The morning after Super-Duper Tuesday, Barack Obama held a press conference in Chicago, where he was asked an obvious question: Isn’t it a mite disingenuous for him to continue to cast himself as the underdog in his race against Hillary Clinton? “I’m never disingenuous,” Obama deadpanned. “I think we are less of an underdog than we were two weeks ago. Two weeks ago, we were a big underdog. Now we are a slight underdog.” Obama added, with a smile, “I think we are turning out to be a scrappy little team.”

Never let it be said that Obama is a man without a sense of humor. Put aside his performance the day before, when he won a majority of the states and a majority of the delegates (or so his side maintains) up for grabs. Put aside the fact that in January his campaign raked in an astonishing $32 million and that another $6 million arrived in the following 24 hours. Consider instead that on the very same day, Clinton was forced to acknowledge that she’d injected $5 million of her own money into her operation, with possibly more self-funding to come. Consider that some of her senior strategists were offering to work without pay. Consider that her team was asking, pleading for more debates-and gamely, if lamely, trying to label Obama as the “Establishment candidate.”

Now, honestly, which of these campaigns sounds as if it’s riding high? And which sounds like it’s reeling?

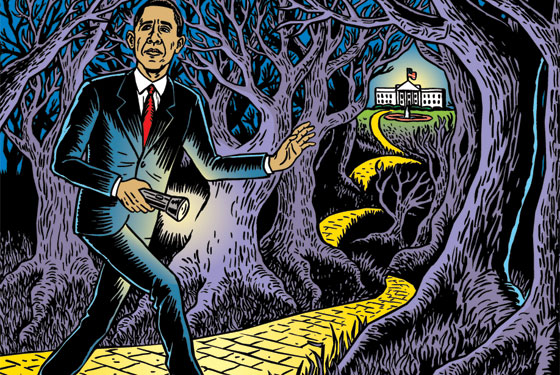

Unwelcome as it may be in terms of spin, the reality is that Obama stands as the front-runner in the race. The question is whether he can translate that position into the nomination. And here the answer is far less clear. Though the path that could transport Obama to victory isn’t difficult to discern, it’s a road pockmarked with potholes. Also one that appears increasingly likely to carry him and his party into terra incognita—maybe even past the end of the primaries and all the way to the Democratic convention.

Beyond his own estimable political skills, the greatest advantage that Obama has going forward is money. The resources required by the states that lie ahead may seem like a drop in the bucket compared with those demanded by Super-Duper Tuesday. But we’re still not talking chump change. To run effective air and ground operations in Ohio, Texas, and Pennsylvania, says Jonathan Prince, a top adviser to John Edwards, “a serious campaign probably needs to spend around $5 million a week.” And that’s just three—albeit the most delegate-rich three—of some two dozen contests yet to come.

Making a nut of virtually any size should pose few problems for Obama, whose team is reportedly on track to raise another $30 million in February. From the start, his campaign has assembled a small-donor machine that, as David Axelrod put it to me, “lets us build ever-expanding concentric circles of support.” But no such mechanism exists on the Clinton side, which rested its vaunted fund-raising apparatus on the backs of big contributors, most of whom are tapped out. While the campaign is working feverishly to get its online buckraking pistons pumping—and, indeed, in one day last week, they generated $4 million—it finds itself scrambling to play catch-up. Might Bill Clinton have to spend some of the $20 million he’s reportedly owed from Ron Burkle on radio ads in Cleveland or Fort Worth? The mind reels, but, hey, who knows?

Obama’s second major advantage is the calendar. Between Super-Duper Tuesday and March 4—when Ohio, Texas, Vermont, and Rhode Island vote—nine contests were set to take place: four caucuses (a format Obama has dominated), four primaries with a big percentage of black voters (ditto), plus the primary in Wisconsin, in which independents can vote (double ditto). But Clinton’s people conceded this week that it was possible that their candidate would win not one of them. And if that or something like it occurs, sheer momentum might propel Obama to a sweep on March 4.

