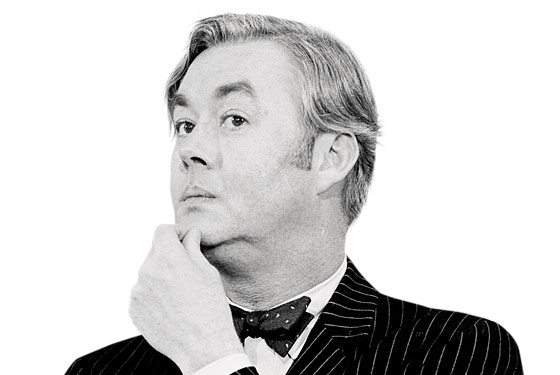

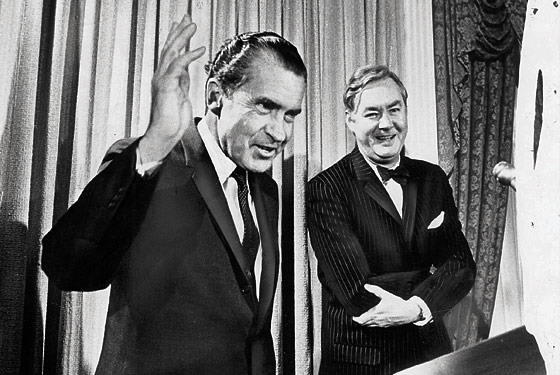

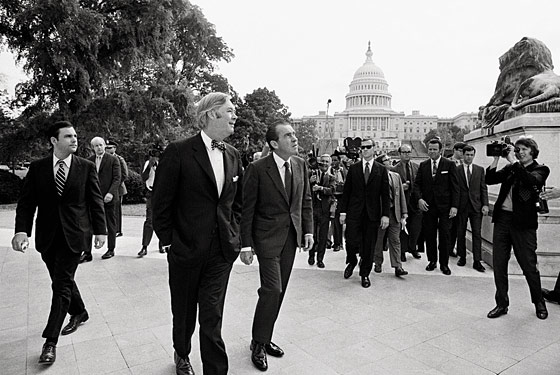

Daniel Patrick Moynihan served four presidents (from Kennedy to Ford) before representing New York in the Senate, where he worked (and tangled) with another four presidents, from Carter to Clinton. But his relationship with Richard Nixon, in the White House and as ambassador to India, was the most anguished of his long career. Moynihan’s private letters to Nixon and his sta≠, many of them made public here for the first time, are one of the richest literary legacies of one of the nastiest eras of modern American history.

In Moynihan’s White House tenure, the Nixon team was trying to manage the spectacular, incendiary birth of the political universe we still live in today: war protests, racial violence, environmental consciousness, feminist anger, generational conflict, and divisions between liberals and the white working class. The letters show how Moynihan sometimes tried to appeal to Nixon’s better impulses and transcend the nation’s divisions, but how on other occasions he would mount the ramparts with Nixon and his sta≠ and reinforce their resentment of liberal elitists, pampered student protesters, and black militants. The letters published here show Moynihan as consummate diplomat, never two-faced but always conscious of his audience. And the letters, while written for the president, his aides, and Moynihan’s friends, also seem, with their Founding Father eloquence, to be written for history

Moynihan was dubious about Vietnam, and he urged the president not to make Johnson’s war into Nixon’s war. As a New Frontier and Great Society liberal, and the most prominent Democrat in a Republican White House, he thought (naïvely, his friends believed) he could help Nixon find a new vital center in American politics. It was a risky role to play, parts of which Moynihan came to regret, never more, as the last letter shows, than when Watergate raged.

Today, as President Obama confronts a similarly divided nation, Moynihan’s efforts stand as remarkably relevant and evocative. He could draw lines in the sand, but more often he tried to find middle ground, believing in the face of overwhelming evidence that bi-partisanship was possible. As these letters show, it could be a complicated endeavor, and a lonely one. Reasonable people, who see the world in three dimensions, are not guaranteed victory— possibly closer to the opposite. But Moynihan, with his hopes for the Republic, would no doubt have advised the current president that the difficulty of this work was precisely why he had to continue to do it.

January 3, 1969

To: The President Elect

Before the storm breaks, as it were, on the 20th, I would like to send in a few extended comments on some of the longer-range issues that face you, but will tend, I should imagine, to get lost in the daily succession of crises …

It has fallen to you to assume the governance of a deeply divided country. And to do so with a divided government. … A divided nation makes terrible demands on the president. It would seem important to try to anticipate some of them, at least, and to ponder whether there is not some common element in each that might give a measure of coherence and unity to the president’s own responses and, by a process of diffusion, to provide a guide for the administration as a whole.

