Daddy, don’t go, Daddy.” Brian pulled over and stopped and I got out, and hugged her, and squatted down to look in her glistening brown eyes. She couldn’t explain why she was so afraid. I told her I had to go, that I was working, but I’d be back tonight, no matter what, and tomorrow we’d go to the beach. I walked her back to the house, holding her hand, until we saw her sister, then 3, who also looked anxious but said nothing. Their mother came out and took their hands. I kissed them each, and went back to the car. I kept waving until I couldn’t see them any more, but they added an ominous note to the unfolding day.

In Beverly Hills, we picked up Budd Schulberg and his wife, the actress Geraldine Brooks. We were all friends. Schulberg had founded the Watts Writers’ Workshop after the riots of 1965, and before that had written a screenplay based on Kennedy’s book about labor-union corruption, The Enemy Within. Schulberg was a passionate Kennedy supporter. He was also a true son of Hollywood (his father, B. P. Schulberg, ran Paramount Pictures when Budd was young) and remembered with fondness and laughter the times when the biggest stars flocked to the Cocoanut Grove, the fabled nightclub that was once part of the Ambassador. Then Brian parked the car and we all went into the lobby, glanced at the crowded Embassy Ballroom, where Kennedy would eventually make a speech about victory or defeat, and then took the elevator up to the fifth floor.

By 11 p.m., it seemed clear that Kennedy had won California, a huge triumph that would erase the comparatively minor shame of defeat in Oregon. Now we were in Kennedy’s own room: Schulberg, Brian, Cesar Chavez, Newfield, Breslin. I remember squatting with my back against a wall. Kennedy was on the floor, back to a sofa, one arm resting on a raised knee, the other leg stretched out. Others came and went. Frank Mankiewicz handed him a sheet of paper. Maybe words for a speech. Maybe more results. The TV set was on, the sound off, showing Kennedy ahead. Most people had glasses in their hands. Beer. Harder stuff. Soft drinks.

The mood was light, almost giddy. Kennedy smiled and smiled, and laughed out loud at Breslin’s interminable New York joking. Then someone said, glancing at a watch, that it was time to go down. Kennedy stood up, buttoned his cuffs and his collar, went into the bathroom. Everybody else was standing now. Some went back to the larger room across the hall where television might offer a better view. Kennedy came out of the men’s room. He had combed his hair and donned a jacket. He was smiling broadly.

“Let’s go down,” he said.

I was pushed with others to the small bandstand where Kennedy would talk. I was beside George Plimpton in the back row. There were drapes behind us, and we both tried opening them and discovered there was no wall behind the drapes. It was about a two-foot fall. “For God’s sake,” Plimpton warned everyone else, “don’t lean on the drapes.” Kennedy arrived, Ethel beside him, and moved to the microphone. He could see hundreds of red and blue balloons rising toward the gilded panels of the ceiling and the three immense chandeliers. Young women wearing plastic Kennedy boaters were chanting, but in the general din, I couldn’t hear the words. I counted eleven television cameras aimed at the stage, and more still photographers, including my brother Brian, moving through the sweaty human stew. Kennedy began speaking.

A campaign worker standing in the spot where Kennedy fell.Photo: Harry Benson

“I’d like to express my high regard for Don Drysdale,” he said. The great Dodger pitcher had just won his sixth straight shutout, and the room roared. Kennedy smiled broadly and said: “I hope we have his support in this campaign.” He thanked the football player Rosey Grier and the decathlon champion Rafer Johnson, who were indeed part of his campaign. He thanked the Democratic boss Jesse Unruh, who was given timid cheers, and Cesar Chavez, who got huge cheers, and then thanked the staff and the volunteers and the voters, and the ballroom crowd cheered mightily for all of them. The California victory was not definitive. The nomination would have to be settled now in August, at the Democratic convention in Chicago. But if Kennedy had lost in California, he would have been finished.

