Almost exactly 48 hours before the Armstrong Ranch massacre, Dick Cheney delivered a dinnertime oration at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference down in Washington. I must say he didn’t look like a man on the verge of going postal (no more so than usual, that is). Actually, he seemed calmer and sunnier—less scowly, less snarly, more pink of cheek—than he has in quite some time. When he trundled up to the podium, he was greeted with a lusty ovation. With a curl of his upper-left lip that nearly qualified as a smile, Cheney said, “Getting a reception like that almost makes me want to run for office again.” A well-timed beat. “Almost.”

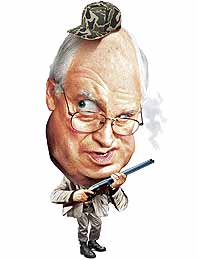

A little more than one week later, it’s difficult to imagine Cheney joking about tossing his hunter’s cap back in the ring and pursuing higher office. Indeed, it’s difficult to imagine him joking about much of anything. The events surrounding Cheney’s errant-birdshot wounds of his quail-flushing companion Harry Whittington—events horrible and hilarious by turns, casting in stone a dark and scheming image long gestating in the public mind—are of a kind from which no politician could ever truly hope to recover. Indeed, the question now is whether Cheney will manage to serve out his term.

It’s a question, of course, that’s been asked before—asked and answered, you might say. Since George W. Bush took office, rumors of Cheney’s impending resignation have bloomed in the capital as reliably as the dogwoods. In 2004, he was going to be dumped for the sake of Bush’s reelection. In 2005, he was on the way out on the cusp of Scooter Libby’s indictment. Each time, the gossip came to nada.

And so it would be natural for sobersided people to dismiss the current round of speculation (which, for the record, is being indulged in not just by the lefty blogosphere but by paid-up conservatives such as Peggy Noonan). Certainly that was the reaction of White House press secretary Scott McClellan, who dismissed any mention of the R-word as “absurd.”

Yet in truth the case for Cheney’s resignation is more compelling today than ever. Now, let’s be clear, the point here isn’t that accidentally shooting a septuagenarian in the face is automatically a firing offense. The point is that, politically speaking, from the perspective of Bush and the Republican Party, it’s hard to argue that Cheney isn’t more trouble than he’s worth.

Start with the fact that Cheney, irrevocably, has gone from being a figure of fear to being a punch line—and not just in the hands of Leno, Letterman, and Conan. “I’m really glad to be here,” Microsoft chairman Bill Gates said the other day at a conference in San Jose. “My other invitation was to go quail hunting with Dick Cheney.” When someone as terminally unfunny as Gates can score laughs at your expense, you know you’ve crossed the pop-cultural Rubicon into Admiral Stockdale territory.

The mockery would be easier to shrug off were Cheney a broadly popular figure with the American electorate. But according to the most recent CBS–New York Times poll, the vice-president’s numbers—23 percent of voters view him favorably, 41 percent unfavorably—are even worse than Bush’s, a noteworthy achievement. Owing to his intimate involvement in a litany of policy cock-ups and politico-ethical scandals (Iraq, Halliburton, Plamegate), Cheney has long been, as Noonan put it last week, “the administration’s hate magnet.” Now he’s become a vivid symbol of its incompetence as well—the poster boy for the Gang That (Literally) Can’t Shoot Straight.

And let’s not forget that Cheney’s political albatrossity is only destined to grow more pronounced next year when the Libby trial commences. In the furor over Quailgate, it was easy to forget the recent disclosure that Libby had told the grand jury that his “superiors” had authorized some of his intelligence leaks to journalists. And it was easy to overlook Cheney’s startling suggestion in his interview with Brit Hume that, as vice-president, he has the power to declassify information unilaterally. Both revelations are ripe with legal import for Libby. And both are brimming with political implications for Cheney and Bush—none of them positive.

In the face of all this, the substantive argument for keeping Cheney on is the same as it’s always been: He’s Bush’s brain, the indispensable man without whom the administration would essentially evaporate. And yet, in any number of areas of policy where Cheney’s influence was once central, his presence now seems superfluous. On Iraq he’s been usurped by Condi Rice, on energy by whatever anarcho-syndicalist inserted into the State of the Union that business about how America is “addicted to oil.” (At CPAC, Cheney made a point of growling about new refineries and drilling in Alaska; perhaps out of fear that he would choke on the word, he failed once to mention ethanol.)

