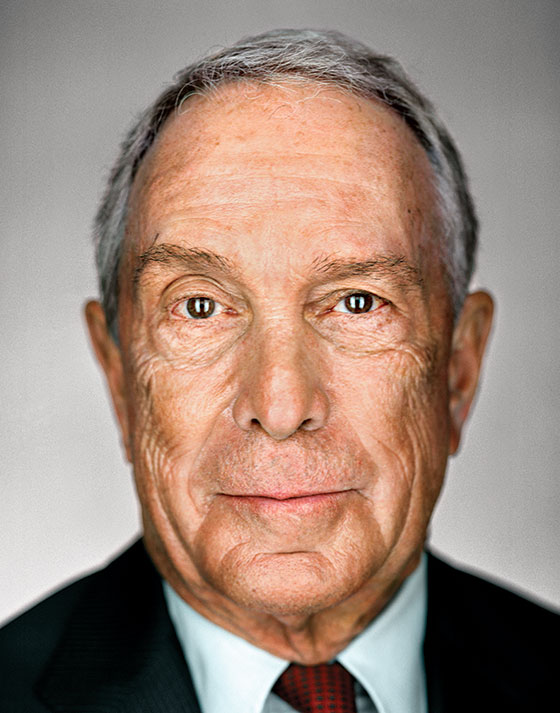

It was clear from the very beginning that Michael Bloomberg was taking us to a different political universe. A novice candidate who had barely won office with 50.7 percent of the vote, he had spent the first months of 2002 in City Hall closing a nearly $5 billion budget deficit. That was why he’d been elected, to make tough managerial choices as a recession accelerated and the city tried to rebound from a devastating terrorist attack. Yet the following year’s budget crisis was sure to be worse—a property-tax increase appeared inevitable, maybe one as high as 25 percent. New York’s middle class and poor were already taking a beating and, in his determination to move the city past the tragedy of 9/11, Bloomberg had started to antagonize victims’ families. So with his honeymoon beginning to fade, the multibillionaire mayor was choosing this moment to insist that one of his most urgent priorities was … banning smoking in restaurants and bars?

“It was totally voluntary. You don’t need to take on that fight, and it’s politically harmful,” says Ed Skyler, Bloomberg’s first-term press secretary. “The property tax and the smoking ban at the same time, it made him seem sort of anti–middle class, anti–working class. Politically, it was a bad combination.”

But Michael Bloomberg didn’t care. Smoking killed. And besides, Bloomberg had lured his public-health commissioner, Dr. Thomas Frieden, from an important post battling tuberculosis in India by promising to eradicate smoking in the city. The mayor was going to stick to that promise, and the sooner he followed through, the more lives he would save. But Frieden, who had worked in city government before, was still somewhat skeptical that Bloomberg would follow through. “So I said, ‘But Mr. Mayor, I do want to warn you that this is going to be really controversial; they are going to be attacking you, it’s going to be very unpleasant,’’ Frieden says. “And he interrupted me and said, ‘Do you know what the first rule of sales is?’ And I said, ‘No, no I don’t.’ And he says, ‘The first rule of sales is: Once you’ve made the sale, leave.’ And then he laughed.”

Now it was Bloomberg who needed to make the sale. He’d defied the laws of political gravity once already, winning control of the city’s public schools. But smoking was different. Bloomberg needed a law to be passed by the City Council.

Bloomberg brandished statistics about increasing life expectancy, and his aides testified in public hearings—all the standard old-politics moves. But he had spent $74 million to get elected. Now like-minded outside groups that had already been or soon would be recipients of Bloomberg’s charitable millions, like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, sprang into action. Radio ads from the city’s Health Department soon appeared. Petition drives in support of the ban were launched. A poll showed broad support for the idea.

By December, New York had the toughest anti-smoking law of any big city—something few in the city had wanted, until Michael Bloomberg decided to give it to them.

The smoking ban was, like many of the mayor’s initiatives, beyond politics. His wealth, and the habits of mind that accompanied it, allowed him to be his own constituency. Under Michael Bloomberg, the old politics of tribal shouting and horse-trading didn’t disappear completely—but the mayor’s way of playing raw politics was handing the state’s Independence Party more than $1 million when he needed a ballot line, for instance. Bloomberg sold himself as a postpartisan technocrat, yet the hallmarks of his governing style turned out to be simpler and more personal: By temperament and habit and bank account, he could choose what he wanted to listen to. And what he didn’t want to hear was noise. Most often, the old clamor of New York’s traditional political machinery was a disturbance heard at a distance, replaced by an obsession with data and money and pure Bloombergian idiosyncrasy.

