The hundred-million-dollar barrier for a contemporary-art sale is a thing of the past: Christie’s has bested it two spring seasons in a row. On November 8 and 9, the house can cement its dominance in Contemporary over Sotheby’s, with a sale estimated to bring up to $145 million. The Christie’s auction is stuffed with Abstract Expressionist and postwar masterworks, including the biggest group of Willem de Koonings ever at auction—23 in all, over two days—from the estate of his lawyer, Lee V. Eastman.

Big prizes: One in particular: the huge untitled painting that de Kooning gave Eastman from his 1977 series (Not shown). The painting, which pins Hamptons light and air to the canvas like butterflies, carries a very reasonable estimate of $4 million to $6 million.

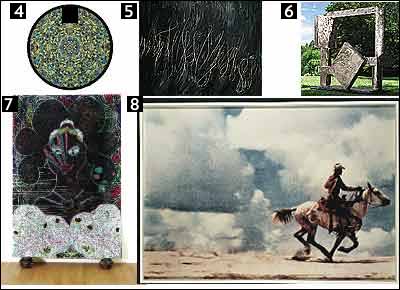

Mark Rothko took a chance and attached a rare title to his big and sunny Homage to Matisse (1953; 2). The notorious depressive liked the result enough that he got married in front of the picture. From the collection of Edward Broida, it has an unpublished estimate of $15 million to $20 million. Francis Bacon’s Study for a Pope I (1961) is the anxious yin to Rothko’s transcendent yang. The $7 million low estimate is not unheard of; a $9 million record for Bacon was set this June in London.

It doesn’t take a crashingly original work to get big prices, either. Three Richard Princes mark the sly thief at the top of his game. One of two prints of Untitled (Cowboy) (1989; 8) is a hefty $900,000 to $1.2 million—but the other is in the Metropolitan Museum.

Likely bargains: A demure Albers Study for Homage to the Square (1960), at $200,000 to $250,000, is priced in line for this series’ choice works. But its provenance is special: Eastman bought it directly from Albers. Richard Tuttle’s mellow lavender wall sculpture Wave (1964–65) is a well-timed buy at $150,000 to $200,000—just before his Whitney retrospective opens.

At this price? Roy Lichtenstein’s film-producer son, Mitchell, is selling one of his father’s works for an undisclosed estimate of $12 million to $16 million. In the Car (1963; 3), a classic tense girl-resists-boy scene, bears a handwritten dedication from Dad to 7-year-old son. The house is betting on pent-up demand for rarely offered sixties paintings—but that price is double the artist’s record of $7.2 million.

Sotheby’s is not ceding the field, though, deploying a cadre of shock troops on November 9 whose legacy is a healthy sense of irony. Four Jeff Koons sculptures, three Prince appropriations, two Damien Hirsts (including The Most Beautiful Thing in the World, 4), two Basquiats, a David Salle, an Eric Fischl, and a Gilbert and George constitute an art-world I Love the 80s episode.

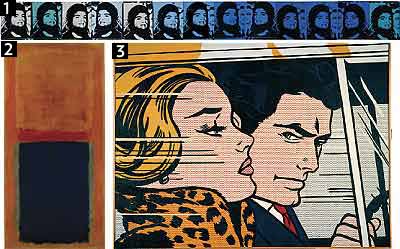

Big prizes: The paterfamilias of pop-culture repackaging, Andy Warhol, leads them all, with his Jackie Frieze (1964; 1), estimated to sell for upwards of $8 million. The repeating silk screen of Jacqueline Kennedy twins glamour with disaster, as it was made from a photo of the veiled, grieving widow at JFK’s funeral. Warhol is becoming something of a house artist: Of the sale’s 54 lots, nine are Andy’s, and his Red Liz was the biggest success of Sotheby’s spring, at $12.6 million.

Some earnest bruisers bring gravitas as well. In Three Studies for Self-Portrait (1976), with a low estimate of $4 million, Francis Bacon comes off like a character in a David Fincher film: battered and proud of it. Cy Twombly’s Untitled (New York City) (1968; 5) is pricey at about $8 million, but it is a pristine and desirable chalkboard painting. Its elegant graffiti finds an unlikely kinship with the hectic scrawls of Basquiat’s El Gran Espectaculo (The History of Black People) (1983), estimated at $4.5 million to $6.5 million.

Likely bargains: The woman in Chris Ofili’s Strange Eyes (2001; 7) wears her glitter well. The oil-and-glitter portrait, set on those infamous dung balls, is estimated to top $800,000. Yes, that nears his auction record of $1 million, but this is a big, flirty, pretty painting, and Ofili has a lot of momentum. The $180,000 estimate for Franz Ackermann’s bright, striped Evasion VXIII (1998) is in line with his recent sales. And Matthew Barney’s Cremaster I: Orchidella photograph (1995) comes in a self-lubricating frame, which alone seems worth the $100,000 to $150,000. It was made in an edition of six, and another just sold for $138,000 in London; a third went for $228,000 at Phillips last spring.

At this price? David Smith’s Humvee-size Cubi XXVIII (1965; 6) is the last in the sculptor’s series of 28 boxy stainless-steel configurations. The $8 million low estimate would double Smith’s auction record—which was set in 1994 for Cubi V, one of just seven that isn’t in a museum.

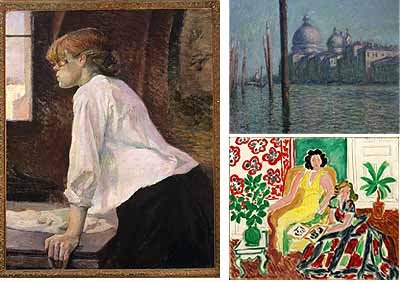

The Year’s Blockbusters

At the Impressionist and Modern auctions, a single big-ticket item can mean the difference between a solid sale and a resounding success. Last fall, Sotheby’s sold Gauguin’s Maternité for $39 million, or 20 percent of its entire auction. Then there was the $104 million Picasso, which accounted for a third of Sotheby’s New York spring 2004 Imp-and-Mod revenues. Christie’s opens the high-stakes sales on November 1, anticipating a buyer for a Toulouse-Lautrec at $20 million to $25 million. If La blanchisseuse (1886–87) makes its estimate, the wistful portrait of a pretty washerwoman trying to get through an honest day’s work would account for around 15 percent of the total, and her iridescent white blouse and coppery hair may prove fetching enough. Without a blockbuster Picasso or Max Beckmann this season, Sotheby’s is spreading the pressure more evenly. Its top lot is a $12 million–to–$16 million Monet, a dusky Venice view called Le Grand Canal (1908), followed by Matisse’s sitting-room fancy of his two favored models, Robe jaune et robe arlequin (Nezy et Lydia), from 1941, for $9 million to $12 million.