The political argument for Cheney’s retention is equally familiar: He’s beloved by the Republican base. And no doubt there’s truth to this. “I don’t know if they love him, but they admire him,” says Marshall Wittmann, a former staffer to both the Christian Coalition and John McCain. “They admire him because he’s steadfast, and he makes the right enemies.” Yet the conservative operative Grover Norquist points out that elements of the base are distrustful of Cheney’s expansive vision of foreign policy (“They worry whether Cheney’s war will swallow Bush’s presidency”) and his disdain for civil liberties (as evinced by his avid defense of the wiretapping program). When I asked Norquist about Cheney’s rapturous reception at CPAC, he replied, “When Cheney or Karl Rove is up there, what they’re really applauding is the president.”

For Bush, then, the political downside of shedding Cheney would be negligible. But the upside would be great. First and foremost, it would give him a chance to anoint a successor in the person of his new VP.The possibilities here are endless, and endlessly fascinating. Among GOP players, the assumption is that the immediate front-runner would be Rice, whom Bush manifestly adores, and who in turn is viewed with remarkable enthusiasm by the Republican grass roots. Just below her on the list is Senator George Allen, a Virginian whose propensity for southern-boy macho affectations (not only does he wear cowboy boots at all times and speak of his reverence for the fallen nascar hero Dale Earnhardt Sr., he also dips tobacco, carrying a spit cup with him everywhere) exceeds even Bush’s. Further down, there’s Senator Bill Frist, whose last known residence was Rove’s hip pocket. (As for McCain, I won’t go there; I get enough right-wing hate mail already.)

By choosing any of these characters, Bush would impose order on what promises to be a fractious Republican contest in 2008—and there’s nothing the GOP craves more than order in selecting its presidential nominees. And he’d be substantially increasing the odds that his policies, in particular on Iraq, would be carried forward.

So will Cheney go? Wittmann suspects not. “The fact that Bob Herbert wrote that he should resign guarantees that he’ll be there through 2009,” he says with a laugh. “The psychology of this administration is, the more the chattering classes suggest something, the less likely it is to happen.”

“If Jeb Bush stepped into the field,” says Grover Norquist about the 2008 race, “it would be all over.”

Another explanation comes from a longtime friend and political adjutant to Bush, whom I e-mailed the other day. Wouldn’t the administration be better served politically, I asked, if Cheney were to be replaced?

“I hear you,” replied this person. “The answer is maybe, but it will never, ever, happen. In Bush World, loyalty trumps political gain every time.”

Fair enough—but it’s reasonable to wonder whether, in the case of Bush and Cheney, loyalty is a two-way street. Over the course of the past year or so, as first Plamegate and now the Deadeye Dick imbroglio unfurled, it’s become abundantly clear the vice-president views himself as a solo act, accountable and answerable to no one, Bush included. Imagine that Al Gore or Dan Quayle or, for that matter, Bush 41 blasted someone in the head with birdshot. Now imagine them disregarding the wishes of the White House press office about informing the media. Imagine them not phoning their bosses about the incident until two days later. Impossible? Duh. But that was Cheney’s course—and one that hardly falls under any definition of loyalty.

George W. Bush may not be the brightest bulb in the chandelier, but he’s not, you know, an idiot. So let us postulate that there might be something deeper, even Machiavellian, at work should he decide to stick with Cheney. Perhaps Bush sees no mileage in anointing a front-runner for the Republican nomination. Perhaps he prefers to keep the field jumbled, on the chance that a contender he likes better than anyone in the current crop were suddenly to enter the fray. Perhaps he thinks (or even knows) that the contender might be his brother Jeb.

Grover Norquist, among other Republican pros, doesn’t discount the possibility. “If Jeb Bush stepped into the race, I believe it would clear the field; it would be all over,” he says. “He’s the best governor in the country. And the argument against him running is that you can’t have a dynasty. But the one year when Jeb Bush can run and no one can seriously raise that argument is the year we’re running against Hillary Clinton.”

Fantasy? Conspiracy theory? Well, it’s certainly a moment when both are finding fertile ground. But if, a few months hence, Cheney is replaced with a fresh vice-president, it won’t be the least bit wacky to conclude that Jeb is determined to sit out 2008. If Cheney hangs on, though, what lies beneath will remain obscured. It may be all about loyalty. But these are the Bushes, after all. It may be even more about family.

E-mail: jheilemann@gmail.com.