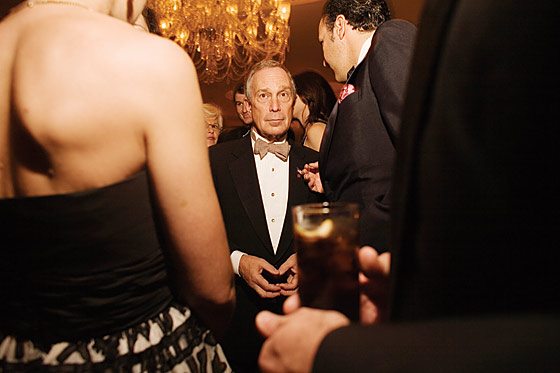

Tonight’s dinner party is in honor of London mayor Boris Johnson. Nominally, anyway. Like every gathering on the fifth floor of an ever-expanding townhouse on East 79th Street, this event is really in honor of its host. Mayor Michael Bloomberg doesn’t just live here—he presides here. Beginning in the days when he ran Bloomberg L.P., the multinational financial-information juggernaut he founded, Bloomberg has used dinner at his home to surround himself with the city’s elite, soliciting ideas and amusing anecdotes and ingratiating himself with the old-line power brokers who would eventually help him gain—and keep—City Hall. Since Bloomberg was first elected mayor in 2001, his guest list has stretched to include less-glamorous types—public-school teachers, union leaders, novelists. This is the inner sanctum of the meritocracy, and the mayor is an equal-opportunity inviter. But always the affairs are arranged to maximize the benefit to the host.

Johnson is in New York to promote U.K.-U.S. tourism. Bloomberg is a longtime Anglophile, and his company’s second-largest office is in London. The clearest sign that this Sunday evening holds special resonance for Bloomberg is the presence of Rupert Murdoch, Mort Zuckerman, and Arthur Sulzberger Jr., the publishers of New York’s three daily newspapers. They’re here because Bloomberg asked them to be. “Those three are at anything that really matters to Mike,” a dinner-party veteran says.

After cocktails on the second floor, the guests walk up to the fifth floor and find their chairs at one of the small tables. Bloomberg circulates throughout the evening, working his way from one table to the next. Katie Couric is here, and Emma Thompson, and Ken Chenault, the CEO of American Express. There’s Dan Doctoroff, the Bloomberg deputy mayor for economic development turned president of Bloomberg L.P. Each guest is a significant player in his or her own realm—wielding the power of celebrity or the power to swing elections or to move markets. Yet wherever he mingles, the 67-year-old Bloomberg eclipses his guests. Not because he is worth far more money than any two of the corporate tycoons put together; that’s been true for years. It’s because in the past seven years Michael Bloomberg has become the only powerful figure in New York who really matters.

This magazine pioneered the power list way back in 1968. In stories with headlines like “The Power Game” and “The 36 Who Run New York,” the writers Ed Costikyan, Nick Pileggi, Richard Reeves, and Dick Schaap constructed not just a numerical ranking of the city’s movers and shakers but a vivid tapestry of how those players—many of them unelected and obscure—interacted to shape public life in New York. The specific names that made up the Establishment changed over time, thanks to deaths, indictments, newly made fortunes, and the election cycle. But one thing about the New York Establishment stayed true for a solid decade: the multiplicity of actors with real sway over civic life.

No more. Forty-one years later, there is a one-man Establishment: Michael Bloomberg. Certainly there are other figures with real power. But in a way that wasn’t true two decades ago, their influence is circumscribed, confined to their narrow categories: real estate, culture, health care, banking. And, in terms of civic life, little of their power exists independent of their relationships with Bloomberg. The mogul-class push for the mayor’s term-limits extension felt like the last gasp of what’s left of the city’s old-line ruling class.

The mayor is not a dictator. He can’t unilaterally decree major changes, and he still has to strike bargains with two legislative bodies—the City Council (generally a formality) and the State Legislature (more difficult, particularly when dealing with the inscrutable Sheldon Silver). But Bloomberg gets what he wants more than any mayor in modern memory.

