In one of his best-known drawings, the New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams depicted the night watchman of the American Museum of Natural History shining a flashlight on a dinosaur egg that’s hatching. The cartoon was more than funny; it captured the strange and fanciful secret life of this particular institution. As any New York kid knows, the other-worldly fascination of the museum – the old bones, haunted halls, and beautifully surreal dioramas – is far more vivid than its earnest pedagogical mission. Beneath the academic surface, the museum stimulates romantic dreams of strange places, times, and practices; it serves as both an important teacher and a bizarre wonderland. It was for that reason that this big kid looked forward to its current exhibitions about exotic forms of decorative behavior: “Body Art: Marks of Identity” and “The Butterfly Conservatory: Tropical Butterflies Alive in Winter.” Facts might be gathered, but, just as important, fancy served.

The many imaginative echoes of Body Art seemed especially promising. Today, there are tribes of tattooed New Yorkers with extravagantly colored hair and rings in their noses, eyebrows, ears, navels, tongues. A fresh view of scarification, piercing, and body painting from other eras and regions could create an interesting perspective on our own culture. It could also offer an unusually serious contrast to the contemporary torturing of the flesh recently on display at the “Sensation” show in Brooklyn. Unfortunately, “Body Art” does not live up to its promise. It’s a very timid exhibition with a bland academic tone that never risks offense, and it’s organized around unsurprising truths: Body-art practices link people to their physical and spiritual worlds… . Marks of identity sometimes challenge cultural ideals and sometimes confirm them… . Today’s body art is about experimentation and crossing boundaries… .

The show skirts the visceral and outrageous, avoiding the funkier examples of the subject. The photographs are unfailingly tasteful, even when the subject is a seedy neo-tribal punk from our own culture. There is actually a warning on display from the New York City Department of Health on the dangers of getting a tattoo. You could pass through this exhibition, in short, never supposing that what human beings visit upon their flesh is steeped in fetishism, sexuality, rage, spiritual passion, and Dionysian madness. Maybe that goes on somewhere else, but not in a museum.

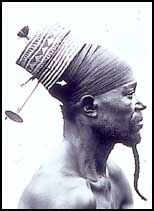

Still, those who like a cracked dinosaur egg will find some extraordinary things in this show. The curators have gathered together more than 600 objects and images, dating from around 3000 B.C. to the present. Not all the cultures represented are well known. For example, the show contains a particularly beautiful collection of black-and-white photographs taken in the twenties of the Selk’nam Indians, a tribe from Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. By wearing astonishing hats and headdresses and covering their naked bodies with bold decorative designs, the Indians transformed themselves into shadowy creatures that seem half-flesh, half-spirit.

The curators have placed examples of body art from both “primitive” and “sophisticated” cultures in close proximity, which effectively emphasizes how useless such distinctions finally become and how similar human preoccupations are across time and place. The line between fashion and ferocity is often very fine; in this show, the grotesque and the delicate constantly intermingle. What could be more savage than the practice – carried out in the elegant precincts of Chinese society – of breaking and binding the feet of little girls? The show contains a beautiful array of the tiny elfin slippers that the girls would wear as adults. Across from these tiny slippers is a case that displays the evolution of the corsets and brassieres that have twisted and shaped the female figure to reflect the ever-changing ideal of what women should look like in Western culture.

The most poignant part of the exhibit is a movie clip that shows what Western society has done to many other cultures where body art was once a serious matter. One section contains some disturbing shots of Western tourists in New Guinea photographing the “natives,” who seem to regard the snapping tourists, in turn, as utterly outlandish. Another demonstrates what happened to the Southeast Nuba people of Sudan after the German photographer Leni Riefenstahl published a lush and pretty book in the seventies full of illustrations of naked young men adorned with painted symbols. A Nuba elder – looking exasperated and bewildered – complained that all Riefenstahl and the tourists following her ever really wanted was “pictures of people without clothes.” Soon, the young men began earning money dolling up their naked bodies for the visiting tourists, with the result that the actual meaning of the body art – along with the traditional position of young men in that society – changed fundamentally. Their painting was now just a performance. The Southeast Nuba became postmodernists.

Of course, the museum’s Butterfly Conservatory – now in its second year – has its earnest academic side. You can learn about pupae and wings. But the concealed meanings are, as usual, more interesting. Traditionally, the museum is the great un-zoo. The birds do not fly; they are stuffed. The butterflies do not flutter; they are mounted. But here they’ve done away with the pins and you can watch real butterflies flutter and hatch within the museum. For once, you can step behind the glass and wander about with the living.

The museum advertises the Conservatory – which sounds elegantly Edwardian – as a magical place filled with tropical plants, butterflies, and the scent of jasmine. But as the name suggests, there could hardly be a more artificial environment. That is what’s finally so entertaining. These particular butterflies are dandies. They live in a small hothouse – filled with plants – that is supposed to simulate a rain forest. (The museum pipes in the sound of howler monkeys, quetzals, and parrots.) They are cultivated on butterfly farms. They have wonderful, theatrical names: Zebra longwings, monarchs, blue morphos. And they do not remind me of whimsy on the wind. They act more like a bunch of cynical actors hanging around backstage smoking and drinking beer. Quite a few are lazily preening and eating rotting fruit. Very occasionally, one does some real work and alights on the head of a little girl. Applause and bows all around. But they mostly prefer to cluster near the bright lights on the ceiling, sipping water spiked with honey, like beautiful barflies.