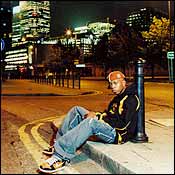

Everything about Dizzee Rascal suggests vulnerability. The British rapper has a strangled yawp of a voice (occasionally he swallows his words whole), his rhymes are all about the rough patches of street life and romance, and his stage name suggests a teetering instability. And unlike his peers across the pond, Dizzee declined to use a real-life violent incident—he was stabbed at the Cyprus resort town Ayia Napa last summer—as a gangsta CV builder, interpreting it instead as a sign of life’s fragility.

Recorded when the emcee (real name Dylan Mills) was just 18, Dizzee’s 2003 debut, Boy in Da Corner, displayed his tremendous vocal gifts, a uniquely unguarded voice. But musically, the record was limited; it was too tied down to the ethos of the scene—“grime,” a dark, DIY version of the dance-music subgenre known as “garage”—that he sprang from. Like other splintered dance subgenres such as drum ’n’ bass, grime emphasizes futuristic sounds over real songs, alienating all but the most obsessive fans.

On Showtime, Dizzee doesn’t give up his sonic adventurousness, but he is a lot more disciplined about it. The production, which he handled himself, is deftly layered. Sounds are introduced slowly and methodically, until they coalesce. Showtime hews to the maxim of the legendary hip-hop producers Bomb Squad that “music is nothing but organized noise.” The track “Face” begins with a hand clap, moves to the metallic ting of a high hat, and then gives way to a low, tunneling bass line; miraculously, the bass line is broken into short spurts and then put back together toward the end.

Set against such sounds are Dizzee’s takes on stardom, which, thankfully, are not about paparazzi or jealous “haters” but rather about the dislocation and surreality of fame. “I’m here I’m everywhere,” Dizzee raps on “Everywhere,” adding, “I can’t be seen.” But he’s not complaining. Showtime is also surprisingly positive about the effects of success (“You can go far if you put your mind to it / You’re a star,” Dizzee counsels on “Dream”), sentiments that could belong to hip-hop’s late-eighties empowerment era. But during a time of profound spiritual ugliness for hip-hop (as embodied in the behind-the-bars Soul on Ice poseur Shyne), Dizzee’s good-naturedness is just as radical as his beats.

About three years ago, Icelandic singer Björk previewed the songs of her then-soon-to-be-released fourth album, Vespertine, in one of the chapels of Harlem’s Riverside Church. The setting suggested grandiosity and pomp, but Björk, pacing the pews in her bare feet and singing mostly without a microphone, gave a performance of striking intimacy. At certain moments, she sang just inches away from fans. The show was transcendently moving; the rapturous love songs of Vespertine brought nearly everyone in the chapel to tears.

“Björk accompanies herself with angelic trills, guttural Gregorian chants, and orgasmic sighs.”

In interviews, Björk has talked about how her frustration with the limitations of musical instruments became the inspiration for her new, entirely a cappella record, Medúlla. But even though Björk has had a longtime passion for choral music, I can’t help but think that the profound emotional directness of the Riverside Church performances in 2001 partly drove the decision to make Medúlla.

On Medúlla, Björk unexpectedly upsets the minimalist a cappella ideal. She sets the big Björk themes—frank sensuality (“Your sweat is salty”), romantic despair (“How am I going to make it right?”), and a kind of feminist self-validation (“Who is it that gave you back your crown?”)—against a river’s rush of sounds (angelic trills, guttural Gregorian chants, orgasmic sighs, percussive beat-boxing). It’s minimalism taken to the max, but, as always with Björk, there’s tremendous emotion behind the high concepts. Especially when heard on headphones, Medúlla is an overwhelming sonic bliss-out, Phil Spector’s wall of sound channeled through the voice box.