The foundation of Bloomberg’s imperial mayoralty is, obviously, money. He’s used his vast personal fortune—$17.5 billion at last Forbes estimate—relentlessly and creatively to reverse the standard political dynamic: Instead of the special interests’ buying off the politicians, the city’s top politician has bought off the special interests. Money has allowed him to create the Bloomberg Party, whose clubhouse is the business elite and whose field troops are enlisted issue by issue. Bloomberg employs large segments of the city’s political class, directly and indirectly, and his philanthropy, often done in secret, gives him a very large circle of friends. Opposing him can be an exceedingly lonely occupation.

The mayor has also been lucky, benefiting from historical trends that have sidelined or crippled many of the city’s traditional power centers. “There’s been a major shift in the power structure in a short period of time,” says real-estate baron and Daily News publisher Mort Zuckerman. “It’s hard to name many major players. Some of it is because of what’s happening in the financial world. But much of the shift is because the mayor is so predominant.”

Bloomberg’s aura of managerial effectiveness—he earned that fortune, after all—has smoothed the way in many of his endeavors. After the tumultuous Dinkins and Giuliani decade, the comparative peace of the Bloomberg years—albeit accompanied by the incessant sounds of construction—has been more than welcome. His social-issue sensibilities—pro-immigration, anti-gun—line up tidily with the city’s liberal mainstream. And his signature accomplishments, like taking control of the school system, have been easy to sell as sensible reforms, no-brainers opposed by troglodytic vested interests. In many ways he’s been a very good mayor. And yet there’s an inescapable queasiness in the city as the mayor proceeds through the democratic formalities and prepares—barring a huge upset win by Democrat Bill Thompson—for a third term. Bloomberg’s successful campaign to rewrite the term-limits law—using his connections and his money, he artfully circumvented bringing the matter to a public referendum—is precisely what, in a democracy, should not be possible, no matter what one thinks of the ends.

Back in 1999, when Michael Bloomberg began to think about a career change, his mogul friends were amazed. Bloomberg had at that point been a CEO for more than seventeen years. Why would he want to submit himself to the grubby rituals of campaigning, especially the media hazing? Still, the business class quickly came aboard, based in part on a sense of its own managerial excellence—who better to lead the city than a tycoon?—and in part on the fact that his agenda is theirs: growth and more growth.

Bloomberg made it clear from early on that even among his business peers, the lines of authority would be clear. Not long after Bloomberg won control of the public-school system, he was tested by Randi Weingarten, then the head of the teachers union. Weingarten was fighting with Joel Klein, Bloomberg’s school chancellor. But instead of complaining to Bloomberg, who had consistently backed Klein in other battles, Weingarten tried to enlist business-world intermediaries she thought Bloomberg would be more inclined to listen to sympathetically. Bloomberg was angry at the maneuver and sent a clear message of his own. “For business leaders, stepping forward and trying to become a civic leader would be at some risk to your relationship with the mayor,” a corporate insider says. “Only a crazy person would step out without Bloomberg’s say-so.” (Weingarten says she doesn’t remember the episode.)

As Bloomberg has moved to consolidate his clout, the hubs of power in the city have shifted, in some cases with extreme swiftness, and these changes have tended to work in the mayor’s favor. When Bloomberg took office in January 2002, Dick Grasso, the head of the New York Stock Exchange, was not just a colorful, well-known personality but a force in the city’s financial life. Quick: Name the head of the NYSE today. The stock exchange, as an institution, was going through a radical reshaping even before the recession. (The answer, by the way: Duncan L. Niederauer runs what’s now called NYSE Euronext, after a desperate 2007 merger with the European stock market.)

The recession has also wreaked havoc with the city’s power elite, virtually leveling what seemed only a few years ago to be unshakable edifices. The board of directors of the Partnership for New York City has been a reliable roster of the city’s business Establishment since it was created in 1979 by David Rockefeller. The Partnership’s board has taken a large blow in the past year, losing stalwarts from AIG and Merrill Lynch, but it retains big names like Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs and Larry Fink of Black Rock. The Partnership’s director, Kathy Wylde, has noticed another far-reaching structural evolution. “One huge change in the power structure is that increasingly the locus of power is external, not local,” she says. “Purely local business leaders are not as relevant as they used to be, because it has become a global economy. David Rockefeller was a local leader, because he ran a bank that was American and local. Today, more than half the revenue of any New York bank is from overseas.”

