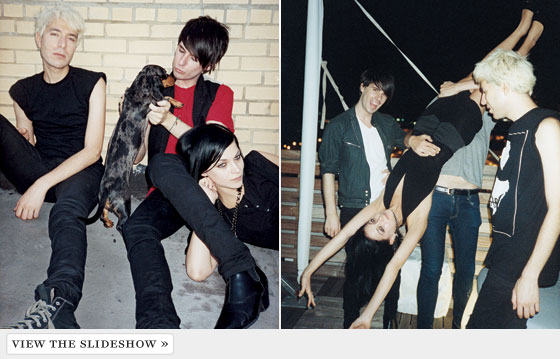

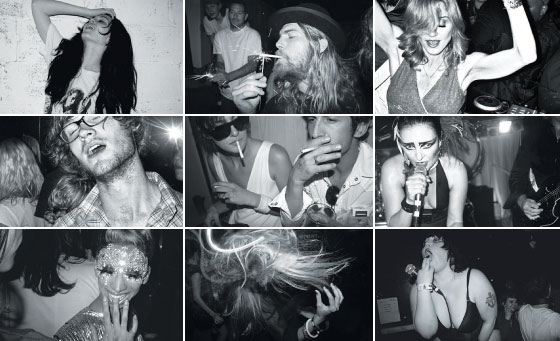

Photographs by Cass Bird

Geordon Nicol is sitting in the backyard of his East Village apartment, hiding out in tight black pants. It’s six weeks before the last night of MisShapes, a downtown Manhattan dance party he started with two friends in 2002, when he was only 19. “None of this was planned,” he declares wearily in his flat, affectless drone, chewing gum tucked into a top molar. Though as it turned out, the MisShapes phenomenon couldn’t have gone better if it had been rolled out by the most talented branding experts in the world.

And in a way, maybe it was: Nicol, the group’s impresario in waist 26 jeans, who is looking less like a vampiric English sheepdog these days, and his partners, Leigh Lezark, also 23, whose beauty recalls Linda Fiorentino by way of Edie Sedgwick, and Greg Krelenstein, 28, whose heavy-lidded gaze reminds you of a cheerful Muppet, were never bedeviled by some outsider notion of selling out. Like many raised on (or possibly by) MySpace, the peddling of a self-created notion of themselves comes naturally. They would of course become insiders, famous in some way, and probably rich.

“We started MisShapes to have fun, because there was nowhere to go,” says Nicol. But now he mostly goes nowhere. He watches Law & Order reruns off his DVR at home instead. “It was the best time in our lives. But as it got bigger and we had to do more, it’s not fun. It’s work.”

Which is why, on September 8, they decided to pull the party’s plug, with a night that also was designed to launch their 228-page photo book, a retrospective look at their five-year climb to becoming increasingly mass-market pop-culture darlings. Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker, legendary punk journalist Legs McNeil, and Vogue fashion-news editor Sally Singer wrote forewords. With friends like this, they aren’t going to go begging for drink tickets even if they’re no longer hosting a dance party.

This summer, they have D.J.-ed with the True Colors tour, which featured Debbie Harry and Cyndi Lauper, and opened for Courtney Love. At the moment, there are elaborate promotional displays of pictures from the book at Henri Bendel here and Colette in Paris. Looking forward, they’re negotiating to get a show on Sirius Satellite Radio (although the contract is not signed), and planning a spring 2008 fashion line for “a global brand” they refuse to name (but that has been reported to be H&M), as well as some remixes and film soundtracking. Nicol has secured advertisers to turn MisShapes.com into an online fashion magazine, with features on people such as their “really good friend” Sienna Miller. That’ll start later this month. But the party’s over.

It all began in the fall of 2001, when an underage Nicol snuck in the side door of Tiswas, a Britpop party. Krelenstein, an NYU senior who was interning at a publicity firm, and Lezark, who’d just moved to town two weeks before, had met that night at the club. Krelenstein spotted Nicol and told him he resembled Conor Oberst of Bright Eyes; Nicol was disgusted. Plus he’d been dating the same guy that a high-school friend of Lezark’s was dating, and so she vengefully attempted to light his eyebrows on fire. In spite of these rocky beginnings, soon enough they became roommates. “We decided all the parties were lame. We were already over it and jaded at 17,” says Lezark.

Lezark jaded early. She grew up in Toms River, New Jersey, daughter of a fiberglass plant manager and a mother who did “crafts.” She was the kind of arty teenager who made her own clothes, eschewed MTV for Full Frontal Fashion, and started going out to Manhattan gay bars—“If it was a weekend, it was a gay bar! Don’t know why!”—and CBGB at age 14, with a fake I.D. made by a girl in her French class. Apparently, her fashion sense was forged early. “I’ve looked the same since I was 16,” she says. “I didn’t say, ‘This is the persona I’m going to put on for the media.’”