There was, often, little balancing of interests or conciliation of stakeholders, the sorts of things that even Rudy Giuliani had to indulge in from time to time. Instead, there was an emphasis on the long-term, and rationality—“the merits,” as defined by the mayor. His core independence from the old political forces enabled Bloomberg to undertake acts of political bravery that benefited millions: He was autocratic for the people. Yet that independence could swell into imperiousness, like 2008’s term-limits extension, a high-handedness that is haunting the current campaign to succeed him and is likely to leave its own lasting mark on New York’s politics.

The city, back in 2001, thought it was electing a new mayor. Bloomberg, for two years of his reign its richest citizen, believed the city had installed him as its new boss. He would make New York a magnet for the 21st-century economy, a winner in the global competition among cities, and save us from ourselves, if we would only let him. The specific admixture of wealth and arrogance and brains and political innocence that bent the city’s valences to his ends will be impossible to re-create. No matter who wins in November, Michael Bloomberg’s greatest feat—the way he upended the city’s entire political system—may also turn out to be his most ephemeral.

As Bloomberg leaves office, he can accurately be labeled a visionary. He pursued ambitious, difficult objectives, many of which were unpopular and had short-term political consequences. He pushed New York ahead of the curve on issues, drastically reducing crime and the carbon footprint, making the city a canvas for giant artworks, paying kids for good grades. Bloomberg enlarged the notion of what a city can and should do—partly because he’s a citizen of the world, inspecting commuter trains in Hong Kong and discussing greenhouse gases in Rio, partly because innovators and potentates seek him out.

What’s remarkable, though, is how little of what will define his legacy originated with Bloomberg. His values were well-defined—socially liberal, fiscally pro-business—and his priorities clear: job creation, education, public health. But unlike most traditional politicians, Bloomberg was determined to hire strong deputies and didn’t much care who got the credit for success.

In crucial ways, Bloomberg was a man from nowhere. “We thought we could run an honorable campaign,” says Kevin Sheekey, who directed the improbably successful 2001 effort and Bloomberg’s 2008 presidential-campaign flirtation. “We didn’t think for a minute about how much we could achieve in terms of government. You knew Mike had incredible intelligence—great macroeconomic thinking. But he’s not a guy who had studied these issues. He’s a guy that said, ‘Jeez, I gotta figure out how to spend my time. I think I can make a difference.’ ”

Beyond that, though, the Bloomberg agenda was mostly a blank slate. He’s a believer in science and progress through experiment, so the city became a giant laboratory. The most significant particulars were filled in by four top lieutenants. Bloomberg’s political independence allowed him to choose aides from outside normal political channels—he didn’t owe favors or jobs. So the mayor picked people who were, in essential ways, reflections of him: They’d already made their reputations and, in some cases, fortunes. They didn’t need the jobs Bloomberg hired them to do.

In the winter of 2001, before he was officially a candidate, Bloomberg walked the dilapidated Williamsburg shore with Amanda Burden as his tour guide. She noticed him studying some notes. “I asked him, ‘What are you looking at?’ ” she remembers. “They were Spanish-English flash cards. And that’s when I realized he was running.” At the time, Burden was a member of the City Planning Commission, reappointed by Mark Green, who was about to run for mayor as a Democrat. But Burden had other qualities that made her attractive to Bloomberg. She was an uptown social X-ray with substance, an heiress to an oil fortune who’d become a rabid student of urban planning. Also, helpfully, Burden was a close friend of Patti Harris, one of Bloomberg’s most trusted aides at his company and now at City Hall. “He was voracious for information,” Burden says. “He just wanted to get ideas. He wanted to know what I thought were important things for the next mayor to do. So I’d been looking at the Brooklyn waterfront. It had become completely nonproductive, and it was cutting off this burgeoning community of young people and people who had been there for a long time. There were two miles of chain-link fence on the water’s edge, so I took him there and around Bed-Stuy and Greenpoint. But Williamsburg really stuck with him.”

Bloomberg installed Burden as director of city planning. She’s stayed the entire run, and her imprint can be felt from the Bronx to Staten Island. Bloomberg initially dismissed the notion of repurposing a rotting elevated section of railroad track—but Burden’s passion and her legwork in transferring neighborhood development rights won over the mayor and turned the High Line into the catalyst for a Chelsea boom.