“I thank all of you,” he was saying now. “Mayor Yorty just sent a message that we have been here too long already.” Loud laughter. “So my thanks to all of you and now it’s on to Chicago … ”

Kennedy thrust a thumb in the air, brushed his hair, made a V with the fingers of his right hand. The crowd was chanting now. “We want Bobby! We want Bobby! We want Bobby!” Plimpton and I went down three steps off the side of the stage, through a gauntlet of Kennedy volunteers and brown-uniformed private security guards. We turned left. At the other end of the stage, people turned right. On to Chicago. On to Chicago …

We entered a long grungy area called the pantry. I would write later that it was the sort of place where Puerto Ricans, blacks, and Mexicans usually worked to fill white stomachs. Fluorescent ceiling lights, bare sandy-colored concrete floors, pale dirty walls. A rusting ice machine. Shelves filled with dirty glasses. Through an archway to the left, we could see the main kitchen. A small group of Mexican-American cooks and busboys waited for Kennedy. To shake his hand. To murmur about luck, and thank him for coming. Against the left wall, three steel serving carts stood end to end. At the far end of the long pantry, two doors led to an improvised pressroom where Kennedy would speak to the press about the primary.

Kennedy moved slowly into the area, shaking hands, with people from the stage behind him, at the head of a platoon of reporters, photographers, campaign staffers, TV men, and the curious. I was walking backward, facing Kennedy, scribbling notes. I saw him turn to his left to shake hands with a smiling young Mexican man (we learned later that his name was Juan Romero). From the Embassy Room we could still hear chants.

“We want Bobby. We want—”

Then a cruel messenger arrived. Curly-haired. Pockmarked face. In a pale-blue sweatshirt. Blue jeans. His right foot was forward. His right arm was straight out. He was firing a gun.

A ferocious brawling moment: Grier, Plimpton, Rafer, Schulberg, me. Others. All of us trying to get the gun. The pockmarked young man still firing, so that some people behind Kennedy were hit in the legs. Then the gun was out of the man’s hand, and he was being lifted, slammed onto the line of steam tables, dragged toward the exit to the pressroom, someone yelling, “Don’t kill him, don’t kill him, no Jack Ruby!”

And there was Kennedy on the floor, at the foot of the ice machine, his eyes open, a kind of sweet accepting smile on his face, as if he knew it would all end this way. There was blood on the fingers of his right hand, and blood on his chest, so I thought he had been shot just below the neck. But because his head had been turned to say hello to Juan Romero, the first shot hit him behind the right ear and his hand brushed reflexively at the wound as he crumpled to the floor.

Ethel came to comfort him, and seemed to know that he was forever beyond comfort. Juan Romero came to him too, as shown in the extraordinary photographs Bill Eppridge made in that awful pantry. My notes told me later that Kennedy was shot at 12:10, and was carried out of that grubby kitchen at 12:32. It seemed a lot longer.

Brian and I ran outside the hotel. A large enraged black man was heaving chairs into the swimming pool. Another was punching a hotel pillar with a bloody right fist. Weeping Kennedy volunteers were all around us. We kept hearing a single word, repeated in many variations. Why? Why? In my own head, I blamed some dark hole in American life, but I was wrong. The origins of this killing—for Bob was sure to die in a matter of hours—lay in the Middle East. The gunman was a Palestinian immigrant named Sirhan Sirhan. He was 24. His rage was fueled by the Six-Day War the previous year and by Kennedy’s support for the sale of jet fighters to Israel. The motives didn’t truly matter. The crucial fact was simpler: He was able to get a gun. Brian and I drove to the Good Samaritan Hospital, where Kennedy was dying in a room on a high floor.

Early in the morning, Brian drove south in the California night. I dozed and felt sick. When we came through the canyon into Laguna Beach, I could see the colors of the sky warming as the sun pushed over the mountains. Flocks of birds were rising from the darkness. We reached the house and I went in and turned on the television set and looked at the latest bulletins. I sat facing the set and the sea. Brian and I drank some whiskey and then he went off to sleep. I looked up and saw my daughter, Adriene, staring at me in a baffled way. My face must have been a ruin. She came over to me, tears in her eyes, and touched my face. I started to weep for her, for her sister, for my Irish parents, for my friends, for America. Out there. Sea to shining sea. I held her tight, wondering what would become of all of us.

SEE ALSO

• Pete Hamill on the Death and Life of John Lennon

• New York’s 40th Anniversary Coverage: Classic Stories by Hamill, Tom Wolfe, Gloria Steinem, and more.

This essay is excerpted from the introduction to the forthcoming book A Time It Was: Bobby Kennedy in the Sixties, photographs and text by Bill Eppridge, published by Abrams. Copyright © 2008 by Pete Hamill.