Since her shooting, Gabby Giffords has been an idea as much as a person. What the people around her needed most was precisely what they didn’t have, which was her guidance. Giffords had always been a gifted politician. After she was shot by a crazed gunman outside a Tucson supermarket in January, she became something more: a national symbol of hope and of triumph over the dark forces in American politics.

What was needed was a way of keeping the symbol and the person together, parts of one whole. Gabby Giffords’s survival was nothing short of a miracle—but it left huge questions as to who she was and who she might become. Months into her recovery, she still struggled to speak. And yet her office, and her status, demanded that her views be made known. There was no template for dealing with such a set of circumstances. And so intertwined with the story of Gabby Giffords’s recovery is one about how her staff and her husband learned to answer these questions for her.

Outside the University Medical Center, where Giffords was first treated, the media seemed to materialize out of thin air. C. J. Karamargin, her communications director, arrived at the Giffords district office on Monday, January 10, two days after the shooting; in the course of one day, it had received nearly a thousand messages from the press. The hospital’s staff and her doctors had been in charge of dealing with the media since Giffords arrived. They informed the assembled reporters that her progress was remarkable. She appeared to understand simple commands almost immediately, had opened her eyes, and even recognized her husband’s presence within days—developments that seemed to signal she was on her way to a rapid and reasonably complete recovery, an incredible prognosis given the nature of her injury: a gunshot wound in the left side of her head.

But impressive as her progress was, she was a long way from being able to communicate her desires. Karamargin wondered whether it was right to even open the office, a stubby corner brick building—newly sensitized, he noticed the large exposed windows and lack of security. He talked it over with her staff, and they decided that Giffords would have opened the office; one of her core principles was that no matter the circumstances, tending to constituents was a responsibility that couldn’t be evaded.

Less than two weeks later, another such dilemma arose when Giffords was ready to leave Tucson for rehab in Houston. Should they publicize her route out of town? Her chief of staff, Pia Carusone, who’d rushed in from Washington, was against it. Her political people agreed. Their sense at that point was that the media were driving the story, and they didn’t want that. The media were hungry for an image of Giffords being wheeled into an ambulance. But her staff didn’t want Giffords’s story to be one of illness. “We don’t need the media to know,” said Carusone.

But then Carusone canvassed Team Giffords, the informal council making Giffords’s decisions. The chairperson of this highly unofficial Gabby Giffords committee quickly became Mark Kelly, Giffords’s husband. And he was unequivocal: “Gabby should not sneak out of town,” he wrote in an e-mail. Her route was made public.

After Giffords was put into the ambulance and slowly driven to a local Air Force base, the wisdom of Kelly’s decision became apparent. Rather than a cat-and-mouse game with the national media, her departure became the occasion for an authentic outpouring of emotion. Hundreds of people lined the roads, carrying signs of love and holding aloft images of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Many politicians seem to be products of a committee. Another of the many ironies in the story of Gabby Giffords is that before the shooting, she seemed as unscripted as a politician could be, “open and happy and warm and genuinely interested in people, not just pretend interested,” said one friend. But after the shooting, being Gabby Giffords, the person the public was clamoring for, was a job that required several people, including, most importantly, her husband.

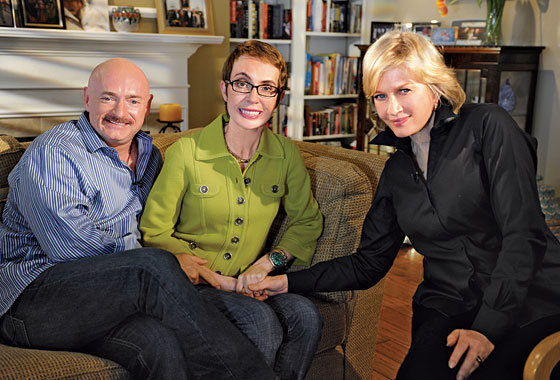

Giffords is being reintroduced to the world this week, with an hourlong Diane Sawyer special and a 575,000-copy first printing of Gabby: A Story of Courage and Hope, a co-memoir with her husband, along with a co-author, Jeffrey Zaslow. Soon, though not immediately, Giffords will have to decide if she plans to seek another term in the House. And if she can’t, or won’t, things may evolve within Giffords’s entourage. Because Giffords and her people really are a team—that’s a legacy of the tragedy. And there has been speculation that if Giffords decides that she’s not yet ready to run for office, her husband could fill the role, given the practice he’s had at channeling his wife. Many Democrats, both in Arizona and Washington, would welcome that.