I believe there is such a common element. In one form or another all of the major domestic problems facing you derive from the erosion of the authority of the institutions of American society. This is a mysterious process of which the most that can be said is that once it starts it tends not to stop.

… All we know is that the sense of institutions being legitimate—especially the institutions of government—is the glue that holds societies together. When it weakens, things come unstuck.

… Moreover we retain a tradition of revolutionary rhetoric that gives an advantage to those who challenge authority rather than those who uphold it.

… Yet it remains the case that relationships based on authority are consensual ones: That is to say they are based on common agreement to behave in certain ways. It is said that freedom lives in the interstices of authority: When the structure collapses, freedom disappears, and society is governed by relationships based on power.

Increasing numbers of Americans seem of late to have sensed this, and to have become actively concerned about the drift of events. Your election was, in a sense, the first major consequence of that mounting concern. Your administration represents the first significant opportunity to change the direction in which events move.

Your task, then, is clear: to restore the authority of American institutions.

Not, certainly, under that name, but with a clear sense that what is at issue is the continued acceptance by the great mass of the people of the legitimacy and efficacy of the present arrangements of American society, and of our processes for changing those arrangements.

… What has been pulling us apart? One wishes one knew. Yet there are a number of near and long-term developments that can be discerned and surely contribute significantly to what is going on.

Of the near-term events, the two most conspicuous are the Negro revolution and the war in Vietnam. Although seemingly unrelated, they have much in common as to origins, and even more as to the process by which they have brought on mounting levels of disunity. … In a word, those in power have allowed domestic dislocations that accompany successful social change to be interpreted as irrefutable evidence that the society refuses to change; they have permitted foreign-policy failures arising from mistaken judgments to be taken as incontrovertible proof that the society has gone mad as well. … The essence of the Negro problem in America at this time is that despite great national commitments, and great progress, a large mass of the black population remains poor, disorganized, and discriminated against.

These facts are increasingly interpreted as proof that the national commitment is flawed, if not indeed fraudulent, that the society is irredeemably “racist,” etc. … Moreover, increasingly that argument is directed not to particulars, but to fundamental questions as to the legitimacy of American society.

Vietnam has been a domestic disaster of the same proportion, and for much the same reason. … At the risk of seeming cynical, I would argue that the war in Vietnam has become a disastrous mistake because we have lost it. …

There is a longer-term development contributing to the present chaos which bears mentioning. Since about 1840, the cultural elite in America have pretty generally rejected the values and activities of the larger society. It has been said of America that the culture will not approve that which the polity strives to provide. For a brief period, associated with the Depression, World War II, and the Cold War, there was something of a truce in this protracted struggle.

That, I fear, is now over. The leading cultural figures are going—have gone—into opposition once again. This time they take with them a vastly more numerous following of educated, middle-class persons, especially young ones, who share their feelings and who do not need the “straight” world. It is their pleasure to cause trouble, to be against. And they are hell bent for a good time.

President Johnson took all this personally, but I have the impression that you will make no such mistake! …

May 17, 1969

For the President

I think you are entirely right to have been disturbed by Pete Hamill’s article: “The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class” [published in this magazine]. To be frank, I would have sent it to you myself, save that it seemed to me this is just what you were talking about during the campaign. “The Forgotten Americans.”

A new voice is being heard in America today. It is a voice that has been silent too long. It is a voice of people who have not taken to the streets before, who have not indulged in violence, who have not broken the law.

These forgotten Americans finally have become angry. They have not really found a voice in American politics, but they are indeed angry. And have reason to be. You ask, “What is our answer.” To which I suppose my first reaction would be to ask, “What is their question?” …

What is the question? It is this: How is the great mass of white working people to regain a sense of positive advantage from the operation of American government, and retain a steady loyalty to the processes of American society, at a time when those above and below them in the social hierarchy seem simultaneously to be robbing the system blind and contemptuously dismissing all its rules. …

August 19, 1969

Memorandum for the President

Autumn now approaches, and with it—such being the singular capacity of American life to compress the social change of generations into demi-decades—the season of student unrest, disorder, and turmoil … beyond the simple issue of campus violence—simple in the sense that almost everyone will agree that students should not club the dean, but neither should they be prevented by bayonets from doing so—the far more complex question of the relationship of the American polity to the newest generation of middle-class youth awaits you. You because, as president, you are the embodiment of that polity. It is, in a sense, entrusted to the president that he be concerned with these profound matters of continuity and change. You also because so long as the Vietnam War continues student protest constitutes an immediate and direct threat to the day-to-day effectiveness of the national government, quite apart from any long range concerns.

… At the great risk of using a term of clinical psychiatry to describe a crisis in the culture, I would offer the thought that American society is becoming more and more schizophrenic. Two opposite and increasingly equal tendencies, often as not united in individuals, are splitting the nation. Norman Podhoretz, editor of Commentary, cites as illustration the fact that just about the two leading box-office attractions of 1968 were The Graduate and The Green Berets. This is, in ways, a continuance of the old “pale face red skin” dichotomy of American culture, but it has now reached massive proportions.