Nearly 40 percent of the city’s landmass will have been rezoned by the end of Bloomberg’s reign—probably his most significant legacy, especially considering the new construction the zoning changes enabled. The particulars vary by neighborhood, but the driving idea has been unvarying: Development equals economic growth. (The corollary proposition: Wealth provides tax revenue.) “He wanted economic development, jobs, housing, in all boroughs,” Burden says. “Maybe because of seeing Williamsburg and the waterfront, he’s wanted to recapture underutilized industrial areas. And he’s seen the water as the tissue connecting the boroughs. People view the city as a waterfront city now, and he made that happen.” There have been setbacks, unfulfilled promises: Condo towers now line Kent Avenue, but Bushwick Inlet Park has been severely delayed. Burden admits to frustration over the inability to acquire the remaining land. “It’s all about money,” she says. “We spent an enormous amount of money purchasing the properties. Listen, part of the esplanade has happened. It looks very good at North Side. I’m very emotionally attached to Greenpoint and Williamsburg, and we don’t have money in this agency. When we propose projects like this, the only thing we can trade on is people trusting us. So to have that trust eroded at all—it’s painful every time I go there.”

It never stopped being surreal, the contrast of the high-production-value Bloomberg show—full of slick PowerPoint presentations and glossy highlight-reel videos—with the sweaty, scruffy hustle of everyday New York politics. Sometimes the effect was comic, as when Bloomberg would don a bubblegum-pink sweater to march in the Pulaski Day parade. More often the culture clash was jarring: The multibillion-dollar-man piloting his own sleek $4 million helicopter into Albany, the capital not just of the state but of the shiny-suited, self-interested old politics that Bloomberg disdained.

The mayor’s first deputy mayor of economic development was Dan Doctoroff, who’d made millions as an investment banker in the eighties and nineties, then became a proselytizer for bringing the 2012 Olympics to New York, which is how he met Bloomberg. Doctoroff’s impact on the city outstrips even Burden’s, and much of his success flowed from a stinging defeat. The Bloomberg administration got more from the State Legislature than is commonly recognized, but Albany denied Bloomberg congestion pricing and a $2.2 billion West Side stadium. The mayor’s bitter analysis is that his proposal for the stadium, a centerpiece of the failed bid for the Olympics, was thwarted by Sheldon Silver, the State Assembly speaker, who killed the idea to protect his lower-Manhattan district from competition, and Jim Dolan, who didn’t want a new entertainment mecca competing with Madison Square Garden. But in a warped way, the death of the stadium was an assertion of democracy by Albany.

To Doctoroff, now president and CEO of Bloomberg LP, the stadium debacle demonstrated Bloomberg’s best qualities, his loyalty to staff and his imperviousness to political pressure. “We were bidding for the Olympics, and Cablevision was so aggressive in fighting it, at a time when he was gearing up to run for reelection in 2005,” Doctoroff says. “I went to him and said, ‘Look, if the cost of pursuing the Olympics bid is that you are not going to get reelected, then it’s not worth it.’ And Mike looked at me sort of with this anger in his eyes that I’d rarely experienced and said, ‘I don’t ever want to hear you say that again. We got into this together, it was the right thing to do, we’re gonna see it to the end.’ About a month later, the stadium went down to defeat. The only thing he said to me was, ‘Okay, so what’s Plan B?’ ”

Part of the answer is Hudson Yards, which is shaping up to be the quintessential expression of Bloombergism: big, expensive, highly manicured, with a fine-arts sheen and serious insider connections—Doctoroff is chairman of the board of the mini-city’s Culture Shed arts organization. The development is another marker in the spiraling cost of living here. The Democrats running to succeed Bloomberg have made affordability and income inequality central campaign issues, but the architects of Bloomberg’s development strategy don’t believe there was ever any choice.

“I think the notion of a split is simplistic and unfair,” Doctoroff says. “Six percent of the population of the city is now living in housing that they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to afford in basically every neighborhood in the city. That’s not to say gentrification doesn’t have negative consequences. It’s the ability to generate those additional revenues from growth that makes the good things possible; that’s a virtuous cycle. I don’t see anyone running for mayor who basically thinks about that, about generating marginal revenue—instead, it’s all about what we have to do in order to deal with the compassion problem.”

This is the heart of Bloomberg’s operating philosophy: something between noblesse oblige and trickle-down, coupled with a genuine desire to see hard work rewarded. And it’s what’s made the mayor’s reign brilliant and exasperating. Bloomberg won in 2001 because he seemed the right man for the post-9/11 moment: a self-made billionaire from the financial sector who could attract jobs and competently manage city government as New York grieved and fought back. His skills, connections, and experience were perfectly suited to rebuilding the city’s economy.