Another irony in Giffords’s story is that before she was shot, she was thinking of leaving politics. She was torn. She knew how rare her skill was and believed she could make a difference; she sometimes talked about running for governor of Arizona. But she confided to close friends that her chosen business was wearing on her. When she voted for Obama’s health-care plan, someone either kicked or shot out the glass front door of her office. Her tea-party opponent in the last election had called her record “putrid” and even suggested she couldn’t read. Also, there was the constant need to raise money. “She was tired of looking at every stranger as an ATM,” a friend recalled, “wondering how much she could get out of them.”

What she craved, she once told her father, was “a normal life,” which didn’t seem possible given the demands of her and her husband’s careers. Kelly is an astronaut who’s long lived in Houston; the two saw each other maybe once every two or three weeks. “It was a flyby relationship,” said a staffer. In fact, it was managed in part by Giffords’s scheduler. “Marriage is a lot of work,” Giffords said.

And part of a normal life involved having a child. She was going to be 41, which meant it had to happen quickly. Kelly, half a dozen years older, was in less of a hurry—he already has two children from a previous marriage. But they’d come to an agreement: After his next shuttle mission, they would begin in vitro. Giffords had started to harvest eggs, giving herself hormone shots in the stomach in “dirty, filthy airplane bathrooms,” as she told a colleague. Kelly, who’d been treated for prostate cancer, had already stored sperm, and there were already fertilized eggs. But Giffords thought of her job as an impediment. “Nothing was ever black-and-white with Gabby,” says her friend Linda Lopez, “but she did not want to do it anymore. She wanted to have a normal life. She wanted to have a family. She told me she thought this term was going to be her last.”

Some Sunday nights, Giffords looked at her schedule and complained, “I can’t do it all. It’s too much,” to which her staff’s response was, “But you tell them all ‘yes,’ and then we’re stuck.” The weekend of the shooting, though, she’d noticed a hole in her schedule. Her staff set up a Congress on Your Corner event, an impromptu chance for constituents to meet their representative. Jared Loughner, an unmedicated schizophrenic, was one of the people who took notice.

Sometime after 11 a.m. Houston time, Carusone called Kelly at his home, where he was lecturing a daughter about her texting habits. Carusone said she had a terrible message to deliver. “I don’t know how to tell you this, except to tell you,” Carusone began. “Gabby’s been shot.”

Kelly hung up and then stared at his phone—he thought he could have been dreaming. He phoned Carusone back. “Did you just call me? What did you say?”

Soon, Kelly was on a plane provided by his friend Tilman Fertitta, owner of several nationwide chain restaurants and one of the richest people in Texas.

To Giffords’s friends, the pair couldn’t have been more different. Giffords was a kind of Tucson aristocrat, cultured and well-to-do and with access to select circles—one grade-school friend ran against her for Congress, and a high-school buddy helped manage her campaign. (“She had multimillionaires she could’ve married,” her father boasted.) Kelly grew up a blue-collar kid in West Orange, New Jersey, the son of two cops. And there were other dissonances, too. Giffords was attractive and vivacious, constantly making new friends, while Kelly, bald, short, and wide, seemed pleasant and supportive but distant. On his occasional campaign visits, he stood patiently in the background as Giffords held forth. Her friends could see that he was smitten. “She had it all. Beautiful, smart, hardworking, balanced, fun to be with, and she laughed at my jokes,” he once said. It was touching, though these same friends found his jokes a bit old-fashioned: “Have you guys ever packed a suitcase for your wife for a trip?” began one joke. “It’s perhaps the riskiest thing I’ve ever done.”