So instead of Walter Wriston, who as head of Citibank in the sixties and seventies was also deeply involved in steering the city’s finances, today’s city banker is typified by Jamie Dimon. He’s a native New Yorker and a committed member of all the right boards of local charities. But Dimon’s focus is necessarily outside the city, and that was even before he and JPMorgan Chase became one of the last megabanking survivors. Dimon and the others still employ thousands of New Yorkers, and their companies contribute millions in tax revenues to the city budget. But New York’s CEOs need to devote most of their attention to the world beyond the Hudson, and their political focus is Washington. “It’s not just that we’ve lost Lehman and Bear Stearns; it’s that Morgan Stanley and Citi are very different from what they were, and a lot of hedge funds have changed as well,” Zuckerman says. “The financial industry hasn’t lost its leverage in the city—and maybe that’s the wrong word to use at the moment—but it certainly has changed, just as the city’s legal world has. Guys like Howard Squadron or Bill Shea were political operatives as much as they were attorneys, and there aren’t any rough parallels right now. Publicist Howard Rubenstein is still a factor, but it’s hard to name many other players. In real estate, Jerry Speyer was a power player, and still is, but he’s distracted. Everyone is right now.” In these turbulent financial times, the business elite has been more than happy to delegate the job of running the city to one of their own.

A generational shift has also enhanced Bloomberg’s power. As some of New York’s biggest players have passed the baton—from Jerry to Rob Speyer, from George to Hal Steinbrenner—the pattern has been that the son is a paler version of the father, confronting a rougher business climate.

Bloomberg talks to a wide range of other leaders, and has genuine respect for many—among them Dick Beattie, the Simpson Thacher senior partner who launched the New Visions charter-school program; Nat Leventhal, the old Ed Koch hand and recently retired president of Lincoln Center; and Chuck Schumer, the U.S. Senate dynamo. But who can tell the mayor that he’s wrong, that he has a bad idea or is making a big mistake, and be taken seriously? “No one,” a Bloomberg intimate says. “He doesn’t really listen to anyone.”

While Bloomberg’s wealthy peers have willingly acquiesced, other actors have needed to be finessed, which the mayor has done with a political shrewdness that few would have predicted he possessed when he was first elected. Two days after he’d squeaked past Mark Green in 2001, Bloomberg gripped and grinned with the Reverend Al Sharpton at a dinner for 100 Black Men. It seemed to be a chance encounter, two prominent New Yorkers at the same event, but in fact it was a highly staged handshake, choreographed by Bloomberg himself to send a message: He was no Rudy Giuliani, who fought first and talked later, if at all. The city was once again being run by a mature adult. Bloomberg made sure a photographer was present, and the next morning the shot was on the front page of the Post.

Sharpton appreciated Bloomberg’s early gesture of respect, as well as the ongoing efforts by the mayor and his staff to keep the lines of communication open. Recently, Sharpton has become partners with Joel Klein in an initiative to close the performance gap between white and black and Latino schoolkids, further drawing him into Bloomberg’s orbit. So even when Sharpton has expressed differences with the mayor over the years, he’s kept his complaints civil, one payoff from Bloomberg’s charm offensive. And he sounds stunned when describing how other elements of the traditional opposition have fallen away.

“It’s an interesting time,” Sharpton says. “It’s the first time you have a mayoral election and you can’t identify by name two labor leaders who are known citywide. It’s the same in other civic groups.”

Two of the biggest union names and personalities—Weingarten of the teachers union and Dennis Rivera of SEIU 1199—departed for Washington jobs, and their replacements have so far shown little inclination to clash with the mayor. Even before the turnover, Bloomberg’s squabbles with the unions seemed almost ritualistic. The real-estate and stock-market booms, and the property-tax hikes instituted in 2002, allowed the mayor to forge a new bargain with organized labor; it’s fairly easy for a mayor to keep the labor peace when he’s handing out meaty wage increases to city workers. The average salary paid to teachers, for instance, is up 43 percent during the mayor’s two terms, without significant progress in work rules.