After high-school graduation, she moved to the Lower East Side and took photography classes at Hunter College. “I had no idea what I wanted to do when I came here,” she says. “Art, I guess.”

Of the three MisShapes founders, only Krelenstein, who grew up in Marlboro, New Jersey, has a good relationship with his parents, a dentist and a homemaker; they’ve been known to attend some MisShapes events and provide the trio with dental care.

The legend of Geordon Nicol, as described by Geordon Nicol, begins with his birth in suburban Toronto. His father worked for Air Canada; his mother’s an accountant. They divorced when he was 4, leaving him shy and withdrawn (he first dyed his brown hair black at 8); when he was 9, his grandmother enrolled him in acting classes to bring him out of his shell. This led to TV commercials for Nerf toys and Imperial margarine (in which he was dressed as a child Elvis in an all-Elvis family), and small roles in Canadian kiddie shows. But he was unpopular: “I was beaten up every day.” When he was 14, he ran away to Los Angeles to the apartment of an uncle. When he was 16, he dropped out of a professional high school and followed a boyfriend to New York, where they lived on his royalties. They broke up. He got into cocaine, which necessitated a return to Canada in the fall of 2002 to clean up a little. But he was back in New York for that fateful night at Tiswas.

On the first New Year’s eve after they met, the three new friends threw a party in their apartment. They made fliers, filched two cases of vodka from a friend’s father’s restaurant, and filled gift bags with V magazines and condoms from a Harlem AIDS clinic. Three hundred people showed up. “It was insanity,” says Lezark. “Someone joked, ‘You should be doing this for real.’”

So they did: Lezark and Nicol made up a résumé and lied about their ages in order to take over a former lesbian bar on Seventh Avenue South on Saturday night. “When this started, I was hanging out with friends and having fun,” Nicol says. “I was doing a lot of drugs. I had an idea that I could be good at a number of things, but I didn’t know what I was doing.”

MisShapes turned the club, Luke & Leroy (and, later, nearby Don Hill’s), into an exuberant Never Never land, where Wendys were welcome in many shapes and sizes, but the Peters were almost invariably pubescently thin. It quickly became a hit with an asexual crowd of lissome, wired-up kids in complicated vest-and-scarf arrangements.

And, crucially, the celebrities were plentiful, thanks to Krelenstein’s job at Starworks, an agency that serves as a kind of liaison between editors and celebrity publicists, coordinating interviews and cover shoots. Boy George D.J.-ed the second night, the Rapture after that. Though the party flattered itself that it was democratic—the postnerd emo crowd didn’t want to think of itself as snobby—the doorman kept it free of the overfed West 27th Street nightlife contingent.

“We were pioneers of certain media tools,” brags Krelenstein. Inspired by the book We’re Desperate, for which L.A. punk-club attendees were photographed police-lineup style in the eighties, he instructed MisShapes’s house photographer, an intern at V magazine, to take similar photos. “We had the first Website of party pictures that I was aware of,” he says. MisShapes.com gets 10 million hits a month. It launched an entire genre of nightlife-photo blogs, not to mention the book.

“Guest D.J.’s” included Madonna, Chloë Sevigny, Yoko Ono, Cocker, and just about anyone cool who was passing through town with a record or movie to promote. “It was a return to kids dressing up,” says Christopher Bollen, editor of V. “And their pictures were put on the Website as a self-generating way of comparing looks. There wasn’t really that kind of institutionalized checking-each-other-out before.”

The party echoed throughout cyberspace. “People were shooting images all over the world, which is not something that would have happened ten years ago,” says Singer, rhapsodizing about the ubiquity of camera phones. “So kids all over the world could have a moment in that scene. It was virtual reality: It was happening in a tiny club in downtown New York, but it was also happening everywhere.”

And in this way, it became a second life for those who, like Nicol, got beaten up every day. “One 17-year-old kid wrote to me on MySpace,” says Krelenstein, sitting in pajamas in his bedroom—which looks much like a 17-year-old’s, with its messy twin bed, clothes-strewn floor, and pictures of a topless Courtney Love tacked to the wall. “He’s in Seattle, but in his profile, he put location as ‘Not at MisShapes, Seattle.’ What does that mean? I wrote him, and he said, ‘I really wish I could be at MisShapes, and I’m not there.’ And I thought, He’s identifying his whole world around not being at a certain club. That’s what’s most inspiring.” Krelenstein didn’t have that when he was that age. “But kids all over the world can look at our pictures and realize there’s a world apart from where they’re growing up.”

