Every great photograph has a secret. Something mysteriously and tantalizingly withheld, even when the world seems laid out as plainly as a corpse upon a table. The exhibition “Walker Evans,” organized by Jeff L. Rosenheim and opening this week at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, naturally contains many such “secrets” – Evans is a master. In a survey of his work, however, the anticipated mysteries will always have an added power, for Evans is also an iconic artist who gave definitive form to the American story. While wandering among his people, houses, and billboards, you will often have the uncanny sensation of looking past the surface of a society into the secret inner life of America during the first half of the twentieth century.

Evans (1903-1975) is best known for the portraits he made in the thirties of tenant and sharecropper families in Alabama, works published as part of his collaboration with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The pictures soon came to symbolize the dispossessed of America during the Depression; to the politically minded, they exposed the truth behind the patriotic boilerplate. But the images hold our interest because they are not possessed by fiery agitprop or clammy liberal platitudes. They take America behind the customary political stereotypes: No class analysis of social conditions or outcry about poverty could capture the flicker in the face of Allie Mae Burroughs in Evans’s legendary portrait of her. If anything, the series has a quasi-religious, mystical air. A bedroom table in the Burroughs family cabin becomes an American altar. And the children become angels, though not in the cute Norman Rockwell manner. They are gravely ethereal emanations – exciting, challenging, strangely disturbing – from another world.

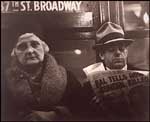

Evans’s other work – too often overlooked because of the fame of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men – also led the eye past the surface of American life. He was a wonderful photographer of regional architecture, but not simply because he was celebrating “an American vernacular.” His houses were as alive as his people, and often as dispossessed. They seem lost in their memories and frequently look pained by time and the twentieth century: troubled by roads and ceaseless changes; made vulnerably quaint. When Evans addressed the “anonymity” of twentieth-century society – another classical theme – he did not make visual speeches about encroaching technology, bland uniformity, or the lonely crowd. He brought an angled anonymity to bear. The subway portraits, street snaps, and photos of penny picture displays are spiky with individuality. And his pictures of public signs and billboards, far from being symbols of capitalist oppression, always seem to be unpeeling into private messages.

Evans is not one of those American artists attracted to nature or the infinite spaces of the West. He would probably have found that subject nostalgic, essentially a lingering dream from the nineteenth century. He insists upon his own time and its man-made environment. A grid has been laid upon the land, and Evans himself instinctively constructs his images from rectangles, boxes, and geometric forms. The almost mathematical precision of his formal compositions establishes an austere modern counterpoint to the many private whispers in his art. Although Evans continued to make good work until the end of his life, he really belongs to the first – not the second – half of “the American century.” His carefully balanced compositions often create an island of stillness, a moment of revelatory quiet amid the modern churnings. In the fifties and sixties, artists greatly influenced by Evans – such as Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander – would shake up the master’s rectangles and rattle his geometries. America would become movement itself. With Evans, there’s still a there there.