A remarkable number of dominoes have fallen Bloomberg’s way. The city’s ethnic politics are at a transition point: Black activists trained in the civil-rights model are fading, and though the city’s Latino and Asian communities have rising population numbers, they have yet to coalesce around any leaders, though the primary victory of John Liu is perhaps a sign of things to come. The speaker of the City Council is usually a mayoral antagonist. But the current speaker, Christine Quinn, decided that the best way to be elected mayor herself was to ingratiate herself with Bloomberg. Then Quinn was further neutered by the council’s slush-fund scandal.

Bloomberg has also been fortunate to be mayor at a time when the local press has been reeling. Individual City Hall reporters and bloggers remain diligent and skeptical in their coverage. But there’s no Jimmy Breslin or Jack Newfield or Andy Logan on the scene—a columnist with the moral standing and the readership to make City Hall nervous. Bloomberg’s company is one of the very few media operations that are still expanding, which feeds conspiracy theories that the city’s media have pulled their punches when covering the mayor. The reality is less exciting but equally depressing: that local papers and TV stations, hemorrhaging money, are devoting ever fewer resources and follow-up to city politics.

On a gray October Saturday morning, candidate Bloomberg drops by the Fairway supermarket in Red Hook for some retail—in both senses of the word—campaigning. He looks elfin, barely five-foot-six and stoop-shouldered, wearing a tangerine-colored V-neck sweater so bright it practically vibrates. He’s charming and self-deprecating, much more the natural politician than when he’s on a podium. Bloomberg accepts hugs from customers and passes along anecdotes about the children of immigrants who have been accepted to Ivy League colleges, a reminder that at bottom Bloomberg is a world-class salesman. He smiles broadly when a local developer says that Fairway has hired 100 more workers than planned. Bloomberg chats with shopper Brian O’Connell, 41, a research executive at Dow Jones; the mayor says he’s discussed with “Rupert” the ways in which their competing companies face similar problems. “Bloomberg has been an excellent mayor,” O’Connell says later, while he and his wife bag their groceries. “He cares about the things we do: education, the environment. And he’s a great fit for New York because he’s a success, but not in something like a chain of dry cleaners. He’s a success in finance and the media, which fits the city’s self-image. I wouldn’t say this about another politician, but the risk isn’t that he has too much power. It’s that you have a mayor who doesn’t have enough power and can’t get things done.”

A couple of lanes down, a young female cashier cries out. “Bloomberg is here?” she says excitedly. “Do I get a million dollars?”

The two random moments neatly encapsulate how it feels to live in Bloomberg’s New York. Through his company or his mayoralty, Bloomberg permeates every facet of city life, from the financial charts you’re studying to the healthier fat you’re eating to the skyscraper you’re welding. Bloomberg shares an appeal with that of Starbucks: the satisfaction of associating with an upscale product, even if our standard of living is declining. And many of us aspire to the mayor’s power, or at least a piece of his bank account.

Bloomberg has certainly deepened the financial bond—or dependency—through the strategic use of his checkbook. His charitable contributions have increased exponentially from when he first decided to run for mayor. In 1999, he gave away $47 million; last year, the figure was $235 million. Some of the money is funneled through the Carnegie Corporation, as supposedly anonymous gifts. Last year, 542 New York charities and nonprofits received $60 million of such gifts.

Money is a stealth weapon in Bloomberg’s political arsenal. And, as fund-raiser-in-chief, the mayor can leverage his own giving by tapping his well-heeled associates. “The mayor has an enormous influence in charity, and he does so much of it anonymously,” Rubenstein says. “I talk to some of the institutions who are clients and I say, ‘Why don’t you appeal to the mayor for money?’ They say, ‘What do you mean, appeal? He’s been funding us for years!’ I just had that discussion a couple of days ago with one of my museum clients.”

