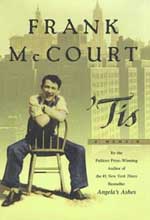

’Tis

By Frank McCourt

Scribner; 367 pages; $26

Frank McCourt is nothing if not lovable, a shaggy chatterbox whose run-on sentences resemble the colorful, crowded laundry lines strung between tenement windows in old photographs. His stories seem clothespinned together, ragged and natural. He’s easy on the ear and always charming; never jarring, strident, pretentious. In Angela’s Ashes, his bestselling memoir of his miserable Irish Catholic childhood, he won, and won over, an audience of millions with his shamrock humanity, his Celtic soul, and emerged as the decade’s beloved official Irishman. It’s a role that comes with certain duties, chief among them to keep the blarney coming until the lights go down.

A sequel to Angela’s Ashes was inevitable, a cultural obligation for McCourt, like buying the house another round of ale and proposing another mournful toast. The book is called ’Tis, and it follows its author’s life (presumably faithfully, but who knows?) from late adolescence to middle age, focusing on his intellectual growth and on his social odyssey as an immigrant. McCourt is again the underdog hero, and hugely lovable – perhaps too lovable. From the moment he gets off the boat in New York, his grassroots heart is assaulted from all sides by snobs and bigots, conformists and poseurs, making the book a long, left-handed tribute to McCourt’s own goodness and vitality.

Again and again, he’s insulted and humiliated, only to dust himself off and muddle on – and though we reflexively root for him at first, a certain empathy fatigue sets in as the slights and injustices pile up. It’s one man against the world in ’Tis, but the fight has too many rounds, all similar, and the hero’s opponent, besides being ugly, only throws low blows.

The siege begins with a drunken priest on the ship from Ireland. He urges the penniless young McCourt to flatter two “rich Protestants from Kentucky” who might be able to offer him a leg up. The epithet becomes a comic tag line, the stiff wealthy Southerners standing for everything that the earthy McCourt can’t stand: humorlessness, arrogance, and greed. McCourt would rather starve than sell his soul, and the book delivers a parade of foils to highlight his rebellious, peasant integrity. McCourt refuses to genuflect to any of them: not the brutal army officer who takes away his weekend pass for refusing to pick up a cigarette butt, not the smooth-talking bank executive who invites him to become a salaryman, not the officious high-school principal who hires him as a teacher. Time and again, McCourt resists the lure of a conventional American life, digressing into chestnut send-ups of tedious cocktail parties, suburban lawns, and stuffy neighborhoods where “all the men wear ties, where some have ties for every day of the week and social functions on top of it.”

What McCourt wants is a literary life, a college education, freedom, love. New York and America are against him, though. He goes to a movie theater to see Hamlet and gets thrown out for eating in the bathroom. He tries to read Dostoyevsky in his rooming house, but his landlady makes him shut his lamp off to save a few pennies on electricity. McCourt exaggerates his youthful bad luck into a kind of cosmic conspiracy: This dreamy, ambitious working man just can’t win. He plays his misadventures for pity and laughs, piling them absurdly high. He’s brilliant on the way that tiny rebuffs and little missteps reinforce each other, combining into disastrous cascades. The power company cuts off your juice, you run an extension cord to a neighbor’s flat, the neighbor grows resentful and pulls the plug, and soon your life is unremitting agony. These are the sort of jokes McCourt excels at: elaborate, anarchic webs of irritating happenstance. The problem is that he can’t make a whole book of them.

Once he’s pulled his best anecdotal stunts, McCourt is obliged to get on with his story – a traditional tale of ambition and self-discovery carried out against the odds. The time is the socially polarized fifties, when, according to the myth, at least, playing jazz was borderline subversive and good-looking quarterback types got all the girls. After being admitted to NYU on the GI Bill, McCourt finds himself fighting both sides of the culture, the longhairs and the football players, too. The longhairs bother him with their empty talk of existential angst, which strikes McCourt as a decadent luxury for spoiled rich kids who don’t know suffering the way poor Irish Catholics know suffering. The jocks enrage him because they’re big and dumb, with perfect white teeth in their handsome bovine heads. These are old, old caricatures – the oldest – but McCourt can’t resist them, and it drags him down, hopelessly dating his tone and even his style, which sounds like derivative, Beat-era polemic: “There’s nothing in my head but Mike Small, blonde, blue-eyed, delicious, sailing through life in her easy Episcopalian way, the all-American girl, with sweet memories of Tiverton in her head, the small town in Rhode Island …”

McCourt, who became a writer late in life after drinking in the same bars as Mailer and Kerouac, is fighting the last war in such lame passages – a war that was won by his fellow rebels back about 1960. “All-American” is his all-purpose curse, and when he writes “porch swing” or “apple pie,” what he means is evil and suburban. Perhaps it’s only fair to let McCourt take his belated potshots at these frayed targets now that he is, finally, up and publishing, but fair is not what literature is about. Mr. Eisenhower, he dead. McCourt is tossing grenades at empty trenches. As for the lampooning of Camus readers, it has an ugly, unattractive edge. It smacks of the same sort of phobic anti-intellectualism that McCourt makes fun of in his book when it happens to come from Catholic nuns and the object of disgust is D. H. Lawrence, say.

When not heaping contempt on all around him for their pomposity and narrow-mindedness, McCourt admires himself for his own large-heartedness. He rhapsodizes sadly about the immigrants turned away by the Ellis Island gatekeepers. He spiritually adopts a shunned old black man as a father figure, despite constant warnings from racist associates to stick to his “own kind.” Befriending oddballs and outcasts at every turn, he never misses the chance to remind us how exceptionally he’s behaving. It’s not so much that he brags of his own virtue; it’s that he fails to acknowledge anyone else’s – except, that is, when the people are scorned by others and only he, McCourt, can see their value. By the end of the memoir, he’s spent his love and most of his lovability. On himself.