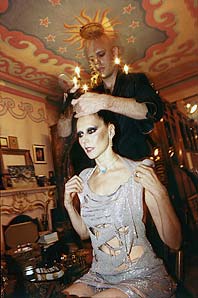

The makeup guy is a total absolute geeenius. Just look at the way he swoops and orbits around her pale, narrow face—a surgeon with the glittery periwinkle eyeliner, his hands seemingly laser-sighted as he carefully crimps a pair of very long, very fake eyelashes. Over the years, legions of theatrical boy-men have hovered over her face with their tiny wands and top-secret compacts, but she digs Bruce like no other. The man is a guru. A magician. With Bruce around, you would never guess that Susanne Bartsch is 55 years old and has, minus a brief hiatus to give birth to a child, been going out nightly for the past four decades.

“Bruce, seriously, you are a total, absolute geeenius,” she says, sitting amid the shabby clutter of her apartment in the Chelsea Hotel. And then, into her cell: “Junior! Are you still there, Junior?”

Junior is Junior Sanchez, the D.J., “an amazing person, very connected with Madonna, whom I adore.” Tonight is a Tuesday, the evening of Susanne’s party at Happy Valley, a club on East 27th, where she is trying to wrangle Junior to spin later. Consider it a testament to her prodigious hostessing powers that until recently, Happy Valley was a nocturnal no-man’s-land: desolate and struggling, not talked about by the people who talk about these things. Then Susanne decided to throw a party, something she hadn’t done since the late eighties. Suddenly, you started hearing the expectant murmurs: Susanne Bartsch—the fabled underground iconoclast, the promoter whose decadent nights cured New York of its post-disco hangover, the woman once anointed the “Pied Piper of nightlife”—had emerged from the exile of motherhood to indulge in a long-awaited encore. “Of course people are buzzing about Susanne,” says her friend Ian Schrager, the Studio 54 owner turned hotelier. “Throwing parties is in her DNA. She is a true icon of the night, someone who goes down in the nightlife hall of fame.”

Getting ready for an event is, for Susanne, an event in itself: multiple phones ringing, music blaring, people coming and going as if moved through her apartment via conveyor belt. Rarely does anything go according to plan because rarely is there a plan to go by. Take Junior: He is supposed to spin later, but, then again, he was supposed to spin last week. “You better not be stuck in the stooodio with that bloody Shakeeera again,” Susanne scolds him over the phone. She is from Switzerland, ended up in New York by way of swinging London, and her Teutonic accent remains severe, every third word drawn out like a piece of taffy, something to savor and flaunt. As she speaks, in comes Charlie, her hair guy, who starts grafting a flowing black synthetic wig onto Bartsch’s head with the precision of a topiary artist.

“Trust me,” he says. “The profile is going to be fierce.”

“Oh, Charlie, that’s geeenius!” And to Junior: “Promise you’ll be there? You will? Geeenius!”

The desire to throw a weekly party again first came on like an itch, a tickle of loneliness. It’s not that Susanne had disappeared from nightlife completely—there were fashion parties, Halloween balls, New Year’s Eve in Miami—but she hadn’t been a regular fixture in years.

“I missed being out,” she says, “missed seeing people.” There are more altruistic motives for her return as well: “The state of nightlife today, it’s dismal!” she says. “The clubs are soulless, dollar-driven. There is no energy, none of the mixing that I love.” She despairs of what’s become of her beloved nightlife, co-opted by post-frat players standing in line at Marquee with masochistically tweezed postpubescent girls. While she was gone, clubs morphed into slick terrariums of exclusion, segregated by who could access the VIP area, who was trust-funded or hedge-funded enough to drop $300 for a $15 bottle of vodka, who was moderately famous. It made Susanne depressed, which, as with any artist, is when creativity strikes.

