During the interminable struggle to respond appropriately to 9/11, a slugfest that’s generated vast clouds of political and bureaucratic dust, we’ve had only one blue-sky moment—the unveiling last year of Santiago Calatrava’s luminous transit station at ground zero. The immediate response, even among weary cynics, was something like At last! New York’s finally rising to the challenge. The building not only represented a classical expression of hope (it evoked a bird taking flight) but gloried in the city’s past. It invited comparison to the secular cathedrals of Grand Central and the old Penn Station, and, equally, to the city’s great modernist celebrations of movement, Eero Saarinen’s TWA terminal at Kennedy airport and Pier Luigi Nervi’s bus terminal at the George Washington Bridge. Maybe, just maybe, the bravura new building suggested, civic culture in New York was not moribund. Maybe New York would once again find the energy to dream big. Maybe it would have a 21st century.

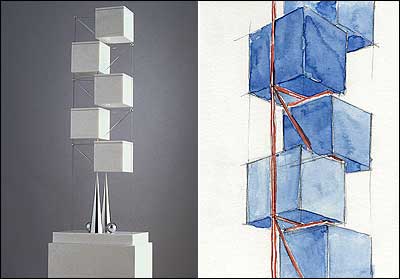

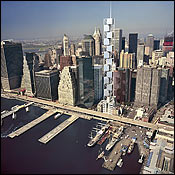

In the same period, Calatrava also proposed building a skyscraper near the Brooklyn Bridge, at South Street. This building was as culturally provocative as his ground-zero station. It seemed to infiltrate and subtly challenge the skyline, which is where New York dreams. Recently, the skyline has been bulking up like an athlete on steroids, the muscular boxes crowding out the slender spires of an earlier era. Calatrava, by contrast, presented New York with a slender, light-as-air building, one composed of twelve stacked cubes that rise like a stairway to heaven. Each cube was a residence, a townhouse afloat in the sky. And each, to be sure, was absurdly expensive. But the idea also seemed otherworldly, magical. He was putting the sky back in the skyline. It was the first New York building in a long while to provoke that peculiar architectural compliment: “What’s that!”

“I’ve always had a dream about New York,” says Calatrava. “New York is an island … those bridges … the skyline … the dynamism … ”

Ah, the old music. It sounds sweet to these ears.

Calatrava is very well known in Europe, where he’s become a symbol-maker for cities that want to jazz up their identity with memorable bridges, airports, railway stations, and cultural institutions. (The construction of Frank Gehry’s museum in Bilbao is the most celebrated contemporary instance of a city using architecture to redefine itself.) In the United States, he’s given Milwaukee a talk piece, creating an addition to its lakeshore art museum that has a dramatic brise-soleil that opens and closes like the wings of a bird. He will build a cathedral in Oakland, and, perhaps, the tallest skyscraper in Chicago. But his eyes are now mainly, and resolutely, focused upon New York. Although he lives in Zurich, maintaining offices there and in his hometown of Valencia, Spain, he has a townhouse in Manhattan, where his wife and three of his children now live. Soon, he’ll move in. “I would like to build a new practice in New York,” he says.

What will Calatrava’s arrival mean for us? To help the city get to know him, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is opening an exhibition next week called “Santiago Calatrava: Sculpture Into Architecture.” It will contain examples of the sculpture and drawing in which Calatrava works out his essential architectural ideas; it will also include models of buildings and work related to his transportation hub at ground zero. Calatrava himself is putting a modest face on his ambitions. “I am 54. I just like it here,” he says. “I am not aspiring. I would just like to contribute with a couple of gestures.” Well, I doubt it. There’s no such thing as a modest architect. Calatrava wants to make a big difference. His English is imperfect, but even so, his passion for the city seems to build as he talks, the words circling and rising. He emphasizes the great artistic challenge of living in New York today—both to bring new-world vitality into the 21st century and to reflect the psychic changes created by the terrorist attack. “September 11 has given the city more depth, making it more profound,” he says. “The city has gained a tragic sense of life. It is now like Athens or Rome or Jerusalem, one of those great cities that has been historically hurt and then rebuilt itself.”

Who in New York talks that way nowadays? Calatrava appears entirely unjaded, a true believer in New York’s past and future. He obviously relishes the challenges facing his adopted city. “You cannot ignore these challenges,” he says. “New York is not a place that lets you be indifferent. New York is this kind of place that, wherever you go, wherever you move, you are always confronted by your own time. New York is the city of the 21st century.” Of course, the skyline entrances Calatrava, who regards it as the city’s most important gift to the world: “The skyline is a great invention.” Even the ugly boxes, as offensive as they are individually, “as a group, lighted up at night, contribute to the mass.” He likens the skyline to a living forest in which the whole is greater than any individual tree. New growth must come into the forest if it is to remain healthy. “You do new things—or you repeat what others have done before you.” Repetition, it seems, leads to sterility.