To a degree that no one could have anticipated even three or four years ago, the educated elite of the American middle classes have come to detest their society, and their detestation is rapidly diffusing to youth in general. The effects of this profound movement of opinion will be with us for generations. It will, for example, drastically limit the role that the United States can play in world affairs—in contrast with the past three decades or so during which the national government has been really extraordinarily free to do what it thought best. There will be indirect effects. The movement of the American youth away from business will almost surely affect business. If it continues, I would imagine it almost certain, for example, that by the year 2000 the Japanese will have a higher per capita income than do the Americans. In one way or another, we are involved in a change of cultural dimensions that will be pervasive in its consequences …

August 20, 1969

Memorandum for the President

Predicting the future is never an especially productive enterprise in politics. But when seemingly unmistakable signs of an emergent political force begin to appear on every hand, and yet are somehow ignored, it is worth the slight risk to one’s reputation to try to point them out. … I do not wish to burden you with details. The essential fact is that we have educated women for equality in America, but have not really given it to them. Not at all. Inequality is so great that the dominant group either doesn’t notice it, or assumes the dominated group likes it that way. (An old story!) Did you happen to note, for example, Erik Erikson’s comment that there were no women present at our meeting of educators. He might well have commented on the general absence of women from higher education in America. It is considered too important for them. They teach kindergarten. (Which, I might add, may indeed be too important for them!) I would bet there are proportionately more women in the Marine Corps than on most university faculties. Thus higher education subtly perpetuates the notion that women have equal rights, but not really equal potentialities, etc.

I am no great fancier of India or Ceylon. But consider the apparent ease with which those countries have accepted female heads of state. Consider how odd the idea of a lady president would be to us. I repeat: Male dominance is so deeply a part of American life that males don’t even notice it.

I would suggest you could take advantage of this. In your appointments (as you have begun to do), but perhaps especially in your pronouncements. This is a subject ripe for creative political leadership and initiative.

September 17, 1969

For John Ehrlichman

As with so many of the more interesting environmental questions, we really don’t have very satisfactory measurements of the carbon-dioxide problem. On the other hand, this very clearly is a problem, and, perhaps most particularly, is one that can seize the imagination of persons normally indifferent to projects of apocalyptic change.

The process is a simple one. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has the effect of a pane of glass in a greenhouse. The CO2 content is normally in a stable cycle, but recently man has begun to introduce instability through the burning of fossil fuels. At the turn of the century, several persons raised the question whether this would change the temperature of the atmosphere. Over the years, the hypothesis has been refined, and more evidence has come along to support it. It is now pretty clearly agreed that the CO2 content will rise 25 percent by 2000. This could increase the average temperature near the Earth’s surface by 7 degrees Fahrenheit. This in turn could raise the level of the sea by ten feet. Good-bye, New York. Good-bye, Washington, for that matter. We have no data on Seattle.

It is entirely possible that there will be countervailing effects. For example, an increase of dust in the atmosphere would tend to lower temperatures, and might offset the CO2 effect. Similarly, it is possible to conceive fairly mammoth man-made efforts to countervail the CO2 rise (e.g., stop burning fossil fuels). In any event, I would think this is a subject that the administration ought to get involved with …

March 12, 1970

Memorandum for Mr. H. R. Haldeman

For about a year now, I have been keeping a file and thinking to send you a memo on the subject of terrorism. The time has come. …

The level of political violence has been escalating steadily for the past two to three months. In the last week, bombs have been exploding up and down the Eastern Seaboard. …

Political violence is not new to the nation. We are alone among the “stable” democracies in the number of presidents we have had assassinated. Our early labor history was singularly violent. And into our time, whites have ruled over blacks in the South with the threat and the use of violence. (Think what you will of the Black Panthers. They still haven’t blown up any children in church.)

But I do believe the present situation is different. What we are facing is the onset of nihilism in the United States …

The “culture” is more in opposition than at any time in history.

July 24, 1970Personal & Confidential Memorandum for

John D. Ehrlichman

H. R. Haldeman

Over last weekend I found myself thinking about our brief discussion of the difficulty the administration seems to have in linking up with competent, respected conservative thinkers. I had not the time, as they say, to write a brief memorandum, and so I send you this, as I felt both of you were interested in the subject. You should be: The presidency is at stake.

… In the best universities, the best men are increasingly appalled by the authoritarian tendencies of the left. The inadequacies of traditional liberalism are equally unmistakable, while, not least important, the credulity, even the vulgarity of the supposed intellectual and social elite of the country has led increasing numbers of men and women of no especial political persuasion to realize that something is wrong somewhere.