“Even before he was sworn in as mayor, Mike called the CEOs of companies and said, ‘I will guarantee you that we will do everything possible to try and make sure you are free from another terrorist attack,’ ” says Kathy Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York City, the big-business group that’s been an important Bloomberg backer. “And they made huge decisions on their companies and their companies’ lives based on that phone call. They would have never believed that from a politician, but they knew he was going to make decisions on the same logical basis that they do. He is the only person—the only mayor—with the credibility to do that.”

As the decade unspooled, though—a time of headlong technological change and wild financial swings—Bloomberg also became the almost too-perfect symbol of his own city. He was an up-from-the-middle-class product of education and hard work who struck it rich selling a digital breakthrough in the packaging of financial information to Wall Street. As tech reshaped society, and the financial industry assumed an outsize role in New York’s life, and the city’s income extremes grew wider apart, New York’s mayor happened to be a man who both cared about improving the city services most vital to the 99 percent—schools, parks, transportation—and was the very embodiment of the one percent. Shrinking crime to historic lows spared the innocent, but a safer city also attracted commerce; better schools produced more valuable potential employees, drawing still more new businesses. The means to those two ends were less important. Which is why two of the realms that touch millions of day-to-day New York lives have proved the messiest for Bloomberg. A traditional pol, rising from community board to citywide office, might be beholden to special interests—but also might be responsive to the grassroots. Because of who he is and what he believes, Bloomberg approached issues as an engineer bent on fixing systems, not as an elected official sensitive to the lives of actual people.

From his first campaign, Bloomberg asked to be judged on whether he improved the city’s schools. And the battle over how the city educates its young people is an object lesson in Bloombergism, in all its strengths and intrinsic flaws. Bloomberg finally won mayoral control because he was different from his predecessors in one pivotal aspect: He was on no one’s side. The State Legislature could rid itself of a headache without rewarding or punishing any of the many traditional actors in the education drama. Bloomberg was a free agent, arriving with no enemies and no real constituency, and it provided him, at the outset, with a rare reservoir of political trust.

Now that he was responsible for more than 1 million kids, however, Bloomberg needed to figure out what to do with them. As much as he believes in data, as much as he comes across as cold-bloodedly analytical, Bloomberg has often relied on instinct when selecting lieutenants. “We needed an education guy,” Sheekey recalls, “and Mike said, ‘Well, Joel Klein is a really smart guy. Why don’t we try Joel?’ ” In Klein, Bloomberg got a brilliant legal mind and a tenacious fighter—with perhaps more of the second quality than Bloomberg had bargained for. Relations with the teachers union started out fairly cordial, and the mayor’s awarding of substantial pay raises in advance of his 2005 reelection campaign certainly helped. But things deteriorated in the mayor’s second term as Klein’s top-down, test-heavy reforms aggravated parents and the UFT’s leadership changed from Randi Weingarten to the more combative Michael Mulgrew.

“Let me cop to this—I’m sure there are things I could have done better,” Klein says. “I could have reached out or whatever. But make no mistake about it, until we showed up, the union was the thousand-pound gorilla. Then the second group were the bureaucrats. In order to effectuate change, you have to go after those very powerful groups. This big change could not be done without a lot of noise and a lot of pushback.” And for most of Klein’s tenure, he knew Bloomberg had his back. “You can agree with Mike or disagree with Mike, but I do think he really cares deeply about policy and fights for things he believes in. He’s not the man in politics who holds his finger to the wind. He’s pretty much a guy who believed deeply that the system here was broken and that it was critical to the future of the city to fix it. He wanted somebody who wasn’t a careerist, somebody outside the system who has not grown up acculturated to it, who was more likely to have a chance to change it.”

Sheekey rues the errors that hurt those chances. “Two things we got wrong were how we define charters and how we define closing schools,” he says. “Unfortunately, a lot of charters get described as not public schools, which of course they are. That was the first mistake. And the second mistake was ‘closing schools,’ because we’ve never closed a school. Ever. We remove the principals and the teachers and replace them with new structures with the same children in the same buildings. That’s obviously not closure. But we screwed up the language, because communication wasn’t the concern; doing the right thing was always the concern. Communication almost seemed like capitulation.” Bloomberg’s education-reform goals—spreading quality education across the city, especially to poor neighborhoods—have been progressive and egalitarian, even when the methods—a mania for testing, the shaming of teachers—have been needlessly authoritarian.