But their differences were part of their chemistry. “Secretly I think she wanted a macho guy,” said a friend. Around the office she called him “my sexy astronaut.” When they were dating, he’d told Giffords to look in the sky at a certain time, according to Tom Zoellner’s forthcoming book, A Safeway in Arizona. He flew an A-10 Thunderbolt II jet over Tucson and dipped his wing.

On the plane to Tucson, Kelly’s emotions welled up. For a moment, he freaked out in the bathroom—“lost his shit,” one person said. It got worse after it was reported that Giffords had died. Then Kelly composed himself. As an astronaut, “you got to keep your shit together,” said a fellow astronaut. He focused on the task ahead. “I think he made a decision: The only way she’s going to survive is if she’s surrounded by optimism and positive energy and love, and he thought, ‘That’s my job,’ ” said a person who spoke to him later.

When Kelly arrived at the hospital, Giffords was in a medically induced coma. Her head was puffed up and black and blue. Her eyes were swollen shut. Kelly wiped blood from his wife’s face with a tissue and told her, “Hey, sweetie, you look great. You’re doing great. You’re going to be fine.”

The people around Giffords realized from the beginning that managing the story was an overriding priority—but the work was unlike anything they’d ever done before. Karamargin had spent the past five years begging for national media attention—his biggest success might have been getting Giffords and Kelly into the “Vows” section of the New York Times. Now “the media was overwhelming,” said Karamargin, “and seductive.” Now he hit SEND on an e-mail, and ten minutes later he watched the TV in his office as a newscaster said, “This just in on Gabby Giffords … ”

The story had multiple layers. Perhaps the most important one, in political terms, concerned who was most responsible for the violence. One theory had it that Loughner was acting out the violent animus at the core of the far right. The evidence for this, showcased on cable TV, was the fact that Sarah Palin’s PAC, in targeting Giffords for defeat, had drawn a map in which she literally put Giffords’s district in the crosshairs. But while Giffords had been an object of questionable tea-party attacks and had forcefully opposed the recent rhetorical escalation in politics, Loughner is a schizophrenic whose madness is sui generis—Giffords’s father called him, simply, a “nutcase.”

Another problem with this element of the story, from the point of view of Giffords’s advisers, was that a debate over her victimhood made her merely a victim. “We were very conscious that Gabby shouldn’t be absent from her narrative,” explained Karamargin—Giffords should be the author of her own destiny. They decided on a different message. “The arc those early days was about Gabby’s amazing recovery,” he said. “Bouncing back became the narrative.” And, in this telling, good fortune and medical skill hadn’t alone propelled her recovery—it was Giffords’s determination. “She’s working at rehab six hours a day every day—just like Gabby,” who’d never been halfhearted in her life, said Karamargin, recalling the story they were trying to tell. “She’s getting better every day.”

The best part of this story is that it happened, in many particulars, to be true. Soon after arriving at rehab in Houston, she uttered the word toast, which resulted in international headlines. On CBS, Kelly told Katie Couric that she continued to overcome obstacles: Though her right arm was virtually useless, she’d learned to write with her left. She continued to travel with two nurses (and still does), but around the four-month mark she was already walking, albeit slowly and with a crash helmet designed to protect her skull, which was still missing a piece.

Despite the rosy news, behind the scenes some who saw her worried about the expectations that had been created by the narrative. By spring, the rate of improvement seemed to slow. “We saw some very early signs, and so we got optimistic,” said one doctor. “We were expecting a very fast recovery, and that’s not what we are seeing now.” Friends who visited her in late March worried about her struggle to speak. She pantomimed her condition. “Boo-boo, hurt,” she said and motioned to her right side with her left hand.

“What did you have for dinner?” one friend asked.

“Pizza,” she said.