She started wondering if she could re-create something like the venerated nights she hosted nearly twenty years ago, something like her notorious monthly Thursday-night party at the Copacabana, which is where you went to witness Marc Jacobs and Malcolm Forbes mingling in an undulating sea of trannie hookers and, as Susanne wistfully remembers, “a stripper who smoked cigarettes with her pussy.” Anita Sarko, a D.J. and onetime Copa regular, remembers Susanne as the ringmaster presiding over a lawless carnival: “She had a way of taking all these weirdos, giving them a place to congregate, and as a result she turned them into icons.” The parties were one of the reasons that Simon Doonan, the creative director of Barneys New York, devoted a chapter of his book Wacky Chicks: Life Lessons From Fearlessly Inappropriate and Fabulously Eccentric Women to Susanne. “I used to tear up to the Copa after finishing the windows at the store,” he recalls. “She had another stripper named Lady Hennessey Brown who could lactate! It was fabulous! Susanne is really the first person to make sleaziness groovy. She’s a visionary that way, you know?”

By the early nineties, Susanne had carved out an eccentric niche for herself as the maternal figure to self-orphaned club kids living lives their real mothers didn’t understand. Then things got tricky. Susanne became a real mother herself. Among the bustle in the apartment is a precocious, curly-haired 11-year-old named Bailey, Susanne’s son with David Barton, her second husband, a man best known for a chain of gyms that bear a passing resemblance to his wife’s parties. Bailey was born in 1994, a year before the couple married in a Playboy-sponsored ceremony with Betsey Johnson and Ingrid Sischy among the 43 bridesmaids. It was then that Susanne retired from throwing regular parties: nothing formal, just a dignified fade from the scene. But Bailey is now a sixth-grader at St. Ann’s—mature enough that his mother doesn’t feel guilty leaving him with his longtime nanny on Tuesday nights when she undergoes her “transformation from housewife to glamourpuss.”

A few years back, HBO flirted with the idea of creating a reality show around Bartsch, her family, and her entourage of rakish groupies. (“Before The Osbournes,” Susanne likes to point out. “Before anyone, really.”) The show was nixed, but given the dizzying surrealism of the party preparations, it’s hard to understand why. Here comes Zaldy, her clothing guy, who lives downstairs and designs Gwen Stefani’s L.A.M.B. collection. “Oh, this is going to look fabulous,” he says, showing Susanne tonight’s outfit: a green velvet maiden dress, baroque gold-plated belt, cast-iron unicorn pendant, burgundy leather lace-up stiletto boots.

And here comes David Barton, who has a bodybuilder’s spring-loaded physique and spiky, frosted bangs falling over his eyes like stalactites. “Rufus is doing really well at the gym,” he says as his wife gets dressed—Rufus being Rufus Wainwright, the singer. Though the couple seems perfectly matched—both are guided by instinct, both are fond of praising one another’s bedroom technique to near total strangers—the relationship hasn’t always been an easy one. In 1999, the two separated, their mutual obsessions with work not mixing with their outsize personalities; they reconnected in the wake of September 11. All has been congenial since, though Susanne still refuses to give Barton back his closet space.

As for Bailey, he used to find his mother’s fashion proclivities somewhat dismaying (“Bailey would say to me all the time that when I got into drag I looked oooogly,” says Susanne), but now he describes her as “funny” and leaves it at that. At present, he wanders over and slumps into the overstuffed couch, his feet propped up on the driftwood coffee table where Awakening the Buddha Within sits atop The Economist.

“Hi, darling. How was school?” Susanne asks, talking simultaneously to the club via cell: “Yes, Junior swears he is coming … ”

“I read a poem in class that everyone loved,” says Bailey. “The assignment was to write a poem that made no sense but had a deeper meaning. Mine was about death. It was very dark. It was called ‘The Upside of Saying Good-bye.’ ”

“Oh, that’s excellent, darling.” And then: “Hey, Zaldy? Can we make the hem shorter?” Zaldy drops to his knees for some ad hoc alterations.

“The whole celeb thing is getting on my nerves. People don’t even care about the décor. You can give them a toilet—if there’s a celeb there, it thrills. I like Brad Pitt, but he’s not going to make my event, you know?”

“Mom?” Bailey jumps in, yawning, the time nearing eleven.

“Yes?”

“Permission to go to bed?”

“Of course, darling. Give us a kiss good night.”