The mayor’s instinct for hiring creative thinkers and outsiders to run major agencies has usually served him well—from housing boss Shaun Donovan to Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan and development chiefs Seth Pinsky and Bob Steel. But when Bloomberg replaced Klein, the mayor’s hubris undermined his own cause—choosing the disastrously overmatched publishing executive Cathie Black as schools chancellor shredded most of the goodwill he had left with parents. The fight over the results of education reform will rage for at least the next twelve years. There are more good schools than there were in 2002; graduation rates are up. The mayor has brought energy and money to neighborhoods like Brownsville and Mott Haven where schools had languished for decades. Yet there’s also been a continuous, destructive churn, and many of the kids who are toughest to educate are still stuck in dysfunctional schools. And cynicism about the letter grades assigned to schools is so deep as to make the innovation practically meaningless. The real impact of Bloomberg’s school reform, however, will play out as the generation of teachers hired in the past twelve years becomes the core of the classroom staff. It’s a group raised on constant numerical evaluations and iPads instead of lifetime tenure and chalkboards. All they’ve known is the Bloomberg way—and they will determine how much of the change is permanent.

Bloomberg’s choice for police commissioner was much more of a known quantity. Ray Kelly, after years of rising through the NYPD ranks, had served briefly in the job under David Dinkins. The mayor certainly wanted the city to become safer, as a condition for its economic success as much as anything else. But the operational details of NYPD policy weren’t a fixation at the outset of his administration.

Now, though, Bloomberg is vehemently defending his Police Department’s tactics, and his stubbornness is eroding what should be a prime part of his legacy, the plummeting homicide rate. The mayor’s June statement that “I think we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little” wasn’t merely tin-eared; Judge Shira Scheindlin cited it to support her August decision declaring the NYPD’s implementation of stop-and-frisk not merely unconstitutional but racially discriminatory. “For Mike Bloomberg, it’s like, ‘Well of course what I’m saying is true,’ ” a mayoral ally says, wincing. “But for you and I, the hair on the backs of our necks is standing up. When it comes to thinking what we need to do, how do you weigh these big things—he takes his own logic and builds these incredible systems that lead to incredible results. But when it comes to the one-on-one, thinking about people—he’s probably one of the worst mayors.”

One great Bloomberg paradox is that even as the mayor developed a deeper feeling and appreciation for New Yorkers as individuals—much of it through tragedy, such as the hours he spent in hospital emergency rooms comforting the widows of cops and firefighters injured or killed in the line of duty—he increasingly treated the citizenry as data. So the New York City Marathon, a week after Hurricane Sandy, needed to be run to bring in more tourism revenue. During his first campaign, the mayor made an offhand remark suggesting that sanitation workers had the most dangerous city jobs. This, naturally, infuriated cops and firefighters. Bloomberg not only didn’t backtrack or amend his comments—a dozen years later, he was telling aides how the most recent statistics proved his point all over again.

It isn’t mere tone deafness with Bloomberg; it is a system of belief. “People think Mike’s a dick,” a top adviser says. “And he revels in it.” That attitude freed him to do great things for the city. But Bloomberg’s allergy to political and public friendship could also be the flaw that keeps his legacy from being even greater.

“I think Mike Bloomberg is an incredibly well-meaning person,” says a New York Democrat who has both clashed and cooperated with the mayor. “I think he wants to help people and make the world a better place—and there are a helluva lot of billionaires who don’t. But I don’t think he has the emotive ability to understand what other people are thinking, or has any desire to. It’s funny to me, because he was supposed to be this great salesman. He’s a terrible salesman. He doesn’t get other people.”

It’s a truism that Bloomberg’s money enabled his election and allowed him to float free of the warring interest groups that have traditionally dominated New York politics—but the effect of his wealth has been more far-reaching than has often been apparent. Less easy to chart than his donations to candidates, and more important, have been the funds he’s created to supplement city agencies with private dollars, everywhere from the school system to Governors Island. In 2010, Bloomberg raised millions of dollars for Education Reform Now, the lobbying group that pushed successfully to raise the state cap on charter schools. A new quasi-governmental technology-development project, funded mostly by private donations, is contracting for digital experts outside the civil-service salary structure who can untangle the city’s conflicting computer systems.