Kelly, who was now always at her side, stepped in—he didn’t believe that progress came from evading difficulties. “No, Gabby, we didn’t have pizza. What did we have?” he asked. Giffords didn’t know what to say. He answered his own question. “We had salad, Gabby, remember?”

Occasionally, an “off-message” comment, as Karamargin put it, slipped into the press. In June, Carusone gave a stark account to the Arizona Republic: “With Gabby, what we’ve been able to infer and what we believe is that her comprehension is very good … Her words are back more and more now, but she’s still using facial expressions as a way to express. Pointing. Gesturing. Add it all together, and she’s able to express the basics of what she wants or needs. But when it comes to a bigger and more complex thought that requires words, that’s where she’s had the trouble.” For Giffords, the divide between cognition and self-expression was deeply frustrating. At one point, she broke down in tears in Kelly’s arms.

Gabby Giffords hadn’t set out to be a symbol—or even a politician. She was “Little Miss Overachiever,” her mother joked. Giffords came from a long line of overachievers. Her grandfather, Akiba Hornstein, was the son of a Lithuanian rabbi who arrived in Arizona, changed his name to Gif Giffords, and opened a tire store just as America embraced the highway system. Gabby’s father expanded the business into a chain of eleven stores. Gabby went to Scripps College in California, then picked up a master’s degree in regional planning at Cornell. Then she landed a high-paying job at Price Waterhouse in New York. “It seemed like the beginning of a grand and glittering adventure in the big city,” she later recalled in a Scripps commencement speech. “Posh apartments, pointy-toed shoes, and maybe even my first martini.”

But when Price Waterhouse offered her a job being a business emissary to Latin America, putting to use her fluent Spanish, the offer precipitated a crisis. Her father, Spencer, told me that he advised her to take it. “Dad, I’ve had thirteen different addresses in the last thirteen years,” she said. “I’ve lived in Europe, Mexico. I want to settle down. I want a place of my own.”

And so a little while later, Spencer called his daughter back with a new plan. “I’d worked for 45 years, six days a week. I was beginning to fall apart. I said, ‘Why don’t you work at the tire company?’ ”

Before the shooting, “she told me this term was going to be her last,” a friend said.

Giffords and her father had a strong, though sometimes contentious, relationship. He was a famously cranky, gruff old man. Robert Reich, Clinton’s secretary of Labor and one of Giffords’s political mentors, once told the press that she might be presidential material some day, a compliment noted by her father. “Oh, no,” he told her. “You’d never be qualified for that.”

And so Gabby said she’d accept the offer, Spencer recalled, “on one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“That you get out.”

“I handed her the keys,” Spencer told me.

At 27, she was back in Tucson, a comfortable town where a person with talent could more readily make her mark. She was president of El Campo Tires, an unglamorous business that she dove into with characteristic enthusiasm. But she didn’t see herself as a tire magnate. “After the company sells, I want to run for office,” she told a friend in the mid-nineties. Giffords, youthful and attractive and with a wide smile, appeared on TV commercials in her cowboy boots, pumping up sales. But her main concern was to get the business in shape to sell—the day of the independent tire dealer had passed. In 1999, two years after she joined El Campo, it was sold to Goodyear.

The commercials turned out to be a showcase and proving ground for her political appeal. The next year, the state legislative district where her parents live opened up, and Giffords was off, “Gabbifying” people, as one political partner put it—she was the most naturally charming politician anyone in Arizona could remember. David Bradley, a state legislator with her, recalls how she lit up a room. “Here comes the rock star,” he said. She hugged, touched, was good with names and biographical details, and always collected business cards. Whoever she spoke to was soon convinced that he was the only person in the world. Said Linda Lopez, another fellow legislator, who later roomed with her, “She never met a stranger.” Liberal voters swooned over her social ideals and her habit of punctuating missives with quotes from Coleridge and Paul Bowles.

