In September 1999, Chris Ofili was painting in his studio in London when his fax machine began to whir. “I remember it exactly,” he says. “It was a strange fax, almost like a handmade flyer.” The artifact, forwarded to him by a journalist with whom he’d been corresponding, was being distributed in New York by the Catholic League, in advance of the opening of “Sensation,” a show at the Brooklyn Museum that included a painting by Ofili titled The Holy Virgin Mary.

The painting in question showed a black Madonna with a small dollop of elephant dung affixed to her breast. Perhaps you remember it. It caused something of a stir.

In the following weeks, Ofili’s work would loose a torrent of outrage: angry pickets, sputtering sound bites, even a nut job’s crashing the museum and splashing the portrait with white paint. Most famously, Mayor Giuliani denounced the exhibit as “sick stuff”—he’d not seen it himself, but he’d read about it in a Daily News article under the headline GALLERY OF HORROR—then tried to choke off the Brooklyn Museum’s funding and shut down the show. Subsequent articles described Ofili’s painting as “smeared,” “splattered,” or, in one vivid linguistic curlicue, “festooned” with dung—escalating descriptions that, when distorted in game-of-telephone editorials across the country, made it sound as though Ofili had packed a tennis-ball machine full of wet shit and was firing it at his painting from across the room, while cackling.

In New York, the furor has long since quieted to a quasi-comical echo, but for Ofili it proved hard to block out. “At the time I felt quite vulnerable,” he says. “I didn’t really know what the American rules are. I didn’t know how extreme things could get.”

Ofili’s telling me this on his cell phone, calling from Trinidad. He’d just moved to the island two weeks before, and is still waiting for his possessions to arrive. I ask if it’s a permanent move, or a temporary refuge. “This is my new home,” he says.

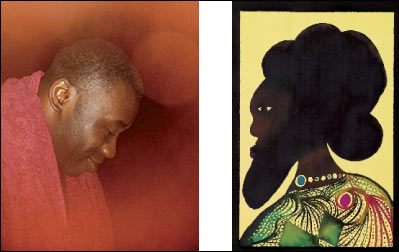

Those who saw Ofili six years ago as a kind of spotlight-crazed charlatan, a Piss Christ Come Lately, might be surprised to find him making his home so far off the art world’s grid. (Born in England to Nigerian parents, he lived in London most of his adult life.) His opponents might also be confounded by his new solo show, titled “Afro Muses,” a collection of colorful, quietly celebratory portraits that opened at the Studio Museum in Harlem last week—his first large exhibit in the city since the “Sensation” ordeal. As a young artist, Ofili was known for his playful, if coprophilic, humor. He once cut off all his dreadlocks, glued them to a pile of dried elephant dung, and called the piece Shithead; an early series of paintings featured a character called Captain Shit, an impressively Afro’d cross between George Clinton, Superman, and Shaft. After “Sensation,” though, his work has become more subdued. “I think that playfulness—it’s not like it’s not there, but it exists in a slightly different way,” he says. “Different things have happened to me in my life, so I try to reflect them.”

Perhaps it’s not so shocking, then, to find that Ofili’s retreated to Trinidad. “I want to be somewhere where I can grow and make changes and not feel scrutinized,” he says. “People here are interested in what you do but they don’t suffocate you. I just feel I’m somewhere where I can exhale.” His close friend, the artist Peter Doig, lives there, and a few years ago invited him for a visit. As it happened, Ofili had been thinking about islands, and journeys, and escapes—thoughts spurred in part by his own life and in part by, of all things, an illustration on a dry-cleaning bag. “It’s a couple looking at each other, with a drawing of a palm tree and a sunset. I quite liked it, and I did a few drawings of it. It was around that time I first came to Trinidad. Two sparks came together, I got a little bit of a flame, and that became the guiding light.”

The light illuminated a new series of paintings shown at the 2003 Venice Biennale, “Within Reach,” for which Ofili once again borrowed religious imagery, this time a black Adam and Eve navigating their way through paradise. “I’ve thought a lot about paradise, and paradise lost,” he says. “In one way, those paintings were a celebration of paradise—a beautiful place where you can relax and be yourself. But they were also about the threats that can exist in paradise: Greed, envy, the poisonous elements, that are always just below the surface.”

Afro Muses

Chris Ofili.

The Studio

Museum in Harlem.

Through July 3.