A spirited performance of Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini can take the breath away and make a critic hold his tongue, temporarily at least, about any flaws he may have heard or seen. Prior to the Metropolitan’s new, first-ever production, I’d seen the opera just once, back in 1975 when Sarah Caldwell and her Opera Company of Boston staged Cellini with Jon Vickers in the title role. Like most everyone else at the time, I thought that occasion pretty thrilling, and I looked forward to rehearing it on a pair of recently released VAI compact discs. Alas. The breathtaking energy I remembered comes across all right, but Vickers is vocally at sea much of the time, and the more ramshackle parts of the score are hardly disguised.

The Met’s new version, needless to say, is a good deal more polished in all departments, but when the opening-night performance was over, I was still breathing calmly and sorely disappointed. The principal villain is Andrei Serban, whose direction shows a deep distrust of the piece, replacing the opera’s theatrical vigor—Berlioz boldly throws everything in your face, even the worst bits—with endless amounts of irrelevant decoration.

We are never allowed to forget that the action takes place in Rome during carnival time, since dozens of irritating Pierrots constantly caper across the stage, distracting attention from the singers—“Send Out the Clowns” was an old joke before intermission ended. Berlioz clearly identified with the impulsive Cellini, a brilliant sixteenth-century goldsmith, engraver, sculptor, lover, and man of extremes, but having an effete clone of the composer wandering about all evening, jotting down notes with a pen made from a long-stemmed rose, just looked ridiculous. The most effective visual element is George Tsypin’s ingenious set—the sly way it suggests the Colosseum, its stately wraparound staircase for grand entrances and crowd scenes, and the gigantic crucible that explodes to reveal Cellini’s masterpiece, Perseus Killing the Medusa.

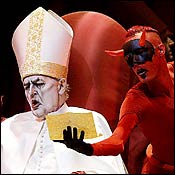

Reconciling the opera’s contradictions, a dashing madcap comedy one moment and a passionately serious melodrama the next, is the director’s main challenge, but Serban is too busy inventing extraneous business to bother with that. It’s more or less up to the singers to find their own way through the opera, and luckily the Met has cast from strength. Marcello Giordani is an immensely appealing Cellini, a poet as well as a man of action, and he sings the music with aristocratic elegance. Every Berlioz tenor needs an easy, ringing upper range, and Giordani always delivers the goods, ardently wooing the papal treasurer’s daughter Teresa (Isabel Bayrakdarian), outwitting a rival sculptor named Fieramosca (Alan Opie), and plotting mischief with his irrepressible apprentice, Ascanio (Kristine Jepson). Robert Lloyd pulls off a tricky bit as Pope Clement VII, one of Berlioz’s most intriguing operatic characters, by managing to be both amusing and clerically imposing in a wheelchair, despite ghoulish makeup and a weird entourage suggesting that he may be the devil himself.

Even with so much vocal talent onstage, the silly production finally defeats them. That’s a pity, since whoever arranged this edition of the opera has chosen judiciously from the various composer-sanctioned versions—even the sequence of events in Act Two now almost makes sense. James Levine conducts with a sure feel for pace and forward motion, although he makes little of the music’s tangy instrumental originality, provides even less dynamic nuance, and never shapes these sometimes strange melodies in ways that might make them sing. Too bad. Perhaps in the end, Berlioz’s problem opera is too unruly to succeed, but I hope one day the Met will try again.