Another twenty minutes is spent on the hemline: pinning, furling, repinning, refurling. In the end, the dress has been reduced to such a flimsy scrap of fabric that it’s impossible not to notice that, at 55, Susanne Bartsch looks mighty fit in a black thong. With her pixie hips and alabaster skin, she looks pretty spectacular all around. Has she had any … surgical assistance? “Oh, I want to get it, but I don’t have the balls, darling,” she deadpans. “Hell, I’ve had a good life. It’s okay for people to see it in my wrinkles.” With that she bends over, gives her trim hips an ironic wiggle, and heads out to Happy Valley.

When I walk into the room, I get so inspired,” Susanne says as she approaches the club’s anonymous façade. The street is rain-slicked, deceptively deserted. “I see the right people, I see everyone having a good time, I see someone dancing on the bar. And everything just gels, right?”

But until that moment, she is consumed by an almost toxic anxiety. Probably it has something to do with returning after such a long absence, having a legacy to uphold. Walking down the dark corridor leading to the main room, the walls throbbing with bass, she can’t help but wonder: What if the first few Tuesdays were a fluke? What if nightlife has become resistant to her philosophy, and now her cynical children have migrated elsewhere, muttering that Susanne Bartsch isn’t what she used to be, and right now she’ll open the door and be forced to confront the dark reality that—

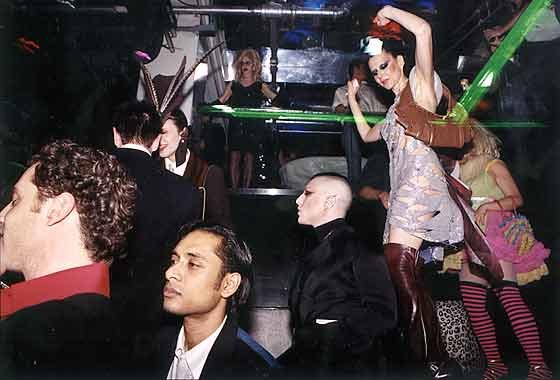

Christ! Look at them all! It’s barely past midnight, and already the place is teeming with people, hundreds of them, all pressing against her, all chanting the same chorus: “Susanne!” “Oh, Susanne!” “Let’s go say hi to Susanne!” The music is a riotous fusion of electronica and rock, genres as mashed and disparate as the bodies colliding on the dance floor. There really is one of everyone in here—like swimming around a petri dish labeled NO, BABY, THIS IS NEW YORK! You’ve got gay boys and straight boys and closeted boys; reptilian model girls who’ve stripped down to tissue-thin panties; uptown businessmen in pin-striped suits with loosened ties; hollow-cheeked hipsters in retro sneakers; old-school and new-school club kids; a moon-faced midget; ambiguously gendered Asian hotties in hot pants; three less-than-sober gossip columnists; and a sprinkling of drag queens giving a sequined nod to the old days. The democracy of it all! That’s what Susanne loves the most: that no one owns Happy Valley, that a kind of jubilant, pheromonal anarchy presides. This is by design, of course. There is no cover, no “list” at the door. You heard there was a party? Oh, excellent! Come on in—

“Come, come!” says Susanne. “Time to say hello to everyone!”

The lighting is almost doctor’s-office bright. It gives everything a weird spotlight feel, everyone on a stage, performer and audience merged into one. The balconies are neon-trimmed. The D.J. booth is a deliberately kitschy disco ball the size of the studio apartments most people here have escaped for the night. The whole place feels pleasantly slapdash: not so much a self-conscious homage to the eighties as a club that was shuttered in ’86 and has been lying dormant for two decades, collecting dust until an hour ago, when someone figured, what the hell, let’s open the doors and see what happens. (The effect is the brainchild of designer Jeremy Scott—another total geeenius.) In the neon cage hovering over the dance floor, a white dude with an Afro drops his track pants and gyrates to remixed Franz Ferdinand as a clique of girls with polyurethaned lips cheers him on. “It’s good, right?” says Susanne. “Like if you want to get naked for some reason—fine, you can! This is what I try to create.”