Bloomberg has also ramped up his purely political spending. Some of it is surreptitious: In 2008, three of Bloomberg’s closest friends and business associates suddenly wrote checks for $50,000 to the Working Families Party. The money was then steered to State Senate candidate Daniel Squadron, who’d won Bloomberg’s endorsement in a race to unseat a longtime incumbent.

The mayor’s dance with the Independence Party provides perhaps the best illustration of his creativity with cash. In 2001, Bloomberg attracted a crucial 59,000 votes on the Independence Party line. Four years later, he wrote a check for $250,000 and was once again rewarded with its slot, giving guilty Democrats a place to vote for Bloomberg in 2005. The cost at least doubled this year, with Bloomberg receiving the Indy and Republican ballot spots after making donations of $250,000 to each.

Lately, the Working Families Party has become a threat, so Bloomberg has used the Independence Party as even more of a conduit. In 2005, Bloomberg kicked Tom Ognibene out of the Republican mayoral primary by challenging his petition signatures. Next month, however, Ognibene will appear on the Independence ballot line thanks to Bloomberg’s blessing—because Ognibene’s opponent for a Queens City Council seat is a WFP-backed incumbent.

In mayoral-campaign seasons, Bloomberg’s wealth has a double-sided impact: He enjoys the ability to spend unlimited amounts of his own money on his reelection, and groups grateful for Bloomberg’s private donations have ample reason to support him politically, or to at least remain neutral, even though the mayor says he goes out of his way to avoid conflicts of interest in his giving. “100 Black Men came to New York for their national convention several months ago, and the national organization should be psyched that a black man is the Democratic nominee for mayor of New York City,” a Thompson operative says. “Nope; they told us they’re not interested in supporting him. Why? Could it be because Bloomberg’s company has given them money?”

Bloomberg’s wealthy friends aren’t going to be disloyal, either. Many of them have, in the past, been reliable Democratic donors. This year, though, more than 160 people who maxed out their contribution to Bill Thompson’s 2005 comptroller campaign have given him exactly zero to run for mayor against Bloomberg. The mayor’s campaign fixes the blame elsewhere. “Mr. Thompson’s fund-raising numbers are anemic because not enough people think either he should win or will win,” says Howard Wolfson, Bloomberg’s campaign communications director. “In the age of the Internet, he shouldn’t need wealthy people to raise money for him.”

Wolfson, who came up through the Chuck Schumer farm system and last year helped run Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, is a prime example of how Bloomberg has been able to deprive his Democratic rivals of campaign talent. Designing Bloomberg’s current get-out-the-vote ground game is Maura Keaney, whom he hired away from City Council speaker Christine Quinn. Bloomberg’s longtime lead political strategist, Kevin Sheekey, has stayed in City Hall this time around, tending to his job as deputy mayor for government affairs, but his vision still suffuses the Bloomberg campaign operation. Sheekey believes in the Colin Powell doctrine: Bring overwhelming force.

Which fits perfectly with the style of Sheekey’s patron. Four years ago, Bloomberg was blunt: He didn’t care about the abstract notion of campaign-finance equality—he cared about winning. “What’s the argument to run a risk?” he asks. “If you really believe that you’re making a difference and that you can leave a legacy of better schools and jobs and safer streets, why would you not spend the money? The objective is to improve the schools, bring down crime, build affordable housing, clean the streets—not to have a fair fight.” Whether you agreed with that philosophy or not, at least Bloomberg was willing to talk about it. This time around, the mayor will only sit down with the editorial boards of the papers.

Bloomberg’s partisans say the reason for the burgeoning of his power is simple: He’s done a good job. “Mayors aren’t powerful because they aren’t successful, because they couldn’t close the deal, because they couldn’t run the city,” Sheekey says. “It’s your ability to deliver public safety, trash collection, all the basic parts of the job.”

Bloomberg does indeed deserve credit for the good things that have occurred on his watch. Crime rates have remained at record lows, and there hasn’t been another terrorist attack; the reasons for both are multifaceted, but Ray Kelly and the NYPD have been energetic in the pursuit of bad guys, though sometimes at the expense of civil liberties. Bloomberg’s smoking ban will save thousands of lives and cut millions from medical bills, and not just in New York. The mayor has nurtured the city’s biotech sector, as part of his plan to diversify the city’s economy.