This is Obama’s dream scenario, but it may also be a fantasy. From Iowa onward, Obama and Clinton have each assembled a formidable electoral coalition. Hers: downscale Democrats, especially women; senior citizens; Hispanics. His: upscale Democrats, especially men; independents; blacks; young voters. The trouble for Obama is that the demographics of both Ohio and Texas aren’t particularly favorable to him. In 2004, just 10 percent of Democratic-primary voters in Ohio earned more than $100,000 a year-and fully25 percent of those who voted in Texas were Latino. Moreover, HRC will have the bulk of the Establishment support (Ohio governor Ted Strickland is behind her, for example) in both states.

Yet no matter who prevails in Texas or Ohio, there’s a reasonable chance that the outcome will settle nothing. Why? Because, as we all were instructed ad nauseam by the TV bloviators on Tuesday, the Democratic process is governed by the principle of proportionality—which means that, unless one side really clobbers the other in a given state, each of them winds up with a roughly equal number of delegates. The intent of proportionality is to protect genuine underdogs. But in a fight between heavyweights, the effect, as Clinton communication czar Howard Wolfson puts it, is “more to avoid picking a nominee rather than picking one.”

The implications of all this are firmly grasped in Obama-land. This week, the campaign inadvertently released a spreadsheet containing a detailed projection of the outcomes of the remaining primaries and caucuses. It predicted that Obama would win nineteen of them, but that he would lose by between four and seven points in Ohio, Texas, and Pennsylvania. The bottom line? After the final votes had been cast in Puerto Rico on June 7, Obama would emerge with 1,806 delegates and Clinton with 1,789-both a couple hundred short, that is, of the 2,025 necessary to nail down the nomination.

It’s possible, to be sure, that the Obama spreadsheet was leaked intentionally in a bid to set expectations. But the assumptions undergirding the projection strike most political professionals as credible. More to the point, its overall thrust, that in all probability the race is headed toward deadlock, is accepted by the Clinton people. “It is likely that no side will gain an appreciable or significant advantage in overall delegate counts between now and March 4, past March 4, even past April,” Wolfson says. “For all of those who, for cycle after cycle, wished for a battle that goes to the convention…you could be looking at such a contest here.”

If the race does indeed unfold that way, the cards that Clinton intends to play are already face-up on the table. First, she plans to rely on her advantage among the nearly 800 party panjandrums—elected officials, state chairmen, national committee members—known as superdelegates, who can vote any way they choose. Clinton currently claims a 259-170 lead among these people, with the remainder still planted on the fence; the received wisdom holds that aggressive chit-calling by Clinton and her husband will keep her ahead among this crowd all the way until the end. But if that lead doesn’t prove sufficient to put Clinton over the top, her campaign is already agitating loudly that the delegates from Michigan and Florida—two states that were penalized by the DNC for moving their primaries forward and that Clinton won handily in the absence of any real competition—be seated at the convention in August in Denver.

Obama’s counteroffensive against the Clintonian Michigan-Florida maneuver is already under way. His campaign correctly argues that to seat those delegations would make a mockery of the DNC, the rules it set, and the entire process. In Michigan, only Clinton (along with Chris Dodd) left her name on the ballot—and thus to count the delegates chosen there would unfairly penalize Obama. As for the superdelegates, Obama began limbering up for that battle the morning after Super-Duper Tuesday, previewing the pitch that he intends to make should the occasion warrant it. “If this contest comes down to superdelegates, we are going to be able to say we have more pledged delegates, which means the Democratic voters have spoken,” he explained. “Those superdelegates, those party insiders, would have to think long and hard how they would approach the nomination.”

The trace of confrontation in Obama’s tone suggests how ugly things could get in Denver if Clinton attempts to take possession of the nomination this way. It hints at the crisis of legitimacy that could explode, ripping the party in two. In these circumstances, the moral responsibility for avoiding such a crisis would lie squarely with Hillary and her husband, but the political challenge, and opportunity, would rest with Obama. The superdelegates are, it’s true, the embodiment of the Democratic Establishment. But in case you haven’t noticed, much of that Establishment has lately turned its back on the Clintons—or put the boot in them. Many, maybe most, of the superdelegates are open to persuasion. A surprising number may even be ready to “turn the page.” What they want most of all is a Democratic nominee who can win. If Obama fails to bring enough of them over to his column, it should tell us something: That the man sure can give a hell of a speech, but he can’t close the deal.

SEE ALSO

• Heilemann Breaks Down the Super-Duper Tuesday Numbers

• Why Huckabee Could Be McCain’s solution

E-mail: jheilemann@gmail.com.