How Susanne became a professional party girl is an object lesson in the power of charm, momentum, serendipity, and a city that once operated as a laboratory for creatively minded misfits looking for a place to experiment. At 17, she left her middle-class Swiss family for London, soon finding herself hanging with Mick Jagger at Speakeasy, accessing Jimmy Page’s estate with her own key, and starting a boutique knitwear company that catered to bands and semi-anonymous “It” girls like herself. She moved to New York in 1981 when a painter invited her to spend Valentine’s Day in his apartment in the Chelsea Hotel. He ended up leaving her for another woman; she never left the apartment. She started importing avant-garde clothing from London, selling it out of a tiny boutique on Thompson Street, introducing New York to figures like Leigh Bowery and John Galliano, and eventually expanding her store in Soho, with Limelight owner Peter Gatien as her silent backer. When that didn’t work out, she noticed another opportunity for persona expansion: a club called Sauvage opening in her neighborhood. She approached the owner about throwing a party. Did anyone have a more eclectic, ready-made guest list?

A white dude with an afro drops his track pants and gyrates to remixed Franz Ferdinand. “It’s good, right?” says Susanne. “Like if you want to get naked for some reason— you can! This is what I try to create.”

“Now let’s go see if Junior is up in that disco ball,” Susanne says. But that twenty-yard journey is going to take two hours. She keeps getting swarmed with people she either knows or sort of knows or pretends to know—it doesn’t matter. Some are her age, stalwarts from the Copa days emerging from hibernation. Others are vacant-eyed androgynous children wearing fingerless gloves and leg warmers, their eyebrows pierced, their fishnets meticulously torn. “I knew the kids would be wrapped around her finger,” says Kenny Kenny, her longtime doorman. “I gave it three months. It took three weeks.” Among them is Mark Hunter, a 20-year-old photographer who runs a Website called The Cobrasnake, the New York Social Diary for hipsters with headbands. “Man, I’m used to going to indie-rock parties,” he says. “This is just a crazy mix. I like all the hot model girls who shouldn’t be here and all these weird old people. I wasn’t even familiar with Susanne Bartsch. Just heard she was some legendary party person. It’s fun to feel like you’re back in the eighties, you know?”

Well, sort of. You do notice a number of asymmetrical haircuts and more than a few pairs of jelly sandals. And maybe there is something to the notion that the times are reminiscent of Susanne’s Copa days: a Bush in the White House, a Republican paranoia in the air—and maybe this has stoked a latent rebellion among a certain set of New Yorkers eager for an excuse to gleefully give the finger to the era in which they’re stuck. Maybe. But that’s not why Happy Valley works. Susanne’s latest party does not have the tragic feel of a reunion tour. There are plenty of Mark Hunters here, kids who don’t know Susanne Bartsch from Oliver North. As Heatherette designer Richie Rich, who just showed up, puts it, “People here, they don’t even get what Susanne meant in the eighties. And that says something, you know? Like the kind of impact she can have just by what she does. She is so important to the city. I’m telling you, man, she is like the Statue of Liberty.”

Junior? Jooonior!”

The Statue of Liberty is climbing the ladder leading into the disco ball. Yes, Junior showed up, as promised. Look at the way he mans the turntables, toggles the dials, adjusts the equalizers—totally geeenius! Susanne gives him a kiss, thanks him for coming. He looks down on the dance floor with the gravity of an air-traffic controller. From this vantage, you notice something else about Happy Valley: the absence of a VIP area, no encaged B-list celebrities being gawked at like creatures in a petting zoo. “The whole celeb thing is getting on my nerves,” Susanne vents. “It’s gotten to the point where people don’t even care about the décor. You can give them a toilet—if there’s a celeb there, it thrills. I like Brad Pitt, I’d like him to come, but it’s not going to make my event, you know? I know famous people. I never use them. It’s not my style.” That said, she is pleased to note that John Waters recently reserved the space for a party, and the other night, Ashley Olsen’s people called up—same with Lindsay Lohan’s—making cryptic inquiries about when might be the best time to stop by. But that is the effect, darling, not the cause. “To me, it’s about uniting,” she says, “about rejuvenating, saying everything goes.”