Bloomberg’s management of the city’s budget has generally been astute, particularly his unpopular push to raise property taxes in the months after 9/11 and his insistence on setting aside money during the good times and paying down some of the city’s debt. But his budget record overall is mixed. “For most of his two terms, the mayor has followed along with the business cycle: He did pattern bargaining with the unions when times were good, he gave wage increases above the rate of inflation, he kicked up city expenses and pensions,” says Carol Kellermann, president of the Citizen’s Budget Commission. “And he did a lot of ambitious capital spending.” As a result, the city’s budget has grown from $41 billion to $59.5 billion this fiscal year, according to the Independent Budget Office, and a reckoning looms. The mayor has also been unable, despite devoting lots of rhetoric to the subject, to wean the city from its dependence on Wall Street revenue—though to be fair, any mayor has only tangential influence on the city’s mix of private employment.

Where Bloomberg has been especially savvy is in defining the terms of success for his management of the schools. He points emphatically to higher state test scores and graduation rates—but whether those numbers measure real learning or merely a facility in taking tests is impossible to tell.

Bloomberg’s lieutenants dismiss the notion that he has any greater power than previous mayors, or that the altered landscape has given him an advantage.

“The same power structure is more or less here,” says Ed Skyler, who started as Bloomberg’s press secretary and has risen to deputy mayor for operations. “I don’t know that I have seen it shift. What you have seen is someone come on the scene who didn’t have a public-sector profile eight years ago that has now been mayor for two terms and who knows how to work with all the sectors. He knows how to get a rezoning done, by working with the labor unions and with developers. He knows how to support the tourism industry. He knows what the city needs to be a financial powerhouse. So you see a mayor who is equally comfortable in a diner in Jackson Heights as he is in a corporate boardroom, because he’s spent time understanding everybody’s issues, from small businesses to big business, teachers, cops.”

In this view, that agenda advances because of its indisputable virtue, the unassailable merits of his ideas, not because Bloomberg greases the system with money. “So many compromises are made in politics, so much access is involved, so many decisions are made, through money,” Sheekey says. “This mayor gets to make decisions in a much freer manner. People used to talk about the mayor’s money initially—‘Oh, he’s got all this money, he’s going to buy an election.’ But no one could ever really point to any system of success of politicians being able to buy elections. Look at Mike Bloomberg and Jon Corzine. Very similar backgrounds, very similar people. Both came into office spending a lot of money, okay? And one of them has been very successful, and one has generally been very unsuccessful, both in competitive environments. Why is that? I would argue it’s because one turned out to be really good at his job, and is surrounded by really good people, and he’s used persuasion to move things forward. If Mike Bloomberg were unsuccessful, he’d be a one-term mayor.”

True. But Mike Bloomberg is on his way to being a three-term mayor. And the way he accomplished that raises questions that will taint his legacy, no matter what history’s verdict is on his stewardship of the city. After all, no one ever said that one-man rule is a necessarily ineffective form of government. Pondering his anti-democratic methods, even voters who admire his competence may think twice before pulling the lever.

On September 12, 2008, Bloomberg sat on a small sofa in an ornate private office inside City Hall; next to him was a small pillow inscribed DO NOT START WITH ME. YOU WILL NOT WIN. In a nearby wing chair sat Ed Koch. The two men spent an hour comparing their years in office, covering all the serious challenges: race relations, union-contract negotiations, the awfulness of breaking bad news to a police widow. Near the end of the conversation, the talk turned to who’d occupy City Hall next. Back then, the speculation as to whether Bloomberg was going to go back on his word and try to overturn term limits had gone from incredulous to fevered. In press conferences, the mayor had grown increasingly testy and dodgy on the subject. Today, however, he played off a question about whether he was planning to run again in 2009, turning it into a joke. “My candidate is sitting right here,” Bloomberg said, smiling at his predecessor. “I’m going to work hard to convince Ed Koch to run. And if he is not willing to run, I don’t know the answer.”