But she also won over conservative ranchers. For them, she printed up brochures with, as one campaign aide wrote, “hokey Old West typography and photos of herself riding a horse”—which she’d learned to do in private lessons. “An Arizona original,” they read. She made sure people knew she owned a Glock. In 2002, she became the youngest woman in the history of the State Senate. Then, in 2005, her congressman, Republican Jim Kolbe, announced he would retire.

A friend called Giffords the minute she heard. “I’m running, I’m running,” Giffords shouted. Her district leaned Republican, but Kolbe had been a moderate, too, and she won by a comfortable margin, 25,000 votes. And in 2007, at age 36, she entered Congress, the first female Jewish U.S. representative in Arizona history.

At the time of the shooting, Kelly was planning to wrap up his space career with a final mission: He’d command the last trip of the shuttle Endeavour to the International Space Station. The shooting put his plans on hold. He took time off from NASA and stayed by Giffords’s side, a steadfastly optimistic and loving presence. “She will make a full recovery. I know her really well. She’s going to come back stronger and more committed than ever,” he said two weeks after the shooting, as if he might will her back to health.

In the weeks after the tragedy, Kelly debated whether to bow out of the shuttle mission. But he didn’t want to surrender his own dreams—that wasn’t part of his story line. He’d spent a lifetime preparing for spaceflight, first as a fighter pilot and then as one of 35 people in the astronaut class of 1996—which also happened to include his twin brother. Flying in space is the point of being an astronaut, and in fifteen years Kelly had gone there only three times. When he was tapped to command the last trip of the Endeavour, Kelly wasn’t eager to give that up. Besides, there was the mission to consider. “I’ve been training for this flight for a year and a half. I know it better than anyone else,” he said two weeks after the shooting. “There are mission-success reasons and safety reasons why the best scenario is I go back to work.”

And Kelly told himself that Giffords would want him to go. Even if he couldn’t ask her, he knew she’d understand—it was one of the terms of their relationship. “Just like I don’t have a choice about whether she returns to Congress,” he told reporters, “she doesn’t have a choice in this either.”

In May, he blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida with Giffords in attendance—“Awesome,” she’d managed to say when she heard that doctors would let her travel. NASA kept the press far away from Giffords. Still, someone managed to take a grainy video of her slowly climbing stairs, a crash helmet fastened to her head.

By then, Kelly had come into his own as the co-star and leading man of the Giffords story, not quite as famous as Giffords but getting closer. Soon he was out on the speaking circuit, telling the story of his courageous wife, and his own adventures in space, and asking $50,000 per speech. It was Giffords who now looked on as Kelly held forth. In a Washington ceremony for his retirement from NASA, she smiled and clipped a medal on Kelly’s chest. It was Kelly who was now pursued by the media—with Giffords out of reach, he was “the get,” in TV parlance.

Among the networks, competition to land the first interview with Kelly was fierce, though decorous. Some producers at NBC petitioned Giffords’s staff. But they’d miscalculated. Kelly was the decision-maker, and he favored ABC’s Diane Sawyer, a crafty story shaper. Kelly was given equal billing. She called her segment “The Congresswoman and the Astronaut: An American Story of Love and Strength.”

“It was being presented as a fairy tale,” noted Karamargin with satisfaction. “Ms. Smith goes to meet Buzz Lightyear.”

On June 21, Scribner announced that it had reached an agreement to do a book with Giffords and Kelly. Giffords’s language skills were still very limited, as Carusone told the Arizona Republic two weeks earlier, but Kelly had experience interpreting her thoughts. “After thinking about it, and talking about it, we decided it was the right thing to do to put our words and our voices on paper and tell our story from our point of view,” he told a reporter. It was said that the book would be written with Giffords’s extensive participation. But it is largely Kelly’s book.

“Somebody came to him early on: ‘Going to be five books; people going to earn money from this,’ ” a longtime friend of Giffords’s told me. “ ‘You should think about doing this yourself. Why shouldn’t you earn the money?’ I think he saw the value in that. He was leaving NASA. He’s got two girls he has to send to college. His wife is going to need lifelong medical care. So God bless him.”