Creating such an environment is easier said than done. The club gives Susanne a budget of just under $5,000 a week to produce the event, and from that she pays her doormen, the D.J., security, her constantly changing stable of co-hosts like Amanda Lepore (the surgically enhanced “muse” of photographer David LaChapelle), and herself. She convinces all of them to work for a fraction of their regular fees. “One thing about Susanne,” says Happy Valley owner Joe Vicari, “she’s very good at keeping costs down.” Still, the club lost close to $20,000 during the first month of Susanne’s parties, before word got around and Tuesday night took off. Now they do a brisk business at the bar, netting between $10,000 and $20,000. But the party is more about branding than boosting the bottom line. For the club, the publicity generates crowds on weekends, when Happy Valley reverts to the typical cover-charge, bottle-service model. For Susanne, whose real money comes from planning corporate events, the party is a reminder to fashion and media people that she still has the touch.

From the D.J. booth Susanne stops by the bar and grabs a bottle of water, sipping it in quick swigs, then heads up to the balcony. She used to drink a beer or two when she was out, but no longer. As for drugs? “I’m a bit of a pussy, really,” she says. “I’ve had a line of coke here and there, but it’s not my thing. If I smoke pot—well, I think it’s good for sex, this is true. But I’ve always had a good sex life, so I don’t really need it.”

Upstairs, she makes her way to the neon cage above the dance floor, recently vacated by Half-Naked Afro Man. She steps inside. It’s two in the morning now, and people are still piling in. “This, really, is what I love,” she proclaims. “I love to dance!” The shiny happy souls down below look up and cheer, catching the invisible kisses Susanne blows at them. Look, there’s Amanda Lepore! And Michael Musto! And there, on the oversize stairs rising in the middle of the dance floor, is a pudgy, middle-aged man in battery-powered sunglasses who—right here, right now—is in the only place on Earth where he feels at home! It is exactly the sort of moment that Susanne craves. The sort that causes a psychosomatic flashback to 1989, when she threw what she still considers her crowning achievement: an aids benefit called the Love Ball that raised $400,000 and introduced a then-unheard-of dance called voguing. “Madonna came, and next thing you know, there’s the ‘Vogue’ video,” Susanne is fond of saying. But incidentally initiating a fad is not what lingers in her mind. What she remembers is something more intangible, a feeling she’s still chasing. “I stood there on the stage and felt like a transistor radio,” is how she phrased it the other day, though she could have been describing herself right now, as she looks down on all her sated children at Happy Valley. “I put my arms out, and I felt all the energy of the people flowing into me and then back out. There was so much love. It was beautiful.”

Speaking of love, at three o’clock David Barton shows up, as he does every Tuesday, to “support what I do,” as Susanne puts it. Barton takes her hand, and they make their way into the middle of the dance floor, bouncing up and down to New Order. Later, standing by the bar, he looks on as she climbs the oversize stairs and dances above the crowd. “I never stopped being fascinated by her,” he says. “I like anything that’s larger than life, you know? That’s my gym, my whole life.”

By a quarter to five, the crowd has thinned, and husband and wife decide to call it a night. As they cruise down Fifth Avenue in the back of a taxi, the streets are starting to fill with morning joggers, dog-walkers, garbagemen. She rests her head on her husband’s tectonic pectoral muscle and closes her eyes. “I think tonight was good. Do you, honey?” she asks. “Yeah, babe, it was,” he replies. When they get home, Barton immediately collapses in the bedroom, a dark, crimson-walled cove with an elevated bed surrounded by candelabras and workout equipment. But Susanne can’t fall asleep yet. She never can. She frees her feet from her boots, snacks on some shrimp sushi, and draws a warm bath, her preferred environment for “pondering and marveling at the night.” By the time she’s ready to go to bed, she realizes it’s seven, sunlight is pouring through the windows, and Bailey has to be up for school. Quietly, tiredly, she tiptoes into his room. “Hey, you,” she says, nudging him gently. “Good morning. Time to wake up.”