World War II left Germany in cultural, not just physical, ruins. In contrast to other Western Europeans and Americans, who retained some ongoing belief in institutions, many serious Germans after the war could not hold on to any such faith. History appeared irredeemable, the present absurd. Sundered from their past, German artists were left in a position of nihilistic desperation. Wasn’t art, as traditionally understood, just another fraudulent rhetoric? An elitist diversion? In the early sixties, German artists – inspired mainly by Joseph Beuys – directly confronted this situation. Taking nothing for granted, they edgily challenged the remaining assumptions of their culture. While related to Dada, Fluxus, and Pop, their work was different in spirit. It was darker, more uncomfortable, hectoring. It never seemed to settle into being just art.

“Sigmar Polke: Works on Paper, 1963-1974” is an exhibition of about 180 drawings from an artist who – together with Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, Gerhard Richter, and several others – is an influential figure from this period in German culture. Organized by Margit Rowell for the Museum of Modern Art, the show focuses upon the period when Polke developed his particular angle of vision. From the first, his drawings made a point of avoiding the look of art. They seemed tossed off – often a few throwaway lines done with a ballpoint pen on a scruffy piece of paper. Many presented satirical, cartoonish views of contemporary society. Polke invented a figure he called a “potato-head” who embodies the pedestrian viewpoint of many people in consumer society and a “ghost” who represents the dreamier aspirations of the population. He parodied the historical parade of styles in modernism, mimicking, for example, the strains of lyrical and geometric abstraction.

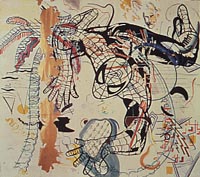

There is no “authority” in Polke’s universe save that of the artist himself, who is not subject to the tainted conventions of history, tradition, and ordinary judgments of good and bad. One result is that his work has a floating, unmoored quality. He does whatever he wants whenever he wants, devising new styles, personas, and methods at will: The tossed-off easily becomes the grandiose. Polke often plays with baroque or grandiloquent aspirations – a reflection in a dark mirror of Nazi utopian rhetoric. In the sixties, he took psychedelic drugs, and much of the art in this exhibit is hallucinatory – a cosmic free-for-all. The centerpiece of the exhibition is a room that contains four mural-size drawings that are together called The Ride on the Eight of Infinity. Patched together from countless smaller drawings, this pastiche reflects a scientific view of the world as a place of ceaseless molecular motion. Its kaleidoscopic narrative line, in turn, comes from motorcyle culture. (Polke actually spattered motorcyle grease across some of the pictures.) The density of the references playing across the surface could nourish a dozen dissertations.

Like many other postwar German artists, Polke brings the pop profusions of the contemporary world into his work – as if to violate the old temples of art. Of course, even art that doesn’t want to look like “art” very soon does. In the handsomely designed catalogue, Rowell makes the interesting argument that Polke is part of the longstanding Rabelaisian tradition in Western culture, subverting elitist norms with a kind of robust, vulgar energy; Breughel is such an artist. But Polke’s art does not, at least to my eye, have the visual strength of a Breughel painting. Instead, he holds interest as a cultural commentator, a kind of writer who writes by other means. A maker of alphabets who doesn’t believe in words.