In August, Giffords officially rejoined the world of politics, appearing on the floor of the House of Representatives to cast a vote to raise the debt ceiling. The Giffords team had conferred beforehand, and some had been against it—the rationale was that if she showed up for this vote, people would ask why she didn’t appear for others. But Kelly had conferred with Giffords, who’d been following the debate in the newspapers. He informed her aides that it was Giffords’s own choice—she wanted to fly in from Houston and vote—and that he supported it.

It was a powerful moment, as they’d known it would be. She waved her functional arm and smiled—her smile had returned—and brought her audience to its feet, the first time in months the two parties had agreed on anything at all.

But behind the cameras, the picture was more complicated. Giffords’s return to Congress was a one-off; she wasn’t yet ready for sustained social give-and-take. Even as the November 15 release date of the book approached, she was still struggling with her recovery. No doubt she has good days and bad days. In October, a friend spoke to her by phone. The meaning of the conversation was clear—Giffords was trying to explain that she was getting better. But it was expressed in a kind of shorthand: “Boo better,” she said at one point.

Diane Sawyer was again selected to do the interview that would begin the rollout. In its release, ABC had hinted that Giffords would participate—but the network got ahead of itself. In negotiations, “Gabby was never on the table,” a producer explained. Giffords may say a few words, but, as Carusone said, “it’s not a full-length interview.”

The release of the book is another inflection point, and raises a new set of questions about the meaning of her recovery. Before the shooting, she’d been a rising young talent. “She was truly, truly, truly a star … smart, quick, and hardworking. So sincere. So direct,” said a national Democratic strategist. “The Princess Di of southern Arizona,” offered a local commentator.

If Giffords and her team decide that she’s capable of running and she gets back in, the outcome is a foregone conclusion. “If she runs, she wins,” said the strategist. But there’s a flip side: “If she doesn’t run, it’s not a seat easy for Democrats to hold.”

Alongside the narrative of recovery, there are difficult real-world calculations for the Giffords team to make. Democratic leaders hope for delay—the national attention and sympathy that Giffords attracts are fungible commodities in an election year. How extensive her recovery needs to be in order for her to govern effectively is still being worked out—does she really need to be able to deliver a speech from the floor? Indeed, some of the crucial functions of her campaign work almost automatically these days. She effortlessly raised money without attending a single fund-raiser—her friend Senator Kirsten Gillibrand helped, in case she decides to run. As of the last filing, she has collected over $800,000. If she didn’t run, the money could be spent on other candidates.

The fact that Giffords hasn’t yet declared her intentions is itself an element of her political power. No one dares declare a candidacy or raise campaign funds while this courageous woman fights against the odds. A website, giffordsislying.com, that had backed her opponent now shows a single page, a prayer for her swift recovery.

The book changes this equation. No doubt, it will generate positive feeling toward Giffords, but it could also limit her options. “It will draw attention to her ability to run,” said one staffer.

And her recovery, impressive as it has been, is not over. “If she had to declare today, she couldn’t run,” said a longtime friend.

For some, reclaiming her old seat has become the sine qua non of her recovery, part of its definition. In the book she offers a simple, heartfelt declaration: “I will get stronger. I will return.” But there are other options if it takes longer than expected. One of the daydreams floating through the corridors of Washington these days is that Kelly will step in. “He’s really accomplished. And there’s the popularity that both of them enjoy. Plus his biography would make him compelling,” said an influential Democrat. Kelly was already speaking for her, endorsing candidates on her behalf, which led to media reports like “Mark Kelly and Gabby Giffords support …” It was a version of Bill Clinton’s buy-one-get-one-free boast about Hillary.

The Democratic Establishment reached out to Kelly when Republican senator John Kyl decided not to seek reelection. Kelly rebuffed them at that point. (Now Dr. Richard Carmona, a former U.S. surgeon general and close Giffords ally, is going to run for the seat.) “She’s the politician in the family,” he said recently. “I’m the space guy. And I see no reason to change that …”—he left the door open—“… now.”