We’re just at that moment in previews where everything is going great, but we’re fine-tuning and bringing in new lines and, you know, all that stuff.” Molly Ringwald is talking about her new play, Modern Orthodox, an Off Broadway comedy about a secular Jewish couple who take in an Orthodox diamond merchant. It’s filled with lines (“There is no word for thin in Yiddish!”) that bring down the house, if the house is filled with the Upper West Side. Her voice is a bit raspy; she’s recovering from laryngitis, which she caught from her OB/GYN. “I love my character,” she continues, “she’s smart, sassy, funny … and vulnerable.” The pause is telling—vulnerability was always her trademark.

The last time many of us saw Ringwald was 1986. She was standing next to Duckie (Jon Cryer) at the prom, casting a longing, hurtful glance at Blane (Andrew McCarthy) across the room. It was the final scene of Pretty in Pink, and OMD’s “If You Leave” was playing in the background. At 18, Ringwald was at the peak of her fame, and, in a way, at the end of it. She turned down a role in a subsequent John Hughes movie, Some Kind of Wonderful, and, after a series of unsuccessful projects, decamped to Paris. In her new city, she went native, becoming fluent in French and marrying the novelist Valery Lameignere. But the expatriate dream ended in 2002, with Ringwald filing for divorce, and now she’s back in New York. A vintage celebrity hidden among us.

When asked why she didn’t resettle in Los Angeles, she shoots back, “Have you ever been to L.A.?” and then adds, about this city, “I did my first movie here when I was 13, and I just loved it, and I felt immediately at home.” She owns a fifth-floor walk-up in the East Village. She likes the neighborhood, but when asked to name her favorite spots, she lets out a sarcastic laugh: “So I can be stalked wherever I go?”

It’s difficult to explain, to those who weren’t teenagers in the eighties, just how large Molly Ringwald once loomed in our lives, and why, even now, she must be coy about where she picks up her coffee. For many of us, she was the first real teen we watched at the movies. Graced with what Pauline Kael described as a “charismatic normality,” Ringwald appeared in three films with the writer-director Hughes—Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and Pretty in Pink—that were period-correct fusions of high-school fashion, music, and slang. If you were white and suburban and insecure, you came to the theater and saw yourself.

Ringwald has found work as a book reviewer for the Hartford Courant, and she writes entertainment profiles for the Westchester Journal News. It’s an odd note to her career a bit like Michael Jordan playing golf

Now, almost two decades after her initial fame, Ringwald has become the girl in everyone’s yearbook, the actress we think about when we think about our youth. Which, for her, must be some sort of nightmare. As it turns out, there’s someone near at hand who shares her experience: Jason Biggs, her co-star in Modern Orthodox, is the Molly Ringwald (or perhaps John Cusack) of his generation, having anchored the three American Pie movies. “I tease him mercilessly about everything, American Pie included,” Ringwald says. “But, you know, the funny thing about him is that once you do movies like that, you’re pretty much impossible to embarrass—he’s embarrassed himself before anyone else can, which makes him impervious to all teasing.”

Ringwald could also be talking about herself—this is an actress, after all, whose character was famously felt up by her grandmother—and she recognizes another connection. “It’s a little bit the same thing with him as with me. He started out doing theater and became famous doing film, and when he comes back, everyone’s like, Oooh, a film actor doing stage.”

The stage was Ringwald’s first home, and her childhood sounds like something from the vaudeville era. Born in Sacramento, California, she was the youngest daughter of Bob Ringwald, a blind jazz pianist. Ringwald would belt out classic torch songs, accompanied by her father, and, at age 6, she even released an album called I Wanna Be Loved by You, Molly Sings. Her spin in the Broadway revival of Cabaret was the fulfillment of a long-nurtured ambition, and she hopes to work with Stephen Sondheim someday. And, like many American celebrities, she was on the boards in London recently, playing the part of Sally in a West End production of When Harry Met Sally. Overseas, her career was not up for inspection, but Stateside, some aspects of her Dweezil Zappa–dating days are returning. “Jason and I would go around the corner and get a sandwich,” she says, “and there would be, like, the paparazzi. That rarely happens to me because I’m rarely with anyone who is famous. My partner is not famous, and most of the people we know are not famous.” Ringwald lives with her boyfriend of three years, Panio Gianopoulos, a book editor and a writer. Younger than Ringwald, he published an elegiac essay about dating older women called “Confessions of a Boy Toy” in a recent anthology.

Gianopoulos and Ringwald had a daughter last year, whom they named Mathilda Ereni. At 36, Ringwald is very happy about having become a mother (27 hours of labor), but the five flights with the Maclaren stroller are starting to become a hassle. “I’m thinking about doing Brooklyn,” she says. When the baby was born, the office became the nursery, and the television was jettisoned, for issues of aesthetics and fears of autism. “My best friend growing up was always really defensive about not having a set,” she says, “because everyone was like, Whoa, you don’t have a TV—what’s wrong with you? Every single one of the kids in her family is, like, a doctor or a lawyer.” For those rainy evenings, there are Netflix DVDs, played on her computer: “Panio updates the queue much more often, and then I’ll come in and all of a sudden push the girl movies to the top.”

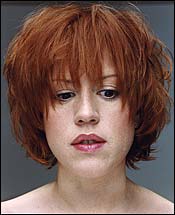

Despite the instant recognition her red hair provides, Ringwald is beginning to blend in, as she cultivates that version of the bohemian New York life that revolves around your apartment, your iPod, your family and friends, and not too much else. “I am sort of comfortable with the amount of fame that I have right now,” she says. “It’s like it’s just enough, you know, and I like that.” In her free moments, she tries to write. Ringwald has plans for a novel, but “it’s not really far enough along yet to, like, even talk about really,” and she resisted the pressure of getting an advance from a publisher. In the meantime, she’s found work as a book reviewer for the Hartford Courant, and she writes entertainment profiles for the Westchester Journal News. Yes, she does. It’s an odd note to her career, a bit like Michael Jordan playing golf. Stephin Merritt, the singer-songwriter of Magnetic Fields, for one, was a bit thrown by sitting across from Ringwald as she set up her tape recorder and notebook. “Excuse me for saying,” he told her, “that I’m surprised you’re doing this at all.”