“Mike’s personal money has had a major impact on just about everything he’s done in city government,” Kathy Wylde says. “Education? Huge influence. Health? Huge influence. Cultural affairs, social services, and the whole anti-poverty thing. He has leveraged expertise, called in philanthropic chits, created pilot projects, much of it anonymously, put together teams, put together public-relations efforts around them—enormous investments in everything that’s happened.”

Probably the most spectacular political manifestation of those investments was Bloomberg’s campaign to rewrite the city’s term-limits law in 2008 to give himself a chance to run again. It was also a powerful demonstration of how the mayor’s money had sifted into almost every corner of New York’s public life, intimidating some opponents and co-opting others. In his first term, when Bloomberg cut the budgets of cultural institutions to help close a budget gap, he quietly reached into his own pocket to make up some of the difference. He saw it as a smart investment on behalf of the city: Museums and theaters and ballet troupes drew tourists, who spent money in New York’s hotels and restaurants. But over time, as the flow of Bloomberg money to arts and education groups turned into a flood—he channeled nearly $200 million through the Carnegie foundation—it became politically useful, helping smooth the path to four more years.

On a chilly March night, a crowd gathered at Mike Bloomberg’s place. Not Gracie Mansion, which he’s had meticulously renovated but which he has refused to live in, and not his actual home either; that’s a mansion around the corner. The party was on the gleaming second floor of Bloomberg’s foundation offices, inside an elegant Stanford White–designed limestone-and-yellow-brick townhouse that the mayor bought for $45 million. The interior shines with glass walls and original artwork and, this night, about 100 members of the ruling class.

There was Caroline Kennedy, whom he tried to make a U.S. senator. And Tim Geithner. Barry Diller. Next to Martha Stewart. Next to Nate Silver, who was spilling his beer. Here’s the party’s co-host, Arianna Huffington. Gayle King. Sean Hughes, the Facebook multimillionaire turned New Republic owner. Charlie Rose. George Packer and Dexter Filkins, chatting about war zones. Andrew Ross Sorkin of the Times and Tim Armstrong of AOL. Christine Quinn, of course. Chuck Schumer. And George Lucas. George Lucas?!

They had assembled for a book party, celebrating Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. Even though the Facebook COO was the star of the show, that evening, as with every big event in his final year as mayor, felt as much like a valedictory for Bloomberg as anything else. Bloomberg, never wistful, was enjoying himself but using every remaining minute of his mayoral time to argue his case. “Arthur!” he shouted mischievously, spotting New York Times owner Arthur Sulzberger Jr. “Your facts are not straight!” Something in that morning’s paper irritated the mayor—maybe the story about a setback in the fight to shrink the size of sugary drinks—and Bloomberg leaned in to give Sulzberger a piece of his mind.

The night’s guest list needed a few more plutocrats to qualify as a crowd of Bloomberg’s peers. But in many other ways this was his crowd, the best connected, the cleverest, the most tough-minded. And in this heady company the applause for Bloomberg was loud, the mood admiring, even affectionate.

Being mayor certainly has not hurt Bloomberg’s net worth: It has soared from $4.5 billion when Bloomberg was first elected to $27 billion today. And his wealth is an uneasy metaphor for the city he’s helped to create. As New York has become safer, its schools better, its air cleaner, the city has attracted more people. The mayor sees it as bottom-line vindication: People voting with their feet, 250,000 more city residents than there were when he took over.

Yet success drives up rents and strains the finances of longtime middle-class residents. The mayor has tried to ameliorate some of the pressure with an affordable-housing program, but the free market keeps outstripping the subsidies. Nearly one third of New York’s renters now spend more than half their monthly income on shelter, according to NYU’s Furman Center. As the proportion of millionaires climbs, so does the share of New Yorkers living at or near the poverty line. “Low-income people are being squeezed into fewer and fewer spots around the city,” says John Mollenkopf, a professor of political science at cuny, who gives Bloomberg’s tenure generally high marks. “Do we have a right as a city to ask that the bounties from our economic success be shared widely and broadly and fairly? I think the mayor would tend to say no, whoever gets, gets, and the market picks out the most talented.”

To Bloomberg, the carping about inequality is just an election-year pose by the candidates trying to succeed him, and economic fairness is best expressed in results: Safer streets, better schools, and more diverse job opportunities make for longer, upwardly mobile lives. Just look at the numbers. He has been a great mayor in many ways. He has also been a thoroughly unique civic creature, one that has never existed before and will not be seen again. Michael Bloomberg leaves behind plenty of bike lanes, skyscrapers, parks, stadiums, and smokeless bars. What won’t last is a New York governed outside the realm of New York politics.