These persons are the president’s natural allies. They can be of help to him, and to the country. But I do not see them brought into our counsels. Mostly, if I am right, because of a sense of inadequacy hereabouts. Better stick with Kate Smith and the Silent Majority. They aren’t very smart, but then neither are we.

As I say, I feel this is wrong, and that something of importance is at issue. Moral authority and political power. Pragmatism is a noble political tradition. It is vulnerable, however, to a form of oversight which can be calamitous. The pragmatic mind in politics tends to underestimate, even to be unaware of, the importance of moral authority. … What is to be done? This first thing to be clear is that our own power to influence events is limited. America has developed, in Lionel Trilling’s phrase, “an adversary culture.” I wrote of this in a memorandum to the president on January 3, 1969 …

The “culture” is more in opposition now than perhaps at any time in history. The president will have to live with it permanently, I should think. We can’t change this. … But in the meantime, it is within our power to make matters worse. We have shown that we can do so. I would argue that in such circumstances the first [rule] of patriotism is the willingness not to worsen things, even when the provocation is outrageous, even when there may appear to be a short-term advantage to be gained. This is not just the measure of patriotism, it is the measure of prudence as well. I would hope the events of the past winter will have demonstrated how extraordinarily weak we are. When attacked, nobody defends us. No one in the Congress, certainly no “liberal” Republican helps us. No one writes articles for us, much less books, or plays, or folk songs. …

I have spent eighteen months in this building pouring gin into various newspapermen, and I can attest that it is possible to get them to consider the possibility that what I say might be true. But I can’t do it anymore. It needs to be done by real Republicans.

… I have troubled you with all this because I am conscious that my time hereabouts is fast running out. I feel deeply about this matter. I don’t yet feel others feel deeply enough. By which I mean, I feel that much of the trouble we are now somewhat unceremoniously trying to dig our way out of could have been averted had we kept in mind the precariousness of the president’s—any president’s—position in America at this moment. I restate it now in the thought that if anything is to be done there would still be time for me to be of some possible help.

[A letter to his friend Nathan Glazer]

May 25, 1973

Dear Nat:

… I have been thinking of little but Watergate, and thinking of just the question you put: “… Is Watergate a difference in the quantity of political skulduggery, promoted into the disaster it is by a special relation to press or media, or a difference in real quality, which reflects some basic moral and political failing both of Nixon and those of us who saw him in the mainstream of American politics, rather than as some cunning aberration?” You say you wouldn’t know how to answer that question if anyone asked, and neither would I. Thirty years of reading and forty of going to Catholic churches leave me with almost no preparation even for putting the question; much less answering it. Have I been a fool or a whore or both? Or perhaps something quite different; something perhaps to be forgiven.

… I had looked, with others, for some relaxation after the campaign. None came, but then [Charles] Colson left, and this was cause for something near rejoicing among those in the White House who were and are decent, honorable, competent public men.

I think these men knew little or nothing of Watergate. And yet what cringing animals this makes of us all. “I Knew Nothing.” It makes us not only animals, but liars. Not worse, different. Of course they knew. There is a sense in which we all “knew.” … I wanted no part of that administration, yet I did not break with it. Next, I voted for it—privately, to be sure, but I did vote for it. Finally, I returned to it.

What do you call such a person? A Moynihan, I suppose. A term suggestive of moral and political failing. Yet what is it? Two things, somewhat opposed. First, the moral failing of being more concerned with deviations from one’s own general position than with positions flatly and openly opposed. This is the classic condition of the true believer, and one of which we have been more than a little contemptuous. And yet has it not been our condition also? Have we made a passion of pragmatism? Whatever the case, we spent much of the 1960s appalled at the decline of intellectual and even moral standards on the liberal/left. We saw this as a phenomenon of ideology, when in fact it was increasingly a function of what American government was becoming. When a conservative government came in and seemed sensitive to the fooleries of its predecessors, we were too grateful by half, and altogether too willing to supply arguments. We were willing to be used. … All right. But why did we not have the political sense to see that sooner or later this would happen? We know the world. We surely saw that the men of the Nixon administration who, in Elliot Richardson’s words to the Senate Judiciary Committee, “betrayed” us by their “shoddy standard of morals” are not “normal” men. They are so straight they are deviant. Ehrlichman, for one, always seemed to me a clinical case. Buttoned up to the point of bursting. And if we could have seen this coming, we could have taken the great prudential precaution of being out of the way when it hit. I would not worry myself about your own position. … But still, there is a general truth in your statement that “the people we have been fighting all along now seem to win.” … I feel I myself had a lot to do with this.

Excerpted from Daniel Patrick Moynihan: A Portrait in Letters of an American Visionary, edited by Steven R. Weisman (to be published in October 2010 by Public Affairs, a division of Perseus Books).