T his isn’t Day One, when Eliot Spitzer is sworn in as governor and everything is supposed to change in Albany. This is day minus-34, and it’s midtown Manhattan, inside the battered former headquarters of an ad agency. And technically, Spitzer is still the state’s attorney general. But he’s charging down a hallway in his transition offices, past leftover ad-company logos that read FRESH IDEAS and FRESH PERSPECTIVE, reading a copy of a just-released report on hospital closings, and shaking up state government from 145 miles away.

He turns into his fourteenth-floor office—the corner office, naturally, overlooking the intersection of Park Avenue and 33rd Street—and sits down to read the 231-page Berger Commission report. In the office next door sits Rich Baum, Spitzer’s chief political aide; at the far end of the hallway is the other bulwark of the administration-in-formation, Paul Francis, the numbers guy, who’s responsible for making sense of the reams of state budgetary data—a fat three-ring binder on his desk is open to a page headed “Gap-Closing Measures.” In between are the offices of David Nocenti, an ace lawyer from Spitzer’s AG staff, and Jim Tallon, Spitzer’s adviser on health-care issues. Each man starts flipping through a copy of the hospitals document, which could be an extremely useful weapon in Spitzer’s looming battle to shrink the state’s wildly expensive health-care system. Thirty minutes later they all hustle into Spitzer’s office to swap analyses. At 2:45, Spitzer issues a public statement underlining the seriousness of the state’s health-care crisis and promising that he’ll soon declare whether he supports the Berger recommendations—even though he’s already made up his mind. Then Spitzer and his team return to working the phones to monitor the reaction of the mighty health-care-workers union.

The guy who’s still in charge of the state? Who has to quickly determine whether to send the report, which would eliminate about twenty hospitals, to the State Legislature, which would then have until December 31 to accept or reject it? George Pataki is in an undisclosed location (it eventually turns out to be Iraq). Only if reporters call Pataki’s office do they get his transcribed thoughts: “At this time we have received the full report and are giving it a thorough review.” Sorry to bother you, Governor.

Yet for all the messes Pataki leaves behind after twelve years in office—a bloated health-care system, brutal property taxes, underfunded city schools, multibillion-dollar structural deficits—at least he’s eager to get out of town. The scariest problem in Albany is the pair of guys who are staying.

As attorney general, Spitzer won his most famous victories without even entering the courtroom. He had the facts behind him, sure, but he turned the use of shame into an art form, with the press as his delivery vehicle. As governor, he’ll need more than a single silver bullet. Spitzer will again shine a spotlight on enemies and hold himself out as moral exemplar, and he’ll argue for the rightness of his policy ideas. Politicians don’t shame as easily as publicly traded corporations, however. So Spitzer will try stroking at first. But if that doesn’t succeed, he’s preparing to use his electoral mandate as a wedge to separate Joe Bruno and Shelly Silver from their usually lockstep followers, and his popularity as a shield against the army of lobbyists.

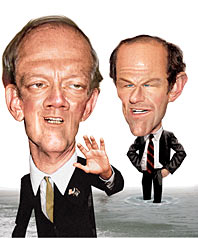

Bruno and Silver were both elected to the State Legislature exactly three decades ago. In 1995, thanks to a Pataki putsch, Bruno became majority leader of the Republican-controlled State Senate; one year earlier, Silver rose to the top of the Democrat-dominated State Assembly. Though they differ in political philosophy and style, Bruno and Silver are blood brothers in self-preservation, using a combination of pork and fear to maintain discipline in their ranks.

Bruno got a jump on the posturing over hospital reform. Two weeks ago, he issued a list of his “priorities for 2007,” and most were predictably conservative. But then came Bruno’s opposition to “gratuitous cuts to health care.”

“We saw that,” a Spitzer aide says, “and said, ‘Wait a minute—isn’t he the Republican?’ ” But the allegiance of Albany’s big two is more to power than to party: Bruno held on to his Senate Republican majority this fall with the help of hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign cash from 1199 SEIU, the influential health-care union. True to form, Silver’s immediate reaction to the hospital-closings report was to argue legalisms and stall, by calling for public hearings. Thirty years in office apparently haven’t given Bruno and Silver enough insight on the situation.

Bruno is 77, with a sheaf of immobile white hair; Silver turns 63 in February, but his droning basso voice makes him seem like a character out of the Old Testament. Spitzer, 47, appears to be perpetually pitched forward into a headwind. He endorsed the Berger Commission report because he agrees with it. But Spitzer’s hospital calculations have a larger significance: He’s determined to stoke a sense of urgency.

Nothing dies faster in Albany than momentum. Already the old guard is murmuring that things aren’t all that bad: The state budget shows a surplus for 2007, and Medicaid spending has recently shown a minor downtick. What’s the rush to change things?

“For all the hoopla about the Berger report—and it’s a good report,” Spitzer says, “the total annual savings to the state in Medicaid is $250 million. Now, that’s out of a Medicaid budget of $46 billion. Frankly, it’s a rounding error. It isn’t the directional shift we need in terms of Medicaid spending.”

Spitzer is preparing to use his electoral mandate as a wedge to separate Bruno and Silver from their usually lockstep followers.

Spitzer sees the tar pit that will swallow him if he doesn’t hit Albany at a dead sprint. Last week, he staged a press conference to announce new ethics and fund-raising rules that he can implement unilaterally (Bruno swiftly dismissed it as grandstanding). He also showed he’s ready to go over the heads of leadership. “I spent five hours talking to the entire Assembly caucus—all of them,” Spitzer says. “Shelly was there, obviously. But he knows I’m dealing with his members. I’ve met with Joe. But I’ve spoken to lots of members of the Senate too.”

Spitzer’s team has spent hours debating ways to translate his huge electoral win into the kind of governing power that Bruno, Silver, and the lobbyists can’t ignore. One new angle will be helping the public literally watch the government. “I’m going to start insisting that we Webcast all sorts of meetings that until now have been pretty much conducted in isolation,” Spitzer says. “The meetings of the Public Service Commission? Put ’em on a Webcast, so anybody who cares about it will be able to watch it in real time. suny board? Webcast it.”

It’s a nice little start at rattling the “three men in a room” culture that’s ruled the state. But to change anything substantial, let alone everything, Spitzer will need to find more dramatic ways of bringing the 2.7 million people who voted for him into the room if he’s going to pin Bruno and Silver against a wall.

E-mail: chris_smith@nymag.com.