It was also convenient for the hungry merchants of what’s next. A stylist friend at Vogue dressed them for photo shoots. The features editor of Teen Vogue visited the party and wrote about them. Paper did a huge fashion spread on them in fall 2005. The Times Sunday “Styles” section covered them, and that paper’s fashion critic, Cathy Horyn, invited them to go shopping. Singer popped by and became a booster: “They have a great look—the kind that people who work in fashion love,” she says. “Extremely lean, extremely graphic—it photographs well. It’s not grunge.”

“The feeling around the office was that you had a party that combined the celebrity and the semi-celebrity and the Internet celebrity,” says Jon Durbin, a former managing editor of Paper. “At the same time, it was also sort of a focal point for downtown art, fashion, and music.” Their bleak presentation secured them a place in a long tradition of New York’s Great Blanks—think Warhol and Blondie—attractive screens onto which fashion editors could project their fantasies.

“There was something timeless about it,” says Singer. “And yet it’s also timely, because that scene is hard to re-create in a city that doesn’t allow for much small business anymore. It was wonderfully inclusive and not about money.”

Except that soon enough it became clear to the MisShapes troika that this was going to be something big. Which is to say moneymaking. They’re flown all over the world to D.J. at fashion shows and private parties; this provides most of their income (they’ll still be available for special events). They’ve peered through matching curtains of black hair in dozens of fashion spreads. Lezark recently warranted a spread in Vogue, for which she shot the photographs, and is a model in the fall H&M campaign photographed by Terry Richardson. They were turned into a living art installation at a Versace party in Milan.

“We’ve never said we’re the most creative or proficient D.J.’s,” says Krelenstein. “What we’ve done is created an aesthetic people are attracted to.” People like the tastemaker Singer, as well as publicists like Richard Gallegos, who hired them to D.J. at the opening of the Gramercy Starck condo. “It doesn’t hurt that they’re attractive,” he says. “They’re not so edgy that people are intimidated by it. I think there’s an accessibility to their energy and their style.”

MisShapes’s operational base is a four-bedroom duplex in the East Village, decorated in Later Collegiate style: a couch slipcovered with a black sheet, a black plastic DVD rack, a dusty non-flat-screen television. There are two walls of magazines, filed in huge Ikea bookcases. Once when I was there, the ceilings and walls of the top floor were covered with aluminum foil—just like Warhol’s Factory!—a leftover from a Nylon magazine photo shoot. (Nylon’s idea.)

Lezark’s hardly around since she started dating 22-year-old actor Max Minghella, star of Art School Confidential and son of director Anthony. “Leigh is happy at home with her boyfriend,” says Krelenstein, “and Geordon is happy at home with his computer.” These days, Nicol slogs all day behind his MacBook on the new magazine, with the help of their assistant Janelle and the MisShapes intern, a blond, bespectacled 17-year-old named Jackson, who looks like Garth from Wayne’s World.

“I don’t question the professional advantages,” says Nicol, sighing, about what has happened to the three of them. “I’m starting to question the personal side.” MTV and VH1 offered the trio reality shows. Lezark and Krelenstein were in favor; Nicol nixed the idea, fearing he would lose all his friends and not be able to find a boyfriend. People have gone through their garbage; Lezark has been followed home and threatened. Ironically, it’s the Internet, which made the MisShapes, that has bunkered him in his house. “Normal people can go out and meet people at bars. We can’t do that anymore,” says Nicol. “The Internet has made it so that people have so much information about us that they don’t even have to ask us anything: They know it. Or they think we’re assholes, so they won’t talk to us, or they’ll talk about us. Both make a night out really not pleasant.”

This spring, they were flown to Miami to D.J. a private 18th-birthday party. When they toured the boy’s bedroom, they saw that his walls were covered with printouts of every MisShapes party photo that had ever been posted online. The teen had built a cardboard model house and labeled it HOUSE OF JEALOUS LOVERS (after a song by the band the Rapture). It contained pictures of the MisShapes and everyone they had dated and broken up with—information he had found online. “It was really, really bizarre,” says Nicol.

But can the MisShapes fantasy continue without the weekly party? Perhaps they realized that unless they shut the party down, put its coolness behind the velvet rope of instant nostalgia, it would quickly lose its remaining value (already the taunting editors of Gawker.com have attempted to draw a circle of uncoolness around them by labeling them “haute whores”). “When you’re 19 and people like what you’re doing, they want to take photos of you, they want to dress you up, it’s flattering,” says Nicol. “It feeds your ego. But you don’t think about the repercussions: who’s going to be seeing it, where that can lead.”