From the first, Calatrava has looked relentlessly ahead. He was born in Franco’s Spain, a repressive and suffocating environment. Artists like Picasso could maintain the culture of Spain only by moving beyond its borders. Toward the end of Franco’s reign, Calatrava, having earned a degree in architecture, moved to Zurich to study civil engineering. He continues to emphasize inventive structure—and to insist that there’s no necessary difference between engineering and architecture. If Frank Gehry is obsessed with the “skin” of buildings, as many critics suggest, then Calatrava delights in revealing their bones. But he’s nothing like a “form follows function” man; there’s not much residue, in his sensibility, of the puritanical strain of modernism that once rejected ornament and artifice. Calatrava is essentially a baroque artist. He’s theatrical. He loves movement. He uses contemporary engineering to create acrobatic curves to wow an audience. His buildings are often biomorphic in appearance—like those of Saarinen, the fanciful modernist who is one of his heroes—rather than rectilinear. He likes the arc. His signature shape is the wing.

No doubt the claustrophobia of Franco’s Spain has something to do with Calatrava’s appreciation for wings and open air. Over the years, his actual commissions have added to this impression of a man who wants to escape, to keep moving, and to fly. Although Calatrava himself believes that his “transportation” specialty developed largely by happenstance—as a young Spanish architect in Zurich, he could get commissions only by entering architectural competitions for public works—his ongoing delight in such projects suggests a deeper passion. Bridges are especially close to his heart. They offer an escape from earthbound problems. They make connections. They also seamlessly unite engineering and design. Calatrava admires the historical “heroism” of the Brooklyn Bridge, and he considers the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco one of the greatest artistic achievements of the twentieth century. He loves the George Washington Bridge, too: “I like the presence of the pylons, to see all those metal crosses when they are lighted. And also the tremendous slenderness. How daring it was to build a bridge like that at the time!”

Calatrava’s bridges—arguably his best work—are often whimsically asymmetrical. They suggest a smile or a wave of the hand, instead of a trudge across no-man’s-land. His airports and railway stations have an airy quality of uplift. Like Grand Central Terminal, they emphasize light and have a larger-than-life presence, encouraging weary commuters to lift their shoulders. Both his addition in Milwaukee and the cultural center he built in the Canary Islands are extravagantly shaped. Calatrava is one of those architects who think sculpturally: His buildings could almost be giant works of public art. In fact, the power of the computer and the development of new materials now enable architect-engineers like Calatrava to devise heretofore unimaginable shapes for buildings. The Milwaukee addition evokes masts and sails as well as wings. The transportation hub at ground zero was inspired by the thought of a child releasing a bird into the air.

A man of curves in a city of grids, Calatrava could help change our visual culture. But his more important role may simply be to embolden New York.

Calatrava draws constantly, with ease and fluidity. He’s filled up dozens of elegant sketchbooks. He often draws the figure. His proposed tower at South Street derives, ultimately, from drawings he made of bodies twisting back upon themselves; these, in turn, inspired him to create a sculpture that’s an abstracted version of such figures; now the sculpture is evolving into an actual building. No doubt Calatrava will continue to design curvy, biomorphic structures—you can’t really change your handwriting—but he’s also excited about his new, more rectangular style. He’s proud of the building because, he says, it is a new kind of skyscraper: It won’t transform the skyline, but will add something fresh. Some criticize the tower as yet another cultural celebration of wealth, an example of the ostentation that has turned New York into a place of hoggish materialism. (Each of the four-story “townhouses” contains 10,000 square feet of space and is priced between $29 million and $59 million; unless the developer finds buyers, the skyscraper may never be built.) The critics have a point. At the same time, wealth often makes possible the creation of the magically grand or elevated. New York has never lacked for palaces.

If Calatrava gets a number of important commissions—and our pusillanimous pols don’t financially starve his ground-zero station to death—he could help change the visual culture of New York. A man of curves in a city of grids, he could soften some of the city’s hard edges and awaken a more feminine, playful spirit. (He loves the Flatiron Building, with its prowlike curve and strange raked angles.) Calatrava believes that New York needs many more excellent buildings of “intermediate” scale, to help humanize and modulate the powerful effect of so many towers. He’s also an architect who insists upon air and light, which is rarer than you might think. The weight of New York is impressive, of course, but that doesn’t mean architects shouldn’t also think about dematerializing line, floating forms, and bringing more light down from the sky. Perhaps Calatrava’s emphasis upon engineering and technological whiz-bang will also help revive the now moribund tradition of creating brazen engineering marvels. This was always a city of engineers, not just fancy-pants aesthetes.

But Calatrava’s more important role may simply be to embolden New York. Historically, immigrants have often brought with them an air of audacious optimism. They want to believe in the city and remake the world. They can still be romantic. There’s an old-world sweetness about Calatrava’s art—despite its rigorous geometry—that some New Yorkers may find corny. His inspiration for the station at ground zero, that image of a child releasing a bird, is sentimental but also timeless. (It wouldn’t have worried Matisse.) In any case, the city and its billionaires should take more chances with heightened feeling. They need to rediscover the New York of daring and ambition. When I asked Calatrava what he’d build in New York—if he could build anything at all—he said, “I would build a bridge.” Yes, that bridge to the 21st century.

Santiago Calatrava: Sculpture Into Architecture

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

October 18

through March 5.