Maybe, somehow, Bloomberg really hadn’t made up his mind. The business elite had begun lobbying for Bloomberg to stay on as far back as 2006, long before any financial crisis loomed on the horizon. Jerry Speyer and Henry Kravis chatted up Ron Lauder, the cosmetics billionaire and sponsor of the city’s term-limits legislation in 1996, about agreeing to a onetime extension of term limits. Lauder said no, but at that time his intransigence was less important than Bloomberg’s lack of interest: He didn’t want to stay mayor, he wanted a promotion to the White House. The demise of Bloomberg’s presidential dream in February 2008 left him more open to third-term suggestion, and in June, he commissioned a poll to test public opinion.

Then the events of that mid-September weekend gave Bloomberg the cover he needed, emotionally as well as politically. Down in Washington, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and other government officials decided to let Lehman Brothers collapse. When Bloomberg found out, on Sunday, he was strangely upbeat, canceling a scheduled trip to California and preparing to jump into the action on Monday morning, when he knew the stock markets would convulse. “There was a spring in his step, because he recognized it was a crisis,” a senior aide says. “These guys—Paulson, Geithner—were reaching out to him: ‘What do you think?’ It totally energized him.” After months of brooding about his upcoming forced retirement, Bloomberg believed he wasn’t simply needed again; he was indispensable to the city’s survival.

It took several more weeks to make Bloomberg’s grab for a third term official, but the campaign had been under way for months. Much of the mogul class had been encouraging Bloomberg, appealing to his sense of himself as above politics, telling him that the city couldn’t afford a return to old-style Democratic rule. At first Bloomberg was in favor of a different strategy: Handing off City Hall to a like-minded plutocrat, former Time Warner CEO Dick Parsons. But Parsons rebuffed Bloomberg, and soon the mayor was methodically aligning support to help make the case for a third term. Zuckerman and Murdoch required little persuasion. In fact, Bloomberg needed to restrain Murdoch’s enthusiasm when the Post’s owner wanted to print a “Run, Mike, Run” editorial in mid-September 2008. Over dinner at an Upper East Side Italian restaurant with Murdoch and Rubenstein, Bloomberg urged patience. For one thing, he needed to get the Times on his side. The paper had editorialized its vehement opposition to Giuliani’s bid for a post-9/11 term extension. But Bloomberg’s close friend Steve Rattner, the investment banker and former federal car czar, is also a longtime friend of Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger, and eventually the Times editorial page threw in with the mayor.

Ron Lauder seemed to back down from a threat to bankroll TV ads supporting term limits. Then, days later, Lauder equivocated. Bloomberg, on a trip to London, publicly claimed to not be paying attention to the controversy back home. Privately, he was furious, and when he returned to New York, Rubenstein brokered a Gracie Mansion sit-down between the mayor and Lauder. “If Ron Lauder wanted to put $10 million into a campaign to keep term limits, that might have had a significant intellectual and emotional impact,” says Rubenstein, whose public-relations firm has represented both Ron and his brother Leonard, the chairman emeritus of the family’s Estée Lauder company. “The mayor wanted to avoid a knockdown, drag-out, wild fight. Ron Lauder saw the economy in what he thought was a pretty big free fall, and he’s a businessperson. We discussed that—who would our best bet be at this most important decision to be mayor?” A deal was hammered out: Lauder would drop his opposition in exchange for the promise that this would be a onetime extension, exclusively for Bloomberg, and that Lauder would be included in a future review of the term-limits law. “It wasn’t about principle,” a Lauder acquaintance says. “It was a matter of attention being paid to Ron.”

Even if the cause was unseemly, the execution of the political strategy to rewrite the law was staggeringly impressive, enlisting Bloomberg’s moneyed friends and the friends he’s made with his money and displaying an impressive eye for detail. An ethnically diverse cast of average citizens appeared in the front row at the council hearings, clutching preprinted signs reading democrats for choices. Bloomberg campaign aides like Patrick Brennan were suddenly “volunteering” their time to round up supporters to pass the needed City Council bill extending term limits. When Linda Gibbs, the mayor’s head of Health and Human Services, lobbied an official at a social-services group to make calls to council members, there didn’t seem to be much choice. The mayor’s operatives coaxed a wide range of recipients of his charitable donations to testify, but most were smart enough that they didn’t need an invitation. The Public Art Fund has received at least $500,000 from Bloomberg; its head, Susan Freedman, spoke enthusiastically on the mayor’s behalf—and, she says, with a clear conscience because of Bloomberg’s belief in the importance of the arts. “Do you think you would need to twist my arm to have me want this kind of leadership continue?” she said afterward.

The parade of witnesses included Mario Cuomo, the former governor, who is now of counsel to Willkie Farr & Gallagher, the firm that is defending Bloomberg L.P. against sexual-discrimination lawsuits and that has as one of its top partners Richard DeScherer, Bloomberg’s lawyer. Geoffrey Canada, who runs the Harlem Children’s Zone, spoke of his worry for New York’s most vulnerable during the downturn. He didn’t mention that his organization has city contracts worth millions of dollars and has received more than $500,000 in private money from Bloomberg.

“It’s a legitimate question, to ask about people being compromised,” Canada says. “But everybody knows we get money from the city! We have since the seventies. I wouldn’t turn down money from anyone who wants to support our programs. But is my vote for sale? Absolutely not. I’m very comfortable with the real reasons I’m supporting Bloomberg—his attention to education, the reduction in crime without the rancor of the Giuliani years, and his fairness in spreading the budget pain.”

A year later, the change looks like a brilliant seizing of the moment by Bloomberg—and like weak-kneed overreaction by his enablers. True, the city’s economy has continued to slump badly, but it hasn’t shattered. The mayor claims credit for things not being worse, and he deserves some of it, particularly for cutting the budget in advance of last fall’s gyrations and then trimming some more this spring without inflicting excessive damage—with the crucial, though temporary, help of federal stimulus money.

But that’s only become clear lately. The reelection campaign, Bloomberg’s $100 million version of economic aid, was already in full swing.

Each year for more than a decade, beginning in the sixties and stretching through the early eighties, this magazine’s power list described the gradations in weight of a dozen or more major players, all of them with significant juice. With one enormous exception. Looking back at 1972, and previewing the year to come, Richard Reeves wrote, “The names on this list are formidable people, but none of them—not even all of them combined—means as much as Nelson A. Rockefeller.” Thirty-six years later, the parallels are uncanny—an exceedingly wealthy man in a top elective office, using his own money as well as the tools of his job to dominate a weakened civic hierarchy—even if the details are different and the valences are reversed: Rocky was a strong governor stepping in to clean up for a hollow mayor (the post-presidential-campaign John Lindsay); Bloomy is a strong mayor who wishes he could clean up for a hollow governor (indeed, David Paterson’s weakness only augments the mayor’s power). But perhaps the greatest difference is that Bloomberg’s power outstrips Rockefeller’s by a wide measure, wider even than the gap in their wealth: Bloomberg, New York’s richest man, is approximately twelve times richer than Rockefeller, in today’s dollars, and he’s spread his money around more craftily and more extensively than Rocky ever did.

Which is why the words of Reeves’s final paragraph, applied to a different man, hold true all these years later. “He says that we need him, that he will save the city. That may even be true. God knows we have him whether we like it or not.” This time, though, the story is likely to end differently: Rockefeller, deciding he had nowhere to go but down and determined to run for president again, resigned as governor in December 1973, leaving the state in the hands of the estimable Malcolm Wilson. Perhaps Bloomberg still pines for the presidency. But you don’t amass all this power, and spend $100 million to hang on to it, to prematurely surrender the job to Bill de Blasio. Instead, the mayor is agitating to eliminate the office of public advocate even before De Blasio has officially been elected. If Mike Bloomberg is going to stick around until 2014, he wants to have all possible power at his disposal. How he uses that power can’t completely efface the fact of how he gained it.

See the List

The Power Dozen